GLOBAL CITIZENSHIP KEYNOTE ADDRESS Ban Ki-Moon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 124, 2004-2005

2004-2005 SEASON BOSTON SYM PHONY *J ORCHESTRA JAM ES LEVI N E ''"- ;* - JAMES LEVINE MUSIC DIRECTOR BERNARD HAITINK CONDUCTOR EMERITUS SEIJI OZAWA MUSIC DIRECTOR LAUREATE Invite the entire string section for cocktails. With floor plans from 2,300 to over Phase One of this 5,000 square feet, you can entertain magnificent property is in grand style at Longyear. 100% sold and occupied. Enjoy 24-hour concierge service, Phase Two is now under con- single-floor condominium living struction and being offered by at its absolute finest, all Sotheby's International Realty & harmoniously located on Hammond Residential Real Estate an extraordinary eight- GMAC. Priced from $1,725,000. acre gated community atop prestigious Call Hammond at (617) 731-4644, Fisher Hill ext. 410. LONGYEAR. a/ l7isner jtfiff BROOKLINE V+* rm SOTHEBY'S Hammond CORTLAND IIIIIIUU] SHE- | h PROPERTIES INC ESTATE 3Bhd International Realty REASON #11 open heart surgery that's a lot less open There are lots of reasons to consider Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like minimally invasive heart surgery that minimizes pain, reduces cosmetic trauma and speeds recovery time. From cardiac services and gastroenterology to organ transplantation and cancer care, you'll find some of the most cutting-edge medical advances available anywhere. To find out more, visit www.bidmc.harvard.edu or call 800-667-5356. Beth Israel A teaching hospital of Deaconess Harvard Medical School Medical Center Red | the Boston Affiliated with Joslin Clinic | A Research Partner of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Official Hospital of James Levine, Music Director Bernard Haitink, Conductor Emeritus Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Laureate 124th Season, 2004-2005 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

2018 Annual Meeting

2018 ANNUAL MEETING If we live in the Spirit, let us also walk in the Spirit. —Galatians 5:25 JUNE 2–4 Program and guide WELCOME Welcome to Annual Meeting! This Manual-based activity is more than a yearly embrace of one another in the work of Church, however joyful and inspiring these shared moments are. As with the earliest disciples when they gathered together after our Master’s ascension, we, too, continually find there is more to discover, more to engage with, and more that burns within our hearts of the living Word. It impels us to walk in the Spirit each day, finding in every activity and every encounter an opportunity to witness to God’s goodness and grace. It’s not always easy. The resistance the first Christians faced from entrenched material systems of thought and power could have been discouraging, even overwhelming. But the joy of knowing God’s true nature as All—as eternal Life and infinite Love— sustained them. And following Christ Jesus brought them step by step into a new sense of reality and its present possibilities. Whether taking those footsteps in the first century or in the 21st, it brings disciples of any age the same satisfying sense of fellowship and purpose in this holiest Cause. When we gather like this, we feel the power of Spirit animating us as one global movement. As we support one another and respond to the world around us, we recognize how essential and needed each of us is. With renewed affection and expectation, let us walk forward in the Spirit together. -

Newsletter Spring 2012 Contents

Newsletter Spring 2012 CoNteNtS contents4 3 Library NewS You’re invited! Library Open House New Exhibit Opens New Trustee on The Mary Baker Eddy Library Board Behind the Scenes: Curators in Action 7 CurreNt ProgramS First Saturday Events: Spring 2012 10 8 PaSt ProgramS April School Vacation Week Program Believing Young Voices Caring for Christmas & Charity Drive First Night 2012 Paths of Peace in Crisis February School Vacation Week Program 11 Author Talk: Keith Collins 13 ColleCtions From the Archives: Spotlight on Walter Watson From the Collection: Object of the Month 16 Noteworthy 15 17 DiD you kNow? 18 what’S New 19 ABOUT On the cover: Printing plates from the first edition of Science and Health. This image is from the new exhibit, Impressions on Paper: Mary Baker Eddy, Writer Library NewS A sampling of items displayed during last year’s event. You’re invited! Library Open House Join us on Sunday, June 3, from 11:30 a.m. to 1:45 p.m., to help kick off our 10 year anniversary celebration with a Library Open House. Staff from all depart- ments will be stationed throughout the building to introduce you to their work and share more about the Library’s collections, and through them, the history of Mary Baker Eddy and the Christian Science movement. On the third floor, don’t miss a special opportunity to hear the Curatorial staff highlight key treasures from our collections. Visitors will be encouraged to ask questions about these rarely-seen objects. On the fourth floor, Research & Reference Services will have items related to the “Busy Bees” on view as well as fascinating historical documents to read and ponder. -

Boston Avenue of Arts Walking

Boston: America’s Walking City walk/with stops: 1.25 hours Explore Boston on foot! Walking is an easy, pleasant walk/no stops: 45 minutes Greater Boston Convention & Visitors Bureau Visitor Center and stress-free way to enjoy your visit. It is one of distance: 15 blocks/1.5 miles Open 9–5 daily the best forms of exercise to keep you fit. Known for historic and picturesque neighborhoods, Boston has outstanding pedestrian features including: • A compact and relatively flat layout with European u style streets that are safe, lively and diverse. a e • Centrally located points of interest: history, r 5 u entertainment, nightlife, architecture, culture, 0 / 3 B science and arts abound. n o t s s • A great feeling of openness against a backdrop o r B k l o of skyscrapers, thanks to inviting green spaces like a t W i the Boston Common, Commonwealth Avenue Mall © s and the Charles River Esplanade. i • A convenient and affordable subway and bus system V that takes you within steps of your destination. & Everything is within walking distance. And everyone n o in Boston walks. So walk—you’ll feel better for it! i t n s e t r Walks for visitors v n A n This self-guided walk includes points of interest, o e C major conference hotels and the convention site. You h t o might combine the walk with dining. Nearby Boylston n f and Newbury Streets are lined with restaurants and o t o t shops. A stroll in the other direction brings you to the s e o s charming South End. -

MIT Women's League Exercise and Aging: Outrunning Father Time First

MIT Women’s League April/May 2008 newsletter < Weight training and aerobic conditioning to enhance mobility and well-being will be a few of the topics discussed at the Catherine N. Stratton Aging Successfully lecture on April 23. < Designed in the Exercise and Aging: 1960’s by architect I.M. Pei, the Outrunning Father Christian Science Plaza in Boston Time includes a reflecting pool, a colonnade, and a three-story April 23 • 4-6 pm stained glass Mapparium that Wong Auditorium in MIT’s Jack C. Tang visitors can view Center will be the venue for the 21st from the inside. Annual Catherine N. Stratton Aging Successfully Lecture on April 23rd from 4:00-6:00 pm. A collaborative project of First Church of Christ the MIT Medical Department and the MIT Women’s League, this year’s lecture will and Mapparium Tour focus on the effectiveness of exercise as we age with particular emphasis on the April 16 • 12:30 pm The MIT Women’s benefits of strength training. League, founded Our tour will allow us to experience the inside of the First Church of Christ, Scientist in 1913, strives to Popular media, alumni magazines and our health providers urge us to exercise (The Mother Church) built in Boston in connect women in regularly, to do “aerobic conditioning” 1894 in the American Romanesque style. the MIT community with some vigor so that this recurrent The large domed Extension completed in through activities, exercise benefits our cardiovascular 1906 combines Renaissance and Byzantine architectural concepts and houses one of interest groups, and systems, enhancing mobility and general well-being. -

Newsletter Vol

2011 Newsletter Vol. 5, No. 4 Library News Inquirers call us, write us, email us—or walk in and visit us! Research & Reference Services We will continue to welcome patrons, answer On August 1, 2011, Research & Reference Services queries, and host First Saturday educational opened on the fourth floor of the Library. Combining programs highlighting the resources of our the resources of Lending and Reference Services and collections. We have also renovated the collections the Research Room, this new department provides area of our website, making both our on site and access to original materials that document the life of online resources more accessible. Remote users Mary Baker Eddy and the church that she founded should look for the new “Online Resources” page and to the collections of publications previously to gain access to articles and periodicals available housed on the second floor of the Library. Historical through a variety of databases, provided free materials include letters, manuscripts, organizational of charge. They may also search our circulating records, photographs, artifacts, books, periodicals, collections online, explore our archival holdings and audiovisuals. with online Finding Aids, read Object of the Month The Mary Baker Eddy Library collections are an articles, and study frequently answered questions unmatched resource for information about Mary on Ask a Researcher before submitting their own Baker Eddy and the Christian Science movement. queries. Every month, staff respond to hundreds of queries Research & Reference Services is open from about historical correspondence, documents, and 10 a.m. to 4 p.m., Tuesday through Friday and manuscripts by, and about, Mary Baker Eddy and on the first Saturday of every month. -

Item 2 Attachment :History and Social Science Proposed Revised Framework for Public Comment

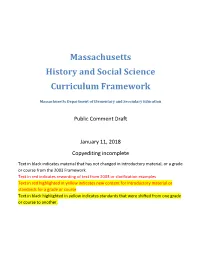

Massachusetts History and Social Science Curriculum Framework Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Public Comment Draft January 11, 2018 Copyediting incomplete Text in black indicates material that has not changed in introductory material, or a grade or course from the 2003 Framework. Text in red indicates rewording of text from 2003 or clarification examples Text in red highlighted in yellow indicates new content for introductory material or standards for a grade or course Text in black highlighted in yellow indicates standards that were shifted from one grade or course to another. This document was prepared by the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education Board of Elementary and Secondary Education Members Mr. Paul Sagan, Chair, Cambridge Mr. Michael Moriarty, Holyoke Mr. James Morton, Vice Chair, Boston Mr. James Peyser, Secretary of Education, Milton Ms. Katherine Craven, Brookline Ms. Mary Ann Stewart, Lexington Dr. Edward Doherty, Hyde Park Dr. Martin West, Newton Ms. Amanda Fernandez, Belmont Ms. Hannah Trimarchi, Chair, Student Advisory Ms. Margaret McKenna, Boston Council, Marblehead Jeff Wulfson, Acting Commissioner and Secretary to the Board The Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education, an affirmative action employer, is committed to ensuring that all of its programs and facilities are accessible to all members of the public. We do not discriminate on the basis of age, color, disability, national origin, race, religion, sex, or sexual orientation. Inquiries regarding the Department’s compliance with Title IX and other civil rights laws may be directed to the Human Resources Director, 75 Pleasant St., Malden, MA, 02148, 781-338-6105. © 2018 Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. -

Foreign Airmail

NIEMAN REPORTS Nieman Reports THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION FOR JOURNALISM AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOL. 64 NO. 3 FALL 2010 VOL. 64 NO. 3 FALL 2010 REPORTING FROM FARAWAY PLACES THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION HARVARDAT UNIVERSITY Reporting From Faraway Places Who Does It and How? ‘to promote and elevate the standards of journalism’ Agnes Wahl Nieman the benefactor of the Nieman Foundation Vol. 64 No. 3 Fall 2010 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University Bob Giles | Publisher Melissa Ludtke | Editor Jan Gardner | Assistant Editor Jonathan Seitz | Editorial Assistant Diane Novetsky | Design Editor Nieman Reports (USPS #430-650) is published Editorial in March, June, September and December Telephone: 617-496-6308 by the Nieman Foundation at Harvard University, E-Mail Address: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098. [email protected] Subscriptions/Business Internet Address: Telephone: 617-496-6299 www.niemanreports.org E-Mail Address: [email protected] Copyright 2010 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Subscription $25 a year, $40 for two years; add $10 per year for foreign airmail. Single copies $7.50. Periodicals postage paid at Boston, Back copies are available from the Nieman office. Massachusetts and additional entries. Please address all subscription correspondence to POSTMASTER: One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138-2098 Send address changes to and change of address information to Nieman Reports P.O. Box 4951, Manchester, NH 03108. P.O. Box 4951 ISSN Number 0028-9817 Manchester, NH 03108 Nieman -

The Mary Baker Eddy Library Elizabeth Helen Webb

Fall04.CVR.agsi.r1 9.8.04 1:48 PM Page OBC11 ExecutiveExecutive EditoEditor MembershipMembership CoCover,ver, AboAbove:ve: A renewalrenewal noticenotice requestingrequesting MaryMary John Trumbull Robert M. and Patricia P. Wilson StephenStephen I.I. DanzanskyDanzansky ForFor informationnformation aboutabout BakerBaker EddyEddy’s suffragesuffrage dues,dues, fromfrom thethe MassachusettsMassachusetts Phyllis Mae and Walter F. Mr. and Mrs. Mel Witt joiningjoining thethe FriendsFriends ofof thethe EditorEditor WoWomanan SuffrageSuffrage Association,ssociation, Marcharch 15,15, 1888.1888. Tule Denise A. Windle MaryMary Ellenllen BurBurd LibrarLibrary andand receivingreceiving thisthis No. Constance Dee Turner Jane Kent Winner (Photo(Photo byby MarkMark Thayer)Thayer) Bonnie L. Turrentine Susan Moore Wintringer BusinessBusiness ManagerManager magazine,magazine, pleaseplease callcall Lyle Frederick Tuttle Carol and Loftin Witcher Virginiairginia HugheHughes 888888.222222.37113711 (for(for callscalls CoCover,ver, BeloBelow:w: Womanoman suffragesuffrage headquartersheadquarters withinwithin thehe UnitedUnited States)tates) Herrn Nils Tuxen Dorothy Lee Booth Witwer DDesignesign Cynthia Ann Tyler The Roland Wolfe Family onon UpperUpper EuclidEuclid Avenue,venue, Cleveland,leveland, Ohio.hio. AtAt F ALL 2004 DeFrancisDeFrancis CarbonCarbone oror 61617.450450.70007000 (for(for Janet J. and Norman Tyler Tara Nicole Wolfe internationalinternational calls).calls). extremeextreme rightright isis MissMiss BelleBelle Sherwin,Sherwin, president,president, -

Newsletter Vol

2010 Newsletter Vol. 4, No. 3 Programs Enriching children’s lives with “One World” This summer, The Mary Baker Eddy Library was proud to once again host “One World,” the free enrichment program for children ages 4–10. The program ran for six consecutive Tuesdays from 10 a.m. to noon, beginning on July 6, and ending August 10. In attendance were local families and nonprofit organizations such as Boston’s Salvation Army, the YMCA of Roxbury, the Boys and Girls Club of Charlestown, and Jamaica Plain’s Kids Arts. Our 2010 attendance target for “One World” was to provide summer cultural enrichment A family enjoys the new exhibit “Life of Service.” for 1,100 children. We are pleased to report that we welcomed over 1,200 attendees. collections. Additional activities took place throughout The purpose of this program is to introduce arts and the Library, including a scavenger hunt, a geography- culture to Boston area youths, as well as emphasize based quiz activity, free admission to the world-famous the importance of literacy. Our participants enjoyed Mapparium®, and a sing-a-long station. assorted craft projects ranging from creating a “stained- glass” globe to decorating their own bookmark; both The Mary Baker Eddy Library strives to provide connect to Mary Baker Eddy and the Library’s historic performances that are both interactive and educational. continued on p. 2 Boston Red Sox mascot, Wally the Green Monster, helped out at reception. Amal Shumar (right) taught kids how to hip-hop dance. 1 Mission Statement Programs “The Mary Baker Eddy Library provides public access and context to original materials Annual Meeting Author Talks and educational experiences about Mary Baker Eddy’s life, ideas, and achievements, The Library hosted three author talks in including her Church. -

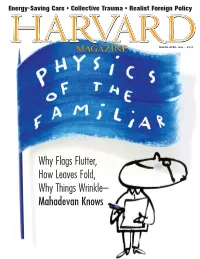

Why Flags Flutter, How Leaves Fold, Why Things Wrinkle– Mahadevan Knows Certifi Ed Pre-Owned Three Years Old BMW and Still Better Than Most Things New

Energy-Saving Cars • Collective Trauma • Realist Foreign Policy MARCH-APRIL 2008 • $4.95 Why Flags Flutter, How Leaves Fold, Why Things Wrinkle– Mahadevan Knows Certifi ed Pre-Owned Three years old BMW and still better than most things new. bmwusa.com/cpo The Ultimate 1-800-334-4BMW Driving Machine® After rigorous inspections only the most pristine vehicles are chosen. That’s why we offer a warranty for up to 6 years or 100,000 miles.* In fact, a Certifi ed Pre-Owned BMW looks so good and performs so well it’s hard to believe it’s pre-owned. But it is, we swear. bmwusa.com/cpo Certifi ed by BMW Trained Technicians / BMW Warranty / BMW Leasing and Financing / BMW Roadside Assistance† Pre-Owned. We Swear. *Protection Plan provides coverage for two years or 50,000 miles (whichever comes ¿ rst) from the date of the expiration of the 4-year/50,000-mile BMW New Vehicle Limited Warranty. †Roadside Assistance provides coverage for two years (unlimited miles) from the date of the expiration of the 4-year/unlimited-miles New Vehicle Roadside Assistance Plan. See participating BMW center for details and vehicle availability. For more information, call 1-800-334-4BMW or visit bmwusa.com. ©2008 BMW of North America, LLC. The BMW name and logo are registered trademarks. 130764_1_v1 1 1/17/08 7:11:31 PM MARCH-APRIL 2008 VOLUME 110, NUMBER 4 FEATURES 30 Saving Money, Oil, and the Climate How to wean ourselves from imported petroleum by powering our vehicles with environmentally benign electricity by Michael B. -

Christian Science Plaza Revitalization Project

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE PLAZA REVITALIZATION PROJECT Overall Site: • Total Site: approximately 14.5 acres • Open Space: about 10.4 acres Parking Garage: • Location: under the Reflecting Pool • Parking: 550 cars • Size: 1,000 feet long x 190 feet wide Reflecting Pool: • Size: 686 feet (nearly 2 football fields) long x 98 feet wide • Average Depth: 28 inches • Water Capacity: approximately 1 million gallons at any one time; and about 3 million gallons/ year due to evaporation and backwashing Children’s Fountain: • Size: 80 foot diameter • Water spray: as high as 40 feet into the air Photos and site plan used by permission of The First Church of Christ, Scientist, and The Mary Baker Eddy Library 2/25/09 Christian Science Publishing House • Completed: 1934 • Architect: Chester Lindsay Churchill • Style: elements of Grecian, Roman and Renaissance architecture • Height: 154 feet / 10 story building • Gross Square Footage: 308,000 • Administrative headquarters for the Church and Publishing Society The Mary Baker Eddy Library • Opened: 2002 • Located in the west wing of the Publishing House building • Library Architect: Ann Beha Architects • Contains: exhibit space, historic collections, research library • The Mapparium® - completed in 1935 – located within the Library Horticultural Hall • Completed: 1901 • Architect: Wilright and Haven • Style: Neo-Georgian • Gross Square Footage: 65,700 square feet / 3 floors with mezzanine • Contains: office space • Leased to 3rd parties Sunday School Building • Completed: 1971 • Architect: I. M. Pei & Partners and Araldo Cossutta, Associated Architects • Height: 59 feet/ 3 story building • Gross Square Footage: 39,000 • Contains: foyer and meeting rooms on ground floor; auditorium on 2nd floor; balcony on 3rd floor 177 Huntington Ave.