Supporting Central African Refugees in Cameroon Policy and Practice in Response to Protracted Displacement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5 – 03/07/2020 Humanitarian Implementation Plan (Hip)

Year: 2020 Version: 5 – 03/07/2020 HUMANITARIAN IMPLEMENTATION PLAN (HIP) CENTRAL AFRICA1 The full implementation of this version of the HIP is conditional upon the necessary appropriation being made available from the 2020 general budget of the European Union AMOUNT: EUR 117 200 000 The present Humanitarian Implementation Plan (HIP) was prepared on the basis of the financing decision ECHO/WWD/BUD/2020/01000 (Worldwide Decision) and the related General Guidelines for Operational Priorities on Humanitarian Aid (Operational Priorities). The purpose of the HIP and its annex is to serve as a communication tool for DG ECHO2's partners and to assist them in the preparation of their proposals. The provisions of the Worldwide Decision and the General Conditions of the Agreement with the European Commission shall take precedence over the provisions in this document. This HIP covers Cameroon, the Central African Republic (CAR), Chad and Nigeria. It may also respond to sudden or slow-onset new emergencies in Gabon, Equatorial Guinea, Sao Tomé and Principe, if important unmet humanitarian needs emerge, given the exposure to risk and vulnerabilities of populations in these countries. 0. MAJOR CHANGES SINCE PREVIOUS VERSION OF THE HIP Fourth modification as of 03/07/2020 The total budget of the HIP is increased by EUR 5 million (Central African Republic: EUR 5 million). The perspectives in the Central African Republic for 2020 are very worrisome and the COVID-19 pandemic will exacerbate needs in all sectors. This additional funding will cover unmet needs. The eligible sectors in CAR are: (i) protection (ii) health and nutrition, (iii) food assistance and livelihoods, (iv) water, sanitation and hygiene, (v) shelter (vi) emergency preparedness and response and (vii) education in emergencies. -

Assessment Report

Needs Assessment for Self-Reliance of CAR refugees in Gado, Borgop, Ngam, Mbile, Lolo and Timangolo Camps, and In Touboro Assessment Report Monitoring & Evaluation department November-December 2017 Page 1 of 30 Contents List of abbreviations ...................................................................................................................................... 3 List of figures ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Key findings/executive summary .................................................................................................................. 5 Operational Context ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Introduction: The CAR situation In Cameroon .............................................................................................. 7 Objectives ..................................................................................................................................................... 8 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................. 9 Study Design ............................................................................................................................................. 9 Qualitative Approach ........................................................................................................................... -

Central African Republic Situation

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 40 8-21 November 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS 410,000 IDPs including Central African Republic (CAR): On 20 November, UNHCR was invited by the Representative of President Denis Sassou N'Guesso of the Republic 61,244 of Congo (RoC), and current mediator to the crisis, to participate in a in Bangui meeting held in Bangui to discuss the upcoming elections in the country and the feasibility of ensuring the participation of Central African refugees. The meeting was also attended by the Deputy Special 424,580 Representative of the Secretary-General (DSRSG) and UN Resident Total number of CAR refugees in Coordinator of CAR, Mr. Aurélien Agbenonci, the ambassadors of France, neighbouring countries Cameroon, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), RoC and China, and representatives of the European Union and USAID. UNHCR 187,300 welcomed the Central African authorities’ willingness to hold inclusive elections and reiterated its readiness to assist in discussions between New CAR refugees in neighbouring authorities in CAR and countries of asylum. countries since Dec. 2013 Cameroon: On 5 November, a suspected case of cholera was reported 8,012 on the site Timangolo. The patient reportedly came from Gado via Gbiti Refugees and asylum seekers in three days before symptoms appeared. UNHCR coordinated an CAR immediate multi-sectoral response with WHO, UNICEF, NGO partners and local authorities, including the mobilization of a WASH task force to carry out communication and raising awareness, ensuring potable water treatment and disinfection. FUNDING USD 255 million Population of concern requested for the situation Funded A total of 834,580 people of concern 38% IDPs in CAR 410,000 Gap 62% Refugees in Cameroon 242,578 PRIORITIES Refugees in Chad 93,120 . -

Refugee Health Problems in the Central African Sub- Region: the Role of Traditional Medicine

JOURNAL OF THE CAMEROON ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Vol. 14 No. 3 (JANUARY 2019) Research Article REFUGEE HEALTH PROBLEMS IN THE CENTRAL AFRICAN SUB- REGION: THE ROLE OF TRADITIONAL MEDICINE Justine G Nzweundji and 1*Gabriel A Agbor 1*Centre for Research on Medicinal Plants and Traditional Medicine, Institute of Medical Research and Medicinal Plants Studies, Cameroon P.O. Box: 13033, Yaoundé-Cameroon. Email: [email protected]; Phone: +237 677223674 Email: [email protected]; Phone: +237 93667518 *Corresponding author ABSTRACT This review focuses on the role that African Traditional Medicine can play in addressing the health problems of refugees in the central sub-region with focus on Cameroon. This paper is based on a review of literature on the influx of refugees and their well-being. Over 400 000 refugees live in Cameroon particularly in the Far North (Nigerians) and in the Eastern (Central Africans Refugees) Regions of Cameroon. About 80 per cent of the refugees arriving in Cameroon suffer from serious ailments such as malaria, diarrhea, anemia and respiratory tract infections, while more than 20 per cent of children are severely malnourished. To curb these diseases UNHCR and NGOs provide medications to refugees which often arrive late; some of which at times expire in stock or some different distribution centres run out of stock. An aid could come from Traditional Medicine Practitioners who have been very effective in management of disease conditions in refugee camps in some countries in the world. The Cameroon Traditional Medicine if well-developed will do same to act as first-aid before the arrival of conventional medicine or complement western medicine to manage patients who do not accept western medicine because of cultural believes. -

Field Evaluation of Local Integration of Central African Refugees in Cameroon

FIELD EVALUATION OF LOCAL INTEGRATION OF CENTRAL AFRICAN REFUGEES IN CAMEROON FINAL FIELD VISIT REPORT U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE TASK ORDER No. SAWMMA13F2592 Evaluating the Effectiveness of Humanitarian Engagement and Programming in Promoting Local Integration of Refugees in Zambia, Tanzania, and Cameroon September 22, 2014 This document was produced for the Department of State by Development by Training Services, Inc. (dTS). FIELD EVALUATION OF LOCAL INTEGRATION OF CENTRAL AFRICAN REFUGEES IN CAMEROON FINAL FIELD VISIT REPORT Evaluating the Effectiveness of Humanitarian Engagement and Programming in Promoting Local Integration of Refugees in Zambia, Tanzania, and Cameroon Submitted to: Office of Policy and Resource Planning, Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration (PRM), U.S. Department of State Prepared by: Development and Training Services, Inc. (dTS) TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYM LIST ......................................................................................................................................... ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... iii CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 A. SCOPE OF WORK ........................................................................................................................... 1 B. METHODOLOGY ............................................................................................................................. -

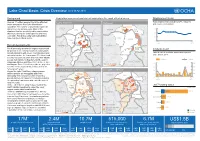

Lac Chad Snapshot 06 Apr 2017 Copy

Lake Chad Basin: Crisis Overview (as of 06 Apr 2017) Background Population movement and violent incidents in the most affected areas Displacement trend Total displacements including IDPs, refugees Around 17 million people live in the affected Latest incidents1 Refugees2 areas across the four Lake Chad basin and returnees (in million) countries. The number of displaced people has Diffa NIGER Lac 3.0 tripled over the last two years. Most of the Diffa NIGER 106.2k displaced families are sheltered by communities 7.8k 2.5 that count among the world’s poorest and most Lac Kukawa vulnerable. Food insecurity and malnutrition 2.0 Borno Yobe have reached critical levels. Borno Yobe Jere Dikwa 1.5 Mar Mar Maiduguri 2016 2017 Konduga Gwoza Recent developments NIGERIA Waza CHAD NIGERIA CHAD Mayo Moskota Far-North Food insecurity across the region is projected 86.3k Incidents trend1 to worsen in the coming months as communities Far-North already struggling with severe food shortages and Total of violent incidents and deaths reported adversity traverse the lean season. The latest food Adamawa since March 2016 Adamawa security assessments show that more than 50,000 people risk famine in Nigeria’s north-eastern Incidents Deaths Adamawa, Borno and Yobe states between June CAMEROON CAMEROON 0,4k 10 15 35 70k 40 400 and August. Some 5.2 million people are projected Incidents to suffer severe food scarcity, a third of them at Diffa 30 300 “emergency” levels. 3 5 Internally Displaced Persons Accessible territories 200 Across the Lake Chad Basin, almost seven 20 million people are struggling with food 10 100 Diffa NIGER Diffa insecurity. -

Central African Refugees (CAR) and Host Population Living in the East, Adamawa, North Regions of Cameroon

UNHCR & WFP Joint Assessment Mission (JAM) Central African refugees (CAR) and host population living in the East, Adamawa, North Regions of Cameroon - Primary data collected from 21 to 31 January 2019 - Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ______________________________________________________ 4 ACRONYMS ________________________________________________________________ 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY _____________________________________________________ 7 1. Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 11 1.1 Background to the Joint Assessment Mission _____________________________________ 12 1.2 Objective of the Joint Assessment Mission ________________________________________ 12 1.3 Overall picture of the refugee situation: origin, population size and demography, sites, surrounding community relations __________________________________________________ 12 1.4 Verification process and coordination ___________________________________________ 13 2. Description of current Assistance to refugees __________________________________ 14 2.1 Current Assistance provided by UNHCR (Protection, NFI, WASH, Safety Net, Livelihood) ______________________________________________________________________________ 14 2.2 Current assistance provided by the WFP _________________________________________ 17 2.2.1 General Food Distributions ___________________________________________________________ 17 2.2.2 Blanket supplementary feeding 6-23 months ______________________________________________ 18 2.2.3 Asset creation for early recovery, community -

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 41 22-28 November 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS 430,000 Idps Including

CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SITUATION UNHCR REGIONAL UPDATE 41 22-28 November 2014 KEY FIGURES HIGHLIGHTS 430,000 IDPs including 61,244 Central African Republic (CAR): The situation in Zemio, Haut-Mbomou prefecture has returned to calm since the visit of the Humanitarian in Bangui Country Team (HCT) on 22 November. The populations displaced by the events have returned to their homes and mediation efforts between all 422,925 parties to the conflict are underway notably through a plan to set up a Total number of CAR refugees in conflict resolution committee to be steered by UNHCR. The unrest led neighbouring countries to the death of two people, injured 15 people and 84 homes were burnt. 187,814 Cameroon: No new cases of cholera were reported this week, New CAR refugees in neighbouring nevertheless, UNHCR, in collaboration with WHO, UNICEF and the countries since Dec. 2013 Regional Delegation of Public Health (DRSP) continued to sensitize populations in and outside of sites on prevention measures. WHO and UNICEF continued to conduct routine polio and measles vaccinations in 8,012 the border towns of Kentzou, Garoua Boulai, Tocktoyo and Gbiti. Refugees and asylum seekers in During the reporting period, 44 children between the ages of 0 and 59 CAR months received oral polio vaccines and 40 children between the ages of 6 months and 15 years were vaccinated against measles. FUNDING USD 255 million Population of concern requested for the situation A total of 852,925 people of concern Funded 38% IDPs in CAR 430,000 Gap 62% Refugees in Cameroon 240,918 PRIORITIES Refugees in Chad 93,120 . -

Cameroon 2019 Human Rights Report

CAMEROON 2019 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Cameroon is a republic dominated by a strong presidency. The president retains the power over the legislative and judicial branches of government. In October 2018 Paul Biya was reelected president in an election marked by irregularities. He has served as president since 1982. His political party--the Cameroon People’s Democratic Movement (CPDM)--has remained in power since its creation in 1985. New legislative and municipal elections are scheduled to take place in February 2020. Regional elections were also expected during the year, but as of late November, the president had not scheduled them. The national police and the national gendarmerie have primary responsibility over law enforcement and maintenance of order within the country and report, respectively, to the General Delegation of National Security and to the Secretariat of State for Defense in charge of the Gendarmerie. The army is responsible for external security but also has some domestic security responsibilities and reports to the Ministry of Defense. The Rapid Intervention Battalion (BIR) reports directly to the president. Civilian authorities at times did not maintain effective control over the security forces. Maurice Kamto, leader of the Cameroon Renaissance Movement (CRM) party and distant runner-up in the October 2018 presidential elections, challenged the election results, claiming he won. On January 26, when Kamto and his followers demonstrated peacefully, authorities arrested him and hundreds of his followers. A crisis in the Anglophone Northwest and Southwest Regions that erupted in 2016 has led to more than 2,000 persons killed, more than 44,000 refugees in Nigeria, and more than 500,000 internally displaced persons. -

Republic of Cameroon

Submission by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees For the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights’ Compilation Report Universal Periodic Review: 3rd Cycle, 30th Session REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON I. BACKGROUND INFORMATION Cameroon succeeded to the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees in 1961 and acceded to its 1967 Protocol in 1967 (hereinafter jointly referred to as the 1951 Convention). Cameroon has not ratified the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless persons (the 1954 Convention) nor the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness (the 1961 Convention). Cameroon is party to the OAU Convention on the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa. Cameroon enacted Act No. 2005/006 of 27 July 2005 concerning the Status of Refugees and the Decree 2011/389 of 28 November 2011 on Refugee Management Structures. At the time of writing, the relevant refugee management structures, including the National Eligibility Commission, had not yet been fully operationalized in accordance with the above law. UNHCR continues to conduct registration and refugee status determination (RSD) procedures on behalf of the Government of Cameroon. Cameroon hosts 4,209 asylum-seekers and 322,004 refugees as of 30 June 2017. Additionally, Cameroon also has 223,642 internally displaced persons as of March 2017 and an estimated 120,000 persons at risk of statelessness. Refugees from the Central African Republic (CAR) constitute the largest population, with 228,384 individuals, the vast majority of whom (212,534) live in 7 managed sites and over 150 villages in the Eastern, Northern and Adamaoua regions, with the remainder living in urban areas such as Yaoundé and Douala. -

Background on Disaster

Canadian Humanitarian Assistance Fund (CHAF) Disaster Response Strategy Emergency Child Health & Nutrition Response for CAR Refugees in Cameroon 2014 Plan International’s Intervention – CHAF – 2014 July 4, 2014 The Humanitarian Coalition (HC) Canadian Humanitarian Assistance Fund (CHAF) is funded by the Government of Canada Department of Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development (DFATD). It was created in 2014 to ensure timely funding is available to fund lifesaving responses to smaller-scale disasters. The CHAF is a central feature of the Humanitarian Coalition disaster response system. Summary: CAD $327,209 has been allocated to Plan International Canada to respond to the Central African Republic refugee crisis in Cameroon. According to UNHCR, there are more than 100,000 new CAR refugees in Cameroon (and 211,023 in tota). Currently there are 7 refugee sites spread across the country: Gado, Lolo, Mbile, Yokadouma and the recently created Timangolo site in the East; Borgop and Ngam in the Adamawa region in the northern part of Cameroon. A significant number of refugees are living with local host communities. As of June 15, 2014, out of all new arrivals registered so far, 57.6 % are children (UNHCR statistics as of June 15, 2014). The number of new CAR refugees anticipated to be in Cameroon at the end of 2014 is 180,000. To highlight the severity of the situation for CAR refugees arriving in Cameroon, the Deputy High Commissioner for Refugees, Janet Lim, visited Cameroon with a delegation from Geneva in early July. The objective was two-fold: to encourage aid agencies to deploy and/or upscale to address the growing needs in Cameroon; and to advocate for further funding. -

Refugees, Law, and Development in Africa

Michigan Journal of International Law Volume 3 Issue 1 1982 Refugees, Law, and Development in Africa Peter Nobel Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the Immigration Law Commons Recommended Citation Peter Nobel, Refugees, Law, and Development in Africa, 3 MICH. J. INT'L L. 255 (1982). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjil/vol3/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Journal of International Law at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Refugees, Law, and Development in Africa Peter Nobel* INTRODUCTION This article concerns those large movements of people in Africa, which have been called the "African refugee problem." However, large and in- triguing migrations of populations have occurred in Africa for centuries. The earliest migrations reflected the spread of culture, the growth of trade and the development of roving early kingdoms. The unique history behind the refugee dilemma, however, begins with the instability spawned by slave trading and colonialism. Sensitivity to these eras heightens an under- standing of why today's Africa is wrought with economic crises, territorial disputes, unnatural frontiers, misfit ethnic combinations, and more ref- ugees than any other continent. Against this background this article sur- veys the development of African refugee law and assesses current refugee situations on the continent.