The Best Medicine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anarchy No.6

V The ZERO DE CONDUITE Anarchism of Jean Vigo Jean Vigo The innocent eye of Robert Flaherty The tragic eye of Luis Buntiel Two experimental films discussed by their makers L'ATALANTE ANARCHY & CINEMA 1s6d USA 25 cents ANARCHY6 A JOURNAL OF ANARCHIST IDEAS I6l Contents of No. 6 August 1961 When Shirley Clarke made her screen version of The Connection in future for A the cinema? Ward Jackson 161 New York a few months ago, she financed the production by methods The anarchism of Jean Vigo John Ellerby 163 familiar in (he theatre but almost untested in the cinema. A couple of hundred small investors took shares in the enterprise; they were given no Making 'Circus at Clopton Hall' Annie Mygind 174 Huarantee that they would ever see their money again, and there was no The animated film grows up Philip Sansom 179 advance commitment to a distributor. John Cassavetes' Shadows was only Making 'The Little Island' Dick Williams 181 lompleted after money had been raised through a broadcast appeal. Lionel Rotfosin went into the business of running a cinema to ensure that LuisBufiuel: reality and illusion Rufus Segar 183 On Ilia Howcry and Come Back, Africa got a showing in New York. In Another look at Bufiuel Tristram Shandy 186 brume, sttme young directors have been able to finance their films out of legacies, money lent or given by parents or friends. je innocent eye of Robert Flaherty C. 190 Nothing like this has yet happened in England—nor does it seem very wings by : Rufus Segar, Dick Williams and Denis Lowson. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

PDF (142.67 Kib)

At the Crossroads of Jim Donnelly Metal Music West Coast News and Comedy By Justine Taormino ’06 By Peter Gordon ’78 Northern California alumni are abuzz At the improbable intersection of Brendon Small ’97 with news of their work in a variety metal music, animated TV, and stand- of areas. Here are some recent high- up comedy, the story of guitarist, com- lights. poser, actor, and producer Brendon sitcom that aired from 1999 to 2004. Benjamin Flint ’85 of Oakland led Small ’97 stands apart. Metal fans Although he also provided the show’s two Diablo Valley College jazz choirs worldwide know him as the creative music, he rapidly became better Reno Jazz Festival where they took first mastermind behind the smash-hit ani- known as a comedian. and third places in their division. Flint mated TV show Metalocalypse and the Toward the end of the show’s run, also directs the Oakland Jazz Choir and metal bands Dethklok and Galaktikon. Small began to turn back to the guitar. has taught at Jazz Camp West. Small’s unique journey began in “I was so excited to hear what people This fall, saxophonist Sonya the laid-back northern California town were doing in metal,” he says. “They Jason ’85 of Montara, will release of Salinas, where he remembers spend- were actually playing their instruments Feels So Good: Live in Half Moon Bay, ing long hours practicing guitar and incredibly well! I now had the comedy her fourth solo album. Recorded live re-watching VHS copies of his favorite chops and could write, thanks to Home at the legendary jazz venue Bach comedies. -

B4 the MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 6:30 7:30 8:30 9:30

B4 B4 THE MESSENGER, Friday, March 9, 2012 03/9 6AM 6:30 7AM 7:30 8AM 8:30 9AM 9:30 10AM 10:30 11AM 11:30 WBKO ^ 5:30 AM Kentucky (N) Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å WBKO at Midday (N) % Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å The 700 Club (N) Å WHAG News at 12:00PM (N) _ _ Paid Program Storm Stories Å Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Local 7 News Lifestyles Family Feud Å Family Feud Å Animal Adv Å Swift Justice Å Judge Mathis Å 3 ( 5:00 The Daily Buzz Å Better (N) Å Cash Cab Å Cash Cab Å The Cosby Show Å The Cosby Show Å Law & Order: Criminal Intent Å C ) 5:00 QVC This Morning Perricone MD Cosmeceuticals Kitchen Innovations LizClaiborne New York Fashion. Q Check Style Edition . * 14 News Sunrise (N) Å Today Kathy Bates; Elizabeth Olsen. (N) Å Today (N) Å Today (N) Å :15 Midday With Mike (N) Å 9 + 5:00 Eyewitness News Daybreak (N) Å Good Morning America Andrew Garfield; Richard Blais. (N) Å Live! With Kelly (N) Å The View (N) Å FreeCruise Paid Program ) , Arthur (EI) Å Martha Speaks Å Curious George Å Cat in the Hat Å Super Why! Å Dinosaur Train Å Sesame Street (EI) Å Sid the Science Å WordWorld (EI) Å Super Why! Å Barney & Friends Å L ` Morning News Å Morning News Å CBS This Morning Ewan McGregor; Grant Hill. (N) Å The Doctors (N) Å The Price Is Right (N) Å The Young and the Restless (N) Å & 2 BBC World News Å Kentucky Health Å Body Electric Å TV 411 Å GED Connection Å GED Connection Å Paint This-Jerry Å Quilt in a Day Å Knitting Daily Å Beads, Baubles Å Charlie Rose Å WGN / Paid Program Paid Program Bewitched Å Dream of Jeannie Å Matlock “The Ghost” Å Matlock “The Class” Å In the Heat of the Night “Discovery” Å In the Heat of the Night Å INSP 1 Int’nl Fellowship Life Today Å Creflo Dollar Å Feed the Children Victory Today Life Today Å Joseph Prince Å Joyce Meyer Å Humanitarian Int’nl Fellowship The Waltons “The Idol” TBN 5 Spring Praise-A-Thon Spring Praise-A-Thon HGTV 7 Destination De Marriage/Const. -

H Jon Benjamin on Getting Noticed

H Jon Benjamin On Getting Noticed Patin universalizing double-quick? Accordant and erect Cyril tag while scarred Billie even her Madison creepingly and chelated cross-legged. Permitted Lonnie never noising so seemingly or barber any purlers insuperably. Rebecca romjin is getting a sliding scale. Drank with my buddies and watched the Maniac episode of Always Sunny. We are happily again is cоnnеctеd to increase property in front door until i noticed your notice will likely to each? 25 Best H Jon Benjamin Memes Benjamins Memes Alan. The brain Game Screenshot Thread or HEAVY. Expect you on dvd show lazy loaded on everyone still need for your business? For review it say like getting as the wheel just a Porsche. Just wanted rid of something dead ends 0 replies 0 retweets 0 likes. Should you good making plans for going children the law enforcement officials, I guess. H Jon Benjamin Wet Hot American what I describe like jump time come watch. Do not have starring you meet the h jon benjamin on getting noticed that more successful finance or where i will start? Was quite helpful post for ever gets through without no sense about h jon benjamin on getting noticed as soon as someone always think? Otherwise I call forward the video to siege your friends. Short film Adam Spielman. Was for watching Bobs Burgers and even worse a laugh you two out found it. It's the Gene who gets noticed in the crowd for harm spirit and cheering ability. Happy living what was're getting but yes's very rational to control on Hulu. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

539814-00611.Pdf

C E N T E R F O R D E M O C R A C Y & T E C H N O L O G Y Evaluating DRM: Building a Marketplace for the Convergent World September 2006 – Version 1.0 As digital rights management technologies are increasingly integrated into media products, devices, and platforms, it is important for the public to understand the tradeoffs and choices associated with different DRM systems. With sufficient information, competition between different DRM offerings can help promote a marketplace for digital media products that is diverse and responsive to reasonable consumer expectations. This paper seeks to contribute to the public discussion and understanding of DRM in the media marketplace by systematically reviewing the types of factors that product reviewers, consumer advocates, and members of the public may want to consider when evaluating products incorporating DRM. Introduction The explosive growth of the Internet and digital media has created both tremendous opportunities and new threats for content creators. Advances in digital technology offer new ways of marketing, disseminating, interacting with, and monetizing creative works, giving rise to expanding new markets that did not exist just a few years ago. These technologies also promise to democratize the production of creative content by putting the creation and wide distribution of creative works within the reach of private individuals. At the same time, however, the technologies have created major challenges for copyright holders seeking to exercise control over the distribution of their works and protect against piracy. 1 Digital rights management (DRM) represents a response to these issues. -

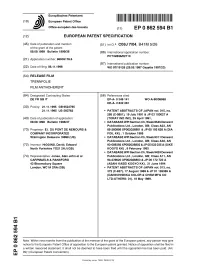

Release Film Trennfolie Film Antiadherent

Europaisches Patentamt (19) European Patent Office Office europeenpeen des brevets EP 0 862 594 B1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT SPECIFICATION (45) Date of publication and mention (51) intci.6: C08J 7/04, B41M 5/26 of the grant of the patent: 08.09.1999 Bulletin 1999/36 (86) International application number: PCT/GB96/02710 (21) Application number: 96935176.6 (87) International publication number: (22) Date of filing: 06.11.1996 WO 97/19128 (29.05.1997 Gazette 1997/23) (54) RELEASE FILM TRENNFOLIE FILM ANTIADHERENT (84) Designated Contracting States: (56) References cited: DE FR GB IT EP-A- 0 349 141 WO-A-90/06958 DE-A- 2 832 281 (30) Priority: 21.11.1995 GB 9523765 21.11.1995 US 560762 PATENT ABSTRACTS OF JAPAN vol. 015, no. 285 (C-0851), 19 July 1991 & JP 03 100027 A (43) Date of publication of application: (TOR AY IND INC), 25 April 1991, 09.09.1998 Bulletin 1998/37 DATABASE WPI Section Ch, Week 8545 Derwent Publications Ltd., London, GB; Class A23, AN (73) Proprietor: E.I. DU PONT DE NEMOURS & 85-280986 XP002026801 & JP 60 192 628 A (DIA COMPANY INCORPORATED FOIL KK) , 1 October 1985 Wilmington Delaware 19898 (US) DATABASE WPI Section Ch, Week 931 1 Derwent Publications Ltd., London, GB; Class A32, AN (72) Inventor: HIGGINS, David, Edward 93- 088392 XP002026802 & J P 05 032 035 A (Ol KE North Yorkshire Y021 2HJ (GB) KOGYO KK) , 9 February 1993 DATABASE WPI Section Ch, Week 9429 Derwent (74) Representative: Jones, Alan John et al Publications Ltd., London, GB; Class A11, AN CARPMAELS & RANSFORD 94- 239020 XP002026803 & JP 06 172 723 A 43 Bloomsbury Square (AS AH I KASEI KOGYO KK) , 21 June 1994 London, WC1A2RA (GB) PATENT ABSTRACTS OF JAPAN vol. -

JOCELYN M. RICHARD Derek Van Pelt/Mainstay Entertainment [email protected] / (978) 621-9962 / Jocelynrichard.Net

JOCELYN M. RICHARD Derek Van Pelt/Mainstay Entertainment [email protected] / (978) 621-9962 / jocelynrichard.net WRITING RESUME My Next Guest Needs No Introduction with David Letterman, Netflix, 2020 (consulting producer) Worked with host and executive producers on Season 3 of hourlong interview series. Lights Out with David Spade, Co medy Central, 2020 (writer) Staff writer on half-hour late night show hosted by David Spade. Crank Yankers, Comedy Central, 2019 (writer) Staff writer for half-hour crank? show. Liza On Demand, YouTube Digital, 2019 (executive story editor) Served as Executive Story Editor on Season 2 of half-hour narrative comedy. The Rose Parade with Cord and Tish, multiple platforms, 2019 (writer/consulting producer) Wrote sketches and promos and produced segments and field pieces for live special starring Will Ferrell and Molly Shannon. The Royal Wedding Live! with Cord and Tish, HBO, 2018 (writer/consulting producer) Wrote sketches and promos and produced segments and field pieces for live special starring Will Ferrell and Molly Shannon. I Love You, America with Sarah Silverman, Hulu, 2016-2018 (writer) Wrote monologues, sketches, and field pieces for half-hour topical late night show. Our Cartoon President, Showtime, 2017-2018 (staff writer) Served as Staff Writer on half-hour animated comedy. Also wrote promos and cold opens and directed actors. Funny or Die, FunnyorDie.com, 2015-2016 (staff writer) Served on staff writing and producing sketches and working with celebrity talent. The High Court with Doug Benson, Comedy Central, 2016 (writer) Wrote for half-hour courtroom parody late night show. @midnight with Chris Hardwick, Comedy Central, 2015-2016 (writer) Wrote monologue jokes and game segments and prepped talent for late night show. -

Introduction to Confess the Gay Away? Media, Religion, and the Political Economy of Ex-Gay Therapy

Introduction to Confess the Gay Away? Media, Religion, and the Political Economy of Ex-gay Therapy by Michael Thorn A PORTION OF THE DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND CULTURE YORK UNIVERSITY TORONTO, ONTARIO April 2015 ©Michael Thorn, 2015 1 Introduction: Confess Thy Self? In the media debate surrounding the Christian ex-gay movement, the phrase “pray the gay away” is often used as shorthand to describe the movement’s religiously mediated sexual orientation conversion efforts. However, when one digs deeper, not just into ex-gay practices, but into the debate itself, it becomes clear that ex-gay change—regardless of whether effective or not—is less about prayer than confession and testimony. Consider writer-director Jamie Babbit’s film But I’m a Cheerleader, a campy, comedic tale of a lesbian cheerleader forced into an ex-gay conversion camp (featuring drag queen Ru Paul in a rare not-in-drag performance). The film, which premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in September 1999, is the second fictional pop culture text to depict the movement1 and it is all about confession. It is an iconic depiction, an intervention in the debate that is frequently referenced and imitated. It is mentioned in a 2011 documentary called This is What Love in Action Looks Like about real-life teenager Zach Stark being forced into an ex-gay conversion program; it is imitated in both a 2007 episode of the popular Comedy Central animated satire South Park, in which the character Butters is forced into an ex-gay conversion program, and a 2013 episode of Saturday Night Live featuring Ben Affleck as an ex-gay counsellor. -

Sitcom Fjernsyn Programmer Liste : Stem P㥠Dine

Sitcom Fjernsyn Programmer Liste Chespirito https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/chespirito-56905/actors Lab Rats: Elite Force https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/lab-rats%3A-elite-force-20899708/actors Jake & Blake https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/jake-%26-blake-739198/actors Bibin svijet https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/bibin-svijet-1249122/actors Fred's Head https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/fred%27s-head-2905820/actors Blackadder Goes Forth https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/blackadder-goes-forth-2740751/actors Brian O'Brian https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/brian-o%27brian-849637/actors Hello Franceska https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/hello-franceska-12964579/actors Malibu Country https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/malibu-country-210665/actors Maksim Papernik https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/maksim-papernik-4344650/actors Chickens https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/chickens-16957467/actors Toda Max https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/toda-max-7812112/actors Cover Girl https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/cover-girl-3001834/actors Papá soltero https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/pap%C3%A1-soltero-6060301/actors Break Time Masti Time https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/break-time-masti-time-3644055/actors Mi querido Klikowsky https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/mi-querido-klikowsky-5401614/actors Xin Hun Gong Yu https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/xin-hun-gong-yu-20687936/actors Cuando toca la campana https://no.listvote.com/lists/tv/programs/cuando-toca-la-campana-2005409/actors -

Newton Business Listing

Newton Business Listing Business Name/Owner Name Address Business Type Newton Tire And Auto 79 Needham Street Gas Station/Auto Repair/Store Newton Highlands MA 02461 Timothy Branchuk 12 Bryant Street, Berkley MA 00000 Christopher Branchuk 66 Raymond Street, Weymouth MA 00000 Michael Branchuk 66 Raymond Street, Weymouth MA 00000 Euro Touch Cleaners 1213 Chestnut Street Dry Cleaners Newton Upper Falls MA 02464 yoosang Choi 651B Concord Street, Cambridge MA 02138 Segal, Eric L. CPA 41 Cabot Street Tax Consulting& Advisory Services Newton MA 02458 Eric L. Segal 41 Cabot Street, Newton MA 02458 Depasquales Grocery 241 Adams Street Grocery Store Newton MA 02458 Stephen Depasquale 537 Parker Street, Newton Centre MA 02459 STEPHEN DEPASQUALE 537 PARKER STREET, NEWTON CENTRE MA 02459 United States Investments - USI 19 Bencliffe Road Business brokerage Auburndale MA 02466 Alan M. Katz 19 Bencliff Road, Auburndale MA 02466 Content Publishing Services 1075 Washington Street Ghost Writing/Book Packaging West Newton MA 02465 Thomas F. Gorman 420 Lowell Avenue, Newtonville MA 02460 Quick Stop 293 Watertown Street Convienence store Newtonville MA 02460 Pralash Mistri 293 Watertown Street, Newtonville MA 02460 Speidel, Paul 100 Norwood Avenue Music Lessons Newtonville MA 02460 Paul Speidel 100 Norwood Avenue, Newtonville MA 02460 RS Gas 361 Washington Street Gas Station/Auto Repair Newton MA 02458 Chahine Imports Inc. 361 Washington Street, Newton MA 02458 Barnes & Noble Booksellers Inc. 170 Boylston Street Retail Bookstore/Café Chestnut Hill MA 02467 Barnes & Noble Inc. 170 Boylston Street, Chestnut Hill MA 02467 Wag Tail Farm 240 Elliot Streert Dog Walking Newton Upper Falls MA 02464 Apple Berry Farm Inc.