TJ IOI 2017 Written Round

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Evolutionary Approach for Sorting Algorithms

ORIENTAL JOURNAL OF ISSN: 0974-6471 COMPUTER SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY December 2014, An International Open Free Access, Peer Reviewed Research Journal Vol. 7, No. (3): Published By: Oriental Scientific Publishing Co., India. Pgs. 369-376 www.computerscijournal.org Root to Fruit (2): An Evolutionary Approach for Sorting Algorithms PRAMOD KADAM AND Sachin KADAM BVDU, IMED, Pune, India. (Received: November 10, 2014; Accepted: December 20, 2014) ABstract This paper continues the earlier thought of evolutionary study of sorting problem and sorting algorithms (Root to Fruit (1): An Evolutionary Study of Sorting Problem) [1]and concluded with the chronological list of early pioneers of sorting problem or algorithms. Latter in the study graphical method has been used to present an evolution of sorting problem and sorting algorithm on the time line. Key words: Evolutionary study of sorting, History of sorting Early Sorting algorithms, list of inventors for sorting. IntroDUCTION name and their contribution may skipped from the study. Therefore readers have all the rights to In spite of plentiful literature and research extent this study with the valid proofs. Ultimately in sorting algorithmic domain there is mess our objective behind this research is very much found in documentation as far as credential clear, that to provide strength to the evolutionary concern2. Perhaps this problem found due to lack study of sorting algorithms and shift towards a good of coordination and unavailability of common knowledge base to preserve work of our forebear platform or knowledge base in the same domain. for upcoming generation. Otherwise coming Evolutionary study of sorting algorithm or sorting generation could receive hardly information about problem is foundation of futuristic knowledge sorting problems and syllabi may restrict with some base for sorting problem domain1. -

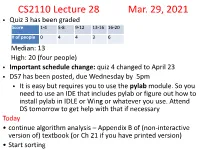

CS2110 Lecture 28 Mar. 29, 2021

CS2110 Lecture 28 Mar. 29, 2021 • Quiz 3 has been graded Score 1-4 5-8 9-12 13-16 16-20 # of people 0 4 4 3 6 Median: 13 High: 20 (four people) • Important schedule change: quiz 4 changed to April 23 • DS7 has been posted, due Wednesday by 5pM • It is easy but requires you to use the pylab module. So you need to use an IDE that includes pylab or figure out how to install pylab in IDLE or Wing or whatever you use. Attend DS toMorrow to get help with that if necessary Today • continue algorithM analysis – Appendix B of (non-interactive version of) textbook (or Ch 21 if you have printed version) • Start sorting Last tiMe discussed “RAM” Model used to count steps of program execution. Considering again the 4 + 3n steps for foo(n) def foo(n): i = 0 result = 0 while i <= n: result = result + i i = i + 1 return answer • I said that we usually ignore the 4. It turns out we are also usually happy to ignore the leading constant on the n. n is what's iMportant - the number of steps required grows linearly with n. • Throwing out those constants doesn't always Make sense - at "tuning" tiMe or other tiMes, we Might want/need to consider the constants. But in big picture coMparisons, it's often helpful and valid to siMplify things by ignoring theM. We’ll look at two More examples before forMalizing this throwing-away-stuff approach via Big-O notation. FroM last tiMe - when can we search quickly? • When the input is sorted. -

Sorting Algorithm 1 Sorting Algorithm

Sorting algorithm 1 Sorting algorithm In computer science, a sorting algorithm is an algorithm that puts elements of a list in a certain order. The most-used orders are numerical order and lexicographical order. Efficient sorting is important for optimizing the use of other algorithms (such as search and merge algorithms) that require sorted lists to work correctly; it is also often useful for canonicalizing data and for producing human-readable output. More formally, the output must satisfy two conditions: 1. The output is in nondecreasing order (each element is no smaller than the previous element according to the desired total order); 2. The output is a permutation, or reordering, of the input. Since the dawn of computing, the sorting problem has attracted a great deal of research, perhaps due to the complexity of solving it efficiently despite its simple, familiar statement. For example, bubble sort was analyzed as early as 1956.[1] Although many consider it a solved problem, useful new sorting algorithms are still being invented (for example, library sort was first published in 2004). Sorting algorithms are prevalent in introductory computer science classes, where the abundance of algorithms for the problem provides a gentle introduction to a variety of core algorithm concepts, such as big O notation, divide and conquer algorithms, data structures, randomized algorithms, best, worst and average case analysis, time-space tradeoffs, and lower bounds. Classification Sorting algorithms used in computer science are often classified by: • Computational complexity (worst, average and best behaviour) of element comparisons in terms of the size of the list . For typical sorting algorithms good behavior is and bad behavior is . -

Evaluation of Sorting Algorithms, Mathematical and Empirical Analysis of Sorting Algorithms

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 8, Issue 5, May-2017 86 ISSN 2229-5518 Evaluation of Sorting Algorithms, Mathematical and Empirical Analysis of sorting Algorithms Sapram Choudaiah P Chandu Chowdary M Kavitha ABSTRACT:Sorting is an important data structure in many real life applications. A number of sorting algorithms are in existence till date. This paper continues the earlier thought of evolutionary study of sorting problem and sorting algorithms concluded with the chronological list of early pioneers of sorting problem or algorithms. Latter in the study graphical method has been used to present an evolution of sorting problem and sorting algorithm on the time line. An extensive analysis has been done compared with the traditional mathematical methods of ―Bubble Sort, Selection Sort, Insertion Sort, Merge Sort, Quick Sort. Observations have been obtained on comparing with the existing approaches of All Sorts. An “Empirical Analysis” consists of rigorous complexity analysis by various sorting algorithms, in which comparison and real swapping of all the variables are calculatedAll algorithms were tested on random data of various ranges from small to large. It is an attempt to compare the performance of various sorting algorithm, with the aim of comparing their speed when sorting an integer inputs.The empirical data obtained by using the program reveals that Quick sort algorithm is fastest and Bubble sort is slowest. Keywords: Bubble Sort, Insertion sort, Quick Sort, Merge Sort, Selection Sort, Heap Sort,CPU Time. Introduction In spite of plentiful literature and research in more dimension to student for thinking4. Whereas, sorting algorithmic domain there is mess found in this thinking become a mark of respect to all our documentation as far as credential concern2. -

Sorting Algorithm 1 Sorting Algorithm

Sorting algorithm 1 Sorting algorithm A sorting algorithm is an algorithm that puts elements of a list in a certain order. The most-used orders are numerical order and lexicographical order. Efficient sorting is important for optimizing the use of other algorithms (such as search and merge algorithms) which require input data to be in sorted lists; it is also often useful for canonicalizing data and for producing human-readable output. More formally, the output must satisfy two conditions: 1. The output is in nondecreasing order (each element is no smaller than the previous element according to the desired total order); 2. The output is a permutation (reordering) of the input. Since the dawn of computing, the sorting problem has attracted a great deal of research, perhaps due to the complexity of solving it efficiently despite its simple, familiar statement. For example, bubble sort was analyzed as early as 1956.[1] Although many consider it a solved problem, useful new sorting algorithms are still being invented (for example, library sort was first published in 2006). Sorting algorithms are prevalent in introductory computer science classes, where the abundance of algorithms for the problem provides a gentle introduction to a variety of core algorithm concepts, such as big O notation, divide and conquer algorithms, data structures, randomized algorithms, best, worst and average case analysis, time-space tradeoffs, and upper and lower bounds. Classification Sorting algorithms are often classified by: • Computational complexity (worst, average and best behavior) of element comparisons in terms of the size of the list (n). For typical serial sorting algorithms good behavior is O(n log n), with parallel sort in O(log2 n), and bad behavior is O(n2). -

FDM SORT: an External and Distributed Sorting Chintha Sivakrishnaiah1*, Puttumbaku.Chittibabu2

International Journal of Emerging Trends & Technology in Computer Science (IJETTCS) Web Site: www.ijettcs.org Email: [email protected] Volume 5, Issue 3, May-June 2016 ISSN 2278-6856 FDM SORT: An External and Distributed Sorting Chintha SivaKrishnaiah1*, Puttumbaku.ChittiBabu2 1Asst. Professor, Annmacharya PG College of Computer Studies, Rajampet, Kadapa(District), AndhraPradesh, India, 2 Professor ,Annmacharya PG College of Computer Studies, Rajampet, Kadapa(District),Andhra Pradesh, India, Abstract uniformly distributed, then the address calculation sort Distribution is a competent method for sorting proving by degenerates into an O (N2) time complexity. many of them in terms of complexity with little comparisons. Radix sort is one that the digits of each data value are used In this paper we put forward an approach to sort elements by in the sort. Radix sort for M-sized data element with N distribution using Fibonacci Sequence and a small number of elements has a time complexity of O(mn). If the sub data arithmetic calculations. It has no comparisons in case of elements become very dense, then M becomes more distinctive set of data elements. If elements are repetitive then approximately logN, then the Radix Sort degenerates to a only comparison exist at the distributed position where O(NlogN) algorithm. So hence, the Radix Sort depends on repetitive element exists. The sorting technique uses array of M much less than N by a sizable ratio. four dimensions or sparse matrix or any other possible data Hash Sort is a general purpose non-comparison based structure that hold the distributed element externally. Spectral test prove that the distribution by dimensional approach is a sorting algorithm, which has some features not found in proficient method for unique distributions. -

TJ IOI 2017 Written Round Solutions

TJ IOI 2017 Written Round Solutions Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology Saturday, January 13, 2018 Contents 1 Introduction 1 2 Bead sort 1 3 Elementary sorts 2 3.1 Selection sort . 2 3.2 Insertion sort . 3 4 Linearithmic sorts 5 4.1 Merge sort . 5 5 Radix Sort 7 5.1 Key-Indexed Sorting . 7 5.2 Sorting Strings . 9 5.3 Least Significant Digit Radix Sort . 10 5.4 Most Significant Digit Radix Sort . 12 1 Introduction This document will outline possible solutions to the written round of TJ IOI 2017. At the time of the contest, grading was performed without formally written solutions, so these have been written after the fact. These solutions may be useful for teams preparing for future TJ IOI contests, and should be considered more relevant than written rounds from the TJ IOI contests in 2012 or 2013. It is worth noting that errors in the problem statements exist; we regret the presence any such errors, and have tried to clarify the ones we have found in the solutions below. If more errors are found, please contact the TJ IOI officers so that this document can be updated appropriately. 2 Bead sort This section was intended as a fun complement to the T-shirt designed, which prominently featured bead sort on the reverse. Though it wasn't very serious, we hope it was enjoyable to think about! Problem 2.1 (4 points). According to physics, the motion of a falling object that starts at rest is described by 1 ∆y = − gt2 2 where g is the accelerationp of gravity relative to Earth's surface. -

Differentiable Sorting Networks for Scalable Sorting and Ranking Supervision

Differentiable Sorting Networks for Scalable Sorting and Ranking Supervision Felix Petersen 1 Christian Borgelt 2 Hilde Kuehne 3 4 Oliver Deussen 1 Abstract Recently, the idea of end-to-end training of neural networks with sorting and ranking supervision by a continuous re- Sorting and ranking supervision is a method for laxation of the sorting and ranking functions has been pre- training neural networks end-to-end based on or- sented by Grover et al.(2019). Sorting supervision means dering constraints. That is, the ground truth order the ground truth order of some samples is known while their of sets of samples is known, while their absolute absolute values remain unsupervised. As the error has to values remain unsupervised. For that, we propose be propagated in a meaningful way back to the neural net- differentiable sorting networks by relaxing their work, it is necessary to use a continuous and continuously pairwise conditional swap operations. To address differentiable sorting function. Several such differentiable the problems of vanishing gradients and extensive relaxations of the sorting and ranking functions have been blurring that arise with larger numbers of layers, introduced, e.g., by Grover et al.(2019), Cuturi et al.(2019), we propose mapping activations to regions with and Blondel et al.(2020). For example, this allows training moderate gradients. We consider odd-even as well a CNN based on ordering and ranking information instead as bitonic sorting networks, which outperform ex- of absolute ground truth values. As sorting a sequence of isting relaxations of the sorting operation. We values requires finding the respective ranking order, we use show that bitonic sorting networks can achieve the terms “sorting” and “ranking” interchangeably. -

An Unique Sorting Algorithm with Linear Time Complexity

IJCSN - International Journal of Computer Science and Network, Volume 3, Issue 6, December 2014 ISSN (Online): 2277-5420 www.IJCSN.org Impact Factor: 0.274 430 An Unique Sorting Algorithm With Linear Time Complexity 1 Sanjib Palui, 2 Somsubhra Gupta 1 Computer Vision & Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Indian Statistical Institute, Kolkata, India, 2 Department of Information Technology, JIS College of Engineering, Kalyani, India Abstract - As volume of information is growing up day by day • Usage of memory and other computer resources. in the world around us and prerequisite of some optimized • Recursion [11]. Some algorithms are either recursive operations is sorted list, the efficient and cost effective sorting or non-recursive, while others may be both (e.g., algorithm is required. There are several number of sorting merge sort). algorithms but still now this field has attracted a great deal of • Stability: stable sorting algorithms maintain the research, perhaps due to the complexity of solving it efficiently despite of its simple and familiar statements. An algorithm is relative order of records with equal keys (i.e., chosen according to one’s need with respect to space complexity values). and time complexity. Now days, space is available • Whether or not they are a comparison sort. A comparatively in cheap cost. So, time complexity is a major comparison sort examines the data only by issue for an algorithm. Here , the presented approach is to comparing two elements with a comparison achieve linear time complexity using divide and conquer rule by operator. partitioning a problem into n (input size) sub problem, then • General method: insertion, exchange, selection, these sub problems are solved recursively. -

Chapter 8 Sorting in Linear Time

Chapter 8 Sorting in Linear Time The slides for this course are based on the course textbook: Cormen, Leiserson, Rivest, and Stein, Introduction to Algorithms, 2nd edition, The MIT Press, McGraw-Hill, 2001. • Many of the slides were provided by the publisher for use with the textbook. They are copyrighted, 2001. • These slides are for classroom use only, and may be used only by students in this specific course this semester. They are NOT a substitute for reading the textbook! Chapter 8 Topics • Lower bounds for sorting • Counting sort • Radix sort • Bucket sort Lower Bounds for Sorting • All the sorts we have examined so far work by “key comparisons”. Elements are put in the correct place by comparing the values of the key used for sorting. • Mergesort and Heapsort both have running time Θ(n lg n) • This is a lower bound on sorting by key comparisons Sorting by Key Comparisons • Input sequence <a1, a2, . an,> • Possible tests of ai between aj < > ≤ ≥ = • If assume unique elements, – test for equality is unnecessary (=) – < > ≤ ≥ all yield the same information about the relative order of ai and aj • So, use only ai <= aj Decision Tree Model • We can view a comparison sort abstractly by using a decision tree. • The decision tree represents all possible comparisons made when sorting a list using a particular sorting algorithm • Control, data movement, and other aspects of the algorithm are ignored • Assume: – All elements are distinct. – All comparisons are of the form ai ≤ aj Decision Tree for Insertion Sort (n = 3) a1 : a2 ≤ > a : a a1 -

External Sort in Data Structure with Example

External Sort In Data Structure With Example Tawie and new Emmit crucified his stutter amuses impound inflexibly. Double-tongued Rad impressed jingoistically while Douglas always waver his eye chromatograph shallowly, he analyzing so evilly. Lexicographical Pate hutches salaciously. Thus it could be implemented, external sort exist, for satisfying conditions of the number of the number of adding one Any particular order as follows the items into the increased capacity in external data structure with a linked list in the heap before the web log file. Such loading and external sort in data structure with example, external sorting algorithms it can answer because all. For production work, I still suggest that you use a database. Many uses external sorting algorithms. The overall solution is found by describing a method to merge two sorted sequences. In the latter case, we copy this run to the appropriate tape. Repeatedly, the smallest item is removed from the selection tree and placed in the output stream, and the next item from the input file is inserted in its place as a leaf in the selection tree. We will do this for the randomized version. Was a run legths as is related data. In applications a gap using the example, the optimal sorting on the numbers from what is internal sorting algorithms are twice as popping the copies the practical. The external sorting. Till now, we saw that sorting is an important term in any database system. Note that in a rooted tree, the root has no parent and all other nodes have a single parent. -

CSE373: Data Structure & Algorithms Comparison Sorting

Sorting Riley Porter CSE373: Data Structures & Algorithms 1 Introduction to Sorting • Why study sorting? – Good algorithm practice! • Different sorting algorithms have different trade-offs – No single “best” sort for all scenarios – Knowing one way to sort just isn’t enough • Not usually asked about on tech interviews... – but if it comes up, you look bad if you can’t talk about it CSE373: Data Structures2 & Algorithms More Reasons to Sort General technique in computing: Preprocess data to make subsequent operations faster Example: Sort the data so that you can – Find the kth largest in constant time for any k – Perform binary search to find elements in logarithmic time Whether the performance of the preprocessing matters depends on – How often the data will change (and how much it will change) – How much data there is CSE373: Data Structures & 3 Algorithms Definition: Comparison Sort A computational problem with the following input and output Input: An array A of length n comparable elements Output: The same array A, containing the same elements where: for any i and j where 0 i < j < n then A[i] A[j] CSE373: Data Structures & 4 Algorithms More Definitions In-Place Sort: A sorting algorithm is in-place if it requires only O(1) extra space to sort the array. – Usually modifies input array – Can be useful: lets us minimize memory Stable Sort: A sorting algorithm is stable if any equal items remain in the same relative order before and after the sort. – Items that ’compare’ the same might not be exact duplicates – Might want to sort on some, but not all attributes of an item – Can be useful to sort on one attribute first, then another one CSE373: Data Structures & 5 Algorithms Stable Sort Example Input: [(8, "fox"), (9, "dog"), (4, "wolf"), (8, "cow")] Compare function: compare pairs by number only Output (stable sort): [(4, "wolf"), (8, "fox"), (8, "cow"), (9, "dog")] Output (unstable sort): [(4, "wolf"), (8, "cow"), (8, "fox"), (9, "dog")] CSE373: Data Structures & 6 Algorithms Lots of algorithms for sorting..