Myths Dispelled: a Historical Account of Diversity and Inclusion at Hbcus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DSU Music Newsletter

Delaware State University Music Department Spring 2018 Music Department Schedule Tues., Mar. 20, 11am: Music Performance Seminar (Theater) Volume 2: Issue 1 Fall 2018 Tues., Mar. 27, 11am: Music Performance Seminar (Theater) Concert choir to perform with Philadelphia orchestra Friday, April 6, 7:00 PM: Junior Recital; Devin Davis, Tenor, Anyre’ Frazier, Alto, On March 28, 29, and 30 of 2019, Tommia Proctor, Soprano (Dover Presbyterian Church) the Delaware State University Concert Choir under the direction of Saturday, April 7, 5:00 PM: Senior Capstone Recital; William Wicks, Tenor (Dover Presbyterian Church) Dr. Lloyd Mallory, Jr. will once again be joining the Philadelphia Sunday, April 8, 4:00 PM: Orchestra. The choir will be Senior Capstone Recital; Michele Justice, Soprano (Dover Presbyterian Church) performing the world premiere of Healing Tones, by the Orchestra’s Tuesday, April 10, 11:00 AM: Percussion Studio Performance Seminar (EH Theater) composer-in-residence Hannibal Lokumbe. In November of 2015 the Sunday, April 15, 4:00 PM: Delaware State University Choir Senior Capstone Recital; Marquita Richardson, Soprano (Dover Presbyterian Church) joined the Philadelphia Orchestra to Tuesday, April 17, 11:00 AM: DSU – A place where dreams begin perform the world premiere of Guest Speaker, Dr. Adrian Barnes, Rowan University (Music Hannibal’s One Land, One River, One Education/Bands) (EH 138) People. About the performance, the Friday, April 20, 12:30 PM: Philadelphia Inquirer said “The massed voices of the Delaware State University Choir, the Lincoln Honors Day, Honors Recital (EH Theater) University Concert Choir, and Morgan State University Choir sang with spirit, accuracy and, near- Friday, April 20, 7:00 PM: More inside! Pg. -

About the Expertise Guide

About the Expertise Guide Hampton University believes it is important to return something to the community of which it is a part. The Expertise Guide provides a vehicle for sharing our resources. Through this guide, Hampton University faculty and staff are available to speak to schools, organizations, community groups, businesses and the media. To request a speaker, choose your topic and speaker. At the right of each name is a designation that indicates which of the activities the expert has agreed to participate in: (MI) media interviews or (PS) free public speaking. For public speaking requests, please fill out the form and email or fax it to the Office of University Relations at least three weeks before the event. For media interviews, please call the Office of University Relations at (757) 727- 5253 or email on of the PR managers and an interview will be arranged as soon as possible. Contact Us: Yuri Rodgers Milligan Director of University Relations beat: breaking news, university administration, special events, policies and procedures [email protected] Matthew White Social Media Manager beat: sciences, engineering, technology, business [email protected] Leha Byrd Communications Manager beat: health, nursing, pharmacy, student and alumni news [email protected] Gianina Thompson Publication Manager beat: liberal arts, social sciences, continuing education, journalism, honors college, leadership institute [email protected] Hampton University Facts Address: Hampton, VA 23668 Founded: 1868 President: -

PRIDE 2020 the Strategic Plan Fordelaware State University PRIDE 2020: Personal Responsibility in Delivering Excellence

PRIDE 2020 The Strategic Plan for Delaware State University PRIDE 2020: Personal Responsibility in Delivering Excellence Statement from the President It is with tremendous pride and pleasure that I present to you the Strategic Plan for Delaware State University – Personal Responsibility in Delivering Excellence – or PRIDE 2020. Delaware State University is a public, comprehensive 1890 land-grant university established by the Delaware General Assembly on May 15, 1891. In these 123 years, DSU has gone from being a State College offering five courses of study in agriculture, chemistry, the classics, engineering and science to a University offering its 4,505 students 52 baccalaureate, 25 master’s and five doctoral degree programs through 21 academic departments. The University has an Honors Program and a number of strategic international partnerships. In addition to its 356-acre main campus with 50 buildings, DSU also has two farm properties, locations in Wilmington and Georgetown, and a fleet of planes for the Aviation Program with a base of operations at the Delaware Air Park in Cheswold. It has been quite a journey from our humble beginnings. DSU has made significant strides along the way to the year 2014. But that was then, and this is now. PRIDE 2020 outlines for you the steps we will collectively take as we begin our journey toward the next decade – a journey that insures we are a University that prepares tomorrow’s leaders, invests in the community’s well-being and meets global challenges. I charged the University Strategic Planning Council with delivering a plan that was comprehensive, challenging and concise. -

Vita Gail Fulgham.2014

NAME: GAIL G. FULGHAM P.O. Box 17760 ADDRESS: 59181400 JRFontaine Lynch Street Park Drive Jackson,Jackson, MS, MS 39217 39206 (601) 979-2617/[email protected] RANK/TITLE: Professor of Economics APPOINTMENT DATE AT JACKSON STATE UNIVERSITY: August 1989 EDUCATION Ph.D. Economics, Howard University, Washington, D.C., 1989 M.A. Economics, Howard University, Washington, D.C., 1984 B.A. Economics, Alcorn State University (Magnum Cum Laude), Lorman, MS, 1981 COURSES TAUGHT AT JACKSON STATE UNIVERSITY (2005-present) Course Number Course Title ECO 211 Macroeconomics ECO 212 Microeconomics ECO 311 Intermediate Macroeconmics ECO 312 Intermediate Microeconomics ECO 359 Business Statistics ECO 446 Urban Economics ECO 470 Economics Seminar for Seniors ECO 511 Macroeconomics -MBA ECO 512 Microeconomics - MBA FNGB 561 Seminar: Business Research Project-MBA ECO-661 Seminar in Business Research Project (on-line) ECO 711 Advanced Macroeconomics-Ph.D. ECO 712 Advanced Microeconomics-Ph.D. ECO 730 Methods in Urban Economics - Ph.D. ECO 735 Seminar in Economics of Housing and Urban Transportation-Ph.D. ECO 760 Econometrics -Ph.D. ECO761 Advanced Econometrics - Ph.D. ECO 799 Ph.D. Dissertation Research in Economics TEACHING AND OTHER PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Professor of Economics (1998 - present); Associate Professor (1993 -1998); Assistant Professor (1989 -1993), Department of Economics, Finance and General Business, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS. Teach several courses in the undergraduate, MBA and Ph.D. programs in the College of Business. Editor, Business and Economic Review, a national journal published by the College of Business. Editor, Journal of Social and Behavioral Science, a national journal published by the Association of Social and Behavioral Scientists. -

The Tuskegee University Libraries Connection Employee Spotlight: Mrs

Ford Motor Company Library The Tuskegee University Architecture Library Engineering Library Libraries Connection Veterinary Medical Library www.tuskegee.edu/libraries Legacy Museum September/October 2010 Volume 3, Issue 1 University Archives University Archives: Winning Awards and Inside this issue: Providing Increased Access Legacy Museum 2 News Tuskegee University on the University Archives Archives has also been Repository. The Interlibrary 2 nominated for the _______________________ Loan (ILL) Process State/Local Records After a 40 year stint at the News from Circula- Commission Annual University of New Mexico 2 tion/Reserves Award in Archival Meteoritic Museum, the Preservation and/or George Washington Carver Employee Spotlight 3 Records Management, Meteorite returns to the Tus- which will be awarded kegee University Campus. Students in Action 3 on November 1, 2010. Although just a slice (22 New Faces 3 pounds) of the original mete- Matt Walker, senior student employee, orite, the meteorite repre- Book Club 4 stands at the Archives table at the sents a rare type and has Academic and Student Support Fair. Recommendations been researched by many Congratulations to Dana ________________________ around the world. The GovDocs Spot 4 Chandler and the Archives Finally, we are live!!! The staff for winning second Archives website Industry Notes 4 place at the 3rd Annual Aca- is now up and Directory 5 demic and Student Support running. Repre- Fair held on August 19, 2010 senting one year in the Daniel Chappie James of preparation EDITOR Center. The theme for the and over 500 Academic and Student Sup- items uploaded, Leigh A. Jones port Fair was entitled, "A the website will Pathway to Achieving Aca- aid patrons Government Documents/ demic Excellence (PAAE)." throughout the Reference Librarian The Archives staff partici- world. -

Rosemary Theriot

R. Theriot 330 10th Ave. N. Suite D-400 Avon Williams Campus Nashville, TN 37203 (615) 963-7367 (work) (615) 963-7011 (fax) [email protected] WORK EXPERIENCE 2011-Present Professor/ Chair of Public Health, Health Administration and Health Sciences Department in the College of Health Sciences at Tennessee State University in Nashville, Tennessee. Duties: Supervise 10 faculty and 2 staff; assign, prepare and approve faculty workloads; oversee two department budgets; prepare various departmental reports; prepare the department self-study report for accreditation; serve on several university and community committees; chair three faculty search committees; recruit students; assisted with the development of the MPH/Ph.D. proposals in Public Health; developed and implemented the Bachelors of Health Sciences degree and formulated articulation agreements with two year colleges. Teach undergraduate students in the Health Care Administration and Planning program. Courses: Health Research, Health Planning, Environmental Health, Long Term Care Administration, Health Management I, Health Economics, Health Finance, Health Law, Managed Care and Introduction to Public Health. At the graduate level, I taught Topics in Health Administration in the graduate program in Public Administration; served on thesis committees (Meharry Medical College); I coordinate and supervise summer interns; coordinate the Fall and Spring Internship Program; developed a marketing program for the College of Health Sciences Program; re-designed the Health Administration and -

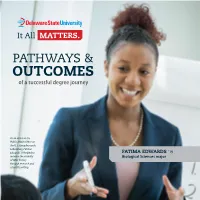

OUTCOMES of a Successful Degree Journey

PATHWAYS & OUTCOMES of a successful degree journey As an intern in the Public Affairs Office at the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Fatima Edwards ’19 helped to FATIMA EDWARDS ‘19 increase the visibility Biological Sciences major of ARL’s history through research and scientific writing. Preparing for success, It All Matters. Every Delaware State University student’s experience is personalized from the start. The Office of Career Services & Student Employment engages students early and often through its “Dive D.E.E.P. into Your Career” campaign. Each incoming freshman develops a resume for quick access to hundreds of employers via the Handshake career platform and progresses toward internships and other career experiences during their four years. Career Services has specialization model, with a career counselor assigned to each academic college and majors, creating customized programming. The office also offers a full range of services from career assessments, career fairs, workshops, career classes, classroom presentations, graduate school application assistance, campus interviews, etiquette dinners, resume assistance, mock interviews and the latest virtual software. Also enhancing their Delaware State University experience, new freshmen begin with an Individual Development Plan facilitated by the Office of Student Success that fosters academic success and professional development for career readiness. Throughout each student’s journey, challenging academics taught by passionate, expert faculty combine with hands-on research, internships, clinical and field experiences, and study abroad opportunities to provide the knowledge and skills to achieve career success or to pursue an advanced degree. OUR STUDENTS’ OUTCOMES of our graduates surveyed in 2017 achieved employment 6 months after graduation or went on to attend graduate school, 86% exceeding the national placement percentage. -

Graduate Education for Negroes in Southern Universities Charles H

Howard University Digital Howard @ Howard University Faculty Reprints 1-1-1940 Graduate Education for Negroes in Southern Universities Charles H. Wesley Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/reprints Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Wesley, Charles H., "Graduate Education for Negroes in Southern Universities" (1940). Faculty Reprints. Paper 204. http://dh.howard.edu/reprints/204 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Reprints by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reprinted from the H arvard Educational Review, Vol. 10, No. 1, Jan., 1940. Graduate Education for Negroes in Southern Universities By Charles H. Wesley I The education of Negroes T h e decision of the United States at all levels is a problem Supreme Court in December 1938, which educators are prone to which was reaffirmed in January blink. On the graduate level 1939, in the case of Lloyd L. Gaines the difficulties beset a smaller vs. S. W. Canada, Registrar of the number with greater force. University and the Curators of the This dispassionate summary University of Missouri has directed of the present conditions by attention to the opportunities of the Dean of Howard Uni Negro students for graduate and versity clarifies the special professional education. This de complexities of graduate Ne cision emphasizing the "equality of gro education and indicates legal right” and the "equality of the general difficulties of the opportunity” of the races within the whole field. -

School of Education 27

700 Park Avenue Norfolk, VA 23504 (757) 823-8600 (800) 274-1821 http://www.nsu.edu/catalog/GraduateCatalog.html Achieving Excellence. Success Beyond Measure. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACADEMIC CALENDARS V WELCOME FROM THE PRESIDENT XII BOARD OF VISITORS XIII WELCOME TO NORFOLK STATE UNIVERSITY 1 GRADUATE EDUCATION 4 DEGREES GRANTED 4 GRADUATE SCHOOL 5 ADMISSIONS 5 RE-ADMISSION 6 TUITION, FEES, AND FINANCIAL INFORMATION 7 FINANCIAL AID FOR STUDENTS 8 ACADEMIC POLICIES 9 ACADEMIC INFORMATION 11 THE CURRICULUM 11 ACADEMIC STANDARDS 12 CAMPUS LIBRARY 14 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICES 15 OFFICE OF THE PROVOST 15 DIVISION OF FINANCE AND BUSINESS 16 DIVISION OF RESEARCH AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT 18 DIVISION OF STUDENT AFFAIRS 19 Recognized Student Organizations 23 DIVISION OF UNIVERSITY ADVANCEMENT 26 SCHOOL OF EDUCATION 27 MASTER OF ARTS IN PRE-ELEMENTARY EDUCATION 28 M.A. – Pre.EE. Online Error! Bookmark not defined.7 MASTER OF ARTS IN PRE-ELEMENTARY EDUCATION WITH LICENSURE IN EARLY CHILDHOOD SPECIAL EDUCATION 31 MASTER OF ARTS IN TEACHING – ELEMENTARY EDUCATON 33 M.A.T. -- Elementary Education (PreK-6) - Online Error! Bookmark not defined. GRADUATE CATALOG I 2012 -14 Table of Contents MASTER OF ARTS IN SPECIAL EDUCATION 33 M.A. in Special Education – General (Non-Teaching) 34 M.A. in Special Education – Teacher Licensure Adapted Curriculum K-12 35 M.A. in Special Education – Concentration in Rehabilitation Counseling 36 M.A. in Special Education – Teacher Licensure General Curriculum K-12 37 MASTER OF ARTS IN TEACHING – SECONDARY EDUCATION 42 M.A.T. -- Biology 43 M.A.T. -- Chemistry 44 M.A.T. -- English 45 M.A.T. -

HBCU Architecture Forum: Spring 2012 Tallahassee, FL

HBCU Architecture Forum: Spring 2012 Tallahassee, FL The Florida A&M University School of Architecture is pleased to host the 3rd Annual HBCU Architecture Forum on Friday, March 30, 2012 and Saturday, March 31, 2012. The annual event provides HBCU architecture programs, faculty and students a unique opportunity for enrichment & exposure. The tentative theme for the 2012 Spring Forum is "Collaboration." Schedule Friday, March 30 04:00 PM Keynote Lecture: Dina A. Griffin, AIA, NOMA Room 121 06:00 PM Dinner with Lecture Guest To Be Determined 06:00 PM Student Evening South Atrium Bleachers Saturday, March 31 09:30 AM HBCU Deans’ Welcome Room 121 10:00 AM Current Work: Hampton (10 students) Room 121 10:30 AM Current Work: Morgan State (5), Prairie View (5) Room 121 11:00 AM Current Work: Howard (20 students) Room 121 11:45 AM Current Work: FAMU (10 students) Tuskegee (5) Room 121 12:30 PM Lunch South Atrium 01:15 PM Panel Discussion I: “Why should I pursue licensure?” Room 121 • Leon Bridges, FAIA, NOMAC • Dina A. Griffin, AIA, NOMA • Dr. Carmina Sanchez-Del-Valle, RA • US General Services Admin. (GSA), to be confirmed 02:00 PM Collaboration Workshops: Florida A&M Univ (3) Room 111, 112 & 234 02:30 PM Collaboration Workshops: Hampton Univ (3) Room 111, 112 & 234 03:00 PM Collaboration Workshops: Howard Univ (2) + Southern Univ (1) Room 111, 112 & 234 03:30 PM Collaboration Workshops: Morgan State, Tuskegee, Prairie View Room 111, 112 & 234 04:00 PM Panel Discussion II: “Reflection & Suggestions” Room 121 • faculty in attendance • faculty in attendance • faculty in attendance • faculty in attendance 04:30 PM Thank you Participating Schools + Contacts Florida A&M University Hampton University Wes Henderson + Carmina Sanchez Howard University Edward D. -

The Founding of Howard University

Howard University Studies in History Volume 1 Article 5 Issue 1 The Founding of Howard University 6-1-1921 The oundinF g of Howard University Walter Dyson Follow this and additional works at: http://dh.howard.edu/hush Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dyson, Walter (1921) "The oundF ing of Howard University," Howard University Studies in History: Vol. 1: Iss. 1, Article 5. Available at: http://dh.howard.edu/hush/vol1/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Howard @ Howard University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Howard University Studies in History by an authorized administrator of Digital Howard @ Howard University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dyson: The Founding of Howard University THE FOUNDING OF HOWARD UNIVERSITY m THE OCCASION, 1860— 1866 LAVERY in the United States was gone forever by November 19, S 1866, notwithstanding the many attempts to restore it in disguise.1 “ I suppose," said a speaker on the occasion of the fourth anniversary of the freedom of the Negroes of Washington, D. C., “ it will no longer he presumption to call you fellow-citizens, since the Constitution has been so amended as forever to prohibit slavery and involuntary servitude, except in punishment for crime, and since the ‘Civil Rights Bill’ has become a law of the land.” 2 There were then in the United States about -1,000,000 3 of these newly enfranchised fellow-citizens. Of these, the great majority were so poor and so ignorant as not to he able to enjoy fully the privileges or exercise properly the duties of their high position. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Lennox A. Graham, DM, Assistant Professor and Chair 4781 Bonnie Brae Road Baltimore MD 21208 Mobile: 443-742-9905 Email: [email protected] PREVIEW STATEMENT Lennox Graham is an innovative educator and practitioner with extensive experience in the design, delivery, evaluation, and enhancement of effective instructional programs and management assessment models. He is a highly articulate and effective communicator with excellent team building and interpersonal skills; working well with individuals at all levels to accomplish strategic goals. EDUCATION 2008 Doctor of Management in Organizational Leadership University of Phoenix, Phoenix, Arizona 1982 Master of Science in Education Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama 1980 Bachelor of Science in Agronomy Tuskegee University, Tuskegee, Alabama PROFESSIONAL CERTIFICATIONS - Certified CITI Conflict of Interest - Certified Blood Pressure Assessment Instructor, State of Maryland, Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. - Certified Smoking Cessation Instructor, Maryland Red Cross - Certified Online Faculty Instructor, University of Phoenix, 2009 EXPERIENCE 2016 – Present Assistant Professor, and Chair Health Sciences and Management, Howard University, Washington, DC Courses Taught: Community Health Management (3 credit hours), Health Systems Management I & II (6 credit hours), Global Health Management (3 credit hours), HIV/AIDS Policy and Administration for Health Professionals (3 credit hours), Ethics for Health Professionals (2 credit hours) 2008 – Present Distance Learning