Val Smith Introduction in the Attics of Achnacarry, Hereditary Home of the Camerons of Lochiel, Are Many Hidden Treasures Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Loch Arkaig Land Management Plan Summary

Loch Arkaig Land Management Plan Summary Loch Arkaig Forest flanks the Northern and Southern shores of Loch Arkaig near the hamlets of Clunes and Achnacarry, 15km North of Fort William. The Northern forest blocks are accessed by a minor dead end public road. The Southern blocks are accessed by boat. This area is noted for the fishing, but more so for its link with the training of commandos for World War II missions. The Allt Mhuic area of the forest is well known for its invertebrates such as the Chequered Skipper butterfly. Loch Arkaig LMP was approved on 19/10/2010 and runs for 10 years. What’s important in the new plan: Gradual restoration of native woodland through the continuation of a phased clearfell system Maximisation of available commercial restocking area outwith the PAWS through keeping the upper margin at the altitude it is at present and designing restock coupes to sit comfortably within the landscape Increase butterfly habitat through a network of open space and expansion of native woodland. Enter into discussions with Achnacarry Estate with the aim of creating a strategic timber transport network which is mutually beneficial to the FC and the Estate, with the aim of facilitating the harvesting of timber and native woodland restoration from the Glen Mallie and South Arkaig blocks. The primary objectives for the plan area are: Production of 153,274m3 of timber Restoration of 379 ha of native woodland following the felling of non- native conifer species on PAWS areas To develop access to the commercial crops to enable harvesting operations on the South side of Loch Arkaig To restock 161 ha of commercial productive woodland. -

Appeal Citation List External

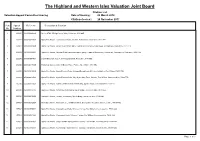

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Joint Board Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 08 March 2018 Citations Issued : 24 November 2017 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 265435 01/05/394028/8 Site for ATM , 55 High Street, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4NE 2 268844 03/02/002650/4 Hydro Elec Works , Loch Rosque Hydro Scheme, Achnasheen, Ross-shire, IV22 2ER 3 268842 03/03/083400/9 Hydro Elec Works , Allt an Ruigh Mhoir Hydro, Heights of Kinlochewe, Kinlochewe, Achnasheen, Ross-shire, IV22 2 PA 4 268839 03/03/083600/7 Hydro Elec Works , Abhainn Srath Chrombaill Upper Hydro, Heights of Kinlochewe, Kinlochewe, Achnasheen, Ross-shire, IV22 2 PA 5 262235 03/09/300105/1 Depot (Miscellaneous), Ferry Road, Dingwall, Ross-shire, IV15 9QS 6 262460 04/06/031743/0 Workshop (Commercial), 3A Broom Place, Portree, Isle of Skye, IV51 9HL 7 268835 05/03/001900/4 Hydro Elec Works , Hydro Electric Works, Outward Bound Locheil Centre, Achdalieu, Fort William, PH33 7NN 8 268828 05/03/081950/3 Hydro Elec Works , Hydro Electric Works, Moy Hydro, Moy Farm, Banavie, Fort William, Inverness-shire, PH33 7PD 9 260730 05/03/087560/2 Hydro Elec Works , Rubha Cheanna Mhuir, Achnacarry, Spean Bridge, Inverness-shire, PH34 4EL 10 260728 05/03/087570/5 Hydro Elec Works , Achnasaul, Achnacarry, Spean Bridge, Inverness-shire, PH34 4EL 11 260726 05/03/087580/8 Hydro Elec Works , Arcabhi, Achnacarry, Spean Bridge, Inverness-shire, PH34 4EL 12 257557 05/06/023250/7 Hydro Elec Works , Hydro Scheme, Allt Eirichaellach, Glenquoich, -

Spean Bridge Primary School School Handbook 2021/22

SPEAN BRIDGE PRIMARY SCHOOL SCHOOL HANDBOOK 2021/22 1 CONTENTS PAGE NUMBER Letter of Welcome 3 General Information and Staff 4 Spean Bridge School Aims 5 About Spean Bridge Primary 6 -9 Classes and Nursery 10 Enrolment / Placing Requests 11 Transport / Uniform / PE 12 Indoor Shoes / Newsletters /Absences 13 Contact Information / Website/ 14 Schools Information Service School Meals 15 Fruit Tuck Shop / School Milk / Mobile 16 Phones /Parking Parents as Partners 16 - 17 Citizenship Groups / Assemblies 18 School Garden 19 - 20 Extra-Curricular Activities 21 Residential Trips / Health 22 Child Protection 23 Behaviour and Discipline 24 - 25 General Guidance / Parent Council 26 Curriculum and Assessment 27 - 30 Additional Support Needs 31 - 33 The Curriculum 34 - 39 Homework 40 - 42 School Policies / Holiday Dates / 43 Suggestions, Concerns and Complaints Self-Evaluation / Data Protection 44 - 45 Equality and Inclusion 46 2 The current pandemic has affected the normal running of schools in many ways. This Handbook reflects the way the school usually runs but does not cover all of the changes that we have made because of the pandemic. Our arrangements have changed in many ways this session, and may well change again, depending on how the pandemic develops. For the most up-to-date information about any aspect of the work of the school, please make contact and we will be able to tell you about our current arrangements. For the latest information about how the pandemic affects children, young people and families across Scotland, please visit the Scottish Government website, which has helpful information about Coronavirus and its impact on education and children. -

The Clan Gillean

Ga-t, $. Mac % r /.'CTJ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://archive.org/details/clangilleanwithpOOsinc THE CLAN GILLEAN. From a Photograph by Maull & Fox, a Piccadilly, London. Colonel Sir PITZROY DONALD MACLEAN, Bart, CB. Chief of the Clan. v- THE CLAN GILLEAN BY THE REV. A. MACLEAN SINCLAIR (Ehartottftcton HASZARD AND MOORE 1899 PREFACE. I have to thank Colonel Sir Fitzroy Donald Maclean, Baronet, C. B., Chief of the Clan Gillean, for copies of a large number of useful documents ; Mr. H. A. C. Maclean, London, for copies of valuable papers in the Coll Charter Chest ; and Mr. C. R. Morison, Aintuim, Mr. C. A. McVean, Kilfinichen, Mr. John Johnson, Coll, Mr. James Maclean, Greenock, and others, for collecting- and sending me genea- logical facts. I have also to thank a number of ladies and gentlemen for information about the families to which they themselves belong. I am under special obligations to Professor Magnus Maclean, Glasgow, and Mr. Peter Mac- lean, Secretary of the Maclean Association, for sending me such extracts as I needed from works to which I had no access in this country. It is only fair to state that of all the help I received the most valuable was from them. I am greatly indebted to Mr. John Maclean, Convener of the Finance Committee of the Maclean Association, for labouring faithfully to obtain information for me, and especially for his efforts to get the subscriptions needed to have the book pub- lished. I feel very much obliged to Mr. -

Whm 2015 News

TAIGH-TASGAIDH NA GAIDHEALTACHD AN IAR NEWSLETTER DECEMBER 2015 Message Message from the Manager You will be pleased to know we have had a good year so far from the at the Museum. Our visitor numbers, shop sales and donations from visitors are all up slightly on last year’s figures. This was partly achieved by opening 8 Sundays Chairman during the summer. We opened from 11am to 3pm and had over 1000 visitors over the 8 weeks we opened. We plan to do the same next year. No matter what we might think of our We have had an eventful year here at West Highland own endeavours, it’s how we affect Museum. The two most memorable events for me were our others and how we appear to them members and friends visit to Roshven House; and my first visit to an auction house with that’s important. “To see oursels as Sally Archibald. ithers see us”, is Burns’ oft-quoted In May, Angus MacDonald very kindly opened his house to our members and their friends. It was a grand day out and raised £813 for museum funds. There is more about line. We live in the time of peer- this event in the newsletter. review; and for us achieving Full Also in May, Sally Archibald and I Accreditation from Museum Galleries attended the Jacobite, Stuart & Scotland in October was certainly a Scottish Applied Arts auction at Lyon ringing endorsement from our sector. and Turnbull’s auction house in Edinburgh. This was my first visit to Less formal, though just as important, an auction house and I found it really are our regular excellent reviews on good fun. -

Achnacarry at War” August 2012

The Magazine of Clan Cameron New Zealand Inc. Photo: Bill Cameron A summer picture of Corpach and the Caledonian Canal with Ben Inside…. Nevis in the background Lochiel talks about Vol 46 No 4 “Achnacarry at War” August 2012 Photo: Editor Another mountain far removed from the Ben. A Winter view of Mount Ruapehu from the Robert will talk about Desert Road taken in 2008 while driving himself and his music First Lighter Robert Nairn south to Turakina in a future issue Photos: Editor My next official visit is to the Auckland annual dinner in August. This will be another enjoyable occasion for all and we A message from our President hope they will have a good attendance. Tristan may have to apologise as his kids will be coming on at the goat farm, but we are To all Clan members. trying to get a talk together to be presented on the evening. Once again it is time for another Regards to all, newsletter and to tell you what Fraser 15.7.2012 we have been doing since the last issue. We had to apologise to Coming Events Manawatu for not being able to attend their annual dinner, but it Sunday 5 August 2012 Hawkes Bay Branch lunch was disappointing to find they A lunch outing is planned for at No 5 Cafe / Larder at the Driving Range had cancelled due to lack of on Karamu Rd/Highway 2 Maungateretere. Members to let Helen Shaw numbers. This was also what know by Wednesday 1st August if they are attending please. -

Glenmallie and South Loch Arkaig Forests Draft Community Forest

Appendix 6 Glenmallie and South Loch Arkaig Forests Draft Community Forest Management Plan Prepared on behalf of Achnacarry, Bunarkaig & Clunes Group (ABC Group) in support of their application to purchase Glenmallie and South Loch Arkaig Forests under the National Forest Land Scheme. Jamie Mcintyre and Gary Servant with the support of the ABC Forestry/Renewables Steering Group February 2014 Executive Summary This report outlines the nature of the forest blocks of Glenmallie and South Loch Arkaig, which are being disposed of by FCScotland under the 'National Forest Land Scheme: Sponsored Sale of Surplus Land'. It further outlines the process of local decision making which has taken place over the past four months to arrive at this point, and makes a number of firm business-planning proposals to take forward the process of community acquisition and management of a substantial and potentially challenging forest containing a mixture of native pinewood remnants, other native woodland habitats and non-native conifers. Initial projections suggest that forest management could support around 2 full time equivalent posts in the forestry/land management sector, and if successful in overcoming the very significant challenges of the site then the harvesting and marketing of the commercial timber could generate a significant net income to the community by year 5 of the project. The report is designed initially to complement the ABC Group NFLSapplication to Forestry Commission Scotland, and should be read in conjunction with the 12 Appendices listed in Section 9 below. 2 'Fully a quarter mile west of the waterfall, a rough road branches off to the left and is bridged over the River Arkaig where this river leaves the loch of the same name. -

7-Night Scottish Highlands Gentle Guided Walking Holiday

7-night Scottish Highlands Gentle Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Gentle Walks Destinations: Scottish Highlands & Scotland Trip code: LLBEW-7 1, 2 & 3 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Glen Coe is arguably one of the most celebrated glens in the world with its volcanic origins, and its dramatic landscapes offering breathtaking scenery – magnificent peaks, ridges and stunning seascapes. This easier variation of our best-selling Guided Walking holidays is the perfect way to enjoy a gentle exploration of the Scottish Highlands. Easy walks of 3-4 miles with up to 400 feet of ascent are available, although if you’d like to do something a bit more demanding walks up some of the lower hills are also included in the programme. Our medium option walks are 6 to 8 miles with up to 1000 feet of ascent whilst harder options are 8 to 10 miles with up to 2,600 feet of ascent. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our Country House • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Discover the dramatic scenery of the Scottish Highlands • Explore the atmospheric glens and coastal paths seeking out the best viewpoints. • Hear about the turbulent history of the highlands • Join our friendly and knowledgeable guides who will bring this stunning landscape to life TRIP SUITABILITY This trip is graded Activity Level 1, 2 and 3. This easier variation of our best-selling Guided Walking holidays is the perfect way to enjoy a gentle exploration of the Scottish Highlands. -

Local Community Support Services

LOCAL COMMUNITY SUPPORT SERVICES During the present coronavirus (COVID-19) crisis, help is available from a range of local services for: • Shopping • Transport • Medication and errand pick-ups • Giving a friendly local voice and support VOLUNTARY ACTION LOCHABER and CARE LOCHABER can both help with delivering shopping and prescriptions. VOLUNTARY ACTION LOCHABER HELPLINE: 01397 719514 (Mon-Fri 10am-4pm) We are also offering a “Plugging the Gaps” service to help ensure Lochaber residents who are not accessing assistance from any established groups can be supported by one of our volunteers or sign-posted to an appropriate service. CARE LOCHABER: 01397 701222 (Mon-Fri 9am-2pm) TIME 2 CHAT TELEPHONE BEFRIENDING SERVICE The Rotary Club of Lochaber have partnered with Voluntary Action Lochaber to deliver a telephone befriending service for those who are suffering from isolation or loneliness throughout the Covid 19 crisis. If you or anyone you know would like to access the service please contact: 01397 719511 LOCHABER HOPE is offering online support via Zoom video calls as well as a range of other support. 01397 704836 or email [email protected] EWEN’S ROOM is running ‘EWENME’, a helpline aimed at connecting people and reducing loneliness and social isolation. Call 01967 750845 or fill in the form at www.ewensroom.com/ewenme/ HIGHLAND COUNCIL - FREE HELPLINES The Highland Council has a dedicated number 01349 886669 for those that have received Shielding letters or texts. It also has a second free helpline to give assistance and to collect details of individuals and community groups looking to provide volunteering support during the coronavirus (COVID- 19) outbreak. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Commando Country Special training centres in the Scottish highlands, 1940-45. Stuart Allan PhD (by Research Publications) The University of Edinburgh 2011 This review and the associated published work submitted (S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing) have been composed by me, are my own work, and have not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. Stuart Allan 11 April 2011 2 CONTENTS Abstract 4 Critical review Background to the research 5 Historiography 9 Research strategy and fieldwork 25 Sources and interpretation 31 The Scottish perspective 42 Impact 52 Bibliography 56 Appendix: Commando Country bibliography 65 3 Abstract S. Allan, 2007. Commando Country. Edinburgh: NMS Enterprises Publishing. Commando Country assesses the nature of more than 30 special training centres that operated in the Scottish highlands between 1940 and 1945, in order to explore the origins, evolution and culture of British special service training during the Second World War. -

Spean Bridge, Roy Bridge and Achnacarry Community Council

1 q SPEAN BRIDGE, ROY BRIDGE AND ACHNACARRY COMMUNITY COUNCIL Page 1 8th November 2018 18/04647/FUL | Proposal to construct and operate a run-of-river Hydro scheme (Scheme 3 - Allt Coire an Eoin) | Land 685M SE Of Nevis Range Torlundy Fort William 18/04648/FUL | Proposal to construct and operate a run-of-river hydro scheme (Scheme 5 - Allt Leachdach and Allt Beinn Chlianaig) | Leanachan Forest Torlundy Fort William 18/04649/FUL | Installation of hydro-electricity scheme, including intake structure, buried pipeline, powerhouse, borrow pits, construction compounds, laydown and storage areas, bridge and access tracks - Allt na Lairige | Land To West Of Allt Na Lairige 7220M NW Of Station House Corrour. Spean Bridge, Roy Bridge and Achnacarry Community Council support GFG Alliance’s vision to maximise the existing smelter’s output, and build an alloy wheel manufacturing facility utilising new sources of renewable energy. Such activity coupled with enhanced support facilities should provide much needed new employment, housing, infrastructure and leisure opportunities for the communities of Lochaber and beyond. Whilst recognizing the benefits of these proposals they cannot be at any cost and we have some reservations about the Developer based on past and present performance. SIMEC GHR prior to their acquisition by GFG Alliance planned and constructed a similar series of Micro Hydro Schemes in Loch Arkaig. They received a glowing testimony from a local group at the application stage, but the construction phase was anything but straightforward. There were numerous complaints about inappropriate behaviour by contractors, the lifeline access B8005 was often closed to recover HGV’s from ditches in the Dark Mile and there were outages and electricity supply difficulties for residents during the grid connection phase. -

Microsoft Outlook

Tim Stott From: West Highlands and Islands Local Development Plan Subject: FW: West Highland and Islands Local Development Plan [#52] Section 1: Your personal and contact details Martin Balcombe 1.1 Name * Select a topic to comment on Comment on Fort William Hinterland boundary Protection Site 1 Farmland bordered by the B8004 (to south), Loch Lochy-Mucomir cut 3.1 Address / Description of Land (to east), Loch Lochy (to North) and Gairlochy village & Caledonian Canal (to west) 3.2 Landowner's name (if known) Mr R. Anderson 3.4 Why should the land be protected? This is an area that floods and the landscape would not cope with development without causing even greater flooding problems to the local housing. Protection Site 2 The immediate vicinity of the Caledonian Canal – Gairlochy, from the 3.5 Address / Description of Land B8004 bridge to the Loch Lochy Lighthouse 3.6 Landowner's name (if known) Scottish Canals 3.8 Why should the land be protected? This land is valued by the wider local community and visitors to the area for scenic walking and should not be developed further than it is already Next Return to contents 6.1 Name of Special Landscape Area Loch Lochy and Loch Oich 6.2 Tell us whether this special landscape I wish to support the inclusion of all the areas within the current area should stay the same or how it should boundary and ask that the area should not be contracted, particularly be expanded / contracted. Please provide in the area of Gairlochy, Bunarkaig, Clunes and Achnacarry.