The Effect of Light Rail Transit Service on Nearby Property Values: Quasi-Experimental Evidence from Seattle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study

Central Link Initial Segment and Airport Link Before & After Study Final Report February 2014 (this page left blank intentionally) Initial Segment and Airport Link Before and After Study – Final Report (Feb 2014) Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 Before and After Study Requirement and Purposes ................................................................................................... 1 Project Characteristics ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Milestones .................................................................................................................................................................. 1 Data Collection in the Fall .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Organization of the Report ........................................................................................................................................ 2 History of Project Planning and Development ....................................................................................................... 2 Characteristic 1 - Project Scope .............................................................................................................................. 6 Characteristic -

Llght Rall Translt Statlon Deslgn Guldellnes

PORT AUTHORITY OF ALLEGHENY COUNTY LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT V.4.0 7/20/18 STATION DESIGN GUIDELINES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Port Authority of Allegheny County (PAAC) provides public transportation throughout Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. The Authority’s 2,600 employees operate, maintain, and support bus, light rail, incline, and paratransit services for approximately 200,000 daily riders. Port Authority is currently focused on enacting several improvements to make service more efficient and easier to use. Numerous projects are either underway or in the planning stages, including implementation of smart card technology, real-time vehicle tracking, and on-street bus rapid transit. Port Authority is governed by an 11-member Board of Directors – unpaid volunteers who are appointed by the Allegheny County Executive, leaders from both parties in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and Senate, and the Governor of Pennsylvania. The Board holds monthly public meetings. Port Authority’s budget is funded by fare and advertising revenue, along with money from county, state, and federal sources. The Authority’s finances and operations are audited on a regular basis, both internally and by external agencies. Port Authority began serving the community in March 1964. The Authority was created in 1959 when the Pennsylvania Legislature authorized the consolidation of 33 private transit carriers, many of which were failing financially. The consolidation included the Pittsburgh Railways Company, along with 32 independent bus and inclined plane companies. By combining fare structures and centralizing operations, Port Authority established the first unified transit system in Allegheny County. Participants Port Authority of Allegheny County would like to thank agency partners for supporting the Light Rail Transportation Station Guidelines, as well as those who participated by dedicating their time and expertise. -

Central Link Station Boardings, Service Change F

Central Link light rail Weekday Station Activity October 2nd, 2010 to February 4th, 2011 (Service Change Period F) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 4,108 4,465 0 4,465 4,108 University Street Station 106 1,562 1,485 96 1,591 1,658 Pioneer Square Station 225 1,253 1,208 223 1,433 1,476 International District/Chinatown Station 765 1,328 1,121 820 1,887 2,148 Stadium Station 176 201 198 242 374 443 SODO Station 331 312 313 327 645 639 Beacon Hill Station 831 379 400 958 1,230 1,337 Mount Baker Station 699 526 549 655 1,249 1,180 Columbia City Station 838 230 228 815 1,066 1,045 Othello Station 867 266 284 887 1,151 1,153 Rainier Beach Station 742 234 211 737 952 971 Tukwila/International Blvd Station 1,559 279 255 1,777 1,814 2,055 SeaTac/Airport Station 3,538 0 0 3,181 3,538 3,181 Total 10,678 10,718 21,395 Central Link light rail Saturday Station Activity October 2nd, 2010 to February 4th, 2011 (Service Change Period F) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 3,124 3,046 0 3,046 3,124 University Street Station 54 788 696 55 750 843 Pioneer Square Station 126 495 424 136 550 631 International District/Chinatown Station 412 749 640 392 1,052 1,141 Stadium Station 156 320 208 187 364 506 SODO Station 141 165 148 147 290 311 Beacon Hill Station 499 230 203 508 702 738 Mount Baker Station 349 267 240 286 588 553 Columbia City Station 483 181 168 412 651 593 Othello Station 486 218 235 461 721 679 -

Southeast Transportation Study Final Report

Southeast Transportation Study Final Report Prepared for Seattle Department of Transportation by The Underhill Company LLC in association with Mirai Associates Inc Nakano Associates LLC PB America December 2008 Acknowledgements Core Community Team Pete Lamb, Columbia City Business Association Mayor Gregory J. Nickels Joseph Ayele, Ethiopian Business Association Mar Murillo, Filipino Community of Seattle Denise Gloster, Hillman City Business Association Seattle Department of Transportation Nancy Dulaney, Hillman City Business Association Grace Crunican, Director Pamela Wrenn, Hillman City Neighborhood Alliance Susan Sanchez, Director, Policy and Planning Division Sara Valenta, HomeSight Tracy Krawczyk, Transportation Planning Manager Richard Ranhofer, Lakewood Seward Park Neighborhood Sandra Woods, SETS Project Manager Association Hannah McIntosh, Associate Transportation Planner Pat Murakami, Mt. Baker Community Club Dick Burkhart, Othello Station Community Advisory Board SETS Project Advisory Team Gregory Davis, Rainier Beach Coalition for Community Seattle Department of Transportation Empowerment Barbara Gray, Policy, Planning and Major Projects Dawn Tryborn, Rainier Beach Merchants Association Trevor Partap, Traffi c Management Seanna Jordon, Rainier Beach Neighborhood 2014 John Marek, Traffi c Management Jeremy Valenta, Rainier/Othello Safety Association Peter Lagerway, Traffi c Management Rob Mohn, Rainier Valley Chamber of Commerce Randy Wiger, Parking Thao Tran, Rainier Valley Community Development Fund Dawn Schellenberg, Public -

Sound Transit Transit Development Plan 2013-2018 and 2012 Annual Report

Transit Development Plan 2013-2018 and 2012 Annual Report Public Hearing Held: July 11, 2013 Operations and Administration Committee Referral to Board: July 18, 2013 Board of Directors Approval for Submittal: July 25, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................2 I: ORGANIZATION .....................................................................................................................2 II: PHYSICAL PLANT ................................................................................................................5 III: SERVICE CHARACTERISTICS ...........................................................................................6 IV: SERVICE CONNECTIONS ................................................................................................. 10 V: ACTIVITIES IN 2012 ............................................................................................................ 12 VI: PLANNED ACTION STRATEGIES, 2012 – 2018 .............................................................. 19 VII: PLANNED ACTIVITIES, 2012 – 2018 ............................................................................... 20 VIII: CAPITAL IMPROVEMENT PROGRAM, 2012 – 2018 ..................................................... 23 IX: OPERATING DATA, 2012 – 2018 ...................................................................................... 23 X: ANNUAL REVENUES AND EXPENDITURES, 2012 – 2018 ............................................. -

The Effects of Light-Rail Transit on Affordable Housing in Seattle, WA

Jackson The Effects of Light-Rail Transit on Affordable Housing in Seattle, WA John Jackson, Masters of Community and Regional Planning 16’ Department of Planning, Public Policy, and Management University of Oregon May 2016 1 Jackson Table of Contents CHAPTER ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................ 3 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 4 RESEARCH CONTEXT ................................................................................................................ 8 METHODOLOGY ....................................................................................................................... 14 DATA ........................................................................................................................................... 17 NEIGHBORHOOD WALKING ANALYSIS PHOTOS ............................................................. 24 NEIGHBORHOOD WALKING ANALYSIS RESULTS ........................................................... 30 DISCUSSION, CONCLUSION, AND RECOMMENDATIONS ............................................... 32 REFERENCES ............................................................................................................................. 35 2 Jackson Acknowledgements This project wouldn’t be possible without the guidance of my mother, Meri Robinson- Jackson. She has guided me through this journey through graduate school -

RIGHT SIZE PARKING Final Report

jobs and people. jobs and people. and jobs jobs and people. jobs and people. jobs and people. jobs and people. jobs and people. and jobs jobs and people. jobs and people. RIGHT SIZE PARKING Final Report AUGUST 2015 Project partners Consultant team Rick Williams Consulting Project contact information: Daniel Rowe, Transportation Planner King County Metro Transit [email protected] Report prepared by VIA Architecture August 2015 Contents Co 1 Introduction 1 2 Research 5 3 Web Tool 15 4 Demonstration Projects 21 5 Stakeholder Involvement & Project Outreach 33 6 Recommendations & Next Steps 37 7 Appendix 39 (this page intentionally blank) What is the “right size” for parking? Right-sizing parking means striking a balance between parking supply and demand. Why does Right Size Parking matter? Parking is expensive to build. Construction of parking in multi-family projects costs between $20,000 - $40,000 per stall, which has an impact on rent charged to tenants. King County is over-parked. The Right Size Parking study found that on average, multi- family buildings in King County supply 40% more parking than is actually utilized. Excess parking has negative effects on communities. Oversupply of parking leads to increased automobile ownership, vehicle miles traveled, congestion and housing costs. The Right Size Parking project was designed to address the issues surrounding multi- family residential parking supply in King County, assembling local information on parking demand to guide parking supply and management decisions in the future. www.rightsizeparking.org RSP Final Report i ii RSP Final Report Introduction 1 Project overview Who benefits from RSP? The Right Size Parking (RSP) project is an innovative, data- driven research and outreach effort focused on helping Developers, public decision makers, and communities local jurisdictions and developers to balance parking supply all have the potential to benefit from the outcomes of and demand for multi-family buildings. -

2017 Volunteer Compendium

2017 VOLUNTEER COMPENDIUM 2017 SIFF VOLUNTEER COMPENDIUM 1 THANKS TO OUR VOLUNTEER PROGRAM SPONSORS TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 2017 SIFF VOLUNTEER COMPENDIUM 3 Thank you again. Whether this is your first year or tenth as a volunteer, whether you give us a few hours or several hundred hours of your precious DEAR FRIENDS, time this Festival season, we do hope it’s enjoyable, and that you return year after year! We are thrilled to have you join us in hosting the 43rd Annual Seattle International Film Festival. We are about to embark on 25 days featuring With deep appreciation and thanks, about 400 films from 80 countries at 16 venues around the city, including our new SIFF Lounge Presented by Vulcan Productions at The Pan Pacific Hotel and New Works-In-Progress Filmmaker Forums. You make this feat possible. On behalf of the entire SIFF team – Board, staff, filmmakers, festival guests and patrons – we want to thank you for being such an important part of our work and helping bring the largest film Sarah Wilke Beth Barret festival in the US to fruition. EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR INTERIM ARTISTIC DIRECTOR [email protected] [email protected] In 2016, SIFF volunteers invested nearly 22,000 hours supporting more than 225,000 attendees, at over 5600 events, screenings and festivals. Your commitment to SIFF’s work in our community makes what we do every day possible. SIFF: OUR MISSION As a volunteer, you serve on the “front lines” of SIFF – for so many of our SIFF’s mission is to create experiences that bring people together to attendees, you will be the face of the Festival. -

Central Link Station Boardings, Service Change E

Central Link light rail Weekday Station Activity June 12th to October 1st, 2010 (Service Change Period E) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 4,798 4,989 0 4,989 4,798 University Street Station 95 1,650 1,590 98 1,686 1,747 Pioneer Square Station 239 1,329 1,285 239 1,524 1,568 International District/Chinatown Station 752 1,338 1,207 826 1,959 2,163 Stadium Station 375 538 437 446 812 983 SODO Station 337 320 339 351 676 670 Beacon Hill Station 795 355 350 957 1,144 1,313 Mount Baker Station 629 462 484 621 1,113 1,083 Columbia City Station 855 236 248 841 1,103 1,077 Othello Station 855 254 255 875 1,110 1,129 Rainier Beach Station 715 211 209 700 924 911 Tukwila/International Blvd Station 1,705 318 323 1,923 2,028 2,241 SeaTac/Airport Station 4,456 0 0 3,841 4,456 3,841 Total 11,808 11,716 23,524 Central Link light rail Saturday Station Activity June 12th to October 1st, 2010 Excludes DSTT closure weekend of June 12-13, 2010 (Service Change Period E) Northbound Southbound Total Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Boardings Alightings Westlake Station 0 4,859 4,971 0 4,971 4,859 University Street Station 70 1,139 1,011 69 1,081 1,208 Pioneer Square Station 237 795 687 191 924 986 International District/Chinatown Station 527 957 979 540 1,506 1,498 Stadium Station 329 743 654 434 982 1,178 SODO Station 182 195 188 160 370 355 Beacon Hill Station 540 249 332 674 872 923 Mount Baker Station 405 319 320 373 725 691 Columbia City Station 548 204 230 539 778 743 -

Draft Transit Development Plan 2021-2026 and 2020 Annual Report

Transit Development Plan 2021-2026 and 2020 Annual Report Adopted by the Board of Directors [TO BE UPDATED IN FINAL DRAFT] Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) Information: In accordance with the Americans with Disability Act, this document is available in alternate formats upon request. Persons who are deaf or hard of hearing may make a request by calling the Washington State Relay at 711. Title VI Notice to Public: Sound Transit operates its programs and services without regard to race, color or national origin in accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act. Any person who believes she or he has been unlawfully discriminated against for these reasons may file a complaint with Sound Transit. More information on Sound Transit's Title VI Policy and the procedures to file a complaint may be obtained by: calling 888-889-6368; TTY Relay 711; emailing [email protected]; mailing to Sound Transit, Attn: Customer Service, 401 S. Jackson St. Seattle, Washington 98104-2826; or visiting our offices located at 401 S. Jackson St. Seattle, Washington 98104. A complaint may be filed directly with the Federal Transit Administration Office of Civil Rights, Attention: Complaint Team, East Building, 5th Floor – TCR, 1200 New Jersey Avenue, SE, Washington, DC 20590 or call 888-446-4511. Para obtener información sobre la política de no discriminación del Título VI en relación con la discriminación por motivos de raza, color u origen nacional, comuníquese al 800-823-9230. 인종, 피부색 또는 출신 국가를 기반으로 한 차별에 관한 제6조 차별방지 정책 정보에 대해서는 800-823-9230로 연락하십시오. За информацией о политике недопущения дискриминации, относящейся к дискриминации по признакам расы, цвета кожи или национального происхождения в соответствии с Разделом VI, обращайтесь по телефону 800-823-9230. -

Columbia City Station Apartments 4484 Martin Luther King Way South DPD Project Number: 3011443

Columbia City Station Apartments 4484 Martin Luther King Way South DPD Project Number: 3011443 SMR ARCHITECTS 911 Western Ave, Suite 200 Seattle, WA 98104 Christina Bollo, Applicant 206.623.1104 Mercy Housing NW Columbia City Station Apartments Section A: Response to Early Design Guidance Section B: Request for Further Guidance Section C: Departure Requests Section D: Background Information A01:Table of Contents B01: Elevation Evolution C01: Structure Width and Depth (L4) D01: Zoning Information West Before and After D02: Zoning Analysis A02: Site Information C02: Modulation Width (L4) Development Objectives B02: Elevation Evolution D03: Design Guidelines EDG Notes East Before and After C03: Blank Façades (NC1-40) D04: Surrounding Development A03: Streetscape Compatibility B03: Elevation Evolution C04: Height of Unit Above Grade (NC1-40) Site Plan (Before and After) North and South, Before and After D05: Surrounding Development Design Guideline A-2 C05: Setback Between Zones (NC1-40 at L2) D06: Streetscapes B05: Overview of Color Schemes A04: Respect for Adjacent Sites Massing at Southeast Corner (Before and After) D07: Streetscapes B06: Red and Grays Design Guideline A-5 D08: Façade Analysis B07: Red and Creams A05: Transition Between Residence and Street D09: Formal Concept Analysis Lighting Plan Design Guideline A-6 B08: Navy and Olives D11: Garage Plan A06: Relationship to Future Development to North B09: Navy and Olives plus Red D12: Level 1 Plan Design Guideline C-1 B10: Siding Options D13: Level 2 Plan A07: Pedestrian Path D14: Level 3 Plan A08: Hierarchy of Entries D15: Level 4 Plan Design Guideline D-1 D16: Roof Plan A09: Reducing Visual Impact of Garage East Elevation Before and After D17: Lighting Cutsheets Design Guideline D-2, D-5 D18: Relevant Built Work TABLE OF CONTENTS A01 SMR ARCHITECTS RECOMMENDATION MEETING . -

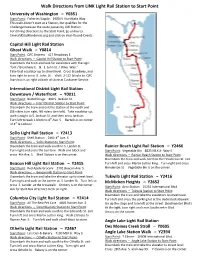

Walk Directions from LINK Light Rail Station to Start Point

Walk Directions from LINK Light Rail Station to Start Point University of Washington – Y0351 Start Point: Fisheries Supply 1900 N. Northlake Way This walk doesn’t start at a Station, but qualifies for the Challenge because the route passes by UW Station. For driving directions to the Start Point, go online to: EmeraldCityWanderers.org and click on Year-Round-Events. Capitol Hill Light Rail Station Ghost Walk – Y0814 Start Point: QFC Grocery 417 Broadway E. Walk directions – Capitol Hill Station to Start Point: Disembark the train and look for escalators with the sign: “Exit / Broadway E. & E. John St. / Olive Way.” Take that escalator up to street level. Cross Broadway, and turn right to cross E. John. St. Walk 2-1/2 blocks to QFC. Start box is on right at back of store at Customer Service. International District Light Rail Station Downtown / Waterfront – Y0011 Start Point: Bartell Drugs 400 S. Jackson St. Walk directions – Intn’l District Station to Start Point: Disembark the train and exit the station at the north end (SB riders turn right, NB riders turn left). Take escalator up, walk straight to S. Jackson St. and then cross Jackson. Turn left to walk 1 block to 4 th Ave. S. Bartells is on corner of 4 th & Jackson. SoDo Light Rail Station – Y2413 Start Point: Shell Station 2461 4 th Ave. S. Walk directions – SoDo Station to Start Point: Disembark the train and walk south to S. Lander St. Rainier Beach Light Rail Station – Y2466 Turn right and cross the bus lane. Walk one block and Start Point: Vegetable Bin 8825 MLK Jr.