Caesar Farah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840-1914 the Divisive Legacy of Sectarianism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2008-12 Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840-1914 the divisive legacy of Sectarianism Francioch, Gregory A. Monterey, California. Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/3850 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS NATIONALISM IN OTTOMAN GREATER SYRIA 1840- 1914: THE DIVISIVE LEGACY OF SECTARIANISM by Gregory A. Francioch December 2008 Thesis Advisor: Anne Marie Baylouny Second Reader: Boris Keyser Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202-4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704-0188) Washington DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2008 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE Nationalism in Ottoman Greater Syria 1840- 5. FUNDING NUMBERS 1914: The Divisive Legacy of Sectarianism 6. AUTHOR(S) Greg Francioch 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. -

Arabic Manual. a Colloquial Handbook in the Syrian

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES IN MEMORY OF Gerald E. Baggett CO .Sk ? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2008 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/arabicmanualcollOOcrow LUZAC'S ORIENTAL GRAMMARS SERIES. LUZAC'S ORIENTAL GRAMMARS SERIES. Vol. I. Manual of Hebrew Syntax. By J. D. WlJNKOOP and C. VAN DEN BlESEN. 2S. 6d. „ II. Manual of Hebrew Grammar. By J. D. WlJNKOOP and C. VAN DEN BlESEN. 2s. 6d. „ III. A Modern Persian Colloquial Grammar, with Dialogues, Extracts from Nasir Eddin Shah's Diaries, Tales, etc., and Vocabulary. By F. Rosen. \os. 6d. „ IV. Arabic Manual. By F. E. Crow. ARABIC MANUAL : ARABIC MANUAL A COLLOQUIAL HANDBOOK IN THE SYRIAN DIALECT FOR THE USE OF VISITORS TO SYRIA AND PALESTINE, CONTAINING A SIMPLIFIED GRAMMAR, A COMPREHENSIVE ENGLISH AND ARABIC VOCABULARY AND DIALOGUES. THE WHOLE IN ENGLISH CHARACTERS, CAREFULLY TRANSLITERATED, THE PRONUNCIATION BEING FULLY INDICATED. F. E. CROW, I.ATE II. P.. M. VICE-CONSUL AT I'.EIUUT. LONDON L UZAC & Co., PUBLISHERS TO THE INDIA OFFICE 46, Great Russell Street 1901. PRINTED BY E. J. HRILI>, I.EYDEN (HOLLAND). c cor- PREF A CE. It is hoped that the present work will supply a want, which has long been felt by those, who, for purposes of business or recreation, have been led to visit Syria and Palestine. The extensive scope of English and American missionary development, and the yearly in- crease in the influx of tourists to this country may, perhaps, render both useful and acceptable any means, which facilitate the acquisition of colloquial Arabic. -

Cretaceous Transition in Mount Lebanon

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by I-Revues Carnets Geol. 16 (8) Some steps toward a new story for the Jurassic - Cretaceous transition in Mount Lebanon Bruno GRANIER 1 Christopher TOLAND 2 Raymond GÈZE 3 Dany AZAR 3, 4 Sibelle MAKSOUD 3 Abstract: The stratigraphic framework of the Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous strata of Lebanon that dates back to DUBERTRET's publications required either consolidation or full revision. The preliminary results of our investigations in the Mount Lebanon region are presented here. We provide new micro- paleontological and sedimentological information on the Salima Oolitic Limestones, which is probably an unconformity-bounded unit (possibly Early Valanginian in age), and the "Grès du Liban" (Barremian in age). Our revised bio- and holostratigraphic interpretations and the new age assignations lead us to em- phasize the importance of the two hiatuses in the sedimentary record below and above the Salima, i.e., at the transition from the Jurassic to the Cretaceous. Key Words: Tithonian; Valanginian; Barremian; hiatus; unconformity; Salima Oolitic Limestones; "Grès du Liban"; amber; Balkhania. Citation: GRANIER B., TOLAND C., GÈZE R., AZAR D. & MAKSOUD S. (2016).- Some steps toward a new story for the Jurassic - Cretaceous transition in Mount Lebanon.- Carnets Geol., Madrid, vol. 16, no. 8, p. 247- 269. Résumé : Avancées dans une réécriture de l'histoire de la transition du Jurassique au Crétacé dans le Mont Liban.- Le canevas stratigraphique du Jurassique supérieur et du Crétacé inférieur du Liban date des publications anciennes de DUBERTRET et aurait donc besoin d'être soit toiletté et consolidé, soit révisé de fond en comble. -

AUB Employee Discount Program

Because we appreciate you 100%! AUB faculty and staff will have access to valuable discounts from a wide variety of vendors and businesses! The Employee Discount Program is brought to you by the Human Resources Departments, Campus and Medical Center, to show appreciation to all faculty and staff for their hard work and dedication. Just show your AUB ID and get the best value on goods and services from the below vendors*. This list will be updated regularly with more vendors and more discounted offers. *AUB is not endorsing any of the vendors listed below or guaranteeing the quality of any of their products or services received. ABED TAHAN . Up to 30% discounts . Pre‐campaigns benefits prior to Events (Bazaar, Black Friday, and other promotional events) . 24/7 customer service support 01‐645645 Excluded from the above offers: . Mobiles, Tablets, Wearable, Gaming consoles . Special Offers / Clearance items . Bazaar, Black Friday and other promotional activities All discounts apply on the selling price. AGHASARKISSIAN Discounted rate as per the below: . 30% (Thirty) on Veneta Cucine (Italian Kitchen manufacturer) www.venetacucine.com . 20% (Twenty) on AEG, Panasonic, Tognana, Thomson and Indigo . 10% (Ten) on all remaining brands Excluded from the above: . Multimedia and IT Product (Laptop, Mobile, LED, etc.) The discount is based on retail price. ALLIANZ SNA 15% discount on individual travel insurance policies. Contact details: Allianz SNA s.a.l. Hazmieh Phone 05‐956600 or 05‐422240 Fax 961 5 956624 Ms. Jenny Nasr [email protected] ANTOINE 10% discount on all products at: . Antoine Achrafieh . Antoine Sin el Fil . -

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918)

The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) by Melanie Tanielian A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Beshara Doumani Professor Saba Mahmood Professor Margaret L. Anderson Professor Keith D. Watenpaugh Fall 2012 The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) © Copyright 2012, Melanie Tanielian All Rights Reserved Abstract The War of Famine: Everyday Life in Wartime Beirut and Mount Lebanon (1914-1918) By Melanie Tanielian History University of California, Berkeley Professor Beshara Doumani, Chair World War I, no doubt, was a pivotal event in the history of the Middle East, as it marked the transition from empires to nation states. Taking Beirut and Mount Lebanon as a case study, the dissertation focuses on the experience of Ottoman civilians on the homefront and exposes the paradoxes of the Great War, in its totalizing and transformative nature. Focusing on the causes and symptoms of what locals have coined the ‘war of famine’ as well as on international and local relief efforts, the dissertation demonstrates how wartime privations fragmented the citizenry, turning neighbor against neighbor and brother against brother, and at the same time enabled social and administrative changes that resulted in the consolidation and strengthening of bureaucratic hierarchies and patron-client relationships. This dissertation is a detailed analysis of socio-economic challenges that the war posed for Ottoman subjects, focusing primarily on the distorting effects of food shortages, disease, wartime requisitioning, confiscations and conscriptions on everyday life as well as on the efforts of the local municipality and civil society organizations to provision and care for civilians. -

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Wednesday, December 09, 2020 Report #266 Time Published: 07:00 PM

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Wednesday, December 09, 2020 Report #266 Time Published: 07:00 PM Occupancy rate of COVID-19 Beds and Availability For daily information on all the details of the beds distribution availablity for Covid-19 patients among all governorates and according to hospitals, kindly check the dashboard link: Computer : https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-PC Phone:https:/bit.ly/DRM-HospitalsOccupancy-Mobile All reports and related decisions can be found at: http://drm.pvm.gov.lb Or social media @DRM_Lebanon Distribution of Cases by Villages Beirut 81 Baabda 169 Maten 141 Chouf 66 Kesrwen 78 Tripoli 35 Ain Mraisseh 1 Chiyah 14 Borj Hammoud 5 Damour 1 Jounieh Kaslik 1 Trablous Ez Zeitoun 3 Raoucheh 2 Jnah 8 Nabaa 1 Naameh 2 Zouk Mkayel 1 Trablous Et Tall 3 Hamra 6 Ouzaai 1 Sinn Fil 1 Haret En Naameh 1 Nahr El Kalb 1 Trablous El Qoubbeh 7 Msaitbeh 3 Bir Hassan 1 Horch Tabet 1 Chhim 3 Haret El Mir 2 Trablous Ez Zahriyeh 2 Ouata Msaitbeh 1 Ghbayreh 13 Jisr Bacha 1 Daraiya 3 Jounieh Ghadir 4 Trablous Jardins 1 Mar Elias 3 Ain Roummaneh 15 Jdaidet Matn 3 Ketermaya 15 Zouk Mosbeh 7 Mina N:1 1 Sanayeh 1 Furn Chebbak 6 Baouchriyeh 4 Aanout 1 Adonis 7 Qalamoun 1 Zarif 1 Haret Hreik 42 Daoura 2 Sibline 1 Jounieh Haret Sakhr 5 Beddaoui 1 Mazraa 1 Laylakeh 2 Raouda Baouchriyeh 2 Barja 9 Kfar Yassine 1 Ouadi En Nahleh 1 Borj Abou Haidar 3 Borj Brajneh 11 Sadd Baouchriyeh 3 Jiyeh 2 Tabarja 1 Camp Beddaoui 1 Basta Faouqa 1 Mreijeh 2 Sabtiyeh 5 Jadra 1 Adma Oua Dafneh 8 Others 14 Tariq Jdideh 5 Baabda 4 Deir -

Mt Lebanon & the Chouf Mountains ﺟﺒﻞ ﻟﺒﻨﺎن وﺟﺒﺎل اﻟﺸﻮف

© Lonely Planet 293 Mt Lebanon & the Chouf Mountains ﺟﺒﻞ ﻟﺒﻨﺎن وﺟﺒﺎل اﻟﺸﻮف Mt Lebanon, the traditional stronghold of the Maronites, is the heartland of modern Leba- non, comprising several distinct areas that together stretch out to form a rough oval around Beirut, each home to a host of treasures easily accessible on day trips from the capital. Directly to the east of Beirut, rising up into the mountains, are the Metn and Kesrouane districts. The Metn, closest to Beirut, is home to the relaxed, leafy summer-retreats of Brum- mana and Beit Mery, the latter host to a fabulous world-class winter festival. Further out, mountainous Kesrouane is a lunar landscape in summer and a skier’s paradise, with four resorts to choose from, during the snowy winter months. North from Beirut, the built-up coastal strip hides treasures sandwiched between concrete eyesores, from Jounieh’s dubiously hedonistic ‘super’ nightclubs and gambling pleasures to the beautiful ancient port town of Byblos, from which the modern alphabet is believed to have derived. Inland you’ll find the wild and rugged Adonis Valley and Jebel Tannourine, where the remote Afqa Grotto and Laklouk, yet another of Lebanon’s ski resorts, beckon travellers. To the south, the lush green Chouf Mountains, where springs and streams irrigate the region’s plentiful crops of olives, apples and grapes, are the traditional home of Lebanon’s Druze population. The mountains hold a cluster of delights, including one real and one not-so-real palace – Beiteddine and Moussa respectively – as well as the expansive Chouf THE CHOUF MOUNTAINS Cedar Reserve and Deir al-Qamar, one of the prettiest small towns in Lebanon. -

Updated Master Plan for the Closure and Rehabilitation

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY OF LEBANON Volume A JUNE 2017 Copyright © 2017 All rights reserved for United Nations Development Programme and the Ministry of Environment UNDP is the UN's global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life. We are on the ground in nearly 170 countries, working with them on their own solutions to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, they draw on the people of UNDP and our wide range of partners. Disclaimer The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of its authors, and do not necessarily reect the opinion of the Ministry of Environment or the United Nations Development Programme, who will not accept any liability derived from its use. This study can be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Please give credit where it is due. UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES THROUGHOUT THE COUNTRY OF LEBANON Volume A JUNE 2017 Consultant (This page has been intentionally left blank) UPDATED MASTER PLAN FOR THE CLOSURE AND REHABILITATION OF UNCONTROLLED DUMPSITES MOE-UNDP UPDATED MASTER PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ....................................................................................................................................... v List of Tables .............................................................................................................................................. -

Mount Lebanon 1 Electoral District: Keserwan and Jbeil

The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 1 Electoral Report District: Keserwan and Jbeil Georgia Dagher FEB 2021 Jbeil Keserwan Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Mount Lebanon 1 Electoral District: Keserwan and Jbeil Georgia Dagher Georgia Dagher is a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. Her research focuses on parliamentary representation, namely electoral behavior and electoral reform. She has also previously contributed to LCPS's work on international donors conferences and reform programs. She holds a degree in Politics and Quantitative Methods from the University of Edinburgh. The author would like to thank Sami Atallah, Daniel Garrote Sanchez, Ben Rejali, and Micheline Tobia for their contribution to this report 2 LCPS Report Executive Summary In the Lebanese parliamentary elections of 2018, the electoral district of Mount Lebanon 1—which combined Keserwan and Jbeil—saw a competitive race, with candidates from three electoral lists making it to parliament. -

Syria Refugee Response ±

S Y R I A R E F U G E E R E S P O N S E LEBANON Beirut and Mount Lebanon Governorates Distribution of the Registered Syrian Refugees at the Cadastral Level As of 31 January 2016 Fghal Distribution of the Registered Syrian Kfar Kidde Berbara Jbayl Chmout 24 Maad Refugees by Province 20 Bekhaaz Aain Kfaa Mayfouq Bejje 9 Mounsef Gharzouz 27 Qottara Jbayl BEIRUT 7 2 Kharbet Jbayl 16 Tartij Chikhane GhalbounChamate 29 9 Rihanet Jbayl 17 Total No. of Household Registered Hsarat Haqel Lehfed 8,680 12 Hasrayel Aabaydat Beit Habbaq 22 Jeoddayel Jbayl 77 Hbaline 33 Jaj 38 Kfoun Saqiet El-Khayt Ghofrine 31 kafr Total No. of Individuals Registered 28,523 24 11 Behdaydat 6 Habil Saqi Richmaya Aarab El-Lahib Kfar Mashoun 19 Aamchit 27 Birket Hjoula Hema Er-Rehban 962 Bintaael Michmich Jbayl Edde Jbayl 33 63 7 Hema Mar Maroun AannayaLaqlouq MOUNT LEBANON Bichtlida Hboub Ehmej 19 8 Hjoula 57 69 Jbayl 3 Total No. of Household Registered 1,764 Bmehrayn Brayj Jbayl 74,267 Ras Osta Jbeil Aaqoura 10 Kfar Baal Mazraat El-Maaden Mazraat Es Siyad Qartaboun Jlisse 53 43 Blat Jbeil 140 9 19 Sebrine Aalmat Ech-Chamliye Total No. of Individuals Registered 531 Tourzaiya Mghayre Jbeil 283,433 Mastita 24 Tadmor Bchille Jbayl Jouret El-Qattine 8 16 190 47 1 Ferhet Aalmat Ej-Jnoubiye Yanouh Jbayl Zibdine Jbayl Bayzoun 5 Hsoun Souanet Jbayl Qartaba Mar Sarkis 17 33 4 2 3 Boulhos Hdeine Halate Aalita 272 Fatre Frat 933 1 Aain Jrain Aain El-GhouaybeSeraaiita Majdel El-Aqoura Adonis Jbayl Mchane Bizhel 7 Janne 8 Ghabat Aarasta 112 42 6 18 Qorqraiya 11 Kharayeb Nahr Ibrahim -

Syria Refugee Response ±

S Y R I A R E F U G E E R E S P O N S E LEBANON Beirut and Mount Lebanon Governorates Distribution of the Registered Syrian Refugees at the Cadastral Level As of 31 March 2014 Fghal N N " 3 " 0 0 ' Distribution of the Registered Syrian ' 2 Kfar Kidde 2 1 1 ° ° 4 Chmout 4 3 Berbara Jbayl 3 Refugees by Province Maad Bekhaaz Aain Kfaa Mayfouq Bejje Mounsef Qottara Jbayl BEIRUT Gharzouz Kharbet Jbayl Tartij 7 Ghalboun 15 Chikhane 5 Hsarat Total No. of Household Registered Rihanet Jbayl Chamate Haqel Lehfed 7,453 Hasrayel 2 Aabaydat Jeoddayel Jbayl 1 38 Beit Habbaq 22 Jaj 19 Hbaline Ghofrine 8 Kfoun Total No. of Individuals Registered 26,879 14 kafr Habil Saqi Richmaya Aarab El-Lahib Kfar Mashoun Behdaydat Aamchit 11 11 Birket Hjoula Hema Er-Rehban 379 Bintaael Michmich Jbayl Edde Jbayl 3 10 2 MOUNT LEBANON Hema Mar Maroun Aannaya Laqlouq Hboub Ehmej 11 Bichtlida Hjoula 21 37 Jbayl 11 Total No. of Household Registered 782 Bmehrayn Kfar Qouas 53,731 Ras Osta Jbeil Aaqoura Brayj Jbayl Kfar Baal Mazraat El-Maaden Mazraat Es Siyad Qartaboun Jlisse 21 45 Blat Jbeil 82 10 23 Sebrine Tourzaiya Aalmat Ech-Chamliye Total No. of Individuals Registered 292 Mghayre Jbeil 219,406 Mastita 3 15 Bchille Jbayl Jouret El-Qattine Tadmor 7 110 19 Ferhet Aalmat Ej-Jnoubiye Yanouh Jbayl Zibdine Jbayl Bayzoun Souanet Jbayl Mar Sarkis 11 Hsoun Qartaba 17 10 2 Boulhos Hdeine Halate Aalita 133 Fatre Frat 332 10 Aain El-Ghouaybe Seraaiita Majdel El-Aqoura Adonis Jbayl Mchane Aain Jrain Aarasta Bizhel 7 Ghabat 74 8 Janne 4 5 Qorqraiya 5 Kharayeb Nahr Ibrahim Mradiye -

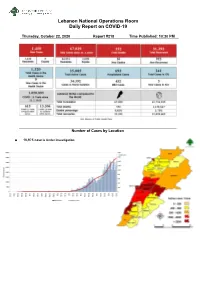

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19

Lebanon National Operations Room Daily Report on COVID-19 Thursday, October 22, 2020 Report #218 Time Published: 10:30 PM Number of Cases by Location • 10,975 case is Under investigation Beirut 60 Chouf 43 Kesrwen 98 Matn 151 Ashrafieh 9 Anout 1 Ashkout 1 Ein Alaq 1 Ein Al Mreisseh 1 Barja 6 Ajaltoun 2 Ein Aar 1 Basta Al Fawka 1 Barouk 1 Oqaybeh 1 Antelias 3 Borj Abi Haidar 2 Baqaata 1 Aramoun 1 Baabdat 3 Hamra 1 Chhim 6 Adra & Ether 1 Bouchrieh 1 Mar Elias 3 Damour 1 Adma 1 Beit Shabab 2 Mazraa 3 Jiyyeh 2 Adonis 3 Beit Mery 1 Mseitbeh 2 Ketermaya 2 Aintoura 1 Bekfaya 2 Raouche 1 Naameh 5 Ballouneh 3 Borj Hammoud 9 Ras Beirut 1 Niha 3 Fatqa 1 Bqennaya 1 Sanayeh 2 Wady Al Zayne 1 Bouar 2 Broummana 2 Tallet El Drouz 1 Werdanieh 1 Ghazir 3 Bsalim 1 Tallet Al Khayat 1 Rmeileh 1 Ghbaleh 1 Bteghrine 1 Tariq Jdeedeh 4 Saadiyat 1 Ghodras 2 Byaqout 1 Zarif 1 Sibline 1 Ghosta 3 Dbayyeh 3 Others 27 Zaarourieh 1 Hrajel 1 Dekwene 12 Baabda 101 Others 9 Ghadir 2 Dhour Shweir 1 Ein El Rimmaneh 8 Hasbaya 6 Haret Sakher 6 Deek Al Mahdy 2 Baabda 4 Hasbaya 1 Kaslik 3 Fanar 4 Bir Hassan 1 Others 5 Sahel Alma 7 Horch Tabet 1 Borj Al Brajneh 17 Byblos 25 Sarba 5 Jal El Dib 3 Botchay 1 Blat 1 Kfardebian 1 Jdeidet El Metn 2 Chiah 6 Halat 1 Kfarhbab 1 Mansourieh 2 Forn Al Shebbak 3 Jeddayel 1 Kfour 3 Aoukar 3 Ghobeiry 3 Monsef 1 Qlei'aat 1 Mazraet Yashouh 3 Hadat 12 Ras Osta 1 Raasheen 2 Monteverde 2 Haret Hreik 5 Others 20 Safra 2 Mteileb 3 Hazmieh 4 Jezzine 12 Sehaileh 1 Nabay 1 Loueizy 1 Baysour 1 Tabarja 6 Naqqash 3 Jnah 2 Ein Majdoleen 1 Zouk Michael 1 Qanbt