The Catholic University of America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

St. Margaret's in Eastcheap

ST. MARGARET'S IN EASTCHEAP NINE HUNDRED YEARS OF HISTORY A Lecture delivered to St. Margaret's Historical Society on January 6th, 1967 by Dr. Gordon Huelin "God that suiteth in Trinity, send us peace and unity". St. Margaret's In Eastcheap : Nine hundred years of History. During the first year of his reign, 1067, William the Conqueror gave to the abbot and church of St. Peter's, Westminster, the newly-built wooden chapel of St. Margaret in Eastcheap. It was, no doubt, with this in mind that someone caused to be set up over the door of St. Margaret Pattens the words “Founded 1067”. Yet, even though it seems to me to be going too far to claim that a church of St. Margaret's has stood upon this actual site for the last nine centuries, we in this place are certainly justified in giving' thanks in 1967 for the fact that for nine hundred years the faith has been preached and worship offered to God in a church in Eastcheap dedicated to St. Margaret of Antioch. In the year immediately following the Norman Conquest much was happening as regards English church life. One wishes that more might be known of that wooden chapel in Eastcheap, However, over a century was to elapse before even a glimpse is given of the London churches-and this only in general terms. In 1174, William Fitzstephen in his description of London wrote that “It is happy in the profession of the Christian religion”. As regards divine worship Fitzstephen speaks of one hundred and thirty-six parochial churches in the City and suburbs. -

John Leland's Itinerary in Wales Edited by Lucy Toulmin Smith 1906

Introduction and cutteth them out of libraries, returning home and putting them abroad as monuments of their own country’. He was unsuccessful, but nevertheless managed to John Leland save much material from St. Augustine’s Abbey at Canterbury. The English antiquary John Leland or Leyland, sometimes referred to as ‘Junior’ to In 1545, after the completion of his tour, he presented an account of his distinguish him from an elder brother also named John, was born in London about achievements and future plans to the King, in the form of an address entitled ‘A New 1506, probably into a Lancashire family.1 He was educated at St. Paul’s school under Year’s Gift’. These included a projected Topography of England, a fifty volume work the noted scholar William Lily, where he enjoyed the patronage of a certain Thomas on the Antiquities and Civil History of Britain, a six volume Survey of the islands Myles. From there he proceeded to Christ’s College, Cambridge where he graduated adjoining Britain (including the Isle of Wight, the Isle of Man and Anglesey) and an B.A. in 1522. Afterwards he studied at All Souls, Oxford, where he met Thomas Caius, engraved map of Britain. He also proposed to publish a full description of all Henry’s and at Paris under Francis Sylvius. Royal Palaces. After entering Holy Orders in 1525, he became tutor to the son of Thomas Howard, Sadly, little or none of this materialised and Leland appears to have dissipated Duke of Norfolk. While so employed, he wrote much elegant Latin poetry in praise of much effort in seeking church advancement and in literary disputes such as that with the Royal Court which may have gained him favour with Henry VIII, for he was Richard Croke, who he claimed had slandered him. -

Chaucer’S Birth—A Book Went Missing

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. •CHAPTER 1 Vintry Ward, London Welcome, O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience. — James Joyce, Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man In the early 1340s, in Vintry Ward, London— the time and place of Chaucer’s birth— a book went missing. It wasn’t a very important book. Known as a ‘portifory,’ or breviary, it was a small volume containing a variety of excerpted religious texts, such as psalms and prayers, designed to be carried about easily (as the name demonstrates, it was portable).1 It was worth about 20 shillings, the price of two cows, or almost three months’ pay for a carpenter, or half of the ransom of an archer captured by the French.2 The very presence of this book in the home of a mer- chant opens up a window for us on life in the privileged homes of the richer London wards at this time: their inhabitants valued books, ob- jects of beauty, learning, and devotion, and some recognized that books could be utilized as commodities. The urban mercantile class was flour- ishing, supported and enabled by the development of bureaucracy and of the clerkly classes in the previous century.3 While literacy was high in London, books were also appreciated as things in themselves: it was 1 Sharpe, Calendar of Letter- Books of the City of London: Letter- Book F, fol. -

Glaven Historian

the GLAVEN HISTORIAN No 16 2018 Editorial 2 Diana Cooke, John Darby: Land Surveyor in East Anglia in the late Sixteenth 3 Jonathan Hooton Century Nichola Harrison Adrian Marsden Seventeenth Century Tokens at Cley 11 John Wright North Norfolk from the Sea: Marine Charts before 1700 23 Jonathan Hooton William Allen: Weybourne ship owner 45 Serica East The Billyboy Ketch Bluejacket 54 Eric Hotblack The Charities of Christopher Ringer 57 Contributors 60 2 The Glaven Historian No.16 Editorial his issue of the Glaven Historian contains eight haven; Jonathan Hooton looks at the career of William papers and again demonstrates the wide range of Allen, a shipowner from Weybourne in the 19th cen- Tresearch undertaken by members of the Society tury, while Serica East has pulled together some his- and others. toric photographs of the Billyboy ketch Bluejacket, one In three linked articles, Diana Cooke, Jonathan of the last vessels to trade out of Blakeney harbour. Hooton and Nichola Harrison look at the work of John Lastly, Eric Hotblack looks at the charities established Darby, the pioneering Elizabethan land surveyor who by Christopher Ringer, who died in 1678, in several drew the 1586 map of Blakeney harbour, including parishes in the area. a discussion of how accurate his map was and an The next issue of Glaven Historian is planned for examination of the other maps produced by Darby. 2020. If anyone is considering contributing an article, Adrian Marsden discusses the Cley tradesmen who is- please contact the joint editor, Roger Bland sued tokens in the 1650s and 1660s, part of a larger ([email protected]). -

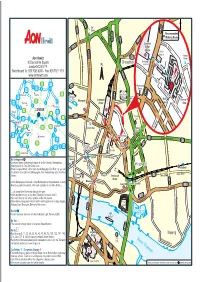

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

Cutlers Court, 115 Houndsditch, London, EC3A 7BR 2,345 to 9,149 Sq Ft

jll.co.uk/property To Let Cutlers Court, 115 Houndsditch, London, EC3A 7BR 2,345 to 9,149 sq ft • Cost effective fitted out offices • Furniture packages available • Flexible working space • Manned reception Location EPC The building is located on the north side of Houndsditch. 115 This property has been graded as E (122). Houndsditch benefits from excellent access to public transport being 3 minutes from Liverpool Street station, 4 minutes from Rent Aldgate tube station and 8 minutes from Bank Station. The £19.50 per sq ft property is situated within close proximity to Lloyd’s of London exclusive of rates, service charge and VAT (if applicable). and Broadgate and is moments from the amenities of Devonshire Square and Spitalfields. Business Rates Rates payable: £14.77 per sq ft Specification The Ground and 4th floors are available with high quality fit Service Charge outs in situ as follows: £11.85 per sq ft Ground floor EC3A 7BR - 1 x 8 person meeting room - 1 x 6 person meeting room - 1 x 4 person meeting room - Kitchen/breakout area - Cat 6 Data Cabling 4th floor - 1 x 10 person meeting room - 2 x 8 person meeting rooms - 2 on floor showers - Kitchen/breakout area - New floor outlet boxes and underfloor CAT 6 data cabling Terms New lease available from the Landlord (term certain until June Contacts 2023). Nick Lines 0207 399 5693 Viewings [email protected] Viewing via the sole agents only. Nick Going Accommodation [email protected] Floor/Unit Sq ft Rent Availability 4th 6,804 £19.50 per sq ft Available Ground 2,345 £19.50 per sq ft Available Total 9,149 JLL for themselves and for the vendors or lessors of this property whose agents they are, give notice that:- a. -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

Native Fish Conservation

Yellowstone SScience Native Fish Conservation @ JOSH UDESEN Native Trout on the Rise he waters of Yellowstone National Park are among the most pristine on Earth. Here at the headwaters of the Missouri and Snake rivers, the park’s incredibly productive streams and lakes support an abundance of fish. Following the last Tglacial period 8,000-10,000 years ago, 12 species/subspecies of fish recolonized the park. These fish, including the iconic cutthroat trout, adapted and evolved to become specialists in the Yellowstone environment, underpinning a natural food web that includes magnificent animals: ospreys, bald eagles, river otters, black bears, and grizzly bears all feed upon cutthroat trout. When the park was established in 1872, early naturalists noted that about half of the waters were fishless, mostly because of waterfalls which precluded upstream movement of recolonizing fishes. Later, during a period of increasing popularity of the Yellowstone sport fishery, the newly established U.S. Fish Commission began to extensively stock the park’s waters with non-natives, including brown, brook, rainbow, and lake trout. Done more than a century ago as an attempt to increase an- gling opportunities, these actions had unintended consequences. Non-native fish caused serious negative impacts on native fish populations in some watersheds, and altered the parks natural ecology, particularly at Yellowstone Lake. It took a great deal of effort over many decades to alter our native fisheries. It will take a great deal more work to restore them. As Aldo Leopold once said, “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic com- munity. -

Liverpool Street Bus Station Closure

Liverpool Street bus station closed - changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 and N133 The construction of the new Crossrail ticket hall in Liverpool Street is progressing well. In order to build a link between the new ticket hall and the Underground station, it will be necessary to extend the Crossrail hoardings across Old Broad Street. This will require the temporary closure of the bus station from Sunday 22 November until Spring 2016. Routes 11, 23 and N11 Buses will start from London Wall (stop ○U) outside All Hallows Church. Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn right at the traffic lights. The last stop for buses towards Liverpool Street will be in Eldon Street (stop ○V). From there it is 50 metres to the steps that lead down into the main National Rail concourse where you can also find the entrance to the Underground station. Buses in this direction will also be diverted via Princes Street and Moorgate, and will not serve Threadneedle Street or Old Broad Street. Routes 133 and N133 The nearest stop will be in Wormwood Street (stop ○Q). Please walk down Old Broad Street and turn left along Wormwood Street after using the crossing to get to the opposite side of the road. The last stop towards Liverpool Street will also be in Wormwood Street (stop ○P). Changes to routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 Routes 11, 23, 133, N11 & N133 towards Liverpool Street Routes 11 & N11 towards Bank, Aldwych, Victoria and Fulham Route 23 towards Bank, Aldwych, Oxford Circus and Westbourne Park T E Routes 133 & N133 towards London Bridge, Elephant & Castle, -

Some Named Brewhouses in Early London Mike Brown

Some named brewhouses in early London Mike Brown On the river side, below St. Katherine's, says ed to be somewhat dispersed through a Pennant, on we hardly know what authority, variety of history texts. Members will be stood, in the reign of the Tudors, the great aware that the Brewery History Society breweries of London, or the "bere house," as has gradually been covering the history it is called in the map of the first volume of of brewing in individual counties, with a the "Civitates Orbis." They were subject to series of books. Some of these, such as the usual useful, yet vexatious, surveillance Ian Peaty's Essex and Peter Moynihan's of the olden times; and in 1492 (Henry VII.) work on Kent, have included parts of the king licensed John Merchant, a Fleming, London in the wider sense ie within the to export fifty tuns of ale "called berre;" and in M25. There are also histories of the main the same thrifty reign one Geffrey Gate concerns eg Red Barrel on Watneys, but (probably an officer of the king's) spoiled the they often see the business from one par- brew-houses twice, either by sending abroad ticular perspective. too much beer unlicensed, or by brewing it too weak for the sturdy home customers. The Hence, to celebrate the Society’s 40th demand for our stalwart English ale anniversary and to tie in with some of the increased in the time of Elizabeth, in whose events happening in London, it was felt reign we find 500 tuns being exported at one that it was time to address the question time alone, and sent over to Amsterdam of brewing in the capital - provisionally probably, as Pennant thinks, for the use of entitled Capital Ale or similar - in a single our thirsty army in the Low Countries. -

FWS/OBS-77/62 September 1977 an EVALUATION of the STATUS, LIFE HISTORY, and HABITAT REQUIREMENTS of ENDANGERED and THREATENED FI

FWS/OBS-77/62 September 1977 AN EVALUATION OF THE STATUS, LIFE HISTORY, AND HABITAT REQUIREMENTS OF ENDANGERED AND THREATENED FISHES OF THE UPPER COLORADO RIVER SYSTEM By Timothy W. Joseph, Ph. D. James A. Sinning, M.S. ECOLOGY CONSULTANTS, INC. 1716 Heath Parkway Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 Co-authors Robert J. Behnke, Ph. D. Colorado State University Paul B. Holden, Ph. D. Biowest Western Water Allocation Project Funds Interagency Agreement Number Contract Number EPA-IAG-D7-E685 14-16-0009-77-012 Mr. Clinton Hall, Director Carl Armour, Project Officer Energy Coordination Staff Western Energy and Land Use Team Office of Energy, Minerals 2625 Redwing Road and Industry Fort Collins, Colorado 80526 Environmental Protection Agency Washington, D. C. 20460 This study was conducted as part of the Federal Interagency Energy/Enviromlntal Research and Development Program U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Performed for Western Energy and Land Use Team Office of Biological Services Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TABLE OF CONTENTS Page PREFACE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS viii INTRODUCTION 1 I. ABIOTIC COMPONENTS 7 Introduction 7 Annual Discharge 9 Depletions 9 Irrigation Use 11 Transmountain Exports 12 Reservoir Evaporation 14 Other Uses 17 Analyses of Historic Records 18 Salinity 28 Sediment 29 Temperature 32 pH 33 Dissolved Oxygen 34 Other Water Quality Parameters 35 II. BIOLOGICAL COMPONENTS 42 Introduction 42 Primary Producers 42 Invertebrates 44 Fishes 45 III. SPECIES DESCRIPTIONS 47 Introduction 47 Colorado Squawfish 54 Humpback Chub 61 Razorback Sucker 65 Bonytail Chub 70 Colorado River Cutthroat Trout 74 Kendall Warm Springs Dace 80 Roundtail Chub 82 Piute Sculpin 86 Mottled Sculpin 87 Flannelmouth Sucker 88 Mountain Whitefish 90 Speckled Dace 91 Mountain Sucker 92 Bluehead Sucker 93 iii IV. -

A Fifteenth-Century Merchant in London and Kent

MA IN HISTORICAL RESEARCH 2014 A FIFTEENTH-CENTURY MERCHANT IN LONDON AND KENT: THOMAS WALSINGHAM (d.1457) Janet Clayton THOMAS WALSINGHAM _______________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS 3 Chapter 1 INTRODUCTION 4 Chapter 2 THE FAMILY CIRCLE 10 Chapter 3 CITY AND CROWN 22 Chapter 4 LONDON PLACES 31 Chapter 5 KENT LEGACY 40 Chapter 6 CONCLUSION 50 BIBILIOGRAPHY 53 ANNEX 59 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1: The Ballard Mazer (photograph courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, reproduced with the permission of the Warden and Fellows of All Souls College). Figure 2: Thomas Ballard’s seal matrix (photograph courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, reproduced with their permission). Figure 3: Sketch-plan of the City of London showing sites associated with Thomas Walsingham. Figure 4: St Katherine’s Church in 1810 (reproduced from J.B. Nichols, Account of the Royal Hospital and Collegiate Church of St Katharine near the Tower of London (London, 1824)). Figure 5: Sketch-map of Kent showing sites associated with Thomas Walsingham. Figure 6: Aerial view of Scadbury Park (photograph, Alan Hart). Figure 7: Oyster shells excavated at Scadbury Manor (photograph, Janet Clayton). Figure 8: Surrey white-ware decorated jug excavated at Scadbury (photograph: Alan Hart). Figure 9: Lead token excavated from the moat-wall trench (photograph, Alan Hart). 2 THOMAS WALSINGHAM _______________________________________________________________________________ ABBREVIATIONS Arch Cant Archaeologia Cantiana Bradley H. Bradley, The Views of the Hosts of Alien Merchants 1440-1444 (London, 2011) CCR Calendar of Close Rolls CFR Calendar of Fine Rolls CLB (A-L) R.R. Sharpe (ed.), Calendar of Letter-books preserved among the archives of the Corporation of the City of London at the Guildhall (London, 1899-1912) CPR Calendar of Patent Rolls Hasted E.