Upper Grand Coulee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Gills Coulee Creek, 2006 [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1190/gills-coulee-creek-2006-pdf-11190.webp)

Gills Coulee Creek, 2006 [PDF]

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Bureau of Watershed Management Sediment TMDL for Gills Coulee Creek INTRODUCTION Gills Coulee Creek is a tributary stream to the La Crosse River, located in La Crosse County in west central Wisconsin. (Figure A-1) The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) placed the entire length of Gills Coulee Creek on the state’s 303(d) impaired waters list as low priority due to degraded habitat caused by excessive sedimentation. The Clean Water Act and US EPA regulations require that each state develop Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) for waters on the Section 303(d) list. The purpose of this TMDL is to identify load allocations and management actions that will help restore the biological integrity of the stream. Waterbody TMDL Impaired Existing Codified Pollutant Impairment Priority WBIC Name ID Stream Miles Use Use Gills Coulee 0-1 Cold II Degraded 1652300 168 WWFF Sediment High Creek 1-5 Cold III Habitat Table 1. Gills Coulee use designations, pollutants, and impairments PROBLEM STATEMENT Due to excessive sedimentation, Gills Coulee Creek is currently not meeting applicable narrative water quality criterion as defined in NR 102.04 (1); Wisconsin Administrative Code: “To preserve and enhance the quality of waters, standards are established to govern water management decisions. Practices attributable to municipal, industrial, commercial, domestic, agricultural, land development, or other activities shall be controlled so that all waters including mixing zone and effluent channels meet the following conditions at all times and under all flow conditions: (a) Substances that will cause objectionable deposits on the shore or in the bed of a body of water, shall not be present in such amounts as to interfere with public rights in waters of the state. -

Northrup Canyon

Northrup Canyon Why? Fine basalt, eagles in season Season: March to November; eagles, December through February Ease: Moderate. It’s about 1 ¾ miles to an old homestead, 3 ½ miles to Northrup Lake. Northrup Canyon is just across the road from Steamboat Rock, and the two together make for a great early or late season weekend. Northrup, however, is much less visited, so offers the solitude that Steamboat cannot. In season, it’s also a good spot for eagle viewing, for the head of the canyon is prime winter habitat for those birds. The trail starts as an old road, staying that way for almost 2 miles as it follows the creek up to an old homestead site. At that point the trail becomes more trail-like as it heads to the left around the old chicken house and continues the last 1 ½ miles to Northrup Lake. At its start, the trail passes what I’d term modern middens – piles of rusted out cans and other metal objects left from the time when Grand Coulee Dam was built. Shortly thereafter is one of my two favorite spots in the hike – a mile or more spent walking alongside basalt cliffs decorated, in places, with orange and yellow lichen. If you’re like me, about the time you quit gawking at them you realize that some of the columns in the basalt don’t look very upright and that, even worse, some have already fallen down and, even more worse, some have not quite finished falling and are just above the part of the trail you’re about to walk. -

Section 1135 Ecosystem Restoration Study

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Omaha District Section 1135 Ecosystem Restoration Study Integrated Feasibility Report and Environmental Assessment Southern Platte Valley Denver, Colorado June 2018 South Platte River near Overland Pond Park TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 1.1. STUDY AUTHORITY ............................................................................................ 1 1.2. STUDY SPONSOR AND CONGRESSIONAL AUTHORIZATION ................... 1 1.3. STUDY AREA AND SCOPE ................................................................................. 1 2. PURPOSE, NEED AND SIGNIFICANCE .................................................................... 3 2.1. NEED: PROBLEMS AND OPPORTUNITIES ...................................................... 4 2.2. PURPOSE: OBJECTIVES AND CONSTRAINTS ................................................ 7 2.3. SIGNIFICANCE ...................................................................................................... 8 3. CURRENT AND FUTURE CONDITIONS ................................................................ 16 3.1. PLANNING HORIZON ........................................................................................ 16 3.2. EXISTING CONDITIONS .................................................................................... 16 3.3. PREVIOUS STUDIES .......................................................................................... 17 3.4. EXISTING PROJECTS -

Jefferson County, Colorado, and Incorporated Areas

VOLUME 1 OF 8 JEFFERSON COUNTY, Jefferson County COLORADO AND INCORPORATED AREAS Community Community Name Number ARVADA , CITY OF 085072 BOW MAR, TOWN OF * 080232 EDGEWATER, CITY OF 080089 GOLDEN, CITY OF 080090 JEFFERSON COUNTY 080087 (UNINCORPORATED AREAS) LAKESIDE , TOWN OF * 080311 LAKEWOOD, CITY OF 085075 MORRISON, TOWN OF 080092 MOUNTAIN VIEW, TOWN OF* 080254 WESTMINSTER, CITY OF 080008 WHEAT RIDGE , CITY OF 085079 *NO SPECIAL FLOOD HAZARD AREAS IDENTIFIED REVISED DECEMBER 20, 2019 Federal Emergency Management Agency FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY NUMBER 08059CV001D NOTICE TO FLOOD INSURANCE STUDY USERS Communities participating in the National Flood Insurance Program have established repositories of flood hazard data for floodplain management and flood insurance purposes. This Flood Insurance Study may not contain all data available within the repository. It is advisable to contact the community repository for any additional data. Part or all of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised and republished at any time. In addition, part of this Flood Insurance Study may be revised by the Letter of Map Revision process, which does not involve republication or redistribution of the Flood Insurance Study. It is, therefore, the responsibility of the user to consult with community officials and to check the community repository to obtain the most current Flood Insurance Study components. Initial Countywide FIS Effective Date: June 17, 2003 Revised FIS Dates: February 5, 2014 January 20, 2016 December 20, 2019 i TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME 1 – December -

Washington Geology

JULY 1978 VOLUME 6 - NUMBER 3 A PLBLICATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES WASHINGTON GEOWGIC NEWSLETTER BERT L.COLE COMMISSIONER OF PUBLIC LANDS RALPH A BESWICK, Supervisor VAUGHN E. LIVINGSTON,JR.,State Geologist DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES DEPARTMENT Of NATURAL RESOURCES, DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES, OLYMPIA, WASHINGTON, 98504 LOCATION MAP : DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES DEPT. SOCIAL AND HEALTH SERVICES t ~ i~L f ...J ~ i ,...... N g a: ~ ~OGY ANO EARTH <t tt RESOURCES D u -, t STATE CAPITOL ... TACOMA S~TILE- IDEPT. HIGHWAYS CITY CENTER FREEWAY EXIT PORTLA~ STATE CAPITOL EXIT Vaughn E. (Ted) Livingston, Jr., Supervisor Geologic Staff J. Eric Schuster, Assistant Supervisor Minerals and Energy Geologists Land Use Geologists Carl McFarland James G. Rigby Allen J. Fiksdal Keith L. Stoffel Clint Milne Glennda B. Tucker Kurt L. 0th berg Gerald W. Thorsen Wayne S. Moen Ellis R. Vonheeder Pamela Palmer Weldon W. Rau Charles W. Walker Regulations and Operations Surface Mined Land Reclamation and Oil and Gos Conservation Act Donald M. Ford, Assistant Supervisor Publications: Library: Laboratory: Secretaries: Loura Broy Connie Manson Arnold W. Bowman Patricia Ames Keith Ikerd Cherie Dunwoody Wonda Walker Kim Summers Pamela Whitlock Mailing address: Deportment of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resou rces Olympia, WA 98504 (206) 753-6183 ORIGIN OF THE GRAND COULEE AND DRY FALLS by Ted Livingston Washington State hos many interesting geo original terrain until in the Grand Coulee area it was logic features. Among the more outstanding dre the completely buried. During the course of these erup Grand Coulee and Dry Falls . -

Rainfall Thresholds for Flow Generation in Desert Ephemeral

Water Resources Research RESEARCH ARTICLE Rainfall Thresholds for Flow Generation 10.1029/2018WR023714 in Desert Ephemeral Streams 1 1 2 1 Key Points: Stephanie K. Kampf G!), Joshua Faulconer , Jeremy R. Shaw G!), Michael Lefsky , Rainfall thresholds predict 3 2 streamflow responses with high Joseph W. Wagenbrenner G!), and David J. Cooper G!) accuracy in small hyperarid and 1 2 semiarid watersheds Department of Ecosystem Science and Sustainability, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, USA, Department 3 Using insufficient rain data usually of Forest and Rangeland Stewardship, Colorado State University, FortCollins, Colorado, USA, USDA Forest Service, Pacific increases threshold values for larger Southwest Research Station, Arcata, California,USA watersheds, leading to apparent scale dependence in thresholds Declines in flow frequency and Rainfall thresholds for streamflow generation are commonly mentioned in the literature, but increases in thresholds with drainage Abstract area are steeper in hyperarid than in studies rarely include methods for quantifying and comparing thresholds. This paper quantifies thresholds semiarid watersheds in ephemeral streams and evaluates how they are affected by rainfall and watershed properties. The study sites are in southern Arizona, USA; one is hyperarid and the other is semiarid. At both sites rainfall and 3 2 2 Supporting Information: streamflow were monitored in watersheds ranging from 10- to 10 km . Streams flowed an average of 0-5 • Supporting Information 51 times per year in hyperarid watersheds and 3-11 times per year in semiarid watersheds. Although hyperarid sites had fewer flow events, their flow frequency (fraction of rain events causing flow) was higher than in Correspondence to: 2 semiarid sites for small ( < 1 km ) watersheds. -

Stormwater Ordinance Leaf & Grass Blowing Into Storm Drains Lafayette

Good & Bad • Stormwater GOOD: Only Rain in the Drain! The water drains to Ordinance the river. Leaf & Grass Blowing into Storm Drains Lafayette BAD: Grass and leaves blown into a storm drain interfere with drainage. Parish Dirt is also being allowed in our waterways. Potential Illicit Discharge Sources: Environmental Quality • Sanitary sewer wastewater. Regulatory Compliance 1515 E. University Ave. • Effluent from septic tanks. Lafayette, LA 70501 Phone: 337-291-8529 • Laundry wastewater. Fax: 337-291-5620 • Improper disposal of auto and household toxics. www.lafayettela.gov/stormwater • Industrial byproduct discharge. Illicit Discharge (including leaf blowing) Stormwater Ordinance Stormwater Runoff Illicit Discharge Please be advised that the Environmental Grass clippings and leaves blown or swept is defined by the EPA as: Quality Division of Lafayette Consolidated into storm drains or into the street harms Any discharge into a municipal separate Government has recently adopted an waterways and our river. Storm drains flow storm sewer that is not composed entirely of into coulees and into the Vermilion River. rainwater and is not authorized by permit. Illicit Discharge (including leaf blowing) Grass clippings in the river rob valuable Stormwater Ordinance oxygen from our Vermilion River. Chapter 34. ENVIRONMENT When leaf and grass clippings enter the Signs of Potential Illicit Discharge Article 5. STORMWATER storm drain, flooding can occur. Only rain must enter the storm drain. When anything • Heavy flow during dry weather. Division 4 Sec. 34-452 but rain goes down the storm drain, it can • Strong odor. It is now in effect and being enforced. You become a drainage problem. may access this ordinance online at Grass clippings left on the ground improve the • Colorful or discolored liquid. -

Top 26 Trails in Grant County 2020

and 12 Watchable Wildlife Units For more information, please contact: Grant County Tourism Commission P.O. Box 37, Ephrata, WA 98823 509.765.7888 • 800.992.6234 In Grant County, Washington TourGrantCounty.com TOP TRAILS Grant County has some of the most scenic and pristine vistas, hiking trails and outdoor 26 recreational opportunities in Washington State. and 12 Watchable Wildlife Units Grant County is known for its varied landscapes on a high desert plateau with coulees, lakes, in Grant County Washington reservoirs, sand dunes, canals, rivers, creeks, and other waterways. These diverse ecosystems Grant County Tourism Commission For Additional copies please contact: support a remarkable variety of fish and PO Box 37 Jerry T. Gingrich wildlife species that contribute to the economic, Ephrata, Washington 98837 Grant County Tourism Commission recreational and cultural life of the County. www.tourgrantcounty.com Grant County Courthouse PO Box 37 Ephrata, WA 98837 No part of this book may be reproduced in (509) 754-2011, Ext. 2931 any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without permission in For more information on writing from the Grant County Tourism Grant County accommodations Commission. www.tourgrantcounty.com © 2019, Grant County Tourism Commission Second printing, 10m Trails copy and photographs Book, map and cover design by: provided by: Denise Adam Graphic Design Cameron Smith, Lisa Laughlin, J. Kemble, Veradale, WA 99037 Shawn Cardwell, Mark Amara, (509) 891-0873 Emry Dinman, Harley Price, [email protected] Sebastian Moraga and Madison White Printed by: Rewriting and editing by: Mark Amara Pressworks 2717 N. Perry Street Watchable Wildlife copy and Spokane, Washington 99207 photographs provided by: (509) 462-7627 Washington Department of [email protected] Fish and Wildlife Photograph by Lisa Laughlin CONTENTS CONTENTS Grant County Trails and Hiking Grant County Watchable Wildlife Viewing Upper Grand Coulee Area 1. -

Gully Migration on a Southwest Rangeland Watershed

Gully Migration on a Southwest Rangeland Watershed Item Type text; Article Authors Osborn, H. B.; Simanton, J. R. Citation Osborn, H. B., & Simanton, J. R. (1986). Gully migration on a Southwest rangeland watershed. Journal of Range Management, 39(6), 558-561. DOI 10.2307/3898771 Publisher Society for Range Management Journal Journal of Range Management Rights Copyright © Society for Range Management. Download date 25/09/2021 03:08:17 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/645347 Gully Migration on a Southwest Rangeland Watershed H.B. OSBORN AND J.R. SIMANTON Abstract Most rainfall and almost all runoff from Southwestern range- on gully erosion is from farmlands, rather than rangelands. lands are the result of intense summer thunderstorm null. Gully The southeastern Arizona geologic record indicates gullying has growth and headcutting are evident throughout the region. A occurred in the past, but the most recent intense episode of acceler- large, active headcut on a Walnut Gulch subwatershed has been ated gullying appears to have begun in the 1880’s (Hastings and surveyed at irregular intervals from 1966 to present. Runoff at the Turner 1965). Gullies in the 2 major stream channels of southeast- headcut was estimated using a kinematic cascade rainfall-runoff ern Arizona, the San Pedro and Santa Cruz Rivers, began because model (KINEROS). The headcut sediment contribution was about of man’s activities in the flood plains and were accelerated by 25% of the total sediment load measured downstream from the increased runoff from overgrazed tributary watersheds. -

Lesson 1 the Columbia River, a River of Power

Lesson 1 The Columbia River, a River of Power Overview RIVER OF POWER BIG IDEA: The Columbia River System was initially changed and engineered for human benefit Disciplinary Core Ideas in the 20th Century, but now balance is being sought between human needs and restoration of habitat. Science 4-ESS3-1 – Obtain and combine Lesson 1 introduces students to the River of Power information to describe that energy curriculum unit and the main ideas that they will investigate and fuels are derived from natural resources and their uses affect the during the eleven lessons that make up the unit. This lesson environment. (Clarification Statement: focuses students on the topics of the Columbia River, dams, Examples of renewable energy and stakeholders. Through an initial brain storming session resources could include wind energy, students record and share their current understanding of the water behind dams, and sunlight; main ideas of the unit. This serves as a pre-unit assessment nonrenewable energy resources are fossil fuels and fissile materials. of their understanding and an opportunity to identify student Examples of environmental effects misconceptions. Students are also introduced to the main could include loss of habitat to dams, ideas of the unit by viewing the DVD selection Rivers to loss of habitat from surface mining, Power. Their understanding of the Columbia River and the and air pollution from burning of fossil fuels.) stakeholders who depend on the river is deepened through the initial reading selection in the student book Voyage to the Social Studies Pacific. Economics 2.4.1 Understands how geography, natural resources, Students set up their science notebook, which they will climate, and available labor use to record ideas and observations throughout the unit. -

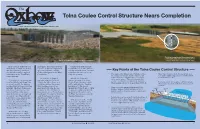

Tolna Coulee Control Structure Nears Completion

The Tolna Coulee Control Structure Nears Completion FROM THE NORTH DAKOTA STATE WATER COMMISSION The Tolna Coulee Control Strucutre on June 6. Inset shows water elevation measurement on The Tolna Coulee Control Structure prior to completion. structure at the same elvevation as the lakes. In the last part of May, the U.S. more likely. As a result, the Corps Construction of the structure Army Corps of Engineers (Corps), began the design and construction began in the fall of 2011, and was and their contractor, announced of a control structure on Tolna aided by the mild winter. Less than Key Points of the Tolna Coulee Control Structure they had substantially completed Coulee, with input from the Water a year later, the structure is now construction on the Tolna Coulee Commission. ready for operation. • The intent of the Tolna Control Structure is that • Once water begins to flow over the divide, stop control structure. the existing topography, not the structure, will logs in the middle of the structure will be placed The structure is designed Initially, the Corps will control discharge, with the removal of stop logs at an elevation of 1,457’. as the divide erodes. This will allow the lake Tolna Coulee is the natural outlet to permit erosion of the divide, manage operation of the Tolna to lower as it would have without the structure - from Devils Lake and Stump Lake. allowing the lake to lower, as it Coulee Control Structure, which while limiting releases to no more than 3,000 cfs. • If erosion occurs, the stop logs will be removed to As recently as 2011, the lake was would have without the project, will be guided by the “Standing the new lake elevation, with flows not to exceed less than four feet from overflowing while limiting releases to no Instructions To The Project 3,000 cfs. -

Dry Falls Visitor Center Due to the Fact That Many Travelers Saw These Unusual Landforms in the Landscape As They Drove the Coulee Corridor

Interactive Design Approach IMMERSIVE Theater Topo Model The design approach for the exhibits is closely integrated with the Seating architecture. The layering of massive, linear building walls pro- for 50-60 EXHIBIT vides a direction for the design and layout of exhibit components. Gallery Real ‘Today’ erratic OUTDOOR Terrace Building walls are cut open at strategic points to accommodate WITH EXhibits specific exhibits and to allow for circulation. Smaller, wall-panel exhibits are used for supports and dividers. Equipment ‘Volcanic ‘Ice Age Floods’ Room Period’ Approaching the center, visitors are forced to walk around a mas- sive erratic – these huge boulders are seemingly deposited directly Gallery Animal Modelled erratic Lava flow overhead Freestanding time line animal cutouts on the path to the front door. The displaced rock serves as a strong Welcome in floor icon of the violent events that occurred during the Ice Age Floods. Through the Visitor Center’s front doors, visitors are startled to see another massive erratic precariously wedged overhead between W M Retail / cafe the two parallel building walls. Just out of reach it makes an un- usual photo opportunity for visitors who puzzle over how the rock terrace stays in place. From an interpretive standpoint, it is important to Outdoor Classroom realize no actual erratics are present in the Sun Lakes-Dry Falls with Amphitheater State Park landscape. During the floods, water was moving too quickly for erratics to be deposited at Dry Falls - they were car- ried downstream and deposited in the Quincy and Pasco basins many miles away. However, the results of the visioning workshop determined that erratics are an important and exciting flood fea- ture to display at the Dry Falls Visitor Center due to the fact that many travelers saw these unusual landforms in the landscape as they drove the Coulee Corridor.