Video Screen Interfaces As New Sites of Media Circulation Power

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

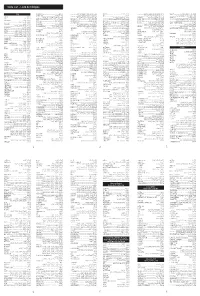

Codelist RT110-1231 V1.5A CL4 20170831 Printing)

Code List – Lista de Códigos , , TV DIGIMATE............................................4301 ..................2271,0141,0581,0871,0921 NAXA.........................................1421,2141 ..................2891,5241,5851,5861,5871 VIZIO..................5631,5611,5561,6121 GEMINI.........................0123,0204,0344 .................0703,0783,1633,1753,0094 TEXSCAN...............................0364 GE(GENERAL ELECTRIC)....2284,0874 .............................1153,2591,2651,0303 GOLDSTAR..............................0432,1181 DIGISTAR..................................0381,0581 ..................2241,6181,2921,3761,4371 NEC.......................................................0001 ..................6051,6061,6071,1631,5551 ..................6131,6111,5651,5621,5711 GENERAL INSTRUMENT (GI)........1034 .................0344,0424,0474,0494,0554 THOMSON..................1834,0803,1753 GOODMIND...........................2284,0874 VENTURER.........................................1164 GRADIENTE.....................[2291 & 0182] ABEX......................................................0401 ..................0871,1061,2451,2471,3901 ..................4721,4761,5051,5061,5181 .............................0341,1221,1431,3451 SANYO...............1161,5261,2891,5251 WARDS.....................................0001,0021 ................................................................1864 .................1064,1084,1094,1104,0092 TIME WARNER......................1254,0824 GRIDLINK................................1144,2254 ZENITH.....................................1173,2571 -

DSTAC WG4 Report August 4, 2015

DSTAC WG4 Report August 4, 2015 REPORT OF WORKING GROUP 4 TO DSTAC Introduction Working Group 4 (WG4) was formed out of the larger DSTAC to address the topic of device platforms, variability, and interfaces. Guidance Description (Part I) The working group will identify existing devices and technologies that receive MVPD and OTT service, such as DVRs, HDTVs, personal computers, tablets in home, connected mobile devices, take- and-go mobile devices, etc., and identify the salient differences important to implementation of the non-security elements of a system to promote the competitive availability of such devices based on downloadable security. (Part II) For each category of existing device identified above, the working group will identify a system comprising minimum standards, protocols, and information other than security elements to enable competitive availability of devices that receive MVPD services. (Part III) The working group may identify alternative systems as appropriate to promote the availability of different categories of navigation devices, consistent with the Commission’s instruction to recommend an approach that would allow consumer electronics manufactures to build devices with competitive interfaces and an approach under which MVPDs would maintain control of the user interface. Product The working group will deliver and present its findings to the full DSTAC. DSTAC WG4 Report August 4, 2015 Table of Contents Part I: Existing Devices and Technologies ............................................................................................... -

Fundamentals of Hard Disk Drives

Digital Storage in Consumer Electronics This page intentionally left blank Digital Storage in Consumer Electronics The Essential Guide Thomas M. Coughlin AMSTERDAM • BOSTON • HEIDELBERG • LONDON NEW YORK • OXFORD • PARIS • SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO • SINGAPORE • SYDNEY • TOKYO Newnes is an imprint of Elsevier Newnes is an imprint of Elsevier 30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA Linacre House, Jordan Hill, Oxford OX2 8DP, UK Copyright © 2008, Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Permissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department in Oxford, UK: phone: (+44) 1865 843830, fax: (+44) 1865 853333, E-mail: [email protected]. You may also complete your request online via the Elsevier homepage (http://elsevier.com), by selecting “Support & Contact” then “Copyright and Permission” and then “Obtaining Permissions.” Recognizing the importance of preserving what has been written, Elsevier prints its books on acid-free paper whenever possible. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coughlin, Thomas M. Digital storage in consumer electronics : the essential guide / Thomas M. Coughlin. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-7506-8465-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Computer storage devices. 2. Household electronics. 3. Digital -

Print Version of the Contents from 1/25/2007

Print version of the contents from www.replaytvupgrade.com 1/25/2007 • Introduction This site was originally started as a source of information on 2 drive ReplayTV upgrades, but now serves as a single source of information for upgrading or repairing a ReplayTV as well as other ReplayTV related information. The most common point of failure in a ReplayTV or ShowStopper is the hard drive and/or software corruption on the hard drive. When that happens the ReplayTV will be stuck in a reboot loop, displaying the first "Please wait ..." screen repeatedly (which is only visible on the composite and s-video outputs) and will be inoperative otherwise. If you only have the coaxial output hooked up to your television, and the ReplayTV is unable to boot, you'll see nothing but static on the TV. See: ReplayTV appears dead (won't boot), nothing on the television . If you're here to replace the hard drive, here's a good place to start: Replacing the hard drive / RTVPatch drive replacement documentation . When the hard drive fails or the software gets corrupted, the ReplayTV will become stuck in a reboot loop, only displaying the "Please Wait ..." screen. (See: ReplayTV stuck at "Please wait..." ). Replacing the drive is relatively easy and can be completed in a short time. Other common problems included poor connections between the power supply and motherboard and/or loose grounding screws on the motherboard and power supply. (See: ReplayTV seems unstable, works for while, then reboots or other strange and/or erratic behavior ). If you're having another problem with a ReplayTV or ShowStopper, there's a lengthy troubleshooting thread with lots of information here: Building a Troubleshooting Checklist . -

Quick Start Guide

XRU300 QUICK START GUIDE UNIVERSAL REMOTE Table of Contents Regulatory Cautions .................................2 Button Descriptions ..................................3 Initial Setup ...............................................5 Battery Insertion ...................................5 Precautionary tips for the battery .........5 Battery Saver .......................................5 Code Saver ..........................................5 Code Setup...............................................6 Setup for TV or other devices ...............6 Using the smart search function ...........7 Smart Learning.......................................... 7 Troubleshooting ........................................9 Warranty. .................................................11 Code List .................................................13 Congratulations on your purchase of VIZIO Universal Remote Control. With this Universal Remote, juggling multiple remote controls is a thing of the past! Your new remote controls up to 8 devices, including the most popular brands of TV, Blu-Ray, DVD, DVR, Cable, and more. Note: Some functions from your original remote may not be controlled by this remote. Use the original remote, if available, to control such functions. Sometimes buttons other than described in these instructions may actually perform the function. For example, the CHAN and VOL buttons might be used to navigate through menu choices. We recommend you experiment with the remote to identify if such situations pertain to your equipment. Your new remote -

QSG XRU110.Pdf

XRU110 DVR/DVD Combos, cont. Home Theater In a Box, cont. PIONEER 0909 0977 CRITERION 0448 POLAROID 1122 DURABRAND 0449 0405 0776 1089 1090 SAMSUNG 1388 EMERSON 0940 SONY 0987 0988 0989 INSIGNIA 1066 TIVO 0912 0909 JVC 0964 TOSHIBA 0983 0973 1114 KLH 0906 KOSS 0415 DVR/SAT Combos LENOXX 0931 LG 0972 1404 BELL 0655 0628 MAGNAVOX 0915 [0969&0756] [0408&0756] BELL EXPRESSVU 0647 0655 MYRON&DAVIS 0962 DIRECTV 1768 1767 1766 1049 NESA 0962 DISH NETWORK 0655 0647 NEXXTECH 1066 1055 0449 DREAMBOX 0620 NORCENT 0928 ECHOSTAR 0655 0647 ONKYO 0975 EXPRESSVU 0647 0655 PANASONIC 0974 FORTEC STAR 0569 0555 0556 0755 1126 [0969&0756] [0966&0756] PHILIPS HUGHES NETWORK 0621 0580 [0408&0757] QUICK NEOSAT 1761 PIONEER [0976&0880] 0968 PANSAT 1035 RADIO SHACK 0449 0919 0920 [0453&0879] PHILIPS 0621 RCA 0449 0920 [0453&0879] START PROSCAN 0653 REGENT 0931 0776 RCA 0653 RIO [0405&0787] GUIDE SAMSUNG 0583 SABA 0919 SONY 0657 0659 SAMSUNG 0454 0942 1099 ULTIMATE TV 0653 0659 SELECTRON 1078 1083 ZENITH 0656 SONY 0986 TECHWOOD 1071 DVR/CABLE Combos TEVION 0448 ZENITH [0405&0787] ADELPHIA 0512 UNIVERSAL AT&T 1753 BELL 1755 CABLEVISION 0512 0506 REMOTE CHARTER 0512 0529 CISICO 0506 0512 COMCAST 0533 0543 COX 0529 ILLICO 0506 0512 MOTOROLA 1754 0533 PIONEER 0506 RCN 0529 ROGERS 0506 0512 SCIENTIFIC ATLANTA 0506 0512 TIME WARNER 0506 0529 0512 VERIZON 0529 0512 VIDEOTRON Home Theater In a Box AIWA [0414&0839] AMW 0918 APEX 0436 BOSE 0672 BOSTON ACOUSTIC 1098 VIZIO CENTRIOS 1067 1055 0449 39 Tesla CLASSIC 1051 Irvine, CA 92618 USA Made in China XRU110-12/11 37 38 Table of Contents Regulatory Cautions Button Description Regulatory Cautions .................................2 FCC Caution INPUT – This button allows the user to cycle Button Descriptions ..................................3 through the available source inputs. -

Interaction Design Principles for Interactive Television

INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR INTERACTIVE TELEVISION A Thesis Presented to The Academic Faculty By Karyn Y. Lu In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Information Design and Technology Georgia Institute of Technology May 2005 INTERACTION DESIGN PRINCIPLES FOR INTERACTIVE TELEVISION Approved by: Dr. Janet H. Murray, Chair School of Literature, Communication, & Culture Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. Peter McGuire School of Literature, Communication, & Culture Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. John Stasko College of Computing Georgia Institute of Technology Allison Dollar Interactive Television Alliance Date Approved: April 13, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without generous support from many people. I am indebted to my thesis and academic advisor, Dr. Janet H. Murray, whose guidance and many insights have been invaluable to me throughout the course of this project as well as in my two years at Georgia Tech. I am also indebted to the members of my committee, professors John Stasko and Peter McGuire, and Allison Dollar from the Interactive Television Alliance, for providing constructive criticism on this document. I am immensely grateful to Allison Dollar, Ben Mendelson, and the entire Interactive Television Alliance for being supportive of this project. Thank you to Nick DeMartino and Anna Marie Piersimoni from the American Film Institute for sharing their thoughts on successful iTV projects and other valuable resources with me. I am grateful to Anna Wichansky and Dale Herigstad for sharing with me the notes from their CHI workshop on designing user interfaces for television as well as other helpful materials. Also, thanks to Brendan Smith for taking time out of his busy schedule to tell me about DVD design. -

DHC-60.7 Basic Manual

DHC-60.7 Basic Manual The Basic Manual includes information needed when starting up and also instructions for frequently used operations. The Advanced Manual has more detailed information and advanced settings. CONTENTS Front Panel ..........................................................................3 Step 2: Initial Setup ............................................. 13 6 Quick Setup menu ..........................................................20 Display .................................................................................4 1 AccuEQ Room Calibration .............................................13 7 Other useful functions ....................................................21 Rear Panel...........................................................................5 2 Source Connection .........................................................14 Troubleshooting .................................................................22 3 Remote Mode Setup ......................................................15 Specifications ....................................................................23 Step 1: Connections .............................................. 6 4 Network Connection .......................................................15 1 Connecting speakers........................................................6 Table of image resolutions .................................................24 ・ Speaker layout ..............................................................6 Step 3: Playing Back .......................................... -

Quick Start Guide Guía De Inicio Rápido

Operating Instructions 65” Class 1080p Plasma HDTV (64.8 inches measured diagonally) Manual de instrucciones Television de alta definición de 1080p y clase 65” de Plasma (64,8 pulgadas medidas diagonalmente) Model No. Número de modelo TH-65PZ750U Quick Start Guide (See page 6) Guía de inicio rápido (vea la página 6) For assistance (U.S.A.), please call: 1-888-VIEW-PTV (843-9788) or visit us at www.panasonic.com/contactinfo For assistance (Puerto Rico), please call: 787-750-4300 or visit us at www.panasonic.com For assistance (Canada), please call: 1-800-561-5505 or visit us at www.panasonic.ca Para solicitar ayuda (EE.UU.), llame al: 1-888-VIEW-PTV (843-9788) ó visítenos en www.panasonic.com/contactinfo Para solicitar ayuda (Puerto Rico), llame al: 787-750-4300 ó visítenos en www.panasonic.com ViVA HD3D Sound Please read these instructions before operating your set and retain them for future reference. English The images shown in this manual are for illustrative purposes only. Español Lea estas instrucciones antes de utilizar su televisor y guárdelas para consultarlas en el futuro. Las imágenes mostradas en este manual tienen solamente fines ilustrativos. TQB2AA0771 Turn your own living room into a movie theater! Experience an amazing level of multimedia excitement ViVA HD3D Sound GalleryPlayer and the GalleryPlayer Manufactured under license from BBE Sound, Inc. SDHC Logo is a trademark. Logo are trademarks of GalleryPlayer, Inc. Licensed by BBE Sound, Inc. under one or more of the HDMI, the HDMI logo and High-Definition “AVCHD” and “AVCHD” logo are following US patents: 5510752, 5736897. -

Cable and Telecommunications Association

THE FUTURE OF VIDEO HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON COMMUNICATIONS AND TECHNOLOGY OF THE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED TWELFTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION JUNE 27, 2012 Serial No. 112–155 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Energy and Commerce energycommerce.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 82–325 PDF WASHINGTON : 2014 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Aug 31 2005 09:46 Mar 14, 2014 Jkt 037690 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 F:\112-15~4\122-15~1 WAYNE COMMITTEE ON ENERGY AND COMMERCE FRED UPTON, Michigan Chairman JOE BARTON, Texas HENRY A. WAXMAN, California Chairman Emeritus Ranking Member CLIFF STEARNS, Florida JOHN D. DINGELL, Michigan ED WHITFIELD, Kentucky Chairman Emeritus JOHN SHIMKUS, Illinois EDWARD J. MARKEY, Massachusetts JOSEPH R. PITTS, Pennsylvania EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York MARY BONO MACK, California FRANK PALLONE, JR., New Jersey GREG WALDEN, Oregon BOBBY L. RUSH, Illinois LEE TERRY, Nebraska ANNA G. ESHOO, California MIKE ROGERS, Michigan ELIOT L. ENGEL, New York SUE WILKINS MYRICK, North Carolina GENE GREEN, Texas Vice Chairman DIANA DEGETTE, Colorado JOHN SULLIVAN, Oklahoma LOIS CAPPS, California TIM MURPHY, Pennsylvania MICHAEL F. DOYLE, Pennsylvania MICHAEL C. BURGESS, Texas JANICE D. SCHAKOWSKY, Illinois MARSHA BLACKBURN, Tennessee CHARLES A. GONZALEZ, Texas BRIAN P. BILBRAY, California TAMMY BALDWIN, Wisconsin CHARLES F. BASS, New Hampshire MIKE ROSS, Arkansas PHIL GINGREY, Georgia JIM MATHESON, Utah STEVE SCALISE, Louisiana G.K.