Ethical Implications of Digital Imaging in Photojournalism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xerox Confidentcolor Technology Putting Exacting Control in Your Hands

Xerox FreeFlow® The future-thinking Print Server ConfidentColor Technology print server. Brochure It anticipates your needs. With the FreeFlow Print Server, you’re positioned to not only better meet your customers’ demands today, but to accommodate whatever applications you need to print tomorrow. Add promotional messages to transactional documents. Consolidate your data center and print shop. Expand your color-critical applications. Move files around the world. It’s an investment that allows you to evolve and grow. PDF/X support for graphic arts Color management for applications. transactional applications. With one button, the FreeFlow Print Server If you’re a transactional printer, this is the assures that a PDF/X file runs as intended. So print server for you. It supports color profiles when a customer embeds color-management in an IPDS data stream with AFP Color settings in a file using Adobe® publishing Management—so you can print color with applications, you can run that file with less time confidence. Images and other content can be in prepress and with consistent color. Files can incorporated from a variety of sources and reliably be sent to multiple locations and multiple appropriately rendered for accurate results. And printers with predictable results. when you’re ready to expand into TransPromo applications, it’s ready, too. Xerox ConfidentColor Technology Find out more Putting exacting control To learn more about the FreeFlow Print Server and ConfidentColor Technology, contact your Xerox sales representative or call 1-800-ASK-XEROX. Or visit us online at www.xerox.com/freeflow. in your hands. © 2009 Xerox Corporation. All rights reserved. -

The Perceived Credibility of Professional Photojournalism Compared to User-Generated Content Among American News Media Audiences

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE August 2020 THE PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY OF PROFESSIONAL PHOTOJOURNALISM COMPARED TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT AMONG AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA AUDIENCES Gina Gayle Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Gayle, Gina, "THE PERCEIVED CREDIBILITY OF PROFESSIONAL PHOTOJOURNALISM COMPARED TO USER-GENERATED CONTENT AMONG AMERICAN NEWS MEDIA AUDIENCES" (2020). Dissertations - ALL. 1212. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/1212 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT This study examines the perceived credibility of professional photojournalism in context to the usage of User-Generated Content (UGC) when compared across digital news and social media platforms, by individual news consumers in the United States employing a Q methodology experiment. The literature review studies source credibility as the theoretical framework through which to begin; however, using an inductive design, the data may indicate additional patterns and themes. Credibility as a news concept has been studied in terms of print media, broadcast and cable television, social media, and inline news, both individually and between genres. Very few studies involve audience perceptions of credibility, and even fewer are concerned with visual images. Using online Q methodology software, this experiment was given to 100 random participants who sorted a total of 40 images labeled with photographer and platform information. The data revealed that audiences do discern the source of the image, in both the platform and the photographer, but also take into consideration the category of news image in their perception of the credibility of an image. -

Deconstructing the Editorial and Production Workflow

Deconstructing the Editorial and Production Workflow Bill Kasdorf Vice President, Apex Content Solutions General Editor, The Columbia Guide to Digital Publishing Metadata Subgroup Lead, EPUB 3.0 & 3.0.1 WG Chair, BISG Content Structure Committee We all know what the stages of the editorial and production workflow are. Design. Copyediting. Typesetting. Artwork. Indexing. Quality Control. Ebook Creation. Ummm. They’re usually done in silos. Which are hard to see into, and are starting to break down. Thinking of these stages in the traditional way leads to suboptimization. In today’s digital ecosystem we need to deconstruct them in order to optimize: Who does what? At what stage(s) of the workflow? How to best manage the process? Who Does What? Do it in-house? Outsource it? Automate it? You can’t answer these questions properly without deconstructing the categories. And the answers differ from publisher to publisher. At What Stage(s) of the Workflow? How do these aspects intersect? How do you avoid duplication and rework? How do you get out of “loopy QC”? Getting the right things right upstream eliminates a lot of headaches downstream. How Best to Manage the Process? Balancing predictability and creativity: where to be strict, and where to be flexible? How can systems and standards help? Buy vs. build vs. wing it? Your systems, partners, and processes should make it easy for you to do the right work and keep you from doing the wrong work. Let’s deconstruct two key workflow stages to see what options there are for optimizing them. Copyediting -

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future

Ethics in Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak S.B. Comparative Media Studies & Electrical Engineering/Computer Science Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2003 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER, 2006 Copyright 2006 Daniel R. Bersak, All Rights Reserved The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________ Department of Comparative Media Studies, August 11, 2006 Certified By: ___________________________________________________________ Edward Barrett Senior Lecturer, Department of Writing Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: __________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Director Ethics In Photojournalism: Past, Present, and Future By Daniel R. Bersak Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies, School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences on August 11, 2006, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract Like writers and editors, photojournalists are held to a standard of ethics. Each publication has a set of rules, sometimes written, sometimes unwritten, that governs what that publication considers to be a truthful and faithful representation of images to the public. These rules cover a wide range of topics such as how a photographer should act while taking pictures, what he or she can and can’t photograph, and whether and how an image can be altered in the darkroom or on the computer. -

Photojournalism Photojournalism

Photojournalism For this section, we'll be looking at photojournalism's impact on shaping people's opinions of the news & world events. Photojournalism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Photojournalism is a particular form of journalism (the collecting, editing, and presenting of news material for publication or broadcast) that employs images in order to tell a news story. It is now usually understood to refer only to still images, but in some cases the term also refers to video used in broadcast journalism. Photojournalism is distinguished from other close branches of photography (e.g., documentary photography, social documentary photography, street photography or celebrity photography) by complying with a rigid ethical framework which demands that the work be both honest and impartial whilst telling the story in strictly journalistic terms. Photojournalists create pictures that contribute to the news media, and help communities connect with one other. Photojournalists must be well informed and knowledgeable about events happening right outside their door. They deliver news in a creative format that is not only informative, but also entertaining. Timeliness The images have meaning in the context of a recently published record of events. Objectivity The situation implied by the images is a fair and accurate representation of the events they depict in both content and tone. Narrative The images combine with other news elements to make facts relatable to audiences. Like a writer, a photojournalist is a reporter, but he or she must often make decisions instantly and carry photographic equipment, often while exposed to significant obstacles (e.g., physical danger, weather, crowds, physical access). -

The General Idea Behind Editing in Narrative Film Is the Coordination of One Shot with Another in Order to Create a Coherent, Artistically Pleasing, Meaningful Whole

Chapter 4: Editing Film 125: The Textbook © Lynne Lerych The general idea behind editing in narrative film is the coordination of one shot with another in order to create a coherent, artistically pleasing, meaningful whole. The system of editing employed in narrative film is called continuity editing – its purpose is to create and provide efficient, functional transitions. Sounds simple enough, right?1 Yeah, no. It’s not really that simple. These three desired qualities of narrative film editing – coherence, artistry, and meaning – are not easy to achieve, especially when you consider what the film editor begins with. The typical shooting phase of a typical two-hour narrative feature film lasts about eight weeks. During that time, the cinematography team may record anywhere from 20 or 30 hours of film on the relatively low end – up to the 240 hours of film that James Cameron and his cinematographer, Russell Carpenter, shot for Titanic – which eventually weighed in at 3 hours and 14 minutes by the time it reached theatres. Most filmmakers will shoot somewhere in between these extremes. No matter how you look at it, though, the editor knows from the outset that in all likelihood less than ten percent of the film shot will make its way into the final product. As if the sheer weight of the available footage weren’t enough, there is the reality that most scenes in feature films are shot out of sequence – in other words, they are typically shot in neither the chronological order of the story nor the temporal order of the film. -

Valuing Subjectivity in Journalism: Bias, Emotions, and Self-Interest As Tools in Arts Reporting

Original Article Journalism Valuing subjectivity in journalism: Bias, emotions, and self-interest as tools in arts reporting Phillipa Chong McMaster University, Canada Abstract This article examines the meanings and norms surrounding subjectivity across traditional and new forms of cultural journalism. While the ideal of objectivity is key to American journalism and its development as a profession, recent scholarship and new media developments have challenged the dominance of objectivity as a professional norm. This article begins with the understanding that subjectivity is an intractable part of knowing (and reporting on) the world around us to build our understanding of different modes of subjectivity and how these animate journalistic practices. Taking arts reporting, specifically reviewing, as a case study, the analysis draws on interviews with 40 book reviewers who write for major American newspapers, including The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, The Washington Post, and prominent blogs. Findings reveal how emotions, bias, and self-interest are salient – sometimes as vice and sometimes as virtue – across the workflow of critics writing for traditional print outlets and book blogs and that these differences can be conceptualized as different epistemic styles. Keywords Blogs, emotion, literary journalism, newspapers, online media, practice, subjectivity/ objectivity Introduction Objectivity has long been the gold standard in American journalism and was key to its development into a profession (Benson and Neveu, 2005; Schudson, 1976). Yet Corresponding author: Phillipa Chong, Department of Sociology, McMaster University, 609 Kenneth Taylor Hall, 1280 Main Street West, Hamilton, ON L8S 4M4, Canada. Email: [email protected] Chong 2 scholars have complicated the picture by pointing to the unattainability of objectivity as an ideal with some noting the increasing acceptance of subjectivity across different forms of journalism (Tumber and Prentoulis, 2003; Wahl-Jorgensen, 2012, 2013; Zelizer, 2009b). -

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020 Nic Newman with Richard Fletcher, Anne Schulz, Simge Andı, and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Supported by Surveyed by © Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism / Digital News Report 2020 4 Contents Foreword by Rasmus Kleis Nielsen 5 3.15 Netherlands 76 Methodology 6 3.16 Norway 77 Authorship and Research Acknowledgements 7 3.17 Poland 78 3.18 Portugal 79 SECTION 1 3.19 Romania 80 Executive Summary and Key Findings by Nic Newman 9 3.20 Slovakia 81 3.21 Spain 82 SECTION 2 3.22 Sweden 83 Further Analysis and International Comparison 33 3.23 Switzerland 84 2.1 How and Why People are Paying for Online News 34 3.24 Turkey 85 2.2 The Resurgence and Importance of Email Newsletters 38 AMERICAS 2.3 How Do People Want the Media to Cover Politics? 42 3.25 United States 88 2.4 Global Turmoil in the Neighbourhood: 3.26 Argentina 89 Problems Mount for Regional and Local News 47 3.27 Brazil 90 2.5 How People Access News about Climate Change 52 3.28 Canada 91 3.29 Chile 92 SECTION 3 3.30 Mexico 93 Country and Market Data 59 ASIA PACIFIC EUROPE 3.31 Australia 96 3.01 United Kingdom 62 3.32 Hong Kong 97 3.02 Austria 63 3.33 Japan 98 3.03 Belgium 64 3.34 Malaysia 99 3.04 Bulgaria 65 3.35 Philippines 100 3.05 Croatia 66 3.36 Singapore 101 3.06 Czech Republic 67 3.37 South Korea 102 3.07 Denmark 68 3.38 Taiwan 103 3.08 Finland 69 AFRICA 3.09 France 70 3.39 Kenya 106 3.10 Germany 71 3.40 South Africa 107 3.11 Greece 72 3.12 Hungary 73 SECTION 4 3.13 Ireland 74 References and Selected Publications 109 3.14 Italy 75 4 / 5 Foreword Professor Rasmus Kleis Nielsen Director, Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (RISJ) The coronavirus crisis is having a profound impact not just on Our main survey this year covered respondents in 40 markets, our health and our communities, but also on the news media. -

151 Australasian Journal of Information Systems Volume 13 Number 2 May 2006

AN EXPLORATION OF USER INTERFACE DESIGNS FOR REAL-TIME PANORAMIC PHOTOGRAPHY Patrick Baudisch, Desney Tan, Drew Steedly, Eric Rudolph, Matt Uyttendaele, Chris Pal, and Richard Szeliski Microsoft Research One Microsoft Way Redmond, WA 98052, USA Email: {baudisch, desney, steedly, erudolph, mattu, szeliski}@ microsoft.com pal@ cs.umass.edu ABSTRACT Image stitching allows users to combine multiple regular-sized photographs into a single wide-angle picture, often referred to as a panoramic picture. To create such a panoramic picture, users traditionally first take all the photographs, then upload them to a PC and stitch. During stitching, however, users often discover that the produced panorama contains artifacts or is incomplete. Fixing these flaws requires retaking individual images, which is often difficult by this time. In this paper, we present Panoramic Viewfinder, an interactive system for panorama construction that offers a real-time preview of the panorama while shooting. As the user swipes the camera across the scene, each photo is immediately added to the preview. By making ghosting and stitching failures apparent, the system allows users to immediately retake necessary images. The system also provides a preview of the cropped panorama. When this preview includes all desired scene elements, users know that the panorama will be complete. Unlike earlier work in the field of real-time stitching, this paper focuses on the user interface aspects of real-time stitching. We describe our prototype, individual shooting modes, and provide an overview of our implementation. Building on our experiences with Panoramic Viewfinder, we discuss a separate design that relaxes the level of synchrony between user and camera required by the current system and provide usage flexibility that we believe might further improve the user experience. -

Telling Stories to a Different Beat: Photojournalism As a “Way of Life”

Bond University DOCTORAL THESIS Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Busst, Naomi Award date: 2012 Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Telling stories to a different beat: Photojournalism as a “Way of Life” Naomi Verity Busst, BPhoto, MJ A thesis submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Media and Communication Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Bond University February 2012 Abstract This thesis presents a grounded theory of how photojournalism is a way of life. Some photojournalists dedicate themselves to telling other people's stories, documenting history and finding alternative ways to disseminate their work to audiences. Many self-fund their projects, not just for the love of the tradition, but also because they feel a sense of responsibility to tell stories that are at times outside the mainstream media’s focus. Some do this through necessity. While most photojournalism research has focused on photographers who are employed by media organisations, little, if any, has been undertaken concerning photojournalists who are freelancers. -

Panorama Photography by Andrew Mcdonald

Panorama Photography by Andrew McDonald Crater Lake - Andrew McDonald (10520 x 3736 - 39.3MP) What is a Panorama? A panorama is any wide-angle view or representation of a physical space, whether in painting, drawing, photography, film/video, or a three-dimensional model. Downtown Kansas City, MO – Andrew McDonald (16614 x 4195 - 69.6MP) How do I make a panorama? Cropping of normal image (4256 x 2832 - 12.0MP) Union Pacific 3985-Andrew McDonald (4256 x 1583 - 6.7MP) • Some Cameras have had this built in • APS Cameras had a setting that would indicate to the printer that the image should be printed as a panorama and would mask the screen off. Some 35mm P&S cameras would show a mask to help with composition. • Advantages • No special equipment or technique required • Best (only?) option for scenes with lots of movement • Disadvantages • Reduction in resolution since you are cutting away portions of the image • Depending on resolution may only be adequate for web or smaller prints How do I make a panorama? Multiple Image Stitching + + = • Digital cameras do this automatically or assist Snake River Overlook – Andrew McDonald (7086 x 2833 - 20.0MP) • Some newer cameras do this by “sweeping the camera” across the scene while holding the shutter button. Images are stitched in-camera. • Other cameras show the left or right edge of prior image to help with composition of next image. Stitching may be done in-camera or multiple images are created. • Advantages • Resolution can be very high by using telephoto lenses to take smaller slices of the scene -

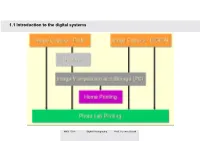

1.1 Introduction to the Digital Systems

1.1 Introduction to the digital systems PHO 130 F Digital Photography Prof. Lorenzo Guasti How a DSLR work and why we call a camera “reflex” The heart of all digital cameras is of course the digital imaging sensor. It is the component that converts the light coming from the subject you are photographing into an electronic signal, and ultimately into the digital photograph that you can view or print PHO 130 F Digital Photography Prof. Lorenzo Guasti Although they all perform the same task and operate in broadly the same way, there are in fact th- ree different types of sensor in common use today. The first one is the CCD, or Charge Coupled Device. CCDs have been around since the 1960s, and have become very advanced, however they can be slower to operate than other types of sensor. The main alternative to CCD is the CMOS, or Complimentary Metal-Oxide Semiconductor sen- sor. The main proponent of this technology being Canon, which uses it in its EOS range of digital SLR cameras. CMOS sensors have some of the signal processing transistors mounted alongside the sensor cell, so they operate more quickly and can be cheaper to make. A third but less common type of sensor is the revolutionary Foveon X3, which offers a number of advantages over conventional sensors but is so far only found in Sigma’s range of digital SLRs and its forthcoming DP1 compact camera. I’ll explain the X3 sensor after I’ve explained how the other two types work. PHO 130 F Digital Photography Prof.