The Raven and Allan Parson

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 080, No 150, 7/14/1977." 80, 150 (1977)

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository 1977 The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 7-14-1977 New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 080, No 150, 7/ 14/1977 University of New Mexico Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1977 Recommended Citation University of New Mexico. "New Mexico Daily Lobo, Volume 080, No 150, 7/14/1977." 80, 150 (1977). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/daily_lobo_1977/77 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The aiD ly Lobo 1971 - 1980 at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1977 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ..... - ..• - ... -' -·· '")".~ ~ {; fl ,.;v'l (\ ..... _.--~. ..A -. '• I ~~~ ·' f ¢'1~·. '181. : i I lAN'"'OG.\ ...V l ..... ·E·-~. .-·m~·! .l ~, ..-.~ ~~~~~ :, -- - !,'1 e-g··e· ncy '4.' •, # .. i '<;" • t ... -:·:: ., ., i ' ' .. - ,.. ..)_: '' .. '\ ··~· ~ .'{' ' ·~ ' ., ..., · ·Rldu•d·L· ~lleib«r .". , ·? '~;;a~a<lemic.cQmmunity,'' · ·· · · hospital has had s()me horrendous ,. • ·Four ._.emergency ·-medicih!=.cl9c;;.¢ ·. Th.~. ~llief complaint voiced.by ·financial·problemsin thelast-_ye$1. ,-, ..,, ~ · tors from the emer~en~ roor.rr at !:th~;· phy~icians was· the -~~~k ()f Nobody l,la$ bousht anything· new .t.•"'"" 7 ~; · · BCMC .. have ' submitted their'· eguipment and support from tbe .the the last year, incl\lding the •fl resignations effective July J. T.heir .. ho,Spital. · Marburs said that the · emers~O,fY; r~om.'' . Napolitano_ .is . <•)) · ·res•snatioQs leav~- · only· .. on" . ideal . emergency room situation the. dean··.· p( · the: ·UNM · Medical ','1 ,,' '. emersency m-edicine specialists ·at · · would· igclude· seven. or ,eislii ~hoot . -

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse

Mixed Media December Online Supplement | Long Island Pulse http://www.lipulse.com/blog/article/mixed-media-december-online-supp... currently 43°F and mostly cloudy on Long Island search advertise | subscribe | free issue Mixed Media December Online Supplement Published: Wednesday, December 09, 2009 U.K. Music Travelouge Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out and Gimmie Shelter As a followup to our profile of rock photographer Ethan Russell in the November issue, we will now give a little more information on the just-released Rolling Stones projects we discussed with Russell. First up is the reissue of the Rolling Stones album Get Yer Ya-Ya’s Out!. What many consider the best live rock concert album of all time is now available from Abcko in a four-disc box set. Along with the original album there is a disc of five previously unreleased live performances and a DVD of those performances. There is a also a bonus CD of five live tracks from B.B. King and seven from Ike & Tina Turner, who were the opening acts on the tour. There is also a beautiful hardcover book with an essay by Russell, his photographs, fans’ notes and expanded liner notes, along with a lobby card-sized reproduction of the tour poster. Russell’s new book, Let It Bleed (Springboard), is now finally out and it’s a stunning visual look back on the infamous tour and the watershed Altamont concert. Russell doesn’t just provide his historic photos (which would be sufficient), but, like in his previous Dear Mr. Fantasy book, he serves as an insightful eyewitness of the greatest rock tour in history and rock music’s 60’s live Waterloo. -

Beatles, Pink Floyd Engineer, Alan Parsons Rips Audiophiles

Beatles, Pink Floyd Engineer, Alan Parsons Rips Audiophiles Alan Parsons, producer, musician and sound engineer of Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon, says audiophiles overpay for equipment while ignoring room acoustics. In an exclusive interview with CE Pro, Alan Parsons, renowned sound engineer for Pink Floyd's Dark Side of the Moon and for the Beatles, says hi-fi pros focus too much on equipment and brand names, when they should put more energy into room acoustics. He also says some surround- sound systems “really aren’t that bad.” All this from the audio wizard behind Dark Side of the Moon, and the name sake of the Alan Parson’s Project. Parsons broke into the music industry in the late 1960s when he was hired by Abbey Road Studios to work as an assistant engineer. As an assistant engineer, Parsons’ career started at a point where most music lovers only dream of reaching - working on the last two Beatles’ albums. As a full-fledged engineer, Parsons worked on projects with Paul McCartney and the Hollies, but it was his efforts on the benchmark album Dark Side of the Moon that launched his career. Throughout the rest of the 1970s and 1980s, Parsons released several albums under the name of Alan Parsons Project (APP). The 1990s marked a shift in direction for Parsons that was highlighted by his dropping of “Project” from his band name. As he entered the 2000s, Parsons continued to release new music, which includes his first foray into the electronica genre when he released 2004’s A Valid Path. -

Program Book Final 1-16-15.Pdf

4 5 7 BUFFALO PHILHARMONIC ORCHESTRA TABLE OF CONTENTS | JANUARY 24 – FEBRUARY 15, 2015 BPO Board of Trustees/BPO Foundation Board of Directors 11 BPO Musician Roster 15 Happy Birthday Mozart! 17 M&T Bank Classics Series January 24 & 25 Alan Parsons Live Project 25 BPO Rocks January 30 Ben Vereen 27 BPO Pops January 31 Russian Diversion 29 M&T Bank Classics Series February 7 & 8 Steve Lippia and Sinatra 35 BPO Pops February 13 & 14 A Very Beary Valentine 39 BPO Kids February 15 Corporate Sponsorships 41 Spotlight on Sponsor 42 Meet a Musician 44 Annual Fund 47 Patron Information 57 CONTACT VoIP phone service powered by BPO Administrative Offices (716) 885-0331 Development Office (716) 885-0331 Ext. 420 BPO Administrative Fax Line (716) 885-9372 Subscription Sales Office (716) 885-9371 Box Office (716) 885-5000 Group Sales Office (716) 885-5001 Box Office Fax Line (716) 885-5064 Kleinhans Music Hall (716) 883-3560 Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra | 499 Franklin Street, Buffalo, NY 14202 www.bpo.org | [email protected] Kleinhan's Music Hall | 3 Symphony Circle, Buffalo, NY 14201 www.kleinhansbuffalo.org 9 MESSAGE FROM BOARD CHAIR Dear Patrons, Last month witnessed an especially proud moment for the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra: the release of its “Built For Buffalo” CD. For several years, we’ve presented pieces commissioned by the best modern composers for our talented musicians, continuing the BPO’s tradition of contributing to classical music’s future. In 1946, the BPO made the premiere recording of the Shostakovich Leningrad Symphony. Music director Lukas Foss was also a renowned composer who regularly programmed world premieres of the works of himself and his contemporaries. -

ALAN PARSONS Eye 2 Eye - Live in Madrid (Rock)

ALAN PARSONS Eye 2 eye - live in madrid (Rock) Année de sortie : 2010 Nombre de pistes : 13 Durée : 68' Support : MP3 Provenance : Reçu du label Formé en 1975 par Alan PARSONS et Eric WOOLFSON, et vite rejoints par de nombreux autres musiciens de renom, les anglais d'ALAN PARSONS PROJECT ont jusqu'en 1990 (et encore maintenant !) "inondé" à satiété les ondes radiophoniques du monde entier avec leurs hits que sont les Eye In The Sky et son prologue Sirius, Don't Answer Me, Psychobabble, I Wouldn't Want To Be like You et autres Games People Play. Après une dizaine d'albums, quelques live plus ou moins "pirates", des compilations best of, l'aventure prend fin et Alan PARSONS continue seul sa carrière sous son nom (je me permets ici de vous renvoyer vers, par exemple, le site internet de BIG BANG et son dossier sur le groupe pour une bibliographie discographique riche et fouillée !). Enregistré en mai 2004 à Madrid en Espagne, Alan PARSONS (claviers, guitare acoustique et chant), ici accompagné de P.J OLSSON (guitare acoustique et chant), G. TOWNSEND (guitares et chant), S. MURPHY (batterie), J. MONTAGNA (basse) et M. FOCARAZZO (claviers), nous offrent un superbe live ou quasiment tous les hits cités ci-dessus du ALAN PARSONS PROJECT s'y trouvent enchaînés. Alan revisite une partie des albums du groupe, de I Robot (1977) à Ammonia Avenue (1984). Et pour les fans quarantenaires qui ont "marché" au son de ses hymnes dans leur jeunesse, ces 13 titres respirent le bonheur et plaquent des retours en arrière chargés d'émotions et de souvenirs pittoresques ! Souvent étiquetée Rock Progressif puis Pop Rock, la musique du groupe est à rapprocher des PINK FLOYD par exemple. -

MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE Official News Guide from Yamaha & Easy Sounds for Yamaha Music Production Instruments

MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE OFFICIAL NEWS GUIDE FROM YAMAHA & EASY SOUNDS FOR YAMAHA MUSIC PRODUCTION INSTRUMENTS 04|2014 SPECIAL EDITION Contents 40th Anniversary Yamaha Synthesizers 3 40 years Yamaha Synthesizers The history 4 40 years Yamaha Synthesizers Timeline 5 40th Anniversary Special Edition MOTIF XF White 23 40th Anniversary Box MOTIF XF 28 40th Anniversary discount coupons 30 40th Anniversary MX promotion plan 31 40TH 40th Anniversary app sales plan 32 ANNIVERSARY Sounds & Goodies 36 YAMAHA Imprint 41 SYNTHESIZERS 40 YEARS OF INSPIRATION YAMAHA CELEBRATES 40 YEARS IN SYNTHESIZER-DESIGN WITH BRANDNEW MOTIF XF IN A STUNNIG WHITE FINISH SARY PRE ER M V IU I M N N B A O X H T 0 4 G N I D U L C N I • FL1024M FLASH MEMORY Since 1974 Yamaha has set new benchmarks in the design of excellent synthesizers and has developed • USB FLASH MEMORY (4GB) innovative tools of creativity. The unique sounds of the legendary SY1, VL1 and DX7 have influenced a INCL. SOUND LIBRARIES: whole variety of musical styles. Yamaha‘s know-how, inspiring technique and the distinctive sounds of a - CHICK’S MARK V - CS-80 40-years-experience are featured in the new MOTIF XF series that is now available in a very stylish - ULTIMATE PIANO COLLECTION white finish. - VINTAGE SYNTHESIZER COLLECTION YAMAHASYNTHSEU YAMAHA.SYNTHESIZERS.EU YAMAHASYNTHESIZEREU EUROPE.YAMAHA.COM MUSIC PRODUCTION GUIDE 04|2014 40TH ANNIVERSARY YAMAHA SYNTHESIZERS In 1974 Yamaha produced its first portable Yamaha synthesizers and workstations were and still are analog synthesizer with the SY-1. The the first choice for professionals and amateurs in the multi- faceted music business. -

The Alan Parsons Project Pyramid Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Alan Parsons Project Pyramid mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pyramid Country: Benelux Released: 1979 Style: Art Rock, Prog Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1713 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1359 mb WMA version RAR size: 1382 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 187 Other Formats: ADX MP1 MP3 APE AIFF AU RA Tracklist A1 Voyager 2:24 A2 What Goes Up... 3:31 A3 The Eagle Will Rise Again 4:20 A4 One More River 4:15 A5 Can't Take It With You 5:06 B1 In The Lap Of Gods 5:27 B2 Pyramania 2:45 B3 Hyper-Gamma-Spaces 4:19 B4 Shadow Of A Lonely Man 5:34 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Arista Records, Inc. Copyright (c) – Arista Records, Inc. Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Mixed At – Abbey Road Studios Published By – Woolfsongs Ltd. Published By – Careers Music, Inc. Published By – Irving Music, Inc. Pressed By – Columbia Records Pressing Plant, Santa Maria Credits Acoustic Guitar [Acoustic Guitars] – Alan Parsons, David Paton, Ian Bairnson Arranged By [Orchestra And Choir], Conductor [Orchestra And Choir Conducted By] – Andrew Powell Bass – David Paton Chorus Master [Choirmaster] – Bob Howes* Composed By [All Songs] – Alan Parsons, Eric Woolfson Cover, Design – Hipgnosis Drums, Percussion – Stuart Elliot* Electric Guitar [Electric Guitars] – Ian Bairnson Engineer [Assistant Engineers] – Chris Blair, Pat Stapley Engineer [Engineered By] – Alan Parsons Executive-Producer – Eric Woolfson Keyboards – Duncan Mackay, Eric Woolfson Mastered By [Mastering By] – Chris Blair Photography By [Photos] – Hipgnosis , Brimson* Producer [Produced By] – Alan Parsons Vocals – Colin Blunstone, David Paton, Dean Ford, Jack Harris, John Miles, Lenny Zakatek Written-By [All Tracks] – Alan Parsons, Eric Woolfson Notes 12" X 24" insert contains lyrics, credits, and artwork with a poster on the reverse side of the full cover artwork Light blue inner sleeve with no printing. -

“The Dark Side of the Moon”—Pink Floyd (1973) Added to the National Registry: 2012 Essay By: Daniel Levitin (Guest Post)*

“The Dark Side of the Moon”—Pink Floyd (1973) Added to the National Registry: 2012 Essay by: Daniel Levitin (guest post)* Dark Side of the Moon Angst. Greed. Alienation. Questioning one's own sanity. Weird time signatures. Experimental sounds. In 1973, Pink Floyd was a somewhat known progressive rock band, but it was this, their ninth album, that catapulted them into world class rock-star status. “The Dark Side of the Moon” spent an astonishing 14 years on the “Billboard” album charts, and sold an estimated 45 million copies. It is a work of outstanding artistry, skill, and craftsmanship that is popular in its reach and experimental in its grasp. An engineering masterpiece, the album received a Grammy nomination for best engineered non-classical recording, based on beautifully captured instrumental tones and a warm, lush soundscape. Engineer Alan Parsons and Mixing Supervisor Chris Thomas, who had worked extensively with The Beatles (the LP was mastered by engineer Wally Traugott), introduced a level of sonic beauty and clarity to the album that propelled the music off of any sound system to become an all- encompassing, immersive experience. In his 1973 review, Lloyd Grossman wrote in “Rolling Stone” magazine that Pink Floyd’s members comprised “preeminent techno-rockers: four musicians with a command of electronic instruments who wield an arsenal of sound effects with authority and finesse.” The used their command to create a work that introduced several generations of listeners to art-rock and to elements of 1950s cool jazz. Some reharmonization of chords (as on “Breathe”) was inspired by Miles Davis, explained keyboardist Rick Wright. -

NAACP Head Speaks Here

-< SEPTEMBER 20' 1979 ISSUE 349 ........................................................................... ·.T~... -_· UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI/SAINT LOUIS NAACP head speaks here IJDda Tate the nation' as well. son, who lie called " the greatest "There is no question in my Civil Rights president in the Benjamin Hooks, executive mind and ' from the perspective whole history of this nation." director of the National Asso of those of us who feel that this He brought up the fact that ' ciation for the Advancement of country has never fully lived up while much legislatioh concer Colored People (NAACP), spoke to its promises," Hooks said, ning civil rights was passed to about 250 UMSL students "that the last three or four during the 60's, blacks are still Tuesday. years-in fact, the last 10 struggling to attain the full Considering that the lecture years-have seen us drift back potential of this legislation. ' was held at 11am, tfle turnout into the conservative mode. Hooks went on to describe was good. Most of the seats in " It was a beautiful time for' life for blacks before the Civil J.C. Pen~ey Auditorium were Rights movement. filled as students and faculty all of the minority ,people of this nation during the late 50's .. ' .. gathered to hear one of the Born in Memphis, Tennes 'foremost black leaders in Ame-, Many (black) groups (and see, Hooks served as a soldier in leaders) produced a sort of new rica today. World War II and consequently feeling in the black community Hooks spoke for about 40 ' became a decorated combat minutes and answered questions of non-acceptance of traditional veteran: Despite his service to ways of life." from the au,dlence for another the country, he encountered problems in attaining a higher 20. -

Polytram Changes Budget Import Mart Booms Scorpions Cover by FRED GOODMAN Ment of Odds and Ends from Around That His Firm Does Have American the World

SM 14011 MMNIFIN BBO 9GREENLYMONT00 MARP6 NEWSPAPER MONTY GREENLY C3 10 37410 ELM UC Y LONG PEACH CA 90807 A B°Ilboard Publication The Internatior Newsweekly Of Music & Home Entertainment May 5, 1984 $3 (U.S.) AFTER RACK COMPLAINT DESPITE LABELS' EFFORTS Polytram Changes Budget Import Mart Booms Scorpions Cover By FRED GOODMAN ment of odds and ends from around that his firm does have American the world. customers, but that it counsels NEW YORK complaint from That attitude is apparently not -A NEW YORK -The U.S. market caution. a key rack account has led Mercury/ shared by Handleman or some of its "It's a large market," says one for imported budget, cutout and "We want to keep the U.S. compa- PolyGram to market two different customers. Mario DeFilippo, vice wholesaler who carries both domestic overstock albums is thriving. Despite nies happy," he says. "The customer covers of the Scorpions' top 10 album president of purchasing for the rack- and imported budget titles. "It basi- the efforts of the Recording Industry doesn't want to go out on a limb. But "Love At First Sting." . jobber, says that objections to album cally exists because the American Assn. of America, CBS Records and there is a whole midprice range we According to the label, Wal -Mart, cover art as well as lyrics are "a com- market is loaded with crap and the other American manufacturers to sti- supply that is not available in Ameri- a 670 -store discount chain racked by mon complaint from our customers." dual stuff is cheaper. -

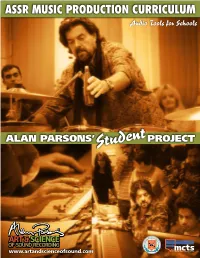

Student Project

ASSR MUSIC PRODUCTION CURRICULUM Audio Tools for Schools ALAN Parsons’ Student project www.artandscienceofsound.com A LETTER FROM THE FOUNDERS usic is a precious resource. Being able Mto capture or record music for future generations to enjoy is one of music’s most valuable skills. Today Music Production is something anyone can do, armed with a cellphone and a decent internet connection. Sure you’ll soon want a microphone; and then another mic, and then another mic. Speakers help of course, and pro software gives you the sort of power that only major recording studios like Capitol and Abbey Road had back in the day. Speaking of which, back in the day when we were trying to carve out our careers, there weren’t any alternatives to a recording studio. And there weren’t any schools you could go to to learn about recording. Alan got a job as an assistant engineer at Abbey Road and Julian signed with Charisma Records as a writer and keyboard player. We listened, observed, tried, occasionally failed, Since 2010 we’ve dedicated ourselves to lifting the lid on what but eventually started to make sense of this magical thing we call it takes to record music; unravelling some of the mysteries ‘making records.’ behind and in front of the glass. Learning Music Production Today, even though physical records might seem to have gone and Audio Engineering isn’t rocket science (though Alan does the way of the Dodo, there’s still a thrill in creating music… have strong connections with NASA these days) and it’s not art creating something that didn’t exist fifteen minutes ago. -

The Alan Parsons Project Tales of Mystery and Imagination Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Alan Parsons Project Tales Of Mystery And Imagination mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Rock Album: Tales Of Mystery And Imagination Country: Portugal Released: 1976 Style: Art Rock, Experimental MP3 version RAR size: 1983 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1761 mb WMA version RAR size: 1442 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 466 Other Formats: WMA MPC MP3 VOX MP2 MP1 AAC Tracklist A1 A Dream Within A Dream 3:40 A2 The Raven 4:00 A3 The Tell-Tale Heart 4:37 A4 The Cask Of Amontillado 4:27 A5 (The System Of) Doctor Tarr And Professor Fether 4:14 The Fall Of The House Of Usher (15:02) B1.I Prelude B1.II Arrival B1.III Intermezzo B1.IV Pavane B1.V Fall B2 To One In Paradise 4:29 Companies, etc. Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Mixed At – Abbey Road Studios Published By – Woolfsongs Ltd. Published By – Fox Fanfare Music, Inc. Distributed By – Procope, SARL Phonographic Copyright (p) – 20th Century Records Copyright (c) – Woolfsongs Ltd. Distributed By – Movieplay Portuguesa Record Company – 20th Century Records Mastered At – The Mastering Lab Credits Arranged By [Orchestra & Choir], Conductor [Orchestra & Choir] – Andrew Powell Bass – David Paton, Joe Puerta Cimbalom, Kantele – John Leach Contractor [Orchestral] – David Katz Cover, Sleeve [Frontsleeve Designed By], Design [Frontsleeve Designed By] – Hipgnosis Double Bass [Sting Bass] – Darryl Runswick* Drums – Burleigh Drummond, Stuart Tosh Engineer – Alan Parsons Engineer [Assistant] – Chris Blair, Pat Stapley Executive-Producer – Eric Woolfson Guitar – Alan Parsons, David Pack, David Paton, Ian Bairnson Keyboards – Alan Parsons, Andrew Powell, Billy Lyall, Christopher North, Eric Woolfson, Francis Monkman Layout [Inside], Artwork [Graphics] – Colin Elgie Mastered By – Doug Sax Photography By – Aubrey Powell, Peter Christopherson, Storm Thorgerson Photography By [Alan Parsons] – Sam Emerson Producer – Alan Parsons Sleeve [Frontsleeve Designed By], Design [Frontsleeve Designed By] – Hardie* Technician [Technical Consultant] – Gordon Parry, Keith O.