Themes of Exodus and Revolution in Ellison's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Movie List Please Dial 0 to Request

Movie List Please dial 0 to request. 200 10 Cloverfield Lane - PG13 38 Cold Pursuit - R 219 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi - R 46 Colette - R 202 5th Wave, The - PG13 75 Collateral Beauty - PG13 11 A Bad Mom’s Christmas - R 28 Commuter, The-PG13 62 A Christmas Story - PG 16 Concussion - PG13 48 A Dog’s Way Home - PG 83 Crazy Rich Asians - PG13 220 A Star is Born - R 20 Creed - PG13 32 A Walk Among the Tombstones - R 21 Creed 2 - PG13 4 Accountant, The - R 61 Criminal - R 19 Age of Adaline, The - PG13 17 Daddy’s Home - PG13 40 Aladdin - PG 33 Dark Tower, The - PG13 7 Alien:Covenant - R 67 Darkest Hour-PG13 2 All is Lost - PG13 52 Deadpool - R 9 Allied - R 53 Deadpool 2 - R (Uncut) 54 ALPHA - PG13 160 Death of a Nation - PG13 22 American Assassin - R 68 Den of Thieves-R (Unrated) 37 American Heist - R 34 Detroit - R 1 American Made - R 128 Disaster Artist, The - R 51 American Sniper - R 201 Do You Believe - PG13 76 Annihilation - R 94 Dr. Suess’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas - PG 5 Apollo 11 - G 233 Dracula Untold - PG13 23 Arctic - PG13 113 Drop, The - R 36 Assassin’s Creed - PG13 166 Dunkirk - PG13 39 Assignment, The - R 137 Edge of Seventeen, The - R 64 At First Light - NR 88 Elf - PG 110 Avengers:Infinity War - PG13 81 Everest - PG13 49 Batman Vs. Superman:Dawn of Justice - R 222 Everybody Wants Some!! - R 18 Before I Go To Sleep - R 101 Everything, Everything - PG13 59 Best of Me, The - PG13 55 Ex Machina - R 3 Big Short, The - R 26 Exodus Gods and Kings - PG13 50 Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk - R 232 Eye In the Sky - -

Exodus 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Exodus 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The Hebrew title of this book (we'elleh shemot) originated from the ancient practice of naming a Bible book after its first word or words. "Now these are the names of" is the translation of the first two Hebrew words. "The Hebrew title of the Book of Exodus, therefore, was to remind us that Exodus is the sequel to Genesis and that one of its purposes is to continue the history of God's people as well as elaborate further on the great themes so nobly introduced in Genesis."1 Exodus cannot stand alone, in the sense that the book would not make much sense without Genesis. The very first word of the book, translated "now," is a conjunction that means "and." The English title "Exodus" is a transliteration of the Greek word exodus, from the Septuagint translation, meaning "exit," "way out," or "departure." The Septuagint translators gave the book this title because of the major event in it, namely, the Israelites' departure from Egypt. "The exodus is the most significant historical and theological event of the Old Testament …"2 DATE AND WRITER Moses, who lived from about 1525 to 1405 B.C., wrote Exodus (17:14; 24:4; 34:4, 27-29). He could have written it, under the inspiration of the 1Ronald Youngblood, Exodus, pp. 9-10. 2Eugene H. Merrill, Kingdom of Priests, p. 57. Copyright Ó 2021 by Thomas L. Constable www.soniclight.com 2 Dr. Constable's Notes on Exodus 2021 Edition Holy Spirit, any time after the events recorded (after about 1444 B.C.). -

The Chapters of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy

Scholars Crossing An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible 5-2018 The Chapters of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/outline_chapters_bible Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "The Chapters of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy" (2018). An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible. 10. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/outline_chapters_bible/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Guide to the Systematic Study of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in An Alliterated Outline for the Chapters of the Bible by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy PART ONE: GOD'S DELIVERANCE OF ISRAEL-THE PREVIEW (EXODUS 1) The first part of the book of Exodus sets the scene for God's deliverance of his chosen people, Israel, from slavery in Egypt. SECTION OUTLINE ONE (EXODUS 1) Israel is being persecuted by an Egyptian pharaoh, probably Thutmose I. I. THE REASONS FOR PERSECUTION (Ex. 1:1-10) A. Fruitfulness (Ex. 1:1-7): Beginning with 70 individuals, the nation of Israel multiplies so quickly that they soon fill the land. B. Fear (Ex. 1:8-10): Such growth causes Pharaoh great concern, since the Israelites might join others and attack Egypt. II. -

Cullen Bunn Greg Land David Curiel Jay Leisten

MAGNETO PSYLOCKE SABRETOOTH M ARCHANGEL UNBEKNOWNST TO PSYLOCKE AND SABRETOOTH, MAGNETO HAS BROKERED AN ALLIANCE WITH THE HELLFIRE CLUB—FREQUENT ANTAGONISTS OF THE X-MEN. WHILE PSYLOCKE DOESN’T CONDONE THE PARTNERSHIP, MAGNETO PROVES IT HAS ITS ADVANTAGES WHEN THE HELLFIRE CLUB’S CONNECTIONS ARE ABLE TO PRODUCE INTEL ON THE ORGANIZATION THE X-MEN WERE INVESTIGATING, THE SOMEDAY CORPORATION. WHEN THE X-MEN LEARN THAT THE SOMEDAY CORPORATION, WHICH PROMISED TO PROTECT MUTANTS FROM THE TERRIGEN MISTS, IS INSTEAD WEAPONIZING THEM, THE X-MEN AND HELLFIRE CLUB INFILTRATE THEIR REMOTE BASE OF OPERATIONS AND TAKE A HOSTAGE. PSYLOCKE ENTERS THE UNCONSCIOUS MIND OF THIS ‘SLEEPER’ AND DISCOVERS THEIR NEXT MISSION: TO ATTACK AN ANTI-MUTANT RALLY AND INCITE GOVERNMENT ACTION. MEANWHILE, MYSTIQUE DISCOVERS THE CONTROLLING HAND BEHIND IT ALL: LONGTIME X-MEN FOE AND FORMER ACOLYTE OF MAGNETO, EXODUS. CULLEN GREG JAY DAVID BUNN LAND LEISTEN CURIEL WRITER PENCILER INKER COLOR ARTIST VC’s JOE CARAMAGNA GREG LAND & DAVID CURIEL LETTERER COVER ARTISTS CHRIS ROBINSON DANIEL KETCHUM MARK PANICCIA ASSISTANT EDITOR EDITOR X-MEN GROUP EDITOR AXEL ALONSO JOE QUESADA DAN BUCKLEY ALAN FINE EDITOR IN CHIEF CHIEF CREATIVE OFFICER PUBLISHER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER X-MEN CREATED BY STAN LEE & JACK KIRBY UNCANNY X-MEN No. 14, December 2016. Published Monthly except in January, March, June, and September by MARVEL WORLDWIDE, INC., a subsidiary of MARVEL ENTERTAINMENT, LLC. OFFICE OF PUBLICATION: 135 West 50th Street, New York, NY 10020. BULK MAIL POSTAGE PAID AT NEW YORK, NY AND AT ADDITIONAL MAILING OFFICES. © 2016 MARVEL No similarity between any of the names, characters, persons, and/or institutions in this magazine with those of any living or dead person or institution is intended, and any such similarity which may exist is purely coincidental. -

Marvel January – April 2021

MARVEL Aero Vol. 2 The Mystery of Madame Huang Zhou Liefen, Keng Summary THE MADAME OF MYSTERY AND MENACE! LEI LING finally faces MADAME HUANG! But who is Huang, and will her experience and power stop AERO in her tracks? And will Aero be able to crack the mystery of the crystal jade towers and creatures infiltrating Shanghai before they take over the city? COLLECTING: AERO (2019) 7-12 Marvel 9781302919450 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $17.99 USD/$22.99 CAD Paperback 136 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Captain America: Sam Wilson - The Complete Collection Vol. 2 Nick Spencer, Daniel Acuña, Angel Unzueta, Paul Re... Summary Sam Wilson takes flight as the soaring Sentinel of Liberty - Captain America! Handed the shield by Steve Rogers himself, the former Falcon is joined by new partner Nomad to tackle threats including the fearsome Scarecrow, Batroc and Baron Zemo's newly ascendant Hydra! But stepping into Steve's boots isn't easy -and Sam soon finds himself on the outs with both his old friend and S.H.I.E.L.D.! Plus, the Sons of the Serpent, Doctor Malus -and the all-new Falcon! And a team-up with Spider-Man and the Inhumans! The headline- making Sam Wilson is a Captain America for today! COLLECTING: CAPTAIN AMERICA (2012) 25, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA: FEAR HIM (2015) 1-4, ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA (2014) 1-6, AMAZING SPIDERMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, INHUMAN SPECIAL (2015) 1, Marvel ALL-NEW CAPTAIN AMERICA SPECIAL (2015) 1, CAPTAIN AMERICA: SAM WILSON (2015) 1-6 9781302922979 Pub Date: 1/5/21 On Sale Date: 1/5/21 $39.99 USD/$49.99 CAD Paperback 504 Pages Carton Qty: 40 Ages 13 And Up, Grades 8 to 17 Comics & Graphic Novels / Superheroes CGN004080 Marvel January to April 2021 - Page 1 MARVEL Guardians of the Galaxy by Donny Cates Donny Cates, Al Ewing, Tini Howard, Zac Thompson, .. -

Information on Candidates' Prohibition Record

X 3 J, t 0 l. S n 0 H ;..UJ'' 1 ~r1(:n1 No.Lsnc:r £ I: t - ~ v 7 c ~ • , .t 0 3 ':! 'a EA DS ATE Volume 25. No. 7 WESTERVILLE, OHIO, JULY, 1924 $1.00 Per Year MORE INFORMATION ON CANDIDATES' PROHIBITION RECORD In our write-up of candidate·s in the last issue of Home and State, we said that a prohibitionist and votes consistently for hibitionist, he supports all bills for its ef .. if any error had crept in we would gladly correct. ¥l e are glad to report very few all dry bills. We think he has an oppon fective enforcement. complaints. These were that we had not repeated rumors that they considered well ent, but do not know who he is. District 18 founded. They may be right. But we have further investigated these reports and can District 8 Marvin Jones, Amarillo, has been a not see our way clear to make any change whatever. Home and .State can not give Daniel E. Garrett, Houston, a life-long member of Congress for several terms-is currency to campaign rumors. In case of rumors, if any doubts arise, we prefer to prohibitionist, one of our leaders in the a life-long prohibitionist, and supports all give the candidate the benefit of the doubt. fight to make Texas dry, and votes con bills for effective enforcement. In this issue we give a lot more information on the campaign. We have at sistently for dry enforcement bills. Was tempted to use the same extreme care to be correct. -

Bible Translation As Missions Spring 2015 • Vol

SPRING 2015 • VOLUME 12, NUMBER 1 Bible Translation as Missions Spring 2015 • Vol. 12, No. 1 The Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Editor-in-Chief 2015 EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Charles S. Kelley, Th.D. Bart Barber, Ph.D. Executive Editor First Baptist Church of Farmersville, TX Steve W. Lemke, Ph.D. Rex Butler, Ph.D. Editor & BCTM Director New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary Adam Harwood, Ph.D. Research Assistant Nathan Finn, Ph.D. Patrick Cochran Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary Book Review Editors Eric Hankins, Ph.D. Archie England, Ph.D. First Baptist Church, Oxford, MS Dennis Phelps, Ph.D. Malcolm Yarnell, Ph.D. Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary The Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry is a research institute of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. The seminary is located at 3939 Gentilly Blvd., New Orleans, LA 70126. BCTM exists to provide theological and ministerial resources to enrich and energize ministry in Baptist churches. Our goal is to bring together professor and practitioner to produce and apply these resources to Baptist life, polity, and ministry. The mission of the BCTM is to develop, preserve, and communicate the distinctive theological identity of Baptists. The Journal for Baptist Theology and Ministry is published semiannually by the Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry. Copyright ©2015 The Baptist Center for Theology and Ministry, New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. All Rights Reserved. This peridiocal is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database® (ATLA RDB®), http://www.atla.com. CONTACT BCTM (800) 662-8701, ext. 8074 [email protected] www.baptistcenter.com SUBMISSIONS Visit the Baptist Center website for submission guidelines. -

Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish- American Experience Brian Klotz University of Rhode Island, [email protected]

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Senior Honors Projects Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island 2009 Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish- American Experience Brian Klotz University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Klotz, Brian, "Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish-American Experience" (2009). Senior Honors Projects. Paper 127. http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/127http://digitalcommons.uri.edu/srhonorsprog/127 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors Program at the University of Rhode Island at DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Honors Projects by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Klotz 1 Brian Klotz HPR401 Spring 2009 Secret Identities: Graphic Literature and the Jewish-American Experience In 1934, the comic book was born. Its father was one Maxwell Charles Gaines (né Ginsberg), a down-on-his-luck businessman whose previous career accomplishments included producing “painted neckties emblazoned with the anti-Prohibition proclamation ‘We Want Beer’” (Kaplan 2). Such things did not provide a sufficient income, and so a desperate Gaines moved himself and his family back in to his mother’s house in the Bronx. It was here, in a dusty attic, that Gaines came across some old newspaper comic strips and had his epiphany. Working with Eastern Color Printing, a “company that printed many of the Sunday newspaper comics sections in the Northeast” (Kaplan 2-3), Gaines began publishing pamphlet-sized collections of old comic strips to be sold to the public (this concept had been toyed with previously, but only as premiums or giveaways, not as an actual retail product). -

Book Review of Captain America

Book Review of Captain America and the Crusade Against Evil: The Dilemma of Zealous Nationalism, Robert Jewett and John Shelton Lawrence, G rand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003, 392 pp.; The Armageddon F actor: The Rise of Christian Nationalism in Canada, Marci McDonald, Random House Canada, 2010, 419 pp. These are disturbing books. One could feel having read them like a serious crime victim: the universe once seemed well ordered, predictably unfolding. Until violent crime strikes. And the equilibrium of the universe tilts. One thought perhaps Canada was a safe democracy. One thought the United States stood in reality for making the world safe for democracy. Both books urgently cry out, Think again! The Armageddon Factor is a second go at publishing on this theme, the first an essay in Walrus magazine in 2006. Captain America is reprised publication from initial discussion thirty years prior, and variously since. McDonald repeatedly alludes to, sometimes describes, antecedents from the States to the rise of Christian Nationalism. Jewett and Lawrence give a full-blown DFFRXQWRIZKDWWKH\FDOO³]HDORXVQDWLRQDOLVP´ from colonial times RQZDUGV,¶OOEHJLQZLWK their account. Captain America, a comic-ERRNFKDUDFWHU³FRPELQHVH[SORVLYHVWUHQJWKZLWKSHUIHFWmoral LQWXLWLRQV«KHWDNHVRQDPDVNHGLGHQWLW\DQGULGVWKHZRUOGRIHYLO>/LNH@$PHULFD¶VVHQVHRI mission ± and its affinity for violent crusading. This book explains the religious roots and historical development of this crusading tendency (p. xiii ´ Unpretentiously stated. The authors deliver masterfully. There are sixteen chapters in all. Meticulously researched and footnoted, the authors retain a steady gaze and commitment to neither under- nor overstatement. The first chapter discusses ³7KH&KDOOHQJHRID&RQWUDGLFWRU\&LYLO5HOLJLRQ´³2QHRIWKHSX]]OHVDERXWWKH$PHULFDQ civil religion is that biblical images of peacemaking through holy war reappear during times of FULVLV S ´WKH\DYHUThis is the founding national double-speak conundrum: peace through war is core American ethos from The War of Independence onwards. -

No.102$8.95 Deadpool and Cable TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc

Deadpool and Cable TM & © Marvel Characters, Inc. All Rights Reserved. No.102 February 2018 $8.95 1 82658 00116 2 INTERVIEW WITH DEADPOOL’S FIRST WRITER,FABIANNICIEZA FIRST INTERVIEW WITHDEADPOOL’S Punisher! Featuring Beatty, Claremont, Collins,Lash, Michelinie, anda Liefeldcover! Deathstroke •VigilanteTaskmaster •WildDogCable •andArchieMeets the ISSUE!MERCS &ANTI-HEROES ™ Volume 1, Number 102 February 2018 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Michael Eury PUBLISHER Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST Rob Liefeld COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek SPECIAL THANKS Terry Beatty Bob McLeod Jarrod Buttery David Michelinie Marc Buxton Fabian Nicieza Joe Casey Luigi Novi Ian Churchill Scott Nybakken Shaun Clancy Chuck Patton Max Allan Collins Philip Schweier FLASHBACK: Deathstroke the Terminator 2 Brian Cronin David Scroggy A bullet-riddled bio of the New Teen Titans breakout star Grand Comics Ken Siu-Chong Database Tod Smith BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: Taskmaster 17 Tom DeFalco Anthony Snyder Is he really the best at everything he does? Christos Gage Allen Stewart Mike Grell Steven Thompson FLASHBACK: The Vigilante 23 Gene Ha Fred Van Lente Who were those masked men in this New Teen Titans spinoff? Heritage Comics Marv Wolfman Auctions Doug Zawisza FLASHBACK: Wild Dog 36 Sean Howe Mike Zeck Max Allan Collins and Terry Beatty unmask DC’s ’80s vigilante Brian Ko Paul Kupperberg ROUGH STUFF 42 James Heath Lantz Grim-and-gritty graphite from Grell, Wrightson, Zeck, and Liefeld -

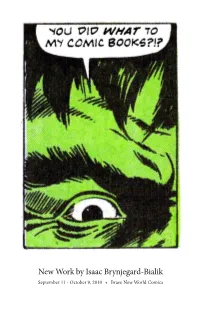

"You Did WHAT to My Comics?!?" Show Catalog

New Work by Isaac Brynjegard-Bialik September 11 - October 9, 2010 • Brave New World Comics Incredible Tree SOLD Fountains of the Deep SOLD 2010 2010 10" x 13" 18" x 24" The Incredible Tree [of Knowledge of “In the six hundredth year of Noah’s life, Good and Evil] is an exploration of the in the second month, on the seventeenth two-sided nature of knowledge. When day of the month, all the fountains of Adam and Eve sampled the fruit of this the deep came bursting through, and tree in the Garden of Eden, they gained the windows of heaven were opened. the benefits of this knowledge, but (Genesis 7:11).” they were banished from the Garden. Knowledge can lead to good or evil, just Genesis goes on to say that the waters as the gamma rays — intended to further increased, and the comics used here all the cause of science — instead turn emphasize the upward movement of the scientist Bruce Banner into the mindless water as it lifts the ark, while two giraffes Hulk. I’ve used Incredible Hulk comics peek out at the tumult. There are small to address this duality. speech bubbles throughout that seem to tell parts of the story. Incredible Hulk (Kirby) Incredible Hulk: Tempest Fugit Flipper Hulk #280 Superboy Secret Invasion Aquaman Marvel Triple Action #11 Sub-Mariner Defenders #41 ROM the Space Knight World War Hulk Alpha Flight Hulk Annual #7 (Byrne) The Flood SOLD Theodore Herzl 2010 2010 10" x 13" 10" x 13" “The rain fell on the earth forty days and This portrait of Theodore Herzl is based forty nights. -

26 • November 1999 Spotlighting Kirby's Gods $5.95 in the US

#26 • November 1999 THE Spotlighting Kirby’s Gods $5.95 In The US Collector . c n I , s c i m o C C D © & M T s i t n a M , . c n I , s r e t c a r a h C l e v r a M © & M T s u t c a l a G THE ONLY ’ZINE AUTHORIZED BY THE Issue #26 Contents THE KIRBY ESTATE Jack Kirby On: ....................................6 (storytelling, man, God, and Nazis) Judaism .............................................11 (how did Jack’s faith affect his stories?) Jack Kirby’s Hercules ........................15 (this god was the ultimate hedonist) ISSUE #26, NOV. 1999 COLLECTOR A Failure To Communicate: Part 5 ....17 (a look at Journey Into Mystery #111) Kirby’s Golden Age Gods ..................20 (“It’s in the bag, All-Wisest!”) Myth-ing Pieces ................................22 (examining Kirby’s use of mythology) Theology of the New Gods ...............24 (the spiritual side of Jack’s opus) Fountain of Youth .............................30 (Kirby means never growing up) Jack Kirby: Mythmaker ....................31 (from Thor to the Eternals ) Stan Lee Presents: The Fourth World ...34 (pondering the ultimate “What If?”) Centerfold: Thor #144 pencils ...........36 Walt Simonson Interview .................39 (doing his damnedest on New Gods ) The Church of Stan & Jack ...............45 (the Bible & brotherhood, Marvel-style) Speak of the Devil .............................49 (how many times did Jack use him?) Kirby’s Ockhamistic Twist: Galactus ...50 (did the FF really fight God?) The Wisdom of the Watcher ............54 (putting on some weight, Watcher?) Kirby’s Trinity ...................................56 The Inheritance of Highfather ..........57 (Kirby & the Judeo-Christian doctrine) Forever Questioning .........................60 (comments on the Forever People) Life As Heroism ................................62 (is victory really sacrifice?) Classifieds .........................................66 Collector Comments .........................67 • Front cover inks: Vince Colletta ( Thor #134) • New Gods Concept Drawings (circa 1967): Pg.