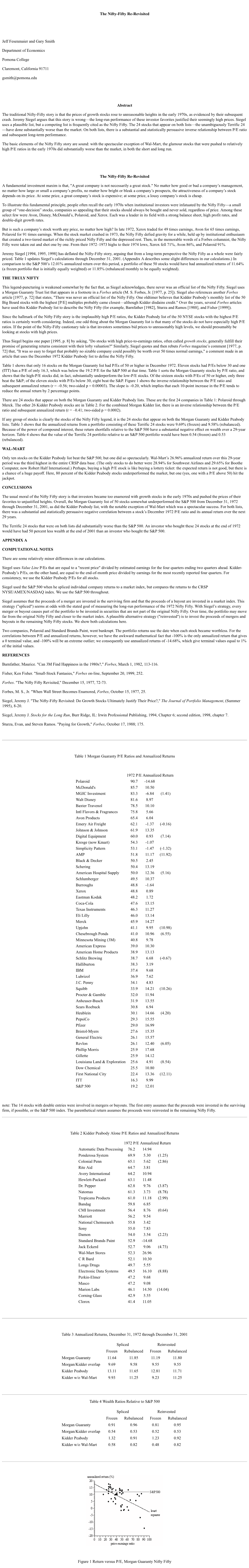

The Nifty-Fifty Re-Revisited Jeff Fesenmaier and Gary Smith

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Semi-Annual Report

Semi-Annual Report December 31, 2008 (Unaudited) Fund Adviser: Auxier Asset Management LLC 5285 Meadows Road Suite 333 Lake Oswego, Oregon 97035 Toll Free: (877) 3AUXIER or (877) 328-9437 AUXIER FOCUS FUND A MESSAGE TO OUR SHAREHOLDERS DECEMBER 31, 2008 AUXIER FOCUS FUND PERFORMANCE UPDATE December 31, 2008 AUXFX RETURNS VS. S&P 500 INDEX Auxier Focus Fund S&P 500 Index Difference* 09/30/08 – 12/31/08 -14.65% -21.94% 7.29 12/31/07 – 12/31/08 -24.52% -37.00% 12.48 12/31/06 – 12/31/07 5.71% 5.49% 0.22 12/31/05 – 12/31/06 11.75% 15.79% -4.04 12/31/04 – 12/31/05 4.58% 4.91% -0.33 12/31/03 – 12/31/04 10.73% 10.87% -0.14 12/31/02 – 12/31/03 26.75% 28.69% -1.94 12/31/01 – 12/31/02 -6.79% -22.10% 15.31 12/31/00 – 12/31/01 12.67% -11.88% 24.55 12/31/99 – 12/31/00 4.05% -9.10% 13.15 Since Inception 7/9/99 47.22% -24.30% 71.52 * in percentage points Average Annual Returns 1 Year 3 Year 5 Year Since Inception for the period ended 12/31/08 Auxier Focus Fund (24.52)% (3.75)% 0.65% 4.16% (Investor Shares) (7/9/99) S&P 500 Index (37.00)% (8.36)% (2.19)% (2.89)% Performance data quoted represents past performance and is no guarantee of future results. Current performance may be lower or higher than the performance data quoted. -

Dire Straits in Valuations; Stocks for Free;

MONEY FOR NOTHING DIRE STRAITS IN VALUATIONS; STOCKS FOR FREE; THE IMPERATIVE OF NO; AND – THE BERKSHIRE FUMBLEROOSKIE, PLUS MORE! 2019 LETTER TO CLIENTS February 14, 2020 CONTENTS MONEY FOR NOTHING DIRE STRAITS IN VALUATIONS; STOCKS FOR FREE; THE IMPERATIVE OF NO; AND – THE BERKSHIRE FUMBLEROOSKIE, PLUS MORE! IN THE LETTER – INTRODUCTION 5 KUDOS 6 INTRINSIC VALUE UPDATE – ADVANTAGES ARE GREATEST AT MARKET HIGHS 8 Forward Expectations 10 Fundamentals Versus the Market 12 THE PETER PRINCIPLE 15 On a Mission 15 The Peter Principle 17 ESG 19 THE IMPERATIVE OF NO: THE LUXURY OF PATIENCE 21 The First Step is the Hardest 21 Understandability 22 Second Verse Same as the First – Business Quality 25 Leverage 26 Management Quality 28 Price Matters 32 THE RELUCTANT ACTIVIST 33 O’Sullivan Industries 34 Mercury General 36 AVX 38 Berkshire Hathaway 41 BLINDERS AT A PEAK 42 The Two-Year Two-Step 42 100 Years of Peaks and Troughs 43 DON’T FEAR THE REPO 47 History 48 Teledyne 48 The “Modern” Era 48 RSU’s Crash the Option Party 50 DEFANGING THE FAB 5 57 Microsoft 57 The Fab 5 59 When Perfection Meets Reality 60 The Nifty Fifty 61 Lower the Bar 62 2 ACTIVE V. PASSIVE UPDATE – Just Set the Table Please 67 READ AND LISTEN 68 BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY: THE SKY IS FALLING 69 Interval Training 70 Above the Fold 75 Bye-Bye Book Value 77 If a Tree Falls in the Forest 80 The Fumblerooskie 85 The Dual Yardsticks of Intrinsic Value 86 Book Value Receives a Complement 87 Oh, What a Night 91 Berkshire Hathaway: Ten-Year Expected Return 94 Estimating Fourth Quarter and Full-Year -

Valuing Growth Stocks: Revisiting the Nifty Fifty

FEATURE ARTICLE VALUING GROWTH STOCKS: REVISITING THE NIFTY FIFTY By Jeremy Siegel The lofty levels This article examines a group of high-flying growth stocks that soared in the reached by the Nifty early 1970s, only to come crashing to earth in the vicious 1973–74 bear market. These stocks are often held up as examples of speculation based on Fifty in the early ‘70s unwarranted optimism about the ability of growth stocks to continue to is often held up as an generate rapid and sustained earnings growth. And it was not just the public, example of but large institutions as well that poured tens of billions of dollars into these unwarranted stocks. After the 1973–74 bear market slashed the value of most of the “Nifty Fifty,” many investors vowed never again to pay over 30 times earnings for a speculation. But a stock. glance in the But is the conventional wisdom justified that the bull market of the early rearview mirror 1970s markedly overvalued these stocks? Or is it possible that investors were indicates investors right to predict that the growth of these firms would eventually justify their were right to predict lofty prices? To put it in more general terms: What premium should an that the growth of investor pay for large, well-established growth stocks? these firms would THE NIFTY FIFTY eventually justify their prices. The Nifty Fifty were a group of premier growth stocks, such as Xerox, IBM, Polaroid, and Coca-Cola, that became institutional darlings in the early 1970s. All of these stocks had proven growth records, continual increases in dividends (virtually none had cut its dividend since World War II), and high market capitalization. -

October 27, 2000

July 20, 2017 Dear PCM Clients and Friends: We have written before about the massive construction program in Wayzata. We think it is worth bringing up again, because June marked the end of the five-year redevelopment project in the heart of Wayzata, a $342 million project called the Promenade of Wayzata. It, if it can be described as “it” because it consists of so many parts, is replacing the old Wayzata Bay Center, for which ground was broken five years ago on June 12, 2012. It is still hard for us to get our arms around what can be packed into 14.5 acres, which was a swamp with cattails and ducks when we moved here in 1966. The Promenade really consists of five “blocks,” which include Folkestone, a three-building senior community of 148 independent living apartments, 58 assisted living units, 30 skilled nursing units and 18 memory care apartments, all owned by Presbyterian Homes. Folkestone also features a “town center” with a library, movie theater and swimming pool, as well as 250 underground parking stalls. Another block to the west is also part of the senior housing, but includes dining and shopping, as well as a major grocery store, which has been closed because it just didn’t live up to expectations. The block to the south consists of apartments, more shopping and dining. The center block, or Regatta, consists of 63 luxury condominiums with retail in the lower level and, of course, underground parking. The last piece of this five-block puzzle is The Landing, a combination of a 92-room boutique hotel, restaurant, retail and 31 luxury condominiums ranging in size from 1,200 to 4,000 square feet, and $825,000 to $4 million in price. -

The New Nifty Fifty + Peak Reopening and Is Stock Leadership Rotating from Large Growth to Small Value?

Commentary The New Nifty Fifty + Peak Reopening And Is Stock Leadership Rotating from Large Growth to Small Value? KEY TAKEAWAYS • Today’s largest stocks bear a striking resemblance to—and in some ways differ markedly from—yesteryear’s Nifty Fifty. Jurrien Timmer • At the same time, we may be seeing a rotation in market leadership, albeit perhaps Director of Global Macro paused, from large cap growth to small cap value stocks. Fidelity Global Asset Allocation • I see the economy as near “peak reopening,” and I think the stock market is near “peak rate of change,” i.e., continued growth but at a diminishing rate. • At some point, the Federal Reserve may need to decide whether to intervene or to allow real yields to be set by the capital markets. Nifty Fifty Redux With large cap growth stocks back in the lead in recent weeks—propelling the S&P 500 to fresh all-time highs in the process—I figured now would be a good time to take a look at what I’ll call the new Nifty Fifty. (For those who’ve forgotten, the original Nifty Fifty were a handful of high-growth blue chips of the 1960s and ‘70s that withstood even the vicious 1973–1974 bear market.) I entertained this topic last summer, but a lot has happened since then. We can get a sense of similarity among historical patterns by comparing, in percentage terms, the relative return of the S&P 500’s 50 largest stocks (by market capitalization) versus the remaining 450 over time (Exhibit 1). -

The Nifty Fifty

May 2018 | Lessons from the past 1960 The Nifty Fifty History is full of bubbles, booms and busts, corporate under management, with new money flowing in at a net collapses and crises, which illuminate the present annual rate of $2.4bn. Mutual fund trading already accounted financial world. for a quarter of all transactions in the stock market.5 At Stewart Investors we believe that an appreciation The rise of star fund managers was another feature of the of financial history can make us more effective ‘go-go’ years. Gerry Tsai was perhaps the best known of the investors today. new portfolio managers. His Manhattan Fund raised $247m in 1966 – the largest amount ever raised by an investment The Nifty Fifty was the name given to a group of US fund at that point.6 growth stocks which performed very strongly in the 1960s and early 1970s, becoming symbolic of the spirit of the Wall Street was transformed over the decade by an influx of times. The companies, which included household names new personnel. By 1969, half of salesmen and investment like McDonald’s and Polaroid, traded on very high analysts had come into the business since 1962.7 They only valuations over many years. had experience of a prolonged bull market, another factor sustaining the bubble in the Nifty Fifty. The Go-Go Years The Nifty Fifty The 1960s were buoyant years for the US economy and stock market. From the mid-60s the term ‘go-go’ was used The Nifty Fifty was a group of 50 stocks identified by to describe an aggressive way of operating in the stock market commentators, although it was never an official market, which involved trading for quick profits. -

New Era Value Investing: a Disciplined Approach to Buying

NEW ERA VALUE INVESTING RELATIVE VALUE DISCIPLINE This book describes an innovative investment strategy called “Relative Value Discipline,” which provides a framework for in- vesting in traditional dividend-paying value stocks, as well as undervalued growth stocks. The graphic below illustrates how the stock selection process works step by step to winnow a thousand large cap stocks down to a focused portfolio of twenty to thirty holdings. Investment Universe • Large cap U.S. stocks • Approximately 1,000 companies • Market cap over $3 billion Divdend-Paying Stocks Low-Yielding Stocks in Traditional Value Sectors in Growth-Oriented Sectors Screened using: Screened using: Relative Dividend Yield Relative Price-to-Sales Ratio (RDY) valuation model (RPSR) valuation model Focus List • Approximately 100 companies • Low price versus historical company average Twelve Fundamental Factor Analysis Qualitative Factors/Quantitative Factors • Buggy Whip (product obsolescence) • Positive Free Cash Flow • Niche Value (market leadership) • Dividend Coverage and Growth • Top Management • Asset Turnover • Sales/Revenue Growth • Investment in Business/ROIC • Operating Margins • Equity Leverage • Relative P/E • Financial Risk Portfolio Construction • Rank each Focus List security based on both qualitative and quantitative analysis • Focused portfolio (usually between twenty and thirty holdings) • Highest confidence picks • Calculated sector bets versus S&P 500 NEW ERA VALUE INVESTING A Disciplined Approach to Buying Value and Growth Stocks NANCY TENGLER John -

Ashdon Investment Management Lessons from the Nifty Fifty

Ashdon Investment Management Lessons from the Nifty Fifty Joshua Collinsworth February 2016 In the preparation of this presentation, Ashdon relied on data taken from sources it believes are creditable. As such, Ashdon believes such data to be accurate and reliable. While Ashdon has taken efforts to insure the data’s accuracy, Ashdon cannot verify that the data used are free of error. Ashdon has relied on such data to calculate and offer hypothetical scenarios in this presentation. Ashdon has presented such data in historical context and for historical hypothetical purposes. Historical results are not a guarantee of future investment performance. Ashdon has not used such data to intentionally mislead, nor has Ashdon intentionally omitted data that is relevant to its hypothetical scenarios. Ashdon assumes no responsibility for errors or omissions that result from the data it has relied on in this presentation, the sources of the data, or the calculation of such data. This presentation makes no offering of investment. The investment options discussed here must be offered through specific presentation of the terms and risks of the specific offering. 1 | P a g e Lessons from the Nifty Fifty Through the end of 2014 and the entirety of 2015, the US equity markets lost breadth, a term used in bull markets to describe the number of Market environments advancing companies relative to declining companies in the market. When like this are not breadth is full, companies across the board are going up in value (a healthy uncommon, and we bull market), and when breadth is weak, market “leadership” gets believe that this narrower and narrower into a handful of companies. -

Wise Passivity, Cautious Opportunism

The VIEW from BURGUNDY The VIEW from BURGUNDY NOVEMBER 2001 WISE PASSIVITY, CAUTIOUS OPPORTUNISM “‘To enjoy the benefits of time’ was one of the chief stellar growth records, which seemed to be able to maxims of the statecraft of the age. Time untied so outperform the market averages under any many knots, cancelled the necessity for so many circumstances. They were known as “one-decision” desperate decisions, revealed so many unexpected shifts stocks because you could supposedly buy them at any of pattern in a kaleidoscopic world, that the shrewdest price and never sell them. We thought that it would be statesmen were glad to take refuge in a wise passivity, a instructive to go through the list of Nifty Fifty stocks to cautious opportunism.” 1 see how they have performed over the past 30 years. The above quotation, though far from its context, Our goal is to determine why some companies have could stand as a brief manifesto for the kind of value prospered and some have faltered, and to draw lessons investing we try to practice. We sometimes tell our for investing today. clients that we would like to have the same portfolio at The origin of our quest was in Jeremy Siegel’s 1994 the end of a year that we had at the beginning, and try book, Stocks for the Long Run. In one chapter, Siegel to explain to them how hard we had to work to achieve shows that if you had bought the Nifty Fifty on that level of apparent inactivity. They usually think we January 1, 1972 and held the stocks until May 31, 1993, are kidding, but we’re not. -

Piquemal Houghton Global Equities Rc

PIQUEMAL HOUGHTON GLOBAL EQUITIES Quarterly Report RC EUR - LU2261172618 30/06/2021 A sub fund of PIQUEMAL HOUGHTON FUNDS (the “Fund”) Investment Objective of the SICAV The investment objective of the SICAV is to outperform the MSCI AC World over the long term by selecting quality companies listed across the globe and buy them at a price that reflects their intrinsic value. We are totally benchmark agnostic. We have a fundamental, bottom-up, highly concentrated, high conviction strategy. Cumulative Performance as of 30/06/2021 Discrete Performance (%) Last Month QTD YTD Since Inception Jan 2021 Feb 2021 March 2021 April 2021 PIQUEMAL HOUGHTON GLOBAL EQUITIES - RC EUR 0,64% 0,34% 0,96% 2,09% -1,53% -0,38% 2,56% -1,44% May 2021 June 2021 1,16% 0,64% Portfolio Comment for Q2 2021 The anticipated end of the pandemic, better growth prospects across the globe and massive fiscal stimulus sent global stock markets to new all-time highs in the first half of 2021. In this bullish environment, our portfolio’s performance has clearly been disappointing. This disappointment stemmed from three main reasons: • Firstly, while a lot of valuations were stretched, we remained disciplined and kept approximately a third of our portfolio in cash or near cash instruments. This explains a third of the underperformance. Today, we have 20% in cash, that we will progressively deploy on stock market moves, as we have already done so over the past few months. • Secondly, 28% of the fund is invested in China. This market has registered one of the worst performances globally so far this year (+4% YTD), as a result of China’s introduction of monetary tightening earlier than anyone else globally, rising geopolitical tensions, and the US imposing restrictions on Chinese companies’ ability to list publicly. -

Copyrighted Material

ch10_IND_4502.qxd 9/8/05 10:53 AM Page 277 INDEX Abercrombie & Fitch, 109, buy-side, 100–101, 259 strategy, 98 114, 145 recommendations, 35–36 types of, 217 About.reuters.com, 120 reports, 40 Asset management firms, Accounting periods, 43 track record of, 120 41 Accounting systems, types Angel investing, defined, Auditor’s report, 60 of, 57–58 225 Audits, financial Accounts payable, 51–52, Angel investors statements, 61 273 characterized, 41–42 Automatic payment plan, Accounts receivable, 273 group meetings, as 17, 239 Acquisitions, 61, 76 information resource, Automobile industry, 156 Active management, 258 37–38 AutoZone, 126–127 Activity ratios, 66 Annual accounting period, Average annual returns, Actuaries Share indexes, 72 43 216 Additional paid-in capital, Annual reports, Average price, 174 273 information provided Aggressive growth, 19 by, 27, 40–41, 49, 53, Back-office systems, 110 Aggressive stocks, 224 56, 59–60, 96, 234 Bad debt, 112 Albertson’s, 134 Apple Computers, 132, 227 Bad news Alcoa, 108 Application forms, as buying opportunity, Allied Chemical, 253 dividend reinvestment 162–164 ALLTEL Corp., 82, 84 plans (DRPs), 179 impact of, 148 Alpha, 138 Applied Materials, 35, 108, Balance sheet Alternative investing, 22, 156 analysis of, 111–112, 151 225, 237–238, 258 Arbitrage, 258 annual, 50 Alternative minimum tax Ask, 25 assets, 51–52 (AMT), 258 Asset(s) cash, 53–54 Amazon.com, 132 allocation of, see Asset defined, 273 America Online, 119 allocation format of, 53 American Express, 68, 135 characteristics of, 51, 62, importance -

New Era Value Investing: a Disciplined Approach to Buying

NEW ERA VALUE INVESTING RELATIVE VALUE DISCIPLINE This book describes an innovative investment strategy called “Relative Value Discipline,” which provides a framework for in- vesting in traditional dividend-paying value stocks, as well as undervalued growth stocks. The graphic below illustrates how the stock selection process works step by step to winnow a thousand large cap stocks down to a focused portfolio of twenty to thirty holdings. Investment Universe • Large cap U.S. stocks • Approximately 1,000 companies • Market cap over $3 billion Divdend-Paying Stocks Low-Yielding Stocks in Traditional Value Sectors in Growth-Oriented Sectors Screened using: Screened using: Relative Dividend Yield Relative Price-to-Sales Ratio (RDY) valuation model (RPSR) valuation model Focus List • Approximately 100 companies • Low price versus historical company average Twelve Fundamental Factor Analysis Qualitative Factors/Quantitative Factors • Buggy Whip (product obsolescence) • Positive Free Cash Flow • Niche Value (market leadership) • Dividend Coverage and Growth • Top Management • Asset Turnover • Sales/Revenue Growth • Investment in Business/ROIC • Operating Margins • Equity Leverage • Relative P/E • Financial Risk Portfolio Construction • Rank each Focus List security based on both qualitative and quantitative analysis • Focused portfolio (usually between twenty and thirty holdings) • Highest confidence picks • Calculated sector bets versus S&P 500 NEW ERA VALUE INVESTING A Disciplined Approach to Buying Value and Growth Stocks NANCY TENGLER John