The 2007 Punjab Election: Exploring the Verdict

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

59Th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa Report

59th Commonwealth Parliamentary Conference, Johannesburg, South Africa Report The 59th CPC was held in Johannesburg, South Africa from 28th August to 6th September, 2013. Due to ongoing Parliament Session Hon’ble Speaker, Lok Sabha and Members of Parliament could not attend the Conference due to extended Parliament Session. Following delegates from State CPA Branches of India attended the Conference: Sl. No. Name of CPA Branch/Delegates 1 Arunachal Pradesh Shri Wanglin Lowangdong Speaker Arunachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly 1. 2 Assam Branch Shri Bhimananda Tanti Deputy Speaker Assam Legislative Assembly 2. 3 Bihar Branch Shri Uday Narain Choudhary Speaker Bihar Vidhan Sabha 3. 4 Delhi Branch Dr. Yoganand Shastri Speaker Delhi Legislative Assembly 4. 5 Goa Branch Shri Rajendra Arlekar Speaker Goa Legislative Assembly 5. 6 Gujarat Branch Shri Ashwinbhai Kotwal, MLA Shri Shankarbhai Lagdhirbhai Chaudhary, MLA Gujarat Legislative Assembly 6. 7 Haryana Branch Shri Kuldip Sharma Speaker Haryana Vidhan Sabha 8 Himachal Pradesh Branch Shri Brij Behari Lal Butail Speaker Himachal Pradesh Legislative Assembly 9 Jammu and Kashmir Branch Shri Mubarak Gul Speaker Jammu and Kashmir Legislative Assembly 10 Jharkhand Branch Shri Chandreshwar Prasad Singh MLA Jharkhand Legislative Assembly 11 Karnataka Branch Shri D.H. Shankaramurthy Chairman Karnataka Legislative Assembly 12 Kerala Branch Shri G. Karthikeyan, Speaker, Kerala Legislative Assembly 13 Manipur Branch Shri Thokchom Lokeshwar Singh Speaker Manipur Legislative Assembly 14 Meghalaya Branch Shri Abu Taher Mondal Speaker Meghalaya Legislative Assembly 15 Mizoram Branch Shri John Rotluangliana, Deputy Speaker, Mizoram Legislative Assembly 16 Nagaland Branch Shri Chotisuh Sazo Speaker Nagaland Legislative Assembly Shri Kiyanilie Peseyie Minister, Govt. of Nagaland Regional Representative -CPA Executive Committee 17 Puducherry Branch Shri V. -

FOREWORD the Need to Prepare a Clear and Comprehensive Document

FOREWORD The need to prepare a clear and comprehensive document on the Punjab problem has been felt by the Sikh community for a very long time. With the release of this White Paper, the S.G.P.C. has fulfilled this long-felt need of the community. It takes cognisance of all aspects of the problem-historical, socio-economic, political and ideological. The approach of the Indian Government has been too partisan and negative to take into account a complete perspective of the multidimensional problem. The government White Paper focusses only on the law and order aspect, deliberately ignoring a careful examination of the issues and processes that have compounded the problem. The state, with its aggressive publicity organs, has often, tried to conceal the basic facts and withhold the genocide of the Sikhs conducted in Punjab in the name of restoring peace. Operation Black Out, conducted in full collaboration with the media, has often led to the circulation of one-sided versions of the problem, adding to the poignancy of the plight of the Sikhs. Record has to be put straight for people and posterity. But it requires volumes to make a full disclosure of the long history of betrayal, discrimination, political trickery, murky intrigues, phoney negotiations and repression which has led to blood and tears, trauma and torture for the Sikhs over the past five decades. Moreover, it is not possible to gather full information, without access to government records. This document has been prepared on the basis of available evidence to awaken the voices of all those who love justice to the understanding of the Sikh point of view. -

The History of Punjab Is Replete with Its Political Parties Entering Into Mergers, Post-Election Coalitions and Pre-Election Alliances

COALITION POLITICS IN PUNJAB* PRAMOD KUMAR The history of Punjab is replete with its political parties entering into mergers, post-election coalitions and pre-election alliances. Pre-election electoral alliances are a more recent phenomenon, occasional seat adjustments, notwithstanding. While the mergers have been with parties offering a competing support base (Congress and Akalis) the post-election coalition and pre-election alliance have been among parties drawing upon sectional interests. As such there have been two main groupings. One led by the Congress, partnered by the communists, and the other consisting of the Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) and Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) has moulded itself to joining any grouping as per its needs. Fringe groups that sprout from time to time, position themselves vis-à-vis the main groups to play the spoiler’s role in the elections. These groups are formed around common minimum programmes which have been used mainly to defend the alliances rather than nurture the ideological basis. For instance, the BJP, in alliance with the Akali Dal, finds it difficult to make the Anti-Terrorist Act, POTA, a main election issue, since the Akalis had been at the receiving end of state repression in the early ‘90s. The Akalis, in alliance with the BJP, cannot revive their anti-Centre political plank. And the Congress finds it difficult to talk about economic liberalisation, as it has to take into account the sensitivities of its main ally, the CPI, which has campaigned against the WTO regime. The implications of this situation can be better understood by recalling the politics that has led to these alliances. -

Role of Geospatial Technologies to Bridge the Rural and Urban Divide

National Conference on Role of Geospatial Technologies to Bridge the Rural and Urban Divide Organized by Punjab Remote Sensing Centre, Ludhiana in collaboration with Indian Society of Geomatics-Ludhiana Chapter VENUE : Punjab Remote Sensing Centre, Ludhiana, Punjab, India 21-23 February, 2018 (21 st Feb-Tutorials; 22 nd & 23 rd Feb-Conference) MINUTE-TO-MINUTE PROGRAMME FOR INAUGURAL SESSION 09.30 AM : Arrival of the Chief Guest and dignitaries on dias 09.30-09.40 : Welcome by Director, PRSC 09.40-10.00 : Address by Guest of Honour, Director-IIRS/ISRO, Dehradun 10.00-10.15 : Addl. PCCF-cum-CEO, Orissa Remote Sensing Applications Centre, Bhubneshwar 10.15-10.45 : Address by the Chief Guest S. NAVJOT SINGH SIDHU, HON'BLE MINISTER Local Govt., Tourism & Cultural Affairs and Archives & Museum, Govt. of Punjab 10.45-11.00 : Presidential Address Distinguished Scientist Director, SAC/ISRO and President, ISG, Ahmedabad 11.00-11.10 : Vote of Thanks - Secretary, ISG (Ludhiana Chapter) INAUGURATION OF EXHIBITION BY THE HON'BLE CHIEF GUEST 11.10-11.30 BREAK FOR HIGH TEA & NETWORKING TENTATIVE PROGRAMME PLENARY SESSION Auditorium PRSC 11:30-11:50 Dr. A. Senthil Kumar 11:50-12:10 Dr. Sandeep Tripathi 12:10-12:30 Dr. S.S. Ray, Director, MNCFC, New Operational Remote Sensing Delhi Applications in Agriculture Dr. K.R. Manjunath, Scientist SG, ISRO Indian Earth Observations 12:30-12:50 Programme Satellite Missions and Applications 12:50-13:10 Dr. Prakash Chauhan Space Based Monitoring of Air SAC Ahmedabad, Scientist G, Group Pollution Director, SAC, Ahmedabad 13:10-13:30 Dr. -

Fourteenth Lok Sabha I Session (02/06/2004 to 10/06/2004)

&ŽƵƌƚĞĞŶƚŚ>ŽŬ^ĂďŚĂ /^ĞƐƐŝŽŶ;ϬϮͬϬϲͬϮϬϬϰƚŽϭϬͬϬϲͬϮϬϬϰͿ LOK SABHA Bulletin-Part I (Brief Record of Proceedings Wednesday, June 2, 2004/Jyaistha 12, 1926 (Saka) No. 1 11.00 A.M. 1. National Anthem The National Anthem was played. 2. Silence To mark the solemn occasion of the first sitting of the Fourteenth Lok Sabha, members stood in silence for a short while. 11.02 A.M. 3. List of Members elected to Lok Sabha Secretary-General laid on the Table a list (Hindi and English versions), containing the names of members elected to the Fourteenth Lok Sabha at the General Elections of 2004, submitted to the Speaker by the Election Commission of India. 4. Panel of Chairmen The Speaker pro tem announced that he had, under Rule 9 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha, nominated the following members on the Panel of Chairmen:- (1) Shri Balasaheb Vikhe Patil (2) Shri Giridhar Gamang (3) Shri Manabendra Shah 5. Resignation from Membership of Lok Sabha The Speaker pro tem informed the House that the Speaker had received a letter dated the 25th May, 2004 from Shri Mulayam Singh Yadav, an elected member from the Mainpuri Parliamentary Constituency of Uttar Pradesh, resigning from the membership of Lok Sabha and that his resignation had been accepted by the Speaker with effect from the 25th May, 2004. 11.05 A.M. 6. Oath or Affirmation The Speaker pro tem Shri Somnath Chatterjee, having already made affirmation before the President, signed the Roll of Members at the commencement of the sitting and took his seat in the House. -

PM News 38 April 2010.Cdr

PMA Centre for Excellence in Project Management PM NEWS Number 38 December 2009 - March 2010 PMN # 487 Highlights of Global Symposium 2009 The 17th Global Symposium on 'Managing Projects, Programs and Portfolios' was held in Delhi from December 14 to 16, 2009. The Global Symposium invited the best talents from India and abroad to talk about the contemporary trends in project and program management. The GS 2009 International Advisory Council (IAC) consisted of eminent professionals under the Chairmanship of B K Chaturvedi, Member, Planning Commission, Govt. of India and Honorary Patron of PMA, India. It had a representation at the Secretary level of seven Central Government Ministries, head of three major Business Associations CII, FICCI and ASSOCHAM and Chairman & CEO’s of both Private and Public Sector companies. Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Deputy Chairman of Planning Commission emphasized the importance of project management for emerging economies like India. He stressed that there cannot be any room for slippages in time and overruns in cost. He also compared the total number of certified project professionals being far more in China than in India, specially at the higher levels of IPMA Certification like A, B and C. He further stated that like the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), that reports to the President of USA and is the catalyst for promoting project Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Hon’ble Dy. Chairman, Planning Commission, giving the Inaugural Address. management extensively in the government, Planning Commission should also take a lead in a similar way in promoting project management in the government. The GS 2009 was attended by over 450 participants from all over the world. -

Dr. Atwal by : INVC Team Published on : 26 Mar, 2016 03:33 PM IST

Sikhs always uphold the supreme values of humanity : Dr. Atwal By : INVC Team Published On : 26 Mar, 2016 03:33 PM IST INVC NEWS Cahandigarh, The freedom of India was hard earned by the supreme sacrifices made by the freedom fighters and Gadris. Though the Indian are now enjoying the virtues of freedom but unfortunately they have badly failed in upholding the values and legacy of their martyrs. This was disclosed by Dr. Charanjit singh Atwal Speaker of Punjab Assembly in ‘Second Lahore conspiracy case centenary function’ organized by India Chapter of Haridarshan Memorial International Trust Canada at Chandigarh Museum and Art Gallery. Dr. Atwal showered high praise upon the Haridarshan Memorial International Trust for organizing ‘Second Lahore conspiracy case centenary function’ at Chandigarh to remembering the freedom fighters of Gadar movement for their contributions in the freedom struggle of India, so that the new generation can take inspiration from the great sacrifices of our forefathers. He further said that Punjabis are brave heart fighters who always fight for their rights. He said that the new generation should follow the footsteps of their fore fathers so that Punjab could advance to newer heights. Mr Tarlochan Singh former MP and ex Chairman of Minorities Commission of Union Government in his presidential address on the occasion said Punjabis especially Sikhs are always on fore front of every movement for the welfare of the people of India, But their contribution has not been adequately recognized by the Indian Govt. he further said the Sikhs always uphold the supreme values of humanity and work on the principle of ‘sarbat Da Bhalla’. -

Sachin Tendulkar

“Today’s Accomplishments Were Yesterday’s Impossibilities.” April 25, 2021 –– Robert H. Schuller [email protected] 3 THE FACT CORNER BRAIN TEASERS English Proverbs and Meanings 1 Q. Which word does NOT belong with the others? * Every man for himself. something you will find away. others? A. heading B. body You must think of your own A. parsley B. basil C. letter D. closing interests before the interests of * If you chase two rabbits, you C. dill D. mayonnaise others. will not catch either one. 5 Q. Which word does NOT belong with the If you try to do two things at 2 Q. Which word does NOT belong with the others? * He who hesitates is lost. the same time, you won't others? A. tape B. twine If you delay your decision too succeed in doing either of A. tulip B. rose C. cord D. yarn long, you may miss a good them. C. bud D. daisy opportunity. 6 Q. Odometer is to mileage as compass is to * Lightning never strikes in the 3 Q. Which word does NOT belong with the A. speed B. hiking * He who plays with fire gets same place twice. others? C. needle D. direction burnt. An unusual event is not likely A. guitar B. flute If you behave in a risky way, to occur again in exactly the C. violin D. cello 7 Q. Marathon is to race as hibernation is to you are likely to have same circumstances. A. winter B. bear problems. 4 Q. Which word does NOT belong with the C. -

Page 1 of 7 India | Freedom House 3/4/2015

India | Freedom House Page 1 of 7 India freedomhouse.org India held parliamentary (Lok Sabha) elections in nine phases from April 7 to May 12, 2014, with a turnout of some 554 million voters, or 66 percent. Narendra Modi, a three-term chief minister from the western state of Gujarat, led his right-leaning Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its National Democratic Alliance (NDA) coalition to a decisive victory over the ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA), headed by Congress Party standard-bearer Rahul Gandhi. The BJP’s success marked the first time a single party won a majority of seats in the Lok Sabha since 1984. Modi formed a government as prime minister on May 26. Modi had been a controversial figure due to his performance as chief minister during the 2002 Gujarat riots, in which more than 1,000 Muslims were killed. A Hindu nationalist, he was accused of complicity in the bloodshed, and some feared communal violence during the 2014 election campaign. There was evidence of a BJP strategy of communal polarization in Uttar Pradesh and Assam states in 2013 and 2014, respectively; divisive speeches by politicians including Modi and his Uttar Pradesh campaign chief Amit Shah, who was promoted to national BJP party president after the elections, were blamed for fueling or capitalizing on deadly communal clashes. Also during the year, censorship of books and social media was a growing concern. Political Rights and Civil Liberties: Political Rights: 35 / 40 (+1) [Key] A. Electoral Process: 12 / 12 (+1) Under the supervision of the Election Commission of India, elections have generally been free and fair. -

Current Affairs and Answer Sheet

Current Affairs India 1. In July 2018, Haryana Chief Minister Manohar Lal Khattar launched a campaign called “Paudhagir”. The aim was to increase the green cover of the state. 2. On July 17th, 2018, IIT Delhi signed an agreement with All India Institute of Ayurveda (AIIA) to launch projects to give scientific validation to the ancient medical science of Ayurveda and integrate it with technology. 3. Tata Consultancy Services (TCS) announced its partnership with a French energy company “Total” to develop a digital innovation centre in India. 4. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) would issue new Rs. 100 note with motif of ‘Rani Ki Vav’ in 2018. The base colour of the note is lavender. 5. Indian Government has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with United Kingdom to obtain help in enhancing overall public transport system in India. The MoU was signed by the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways, India, and Transport for London (TFL) to develop public transport in India. 6. According to Travel + Leisure’s World’s Best Cities report, the city of Udaipur was ranked 3rd among the 15 of the world’s best cities. The top 2 cities are both in Mexico–San Miguel de Allende and Oaxaca. 7. In July 2018, Indian Government announced the launch of a new MicroDot Technology that would help check on vehicle thefts. 8. National School of Drama (NSD) will be hosting the 8th edition of Theatre Olympics in Mumbai this is the first time India is hosting the festival from 24th March 2018 to 7th April 2018. -

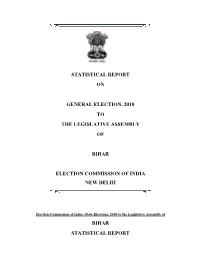

Statistical Report on General Election, 2010 To

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 2010 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF BIHAR ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India- State Elections, 2010 to the Legislative Assembly of BIHAR STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENT Sl. No. Subject Page No. 1 List of Participating Political Parties and 1-3 Abbreviations 2 Other Abbreviations in the Report 4 3 Highlights 5 4 List of Successful Candidates 6-12 5 Performance of Political Parties 13-16 6 Candidates Data Summary 17 7 Electors Data Summary 18 8 Female Candidates 19-30 9 Constituency Data Summary 31-273 10 Detailed Result 274-391 Election Commission of India- State Election, 2010 to the Legislative Assembly Of Bihar LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTY TYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJP Bharatiya Janata Party 2 . BSP Bahujan Samaj Party 3 . CPI Communist Party of India 4 . CPM Communist Party of India (Marxist) 5 . INC Indian National Congress 6 . NCP Nationalist Congress Party STATE PARTIES 7 . JD(U) Janata Dal (United) 8 . LJP Lok Jan Shakti Party 9 . RJD Rashtriya Janata Dal STATE PARTIES - OTHER STATES 10 . AIFB All India Forward Bloc 11 . JD(S) Janata Dal (Secular) 12 . JKNPP Jammu & Kashmir National Panthers Party 13 . JMM Jharkhand Mukti Morcha 14 . JVM Jharkhand Vikas Morcha (Prajatantrik) 15 . MUL Muslim League Kerala State Committee 16 . RSP Revolutionary Socialist Party 17 . SHS Shivsena 18 . SP Samajwadi Party REGISTERED(Unrecognised) PARTIES 19 . ABAPSMP AKHIL BHARTIYA ATYANT PICHARA SANGHARSH MORCHA PARTY 20 . ABAS Akhil Bharatiya Ashok Sena 21 . ABDBM Akhil Bharatiya Desh Bhakt Morcha 22 . ABHKP Akhil Bharatiya Hind Kranti Party 23 .