Chapter I Nineteenth Century Princely State of Kolhapur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RESUME (A) Personal Information: Full Name: Dr

RESUME (A) Personal Information: Full Name: Dr. (Smt) Megha Nandkishor Mole Date of birth: 27/08/1987 Qualification: M. Sc., Ph.D. Mobile:- 9975513667 B) EDUCATIONAL QUALIFICATION: Board/ Year of Degree Subject Percentage Class University Passing Shivaji Botany Ph. D University, (Marine 2014 B Second Kolhapur Botany) Shivaji Botany (Plant M. Sc. University, 2009 63.08 First Biotechnology) Kolhapur Shivaji B. Sc. University, Botany 2007 First 65.08 Kolhapur Physics, Kolhapur H.S.C. Chemistry, 2004 54.67 Second Board Biology. Kolhapur All S.S.C. 2002 First Board Compulsory 60.40 Other Courses: Examination Year Marks (%) MH-CIT July- 2007 78 Marathi Type writing Sep. - 2010 88 1 | P a g e Ph. D.: Title :“Antimicrobial, Antioxidant and haemolytic activiy of seaweeds from Sindhudurg district of Maharashtra.” Guide : Prof. Dr. (Smt.) A. B. Sabale Institute : Department of Botany, Shivaji University, Kolhapur– 416 004 (MS) INDIA. EXPERIENCE SUMMARY: (Starting With Recent) 1) Currently working as senior college lecturer in Botany, at Rajaram College, Kolhapur 2) Worked as a senior college Lecturer in Botany, at Rajaram college, Kolhapur from 7st July 2016 to 31 march 2017. 3) Worked as a senior college Lecturer in Botany, at Rajaram college, Kolhapur from 1st August 2015 to 31 march 2016. 2) Worked as a senior college Lecturer in Botany, at Rajaram College, Kolhapur from 21st December 2010 to 31st March 2011. 3) Worked as senior college Lecturer in Botany, at Rajaram College, Kolhapur from 27th August 2012 to 31st March 2013. (B) Research Contribution (From 2010 to 2015) i) Research papers published: Sr Author Title Journal Publicatio Status ISSN IF Peer no n Revi ewed 1. -

College / Organisation ROHANT SIDDHARAM DHABBE JCJ Sachinkumar R

Full name Name of the institute/ college / organisation ROHANT SIDDHARAM DHABBE JCJ Sachinkumar R. Patil Jaysingpur College Jaysingpur Sheetal Dattatray Londhe Willingdon college Sangli KRISHNA MAHAVIDYALAYA, RETHARE BK., SAMPATRAO SHIVAJIRAO PATIL KARAD Dr.Tushar Ganpatrao Ghatage Jaysingpur College, Jaysingpur Lata Parasharam Bhopale Rajaram college Kolhapur Jyoti Ashok Chavan Rajaram College Kolhapur Rajaram Santram Sawant Dr. Ghali College, Gadhinglaj Prof.Neeta Vijayrao Jagtap P.D.E.A's Waghire College sas Srichand Parsram Hinduja Sree Narayana Guru College of Commerce Dr Anil N Dadas Dahiwadi College SAHYADRI SHIKSHAN SEVA MANDAL'S ARTS AND Rima Deepak Gharat COMMERCE COLLEGE Payal Hinduja St. Paul Degree College MSS'S ARTS, SCIENCE & COMMERCE COLLEGE, SHARAD KHANDU KHOJE AMBAD DIST.JALNA Sakharam Damu Aghav B. G. College, Sangvi Pandhare Balasaheb Dashrath New Law College Ahmednagar Swapnil Vasantrao Sonje Dr.D.Y.Patil College of Physiotherapy, Pune Ajeet Singh Sanatan Dharma College, Ambala Cantt. Dadasaheb Dhanaji Nana Chaudhari Social Work College, Ravindra Amrut Patil Malkapur, Dist. Buldana Comrade Godavari Shamrao Parulekar College of Arts VILAS VASANT RAYMALE Commerce and Science Talasari Swati Sarwate St. Mira's college for girls Koregaon park Pune Swapneel Dipchand Agarwal Sadguru Gadage Maharaj College, Karad Sandhya Jaysing Mane Chandrabai Shantappa Shendure College Hupari Dattatraya Ramchandra Bhosale Chandrabai-Shantappa Shendure College, Hupari Pritam Raygonda Patil Jaysingpur College,Jaysingput. Sandip Jotiram Kirdat Chhatrapati Shivaji College Satara (Autonomous) Sarika Vishwas More Chandrabai Shanttappa Shendure College, Hupari Jayvant Balavant Patade Jaysingpur College, Jaysingpur Prajakta Pramod Rajmane Bharati Vidyapeeth college of Engineering ,Kolhapur Suraj Ashok Sonawane Rajaram College Kolhapur Aishwarya Prasad Otari S.M.Joshi College, Hadapsar Dr. -

Staff Profile : Dr. Mrs. K. K. Patil

Staff Profile : Dr. Mrs. K. K. Patil Resume Name Dr. Mrs. Kranti K. Patil Designation Associate Professor, Chemistry Department, Rajaram College, Kolhapur- 416004 Address 381-A/3, Chaitany, Katkar Mal, near Radhabai Shinde HIghSchool, Kolhapur E-mail [email protected] Mobile 9421290200 Telephone No 0231-2520200 Academic Qualification Name of Board /Univ awarding Certi. / Year of Sr Examination % Division/ /Grade Degree Passing First Class with 1 S.S.C. SSC Board Pune. 1987 88.71 dist First Class with 2 H.S.C. HSC Board Pune. 1989 78.17 dist First Class with 3 B.Sc. Shivaji University, Kolhpaur. 1992 82 dist 1st with 4 M.Sc. (Organic Chemistry) Shivaji University, Kolhpaur. 1994 71.5 Distinction 5 SET Pune University [as State Agency] 1995 - pass Other degrees, Dip-loma if Maharashtra State Technical Board, 6 2003 - pass any Mumbai. 7 Ph. D. (Chemistry) Shivaji University, Kolhapur. 11/ 11/2005 - - Title of the Research Degree Date of Degrees Title University award Ph. D. Kinetics And Mechanism Of Oxidations by Shivaji University, 11/11/2005 (Chemistry) Oxone Kolhapur Positions Held 1. Posts held in Government Service Sr Designation From Grade 1 Lecturer 29/7/1995 2200-4000(Ad-hoc basis) 2 Lecturer-regularisation 20/4/2002 शा.िन. SCP1001/( 204/01)/ M.S.-2 दनांक 20/4/2002 3 Lecturer – senior scale 5/5/2003 10000-15200/- 4 Lecturer – Selection Grade (AGP 8000) 5/5/2008 15600-37400/ -(AGP 8000) 5 Associate Professor (AGP 9000) 5/5/2011 37400/ -67000/-(AGP 9000) Total Experience in Govt College: 22 Years Research Activities Students awarded Research Degree: 01 Sr. -

Dr.-Rahul-Gajanan-Kamble.Pdf

Curriculum Vitae Personal Information Name : Dr. Rahul Gajanan Kamble Date of Birth : 24th July, 1988 Sex : Male Marital Status : Married Address : Kamanves near School No 5 Miraj, Tal- Miraj Dist- Sangli Language Known : English, Marathi, Hindi. Email ID : [email protected], [email protected] , [email protected] Qualification : M.A. (Clinical Psychology) SET., PhD. Designation : Head and Assistant Professor Institute : Department of Psychology, Bhogawati Mahavidyalay Kurukali, Kolhapur. Academic Qualifications Exam Board/University Passing Year Percentage Grade B.A Shivaji University Kolhapur April 2008 53.78 B+ M.A Shivaji University Kolhapur April 2010 69.25 First Class 27th November SET Pune University Pune ….. ….. 2011 Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar PhD. 04th March, 2017 ….. ….. Marthwad University Aurangabad Other Qualifications: Passing Percentag Course Name Board/University Grade Year e Shivaji University Certificate Course In Criminal Psychology May 2009 59.33 B+ Kolhapur Shivaji University First Diploma Course In Criminal Psychology May 2010 69.00 Kolhapur Class Advanced Diploma In Criminal Shivaji University First June 2011 62.33 Psychology Kolhapur Class Maharashtra State English Typewriting Council of Examination, Nov 2009 64/100 B Pune Maharashtra State Board MSCIT of Technical Education, July 2007 60/100 B+ Mumbai 1 Academic Details Teaching Experience: 1. C.H.B. Lecturer 2 Years Department of Psychology COC in Criminal Psychology Smt. Kasturbai Walchand College (Arts and Science), Sangli 416 416 Maharashtra. Phone No. (Office): 0233-2372102 Asst. Professor 1 year 2. Government Institute of Forensic Science Aurangabad 431001, Maharashtra, Phone (office): 2040 - 2400219 Research and Academic Development Participation : Workshops Sr. Workshops Place Date Level No Rural Problems in Psychology – A D.R. -

B.Sc.-Regular-B.Sc.-June2010-Sem(No Branch) for Mar-2017

Shivaji University, Kolhapur http://suk.digitaluniversity.ac/ Vidyanagar , Kolhapur-416004, Maharashtra(India) Merit List B.Sc.-Regular-B.Sc.-June2010-Sem(No Branch) for Mar-2017 Selected criteria for Merit list generation Template Name: T Y B.Sc Merit_List Configuration Done By: sbkamat on 13 Jun 2017 12:06 PM Merit List Generated By: sbkamat on 04 Jul 2017 11:38 AM Include Grand Total: Course Include Gender: Male,Female Include Category: ALL Include Physically Handicap: No Include Ordinance: No Include Ordinance Mark: No Attempts: Less than equal to 1 CuttOff: 60 Include Classes: First Class with Distinction,First Class Include Additional Passing Heads: No Papers: No Shivaji University, Kolhapur http://suk.digitaluniversity.ac/ Vidyanagar , Kolhapur-416004, Maharashtra(India) Merit List B.Sc.-Regular-B.Sc.-June2010-Sem(No Branch) for Mar-2017 Template Name: T Y B.Sc Merit_List Sr. Merit Name of Student Gender Marks Percentage College Name PRN Seat Number No. No. Obtained (Code) 1 1 CHIKHALAGE SUSHANT Male 2383/2500 95.32 Dattajirao Kadam 2014015500809761 219563 VISHWAS Arts, Science and Address Commerce LIGADE MALA ICH College(38) City : ICHALKARANJI Taluka : Hatkanangale Distict : Kolhapur State : Maharashtra Pin : 416115 Mobile Number : Not Available Email ID : Not Available 2 2 PATIL KANCHAN SURESH Female 2358/2500 94.32 The New College(30) 2014015500858037 218367 Address PLOT NO 27 787/3 B WARD RAMANANDANAGAR KOLHAPUR City : KOLHAPUR Taluka : Karveer Distict : Kolhapur State : Maharashtra Pin : 416007 Mobile Number : 919423752131 -

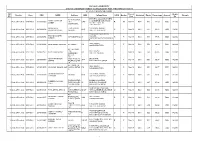

Final Electoral Roll SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR for The

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Final Electoral Roll For the Election of Board of Studies under section 40(2)(c) of the Maharashatra Public Universirties Act,2016 Polling Center : - 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur BOARD OF STUDIES IN ACCOUNTANCY 1 CHOUGALE PRAVEEN NARAYAN D.R. Mane Mahavidyalaya,Kagal 2 MANE VIJAY ANNASO Chandrabai-Shantappa Shendure College, Hupari,Hupari Page No.- 1 SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Final Electoral Roll For the Election of Board of Studies under section 40(2)(c) of the Maharashatra Public Universirties Act,2016 Polling Center : - 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur BOARD OF STUDIES IN BIOCHEMISTRY AND BIOTECHNOLOGY 3 ATTAR YASMIN CHAND Rajaram College,Kolhapur 4 SANANDAM MONICA RAJAN Kits College Of Engineering,Kolhapur Page No.- 2 SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Final Electoral Roll For the Election of Board of Studies under section 40(2)(c) of the Maharashatra Public Universirties Act,2016 Polling Center : - 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur BOARD OF STUDIES IN BOTANY 5 KHILARE CHANDRAKANT JAGANNATH Rajarshi Chh. Shahu College,Kolhapur 6 TORO SUNITA VISHNU Rajaram College,Kolhapur Page No.- 3 SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Final Electoral Roll For the Election of Board of Studies under section 40(2)(c) of the Maharashatra Public Universirties Act,2016 Polling Center : - 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur BOARD OF STUDIES IN BUSINESS ECONOMICS 7 JADHAV SUBHASH ATMARAM D.R. Mane Mahavidyalaya,Kagal 8 KATHARE HANAMANT NANA Rajaram College,Kolhapur Page No.- 4 SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY, KOLHAPUR Final Electoral Roll For the Election of Board of Studies under section 40(2)(c) of the Maharashatra Public Universirties Act,2016 Polling Center : - 1 Kolhapur District - Chh.Shahu Central Institute of Business Education & Research, Kolhapur BOARD OF STUDIES IN CHEMISTRY AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING 9 MANE S.G. -

GIPE-007204.Pdf (7.573Mb)

His Excellency the IUght Hon. Edward Frederick Lindley Wood , Baron Irwin of Kirby Underdale, G.M.S.l., G.M.I.E., Viceroy and Governor-General of India. NOTES ON KOLHAPUR Her Excellency Lady Irwin. NOTES ON KOLHAPUR BY RAO BAHADUR SIR R. V. SABNIS U.OIWAJC OP II'.OI.HAIUI. BOYB.\Y THE TI:UES PRESS 1928 CONTENTS PART I PAGI Situation and Aspect .. I Early History 3 Mauryu ... 3 Andhras 4 Chalukyas •• .5 Yadavu •• .. 6 Dahamanis .. 6 Marathas: Shivaji the Great, 1674 to r68o 7 Sambhaji •• .. 8 Rajaram •• 9 Shlvaji n. lj'OO to I7U •• 9 Sambhaji II. 1712 to 176o .•• 9 Shivaji III. 176o to r8u •• IO Shambhu. 18u to r8u: •• •• II Shahaj~ 18zr to 1837 n Shivaji IV, 1837 to t866 •• • • 11 Rajaram II, 1866 to 1870 u Shivaji V, 1870 to 1883 •• u Shahu II, 187-4 to 1921 and Minority period 13 Rajaram Ill •• •• 2S viii CONTENTS. PART II. PAGE Amba Bai Temple .. 39 Ceiling of Navagraha-:Mandap or Ashta-dikpal temple 4t Vitoba Temple • • 44 Tryrnbu1i • • • • 45 The Memorial Temples •• .. 49 Temple of Kopeshwar (Khidrapore) .. 50 Royal family of England ·• 53A New Palace .. 54 Old Palace •• .. 55 Residency •• • • '57 Shri Radhabai Akka Sahib Maharaj buildings .. 58 The Town Hall .. 59 Raj aram College •• •• 6o Kolhapur General Library · .. 6:a Ahilya Bai Girls' School .. 64 Jayshing Rao Ghatge Technical School .. 67 Albert Edward Hospital .. 6g Her Highness Shri Vijayamala Veterinary Hospital.. 7I Rajput Wadi Paddock • • • • 72 Shri Shahu Chhatrapati Spinning and Weaving Mills. 74 Sir Leslie Wilson Road and Lady Wilson Bridge • . 76 Shri Rajaram Tank 78 Panch Ganga Pumping Installation . -

142 Tourism Resources and Sustainable

I J R S S I S, Vol. V (1), Jan 2017: 142-148 ISSN 2347 – 8268 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RESEARCHES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES AND INFORMATION STUDIES © VISHWASHANTI MULTIPURPOSE SOCIETY (Global Peace Multipurpose Society) R. No. MH-659/13(N) www.vmsindia.org TOURISM RESOURCES AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM IN KOLHAPUR DISTRICT: A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS Shubhangi S. Kale and Sambhaji D. Shinde P.D.V.P. Mahavidyalaya, Shivaji University, Tasgaon, Dist. Sangli Kolhapur Abstract Tourism is an e ver growing se rvice industry with underlying immense potential growth. It is an ancient phenomenon which has been exists in social communities since long back. Present day it has become a social and economical phenomenon. Kolhapur is one of the leading tourist district can be develop in the state of Maharashtra (India). Healthy atmosphe re of the Kolhapur district located at South Western part of Maharashtra attracts tourists from all corne rs of the country, in the present pape r an attempt has been made to classify tourist destinations in Kolhapur district, for that are assessing present status and classification of tourism. Stress is also given on untapped classification of tourism as an industry. It is obse rved that there are lots of tourist’s attractions in and around the district of Kolhapur. Similarly the district of Kolhapur is enriched with a rich biodiversity making it one of the 35 biodiversity hotspots in the world. It is observed that there are lots of tourist’s attractions in and around the district of Kolhapur. Keywords : Observations, Tourist Destinations, Physiographical Setup, Classification and Tourism Potential Growth. -

SHIVAJI UNIVERSIT MERIT SCHOLARSHIP Excel Sheet.Xlsx

SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY SHIVAJI UNIVERSITY MERIT SCHOLARSHIP FOR THE YEAR 2018-2019 ELIGIBEL STUDENS CHART SR Passed Cheque Faculty Class PRN NAME Address ABB College Name U/R/S Gender Addmited Marks Persentage Amount Remark NO Year No SHIVARAJ COLLAGE OF ARTS A/P BHADGAON, SHINDE BHAVESH & COMMERCE &D.S.KADAM 1 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018065656 TAL - GAD R M Mar-18 BA I 583 89.69 5000 142380 SUJEET SCIENCE COLLEGE GADHINGLAJ. ,GADHIINGLAG SINHA AMITA H-456, KASBA D.D.SHINDE SARKAR 2 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018028682 DDS R F Mar-18 BA I 575 88.46 5000 142381 ANIRUDHPRASAD BAVADA. COLLEGE,KOLHAPUR YESHWANTRAO CHAVAN KHOT SANJASHRI WARANA 3 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018026874 A/P AMBAPWADI W R F Mar-18 BA I 568 87.38 5000 142382 SURESH MAHAVIDYALAYA,WARNANAGA R CHH. SHIVAJI 4 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018030263 KALE MONALI RAMDAS A/P VADUJ CH U F Mar-18 BA I 559 86.00 5000 142383 COLLEGE,SATARA. A/P TARGAON ,TAL CHH. SHIVAJI 5 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018027527 BHISE ANKITA ANIL CH R F Mar-18 BA I 558 85.85 5000 142384 KOREGAON, COLLEGE,SATARA. SATARA A/P ADAVKAR MAYURI MUMEWADI,TAL DR.J.P.NAIK 6 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018088089 JPN R F Mar-18 BA I 555 85.38 5000 142385 GUNDU AAJRA,KOLHAP MAHAVIDYALAY,UTTUR. UR A/P ENKUL,TAL CHH. SHIVAJI 7 Arts & Fine Arts 12TH BA I 2018029530 MUJAWAR SALONI SAIF KHATAV,SATAR CH R F Mar-18 BA I 551 84.77 5000 142386 COLLEGE,SATARA. -

Circular Regarding M.Phil Ph.D and New Guide List.Pdf

Shivaji University, Kolhapur. Subjectwise list of Research Guide (update 15/6/2018) Subject Approval of Sr. No. Name of Teacher and College Research Guide Dr. Dadas Anil Nirutti, English M.Phil., Ph.D. 1 Dahiwadi College, Dahiwadi. Dr. Dixit Sanjaykumar Ganpat. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 2 Mudhoji College, Phaltan Dr. Gangatirkar Kalpana Girish. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 3 Mahavir Mahavidyalaya, Kolhapur. Dr. Gharge Sunita Sunil. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 4 Chh. Shivaji College, Satara Dr. Gore Pandurang Narayan. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 5 Smt. Kasturbai Walchand College of Arts & Science, Sangli Dr. Ingale Gangubai / Shashikala English M.Phil., Ph.D. 6 Dhanapal, Devchand College, Arjunnagar. Dr. Jadhav Arun Murlidhar. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 7 Yashwantrao Chavan Arts & Commerce College, Urun-Islampur. Dr. Jarali Irappa Ramu English Ph.D 8 Yashwantrao Chavan College. Dr. Khavare Namdev Pandurang English Ph.D 9 Hon.Shri Annasaheb Arts, Commerce & Science College, Hatkangle. Dr. Lokde Bhagwan Shankar, English M.Phil., Ph.D. 10 D.P. Bhosale College, Koregaon Dr. Rode Sonali Vijay, English M.Phil., Ph.D. 11 Rajarambapu College, Kolhapur. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 12 Dr. Shinde Narayan Kashinath. M.H. Shinde Mahavidyalaya, Tisangi. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 13 Dr. Tathe Ujjvala Nivritti, Mahila Mahavidyalaya, Dr. Waghmare Balkrishna Dada. English M.Phil., Ph.D. 14 Kranti Agrani G.D. Bapu Lad, Arts Mahavidyalaya,Kundal Dr. Ballal Anand Shamrao, Marathi M.Phil., Ph.D. 15 Ajara Mahavidyalaya, Ajara. Create PDF files without this message by purchasing novaPDF printer (http://www.novapdf.com) Dr. Chavan Yashwant Maruti, Marathi M.Phil., Ph.D. -

Admission Process Centerwise College Details for Spot Admission Round

Appendix 'K' Admission Process Centerwise College details for Spot Admission Round Sr. Admission Colleges under Admission Process Center No. Process Center College of Agriculture, 1. College of Agriculture, Shivajinagar, Pune 411 005. 1. Shivajinagar, Pune 411 2. Padmashree Dr. Appasaheb Pawar College of Agriculture, Baramati 005. At.Post. Shardanagar, Tal. Baramati, Dist.Pune 413 115. 3. College of Agriculture, Akluj Tal.Malshiras Dist.Solapur-413101. 4. Padmabhushan Vasant Dada Patil College of Agriculture, Ambi, Talegaon Dabhade, Tal. Maval Dist. Pune 410506. 5. Lokmangal College of Agriculture, At. Post. Wadala, Tal. Uttar Solapur Dist.Solapur 413222. 6. College of Agriculture, At. Post.Paniv Tal. Malshiras, Dist.Solapur 413113. College of Agriculture, 7. College of Agriculture, Old Pune Benglore Road, Rajaram College 2. Old Pune Benglore Near Shivaji University, Vidyanagar, Kolhapur, Tal. Karveer, Dist. Road, Rajaram College Kolhapur 416004. Near Shivaji 8. Yashwantrao Chavan College of Agriculture, Post Box No.80, Karad, University, Dist. Satara 415110 Vidyanagar, Kolhapur, Tal. Karveer, 9. Loknete Mohanrao Kadam College of Agriculture, Sonsal Dist. Kolhapur 416004. Hingangaon, Tal.Kadegaon Dist.Sangli 415303. 10. College of Agriculture, Rajmachi, Tal. Karad Dist. Satara 415 110. 11. College of Agriculture, Near Jinti Naka, Pune Road,At Post, Phaltan, Tal.Phaltan, Dist. Satara 415523 12. College of Agriculture, At Post. Talsande, Tal. Hatkangale Dist . Kolhapur 416112. 13. Sharad College of Agriculture, Jainapur, Tal. Shirol, Dist. Kolhapur 416101. 14. Roshanji Shamanji College of Agriculture, Nesari Tal. Gadhinglaj Dist. Kolhapur 15. Jaywantrao Bhosale Krishna College of Agriculture, Rethare Post- Shivnagar, Tal..Karad Dist.Satara 415 108. College of Agriculture, 16. College of Agriculture, Parola Road, Dhule 424 104. -

Dattajirao Kadam Arts, Science and Commerce College, Ichalkaranji

―Dissemination of Education for Knowledge, Science and Culture.‖ – Shikshanmaharshi Dr. Bapuji Salunkhe Shri Swami Vivekanand Shikshan Sanstha‘s, Dattajirao Kadam Arts, Science and Commerce College, Ichalkaranji. For rd NAAC - 3 Cycle Submitted to National Assessment & Accreditation Council (NAAC) Bengaluru MARCH 2017 SELF-STUDY REPORT: 3rd CYCLE OF ACCREDITATION Vision Statement Dattajirao Kadam Arts, Science and Commerce College, Ichalkaranji will provide excellent educational opportunities that are responsive to the needs of the community and help students meet economic, social, and environmental challenges to become active participants in shaping the world of the future. Mission “Dissemination of education for knowledge, science and culture.” Objectives Meeting community and students needs by creating an educational environment and culture so students can attain a variety of goals. To maintain a high standard of integrity and performance leading to the achievement of academic and professional goals. Imparting quality education for achieving overall personality development of youth. Education to inculcate scientific temperament. Education to inculcate cultural values into students and to make them better citizens. To ensure values like truth, honesty, character, sacrifice, curbing social exploitation through education. To aim at overall personality development through extracurricular activities. To provide opportunities to students to enhance their skills, potential, social responsibilities, sportsman spirit through NCC, NSS, sports, cultural activities, career oriented courses. Enabling students to face challenges of ever changing modern world and to contribute to it in meaningful way. To help the students for on-the-job training and placements. DATTAJIRAO KADAM ARTS, SCIENCE AND COMMERCE COLLEGE, ICHALKARANJI SELF-STUDY REPORT: 3rd CYCLE OF ACCREDITATION Academic Programmes Degree Programmes at Under Graduate Level Programmes at Post Graduate Level B.A.