R&D Intensity Targets in the Finnish Innovation Policy Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technocratic Governments: Power, Expertise and Crisis Politics in European Democracies

The London School of Economics and Political Science Technocratic Governments: Power, Expertise and Crisis Politics in European Democracies Giulia Pastorella A thesis submitted to the European Institute of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy London, February 2016 1 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 86852 words, excluding bibliography, appendix and annexes. Statement of joint work Chapter 3 is based on a paper co-authored with Christopher Wratil. I contributed 50% of this work. 2 Acknowledgements This doctoral thesis would have not been possible without the expert guidance of my two supervisors, Professor Sara Hobolt and Doctor Jonathan White. Each in their own way, they have been essential to the making of the thesis and my growth as an academic and as an individual. I would also like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council for their generous financial support of my doctoral studies through their scholarship. -

Canadian Committee for the History of the Second World War: First

Canadian Committee for the History of the Second World War ⁄ Comité Canadien de l' Histoire de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale The first conference ⁄ La première conférence at ⁄ au Collège Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean 20 - 22 Oct 1977 Proceedings Compte rendu CANADIAN COMMITTEE FOR THE HISTORY OF THE SECOND WORLD WAR Proceedings of the First Conference Held at Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean Saint-Jean, Quebec 20-22 October, 1977 These proceedings are being distributed with the permission of the authors of the various papers given at our first conference. because of the disparate nature of the subjects it was considered preferable not to seek a publisher for the proceedings, but rather to limit distribution to members of the Canadian Committee and certain other interested people, such as the president and secretary of the international committee. Consequently no attempt has been made to link the papers to an overall theme, and there has not been the rigorous editing that would have accompanied publication. It was a suggestion to hold a conference on the Dieppe landings in 1942 that prompted these meetings. When it was found that there was inadequate interest among historians in Canada for an exhaustive examination of the Dieppe question, or even of a reconsideration of Canadian military operations in the Second World War, we decided to build a conference around the most active research under way in Canada. This meant that there was no theme as such, unless it could be called "The Second World War: Research in Canada Today". Even that would have been inaccurate because there was no way of including all aspects of such research, which is in various stages of development in this country, in one relatively small and intimate conference. -

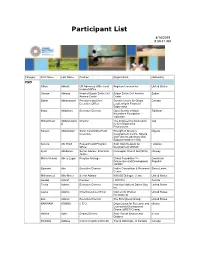

Participant List

Participant List 10/20/2020 12:59:08 PM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jamal Aazizi Chargé de la logistique Association Tazghart Morocco Luz Abayan Program Officer Child Rights Coalition Asia Philippines Babak Abbaszadeh President And Chief Toronto Centre For Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership In Financial Supervision Amr Abdallah Director, Gulf Programs Education for Employment - United States EFE Ziad Abdel Samad Executive Director Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development TAZI Abdelilah Président Associaion Talassemtane pour Morocco l'environnement et le développement ATED Abla Abdellatif Executive Director and The Egyptian Center for Egypt Director of Research Economic Studies Nabil Abdo MENA Senior Policy Oxfam International Lebanon Advisor Baako Abdul-Fatawu Executive Director Centre for Capacity Ghana Improvement for the Wellbeing of the Vulnerable (CIWED) Maryati Abdullah Director/National Publish What You Pay Indonesia Coordinator Indonesia Dr. Abel Executive Director Reach The Youth Uganda Switzerland Mwebembezi (RTY) Suchith Abeyewickre Ethics Education Arigatou International Sri Lanka me Programme Coordinator Diam Abou Diab Fellow Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Development Hayk Abrahamyan Community Organizer for International Accountability Armenia South Caucasus and Project Central Asia Aliyu Abubakar Secretary General Kano State Peace and Conflict Nigeria Resolution Association Sunil Acharya Regional Advisor, Climate Practical Action Nepal and Resilience Salim Adam Public Health -

Participant List

Participant List 4/14/2019 8:59:41 AM Category First Name Last Name Position Organization Nationality CSO Jillian Abballe UN Advocacy Officer and Anglican Communion United States Head of Office Osman Abbass Head of Sudan Sickle Cell Sudan Sickle Cell Anemia Sudan Anemia Center Center Babak Abbaszadeh President and Chief Toronto Centre for Global Canada Executive Officer Leadership in Financial Supervision Ilhom Abdulloev Executive Director Open Society Institute Tajikistan Assistance Foundation - Tajikistan Mohammed Abdulmawjoo Director The Engineering Association Iraq d for Development & Environment Kassim Abdulsalam Zonal Coordinator/Field Strength in Diversity Nigeria Executive Development Centre, Nigeria and Farmers Advocacy and Support Initiative in Nig Serena Abi Khalil Research and Program Arab NGO Network for Lebanon Officer Development (ANND) Kjetil Abildsnes Senior Adviser, Economic Norwegian Church Aid (NCA) Norway Justice Maria Victoria Abreu Lugar Program Manager Global Foundation for Dominican Democracy and Development Republic (GFDD) Edmond Abu Executive Director Native Consortium & Research Sierra Leone Center Mohammed Abu-Nimer Senior Advisor KAICIID Dialogue Centre United States Aouadi Achraf Founder I WATCH Tunisia Terica Adams Executive Director Hamilton National Dance Day United States Inc. Laurel Adams Chief Executive Officer Women for Women United States International Zoë Adams Executive Director The Strongheart Group United States BAKINAM ADAMU C E O Organization for Research and Ghana Community Development Ghana -

Finnish History Textbooks in the Cold War 249

The Cold War andthePoliticsofHistory The ColdWar The Cold War and the Politics of History explores selected themes on the role of history, historians and historical The Cold War debates during the Cold War, and the ways in which the Cold War still influences present day politics and our views of the past 20th century. and the Politics The authors of the volume look at how people from various countries and contexts viewed the conflict as of History history at the time and how history influenced their views of the conflict itself. They analyse how the Cold War was and still is present in symbols, popular representations and acts of commemoration in different parts of Europe, from Berlin to Budapest, from Tallinn to Tampere. The contributors of the book are leading scholars of contemporary European and international history and politics. The book is published on the occasion of Professor Seppo Hentilä’s, Chair of Political History at the University of Helsinki, 60th birthday. Edited by University of Helsinki Juhana Aunesluoma Department of Social Science History and Pauli Kettunen ISBN 978-952-10-4637-7 The Cold War and the Politics of History The Cold War and the Politics of History Edited by Juhana Aunesluoma & Pauli Kettunen Edita Publishing Ltd University of Helsinki Department of Social Science History Helsinki 2008 Edita Prima oy, Helsinki 2008 ISBN 978-952-10-4637-7 © 2008 authors and the Department of Social Science History Layout and cover: Klaus Lindgren Contents Preface 7 Pauli Kettunen and Juhana Aunesluoma: History in the Cold -

Finland in the World Media the Ministry for Foreign Affairs' Observations About 2020

Finland in the World Media The Ministry for Foreign Affairs' observations about 2020 New aspects of Finns as an innovative nation have come up in the US media due to the coronavirus pandemic. – THE UNITED STATES The Ministry for Foreign Affairs' observations about Finland in the world media This survey was designed to examine the topics associated with Finland in international media coverage. It comprised all media, with a particular focus on newspapers. The information is based on observations made by the embassies and missions. In most of the missions, media-related activities were conducted alongside other work; there are 38 members of staff in all the embassies and missions that submitted replies whose full-time job involves communications and boosting the image of Finland. The missions filled in the Webropol survey between December 2020 and January 2021. A total of 78 out of 89 missions responded to the survey. The missions' view of how Finland is rated in the world media The missions rated the media 2020 opinions about Finland from 4.25 critical (1) to admiring (5). In 2020, the average overall 2018 rating was 4.25. 4.07 2019 4.05 This was an improvement of 0.2 points on the previous year. The missions' views on words and themes related to Finland 2020 2019 2018 The most prominent themes The efficient handling and innovative treatment of the coronavirus pandemic drew positive attention The coronavirus pandemic turned eyes in Sweden to The way Finland handled the coronavirus pandemic was in Finland and its social system. [...] It was clear that the news from the spring, starting with emergency supplies, the Finnish government and society had done quite and in autumn the focus was on Finland's successful strategy well in the coronavirus stress test: Finland’s citizens to control the second wave of the pandemic, especially as were protected and its society's laws and processes Finland's strategy was very different from Sweden's. -

Supporting Women, Protecting Rights Seminar

SEMINAR REPORT SUPPORTING WOMEN, PROTECTING RIGHTS How can the EU work to better safeguard the work of WHRDs and integrate an intersectional approach. in cooperation with European Parliament Liaison Office and KIOS Foundation 1 Seminar Report – Supporting Women, Protecting Rights AMNESTY INTERNATIONAL EXPERTS’ SEMINAR IN COOPERATION WITH KIOS FOUNDATION AND EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT LIAISON OFFICE AT EUROOPPASALI 29th AUGUST 2019, HELSINKI 2 Seminar Report – Supporting Women, Protecting Rights CONTENT Summary 5 Foreword 6 Seminar introduction 7 Opening remarks by Minister for Foreign Affairs of Finland, Pekka Haavisto 9 Greetings from Vienna by María Teresa Rivera 11 Panel: EU and member states’ protection and support to WHRDs globally 13 Panel: Smear campaigns and hate speech/attacks against WHRDs 19 Recommendations by the Amnesty International 27 Gymnich lunch 29 Concluding remarks 32 Ideas and recommendations 33 BIOS of WHRDs and other speakers 37 3 Seminar Report – Supporting Women, Protecting Rights Last photo of the page: Lauri Heikkinen/Prime Minister’s Office, Finland 4 Seminar Report – Supporting Women, Protecting Rights Summary On 29th August 2019 – on the first day of the informal “Gymnich” meeting of European Union (EU) Foreign Affairs Ministers in Helsinki − the Finnish Section of Amnesty International hosted a seminar entitled “Supporting Women, Protecting Rights - How can the EU work better to safeguard the work of WHRDs and integrate an intersectional approach”. The seminar brought together women human rights defenders (WHRDs) from El Salvador, Finland, Russia, Uganda, Bahrain and Ukraine to discuss how the EU Guidelines on Human Rights De- fenders could be implemented more effectively together with civil society representatives, government and EU and member state officials, how the guidelines could support women human rights defenders and what kind of threats women human rights defenders are currently facing. -

The Finnish Approach, Within the EU Framework, to Lead the Transition Into a Circular Economy

A thesis submitted to the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy of Central European University in part fulfilment of the Degree of Master of Science The Finnish approach, within the EU framework, to lead the transition into a Circular Economy CEU eTD Collection Carolina Andrea RODRÍGUEZ BALDA October, 2020 Budapest Notes on copyright and the ownership of intellectual property rights: (1) Copyright in text of this thesis rests with the Author. Copies (by any process) either in full, or of extracts, may be made only in accordance with instructions given by the Author and lodged in the Central European University Library. Details may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. Further copies (by any process) of copies made in accordance with such instructions may not be made without the permission (in writing) of the Author. (2) The ownership of any intellectual property rights which may be described in this thesis is vested in the Central European University, subject to any prior agreement to the contrary, and may not be made available for use by third parties without the written permission of the University, which will prescribe the terms and conditions of any such agreement. (3) For bibliographic and reference purposes this thesis should be referred to as: Rodríguez, C. 2020. The Finnish approach, within the EU framework, to lead the transition into a Circular Economy. Master of Science thesis, Central European University, Budapest. Further information on the conditions under which disclosures and exploitation may take place is available from the Head of the Department of Environmental Sciences and Policy, Central European University. -

Abuse of Power: Coordinated Online Harassment of Finnish Government Ministers

978-9934-564-97-0 !%^#@ D!@ B@*h F*%# ABUSE OF POWER: COORDINATED ONLINE HARASSMENT OF FINNISH GOVERNMENT MINISTERS Published by the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence ISBN: 978-9934-564-97-0 Project manager: Rolf Fredheim Authors: Kristina Van Sant, Rolf Fredheim, and Gundars Bergmanis-Korāts Copy-editing: Anna Reynolds Design: Kārlis Ulmanis Riga, February 2021 NATO STRATCOM COE 11b Kalnciema Iela Riga LV1048, Latvia www.stratcomcoe.org Facebook/stratcomcoe Twitter: @stratcomcoe This report was completed in November 2020, and based on data collected from March to July 2020 This publication does not represent the opinions or policies of NATO or NATO StratCom COE. © All rights reserved by the NATO StratCom COE. Reports may not be copied, reproduced, distributed or publicly displayed without reference to the NATO StratCom COE. The views expressed here do not represent the views of NATO. PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY The main topics triggering abusive messages were the COVID-19 pandemic, immigration, Finnish-EU relations, and socially liberal politics. Executive Summary This report is an explorative analysis a period spanning the state of emergency of abusive messages targeting Finnish declared in response to the COVID-19 ministers on the social media platform pandemic.1 Twitter. The purpose of this study is to understand the scope of politically This report is informed by the findings of motivated abusive language on Finnish three recent Finnish studies, one of which Twitter, and to determine if, and to what investigated the extent and effects of online extent, it is perpetrated by inauthentic hate speech against politicians while the accounts. -

Current Affairs Q&A

Current Affairs Q&A PDF This is Paid PDF provided by AffairsCloud.com, Our team is working hard in back end to provide quality PDF. If you not buy this paid PDF subscription plan, we kindly request you to buy pdf to avail this service. Help Us To Grow & Provide Quality Service CURRENT AFFAIRS PDF PLANS Current Affairs PDF 2019: Study, Pocket and Q&A PDF’s Current Affairs PDF 2018: Study, Pocket and Q&A PDF’s CRACK HIGH LEVEL PDF PLANS Crack High Level: Puzzle & Seating Arrangement Questions PDF 2019 Crack High Level: English Language Questions PDF 2019 Crack High Level: Data Interpretation Questions PDF 2019 Suggestions& Feedback are welcomed – https://www.affairscloud.com/subscriber-feedback/ 1 | Page Report Errors in the PDF - [email protected] Copyright 2019 @ AffairsCloud.Com Current Affairs Q&A PDF Current Affairs Q&A PDF - Dec (1-14), 2019 Table of Contents Current Affairs Q&A PDF - Dec (1-14), 2019 ................................................................................................................. 2 INDIAN AFFAIRS ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 STATE NEWS ................................................................................................................................................................. 41 INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS ........................................................................................................................................... 49 BANKING