John T. Martin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uc Irvine School of Law Commencement Dinner • May 4, 2012

SCHOOL OF LAW FOUNDING DONORS In Grateful Acknowledgement of Those Whose Foresight and Generosity Made Possible the Building of the Law School for the 21st Century The Donald Bren Foundation Anonymous Joan Irvine Smith & Athalie R. Clarke Foundation Marilyn and John Long Raymond Pryke Melody and Mark P. Robinson, Jr. Acacia Research Corporation Allen Matkins Leck Gamble Mallory & Natsis LLP Andrews & Thornton, Attorneys at Law Philip K. Anthony DecisionQuest Diane and Hon. Joseph L. Dunn Fidelity National Financial Lynn and Douglas K. Freeman Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, LLP Thomas V. Girardi Irell & Manella LLP Jones Day Foundation Knobbe, Martens, Olson & Bear, LLP Latham & Watkins LLP Rosalyn M. Laudati UC IRVINE SCHOOL OF LAW COMMENCEMENT DINNER • MAY 4, 2012 SCHOOL OF LAW FOUNDING DONORS Morrison & Foerster, LLP O'Melveny & Myers, LLP James L. Payne Saveri & Saveri, Inc. Snell & Wilmer, LLP Ellen Bancroft Marcia Brandwynne Susan M. and Richard K. Bridgford Stuart Byer and Jeffrey Rehm Paul J. Couchot The Dorsey & Whitney Foundation Experian Information Solutions, Inc. Vincencia and Ronald C. Lazof Thomas R. Malcolm Manatt, Phelps & Phillips, LLP Minyard & Morris LLP Microsemi Corporation Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Orange County Bar Association Charitable Fund Orange County Trial Lawyers Association Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP Ronald Simon Family Foundation Ygal and Justice Sheila Prell Sonenshine Ann and Marc Winthrop Winthrop Couchot PC UC IRVINE SCHOOL OF LAW COMMENCEMENT DINNER • MAY 4, 2012 SCHOOL OF LAW FOUNDING DONORS American Board of Trial Advocates, Jeffrey M. Verdon Law Group, LLP Orange County Chapter Justice Stephen K. Tamura BARBRI Scholarship Foundation Bell, McAndrews & Hiltachk, LLP Kaplan Inc. -

Lessons from Monitoring Trends in Abundance of Marine Mammals

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 2006 LESSONS FROM MONITORING TRENDS IN ABUNDANCE OF MARINE MAMMALS Barbara L. Taylor NMFS, [email protected] Melissa Martinez NMFS Tim Gerrodette NMFS Jay Barlow NMFS, [email protected] Yvana N. Hrovat University of California - Santa Barbara Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Taylor, Barbara L.; Martinez, Melissa; Gerrodette, Tim; Barlow, Jay; and Hrovat, Yvana N., "LESSONS FROM MONITORING TRENDS IN ABUNDANCE OF MARINE MAMMALS" (2006). Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. 318. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/318 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MARINE MAMMAL SCIENCE, 23(1): 157–175 (January 2007) C 2006 by the Society for Marine Mammalogy No claim to original US government works DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2006.00092.x LESSONS FROM MONITORING TRENDS IN ABUNDANCE OF MARINE MAMMALS BARBARA L. TAYLOR MELISSA MARTINEZ TIM GERRODETTE JAY BARLOW NMFS, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, 8604 La Jolla Shores Drive, La Jolla, California 92037-1508, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] YVANA N. HROVAT Donald Bren School of Environmental Science and Management, University of California, Santa Barbara, Bren Computing, 3408 Bren Hall, UCSB, Santa Barbara, California 93106-3060, U.S.A. -

UCI Law: the First Half Century

UC Irvine UC Irvine Law Review Title UCI Law: The First Half Century Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6m42w9rk Journal UC Irvine Law Review , 1(1) ISSN 2327-4514 Author DiMento, Joseph F.C. Publication Date 2011-03-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Assembled_Issue_1v18 (Do Not Delete) 3/16/2011 11:31 AM UCI Law: The First Half Century Joseph F.C. DiMento* I. The Very Early Years .................................................................................................... 26 II. The Middle Years: Almost Accomplished ............................................................... 31 III. The Unstoppable Attempt (1999–2007) ................................................................ 34 A. Academic Planning Council Call for New Initiatives: The Law School Proposal ........................................................................................... 34 B. Approval, Momentum, Resistance ............................................................... 38 C. Academic Council and UC Regents ............................................................. 41 IV. The First Decisions .................................................................................................... 43 A. The Founding Dean ....................................................................................... 43 B. Funding ............................................................................................................. 45 C. Facilities ........................................................................................................... -

Biographies of the Symposium Presenters

Nature Climate Solutions Symposium March 10, 2016 Biographies Julie Alvis Julie Alvis has served as deputy assistant secretary for the California Natural Resources Agency since 2008. She provides administrative oversight and coordination for Park- and Water- bond-funded programs within the Agency and its departments. Julie also serves as key staff to the California Strategic Growth Council, a cabinet-level committee that is coordinating state efforts in preparing for climate change, and investing in communities to improve air and water quality, protect natural resources, increase the availability of affordable housing, improve transportation, and promote public health. Most recently, Julie has lead the development of the Sustainable Agricultural Lands Conservation program, which seeks to avoid increases in greenhouse gas emissions resulting from the conversion of agricultural land to urban uses. She previously served as Assistant to the California Bay-Delta Authority board and the California Bay-Delta Public Advisory Committee. Following graduation from the University of California at Davis in 1994, Julie worked several years as an editor for educational and private publishing firms prior to her career with the State of California. Kit Batten Dr. Kit Batten is the Executive Director of the UC Davis Policy Institute for Energy, Environment and the Economy. Prior to her appointment at UC Davis, Dr. Batten served as Global Climate Change Coordinator at the US Agency for International Development where she led climate change mitigation and adaptation programming in 40 countries around the world. Appointed by the White House to coordinate climate change activities across USAID, Dr. Batten led U.S. government engagement with the Tropical Forest Alliance 2020 and supported several other large U.S. -

Californiainfluencers

CaliforniaInfluencers alifornia, once a conservative stronghold and the cradle of the Reagan Revolution, has been trending Democratic for years Cnow—and this year it was one of the few states where Demo- crats held their own against the extremely strong national Republican tide. In the top statewide contests, voters decisively chose veteran liberal Democrats Barbara Boxer for senator and Jerry “Moonbeam” Brown for governor over political newcomers who argued that their corporate experience made them ideally suited to guide the state through dire eco- nomic times. Democrats also continue to hold a significant edge in the state’s congressional delegation. While they may tilt to the left on average, successful California politi- cians run the gamut from Barbara Lee, the East Bay representative who was the only member of Congress to vote against the 2001 resolution authorizing the use of force in response to the 9/11 attacks, to Devin Nunes, the Central Valley representative who called the Obama admin- istration’s health care reform bill part of a plan to impose a “Socialist utopia” on the American people. Here is our list of the top 100 players in California politics today. TOP 50 Democrats Jerry Brown staff, helped position Schwarzeneg- state, and his record of victories speaks The governor-elect is an everlasting po- ger for re-election and remains heavily for itself. litical tactician and campaigner. He has involved. held local office, statewide office and Dave Low ran for national office before starting all Eli Broad A powerful lobbyist at the California over again. A Los Angeles real estate developer and School Employees’ Association, he is a philanthropist, Broad is a major donor to resource for those in the labor move- Susan Kennedy Democrats and their causes. -

Annual Report 2016-2017

Power of the Collective ANNUAL REPORT OF PRIVATE GIVING FOR THE YEAR ENDING JUNE 30, 2017 Index Power of the Collective Collective Visioning.................................................... 6 Generosity Made Visible............................................. 8 Financial Highlights Continuing to Grow................................................... 12 Collective Giving A Community for Culture........................................... 16 Interlinking Resources to Interlink the World............... 18 Collective Gratitude.................................................... 20 Alumni Giving ‘Elemental Education’ Inspires Extraordinary Giving..... 24 ‘Quant’ Alumnus Supports Something Personal.......... 26 Gifting Grads.............................................................. 28 Self-Expression............................................................ 30 Faculty Giving Growth Over Time..................................................... 34 Family Giving Home Team................................................................ 38 A Family Affair............................................................ 40 For the Boughton Family, Communication is Key......... 42 Friends Giving Romance in the Rafters............................................... 46 Collective Interests...................................................... 48 Enduring Influence...................................................... 50 Foundation Giving A Rising Star............................................................... 54 Brainiacs Win Big...................................................... -

Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences 1

Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences 1 Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences Marios C. Papaefthymiou, Dean 6210 Donald Bren Hall Academic Counseling: 949-824-5156 http://www.ics.uci.edu (http://www.ics.uci.edu/) The Donald Bren School of Information and Computer Sciences (ICS) embodies excellence, creativity, and collaborative innovation in computer science and information technology. As the only independent computing school in the University of California system, it is well-positioned to continue its tradition of exploring and advancing the boundaries of a broad, multidisciplinary field on a global scale. ICS faculty have extensive training in traditional computer science, as well as engineering, mathematics and statistics, and the social sciences. The School’s stand-alone structure, as opposed to being part of an engineering school, enables the faculty to take the broadest possible view of computer science and information technology. This breadth is reflected in the diverse set of academic degree options for undergraduate and graduate students, some of which are interdisciplinary and jointly administered with other academic units. The School’s three departments — Computer Science, Informatics, and Statistics — fuel a wide range of instructional and research efforts, including: design of algorithms and data structures; computer architecture and embedded computer systems; networked and distributed systems; systems software; social and mobile computing; artificial intelligence, machine learning and data mining; computer games and virtual worlds; databases and information retrieval; computer graphics and visualization; bioinformatics, computational biology and genomics; computer-supported cooperative work, human-centered computing and human-computer interaction; security and privacy; software engineering; managerial and social aspects of computing technology; and statistics. -

Oc's Wealthiest

7.29.19_OCs_Wealthiest.qxp_Layout 1 7/26/19 11:17 AM Page 5 An Orange County Business Journal Special Report p10 p16 p30 p32 p36 p36 OC’S WEALTHIEST A-G Kiani, Joe 30 Samueli,Henry 9 Ahmanson Jr., Howard F. 32 Luckey, Palmer 30 Schlosberg, Hilton H. 12 Argyros, George 12 Lyon, William 27 Segerstrom Family 12 Bren, Donald 8 Maglica, Anthony 34 Simon, Ron 18 Curci, John L. 32 Maseeh, Fariborz 32 Slavick, James D. 28 Downey, Jim 32 Merage, Paul 16 Smith, Vinny 14 Getty Earhart, Anne Catherine 18 Moreno, Arte 14 Snyder, Lynsi 16 Getty, Caroline Marie 18 Moshayedi, Manouch 36 Stoecker, Dean 28 Glidewell, James 37 Moshayedi, Mark 36 Sun, David 9 Gross, Bill 27 Moshayedi, Mike 36 Gross, Sue 16 Mussallem, Mike 37 T-W Taylor, C. Frederick ‘Fred’ 18 H-M N-S Tsao, Janie 28 Herbert Sr., Gavin 36 Nicholas III, Henry T. 10 Tsao, Victor 28 Honarkar, Mo 37 Olenicoff, Igor 8 Tu, John 9 Hsieh, Anthony 16 Pickup, Richard 34 Wang, William 32 Jabara, Gary 34 Pyott, David 36 Wetterau, Mark 36 Jannard, James 10 Roberts, Duane 36 Wilson, David 34 Jones Jr., Fletcher ‘Ted’ 34 Sacks, Rodney 12 7.29.19_OCs_Wealthiest.qxp_Layout 1 7/25/19 4:06 PM Page 6 7.29.19_OCs_Wealthiest.qxp_Layout 1 7/25/19 4:06 PM Page 7 7.29.19_OCs_Wealthiest.qxp_Layout 1 7/26/19 11:07 AM Page 8 8 ORANGE COUNTY BUSINESS JOURNAL www.ocbj.com JULY 29, 2019 Fashion Island, Newport Center 1. DONALD BREN towers part of portfolio Chairman Irvine Co. -

Name Anthony Burke

Name Anthony Burke Staff Reference: 224 FTE: 1.0 FOR: 1201, Architecture Level: C Status: Employed Function: Teaching and Research Exurban Noir, Research Workshop, Ubicomp 2006 Organge County, California Background In 2006, Anthony Burke, with Eric Paulos (Intel) Ken Anderson (Intel) and Amanda Williams (UC Irvine) developed a research workshop on the exurban conditions of Orange country as a field within which to explore locative and new media tactics as part of UbiComp 2006. Papers were accepted, however the nature of the workshop was as a unique exploration in the field research and rapid design prototyping. Contribution 25% Co-director events, concept, design, coordination and management. This workshop was published as part of the UbiComp 2006 proceedings. Significance The research goal of this ubiquitous computing workshop was to explore techniques for considering not general- purpose holistic solutions to problems within the complex social, cultural, political, and economic ecology of urban life, typically aimed at technology users in a hip 20 something demographic. The aim of our research was to expand the vocabulary of potential urban technologies, enabling a wider range of choices as we form our future urban lifestyles. Combining highly specific field trips with final designs from the workshop were intended to provoke open ended discussions around urban technologies rather than present "killer apps" or final solutions. Our research aims included the elaboration of new multidisciplinary methods and models in design practice, for technology designers, to grapple cognitively and experientially with the exopolis as an urban form and to extend the discourse of locative media and technologies and their relationship to urban space and practices as a maturing dialogue, raising issues that are reflective of this. -

Centennial Campaign for Ucla Issue 2020 Volume 40 Number 4

IRENE AND HOWARD LEVINE • AI LAN AND ROGER KOBAYASHI • STEVE LAWRENCE • THE BILLY AND AUDREY L. WILDER FOUNDATION • GINNY AND DONALD SHIELDS • WOUNDED WARRIOR PROJECT, INC. • NOREEN FRASER FOUNDATION • RESEARCH TO PREVENT BLINDNESS ENDOWMENT FUND INC. • PAUL G. ALLEN VIRTUAL EDUCATION FOUNDATION • JESSICA AND HENRY CHEN • UNITED CEREBRAL PALSY OF LOS ANGELES, VENTURA & SANTA BARBARA COUNTIES • ARCHSTONE FOUNDATION • PHILIP L. PALUMBO LIVING TRUST • LOS ANGELES BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE • WASSERMAN FOUNDATION • MATTEL • BREAST CANCER RESEARCH FOUNDATION • STACEY AND STERLING BALL • CAROLINE AND SIDNEY KIMMEL • RICHARD ONOFRIO • BOBBE FRANKENBERG TRUST ESTATE • CAROL AND MURRAY GRIGOR • AGI HIRSHBERG • ALI JASSIM • ALEXANDRA AND SEAN PARKER • BETTY ENGELSTAD • SHELBY NOTKIN • THE CARL & ROBERTA DEUTSCH FOUNDATION • JANE AND MICHAEL EISNER • THE SIMONS FOUNDATION • ESTATE OF JEAN STEIN • PHASE ONE FOUNDATION • JOANNE AND JACK MARTIN • THE ROSE HILLS FOUNDATION • DELPHINE LEE • FRANK W. CLARK, JR. ESTATE TRUST • MTF BIOLOGICS • TOWER CANCER RESEARCH FOUNDATION • UNIHEALTH FOUNDATION • THE LOUIS AND HAROLD PRICE FOUNDATION • JEAN PERKINS FOUNDATION • HERBERT J. ANDREWS TRUST • RUBY FAMILY FOUNDATION, WENDY AND KEN RUBY TRUSTEES • PROSTATEUCLA CANCER FOUNDATIONHealth • NORMAN & IRMA SWITZER TRUST ESTATE • L.A. CARE HEALTH PLAN • JANE AND TERRY SEMEL • KURE IT, INC. • WILLIAM STIVELMAN • ROMA DOWNEY AND MARK BURNETT • YANKULICH LIVING TRUST • BURROUGHS WELLCOME FUND • CEREBRAL PALSY FOUNDATION • THE AHMANSON FOUNDATION • STAND UP 2 CANCER • J. BRONWYN BATEMAN AND DOUGLAS HERSHEY • LEDUCQ FOUN - DATION • PETER SHAPIRO • THE THALIANS • JANET ODELL • THE ESTATE OF ROY AND JUDI KAUFMAN • PAMELA BUFFETTDavid • HESS Geffen FOUNDATION, School INC. • ALBA of AND Medicine THOMAS TULL • LORI AND MICHAEL MILKEN • JEFFREY FRIEDEN • ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY FOUNDATION • CHOU CHEN • ROCKEFELLER UNIVERSITY • LEONARD APT TRUST • VICKI PARDEE • GLENN D. -

Committee of 4000 Records MS.R.160

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8kp82qz No online items Guide to the Committee of 4000 Records MS.R.160 Chris S. Ervin Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries (cc) 2012 The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California, Irvine Irvine 92623-9557 [email protected] URL: http://special.lib.uci.edu Guide to the Committee of 4000 MS.R.160 1 Records MS.R.160 Contributing Institution: Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries Title: Committee of 4000 records Creator: Committee of 4000 (Calif.) Identifier/Call Number: MS.R.160 Physical Description: 0.2 Linear Feet(1 box) Date (inclusive): 1979-1983 Abstract: This collection consists of documents of and related to the Committee of 4000, a non-profit political action group from Irvine, California. The Committee of 4000 was an organization founded by land leaseholders who disputed the terms of their leasing rights with the Irvine Company in the early 1980s. The collection includes newsletters, correspondence from the Irvine Company, meeting minutes, promotional materials, legal documents, and other material related to the organization's class action lawsuit and activities. Language of Material: English . Access The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the University of California. For permissions to reproduce or to publish, please contact the Head of Special Collections and Archives. Preferred Citation Committee of 4000 Records. MS-R160. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California. Date accessed. For the benefit of current and future researchers, please cite any additional information about sources consulted in this collection, including permanent URLs, item or folder descriptions, and box/folder locations. -

"UCI Law Has Status, Not Tradition" (PDF)

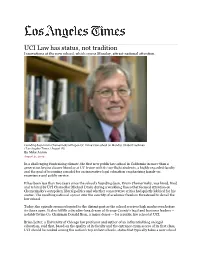

UCI Law has status, not tradition Innovations at the new school, which opens Monday, attract national attention. Founding dean Erwin Chemerinsky will open UC Irvine's law school on Monday. (Robert Lachman / Los Angeles Times / August 18) By Mike Anton August 21, 2009 In a challenging fundraising climate, the first new public law school in California in more than a generation begins classes Monday at UC Irvine with 61 top-flight students, a highly regarded faculty and the goal of becoming a model for an innovative legal education emphasizing hands-on experience and public service. It has been less than two years since the school's founding dean, Erwin Chemerinsky, was hired, fired and rehired by UCI Chancellor Michael Drake during a weeklong fiasco that focused attention on Chemerinsky's outspoken liberal politics and whether conservative critics had quietly lobbied for his ouster. The resulting national uproar over the sanctity of academic freedom threatened to derail the law school. Today, the episode seems relegated to the distant past as the school receives high marks even before its doors open. It also fulfills a decades-long dream of Orange County's legal and business leaders -- notably Irvine Co. Chairman Donald Bren, a major donor -- for a public law school at UCI. Brian Leiter, a University of Chicago law professor and author of an influential blog on legal education, said that, based on the quality of its faculty and the entrance exam scores of its first class, UCI should be ranked among the nation's top 20 law schools, status that typically takes a new school decades to achieve.