Phd Dissertation Proposal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Futures and Options Workbook

EEXAMININGXAMINING FUTURES AND OPTIONS TABLE OF 130 Grain Exchange Building 400 South 4th Street Minneapolis, MN 55415 www.mgex.com [email protected] 800.827.4746 612.321.7101 Fax: 612.339.1155 Acknowledgements We express our appreciation to those who generously gave their time and effort in reviewing this publication. MGEX members and member firm personnel DePaul University Professor Jin Choi Southern Illinois University Associate Professor Dwight R. Sanders National Futures Association (Glossary of Terms) INTRODUCTION: THE POWER OF CHOICE 2 SECTION I: HISTORY History of MGEX 3 SECTION II: THE FUTURES MARKET Futures Contracts 4 The Participants 4 Exchange Services 5 TEST Sections I & II 6 Answers Sections I & II 7 SECTION III: HEDGING AND THE BASIS The Basis 8 Short Hedge Example 9 Long Hedge Example 9 TEST Section III 10 Answers Section III 12 SECTION IV: THE POWER OF OPTIONS Definitions 13 Options and Futures Comparison Diagram 14 Option Prices 15 Intrinsic Value 15 Time Value 15 Time Value Cap Diagram 15 Options Classifications 16 Options Exercise 16 F CONTENTS Deltas 16 Examples 16 TEST Section IV 18 Answers Section IV 20 SECTION V: OPTIONS STRATEGIES Option Use and Price 21 Hedging with Options 22 TEST Section V 23 Answers Section V 24 CONCLUSION 25 GLOSSARY 26 THE POWER OF CHOICE How do commercial buyers and sellers of volatile commodities protect themselves from the ever-changing and unpredictable nature of today’s business climate? They use a practice called hedging. This time-tested practice has become a stan- dard in many industries. Hedging can be defined as taking offsetting positions in related markets. -

Airline Scams and Scandals Free

FREE AIRLINE SCAMS AND SCANDALS PDF Edward Pinnegar | 160 pages | 09 Oct 2012 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752466255 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Airline Scams and Scandals by Edward Pinnegar | NOOK Book (eBook) | Barnes & Noble® We urge you to turn off your ad blocker for The Telegraph website so that you can continue to access our quality content in the future. Visit our adblocking instructions page. Telegraph Travel Galleries. Airline scams and scandals. Easyjet's idea of kosher When Easyjet announced a new route from London Luton to Tel Aviv found in Israel, a country where 76 per cent of the population are Jewish init also unveiled a special kosher menu designed by Hermolis of London, to be priced at the same Airline Scams and Scandals as standard ranges on other flights. However, in Februarymany Jewish passengers were somewhat taken aback Airline Scams and Scandals the inflight offering included bacon baguettes and ham melts. The airline claimed that the Airline Scams and Scandals food canisters had been loaded at Luton. But when the Airline Scams and Scandals thing happened two weeks later, Easyjet was forced to offer an official apology as well as issue staff with reminders as to the requirements of many passengers travelling to and from the Holy Land. Back to image. Travel latest. Latest advice as restrictions extended. Latest news on cruise lines and holidays. Everything you need to know about booking a trip this winter. Voucher Codes. The latest offers and discount codes from popular brands on Telegraph Voucher Codes. We've noticed you're adblocking. We rely on advertising to help fund our award-winning journalism. -

Seeking Income: Cash Flow Distribution Analysis of S&P 500

RESEARCH Income CONTRIBUTORS Berlinda Liu Seeking Income: Cash Flow Director Global Research & Design Distribution Analysis of S&P [email protected] ® Ryan Poirier, FRM 500 Buy-Write Strategies Senior Analyst Global Research & Design EXECUTIVE SUMMARY [email protected] In recent years, income-seeking market participants have shown increased interest in buy-write strategies that exchange upside potential for upfront option premium. Our empirical study investigated popular buy-write benchmarks, as well as other alternative strategies with varied strike selection, option maturity, and underlying equity instruments, and made the following observations in terms of distribution capabilities. Although the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Index (BXM), the leading buy-write benchmark, writes at-the-money (ATM) monthly options, a market participant may be better off selling out-of-the-money (OTM) options and allowing the equity portfolio to grow. Equity growth serves as another source of distribution if the option premium does not meet the distribution target, and it prevents the equity portfolio from being liquidated too quickly due to cash settlement of the expiring options. Given a predetermined distribution goal, a market participant may consider an option based on its premium rather than its moneyness. This alternative approach tends to generate a more steady income stream, thus reducing trading cost. However, just as with the traditional approach that chooses options by moneyness, a high target premium may suffocate equity growth and result in either less income or quick equity depletion. Compared with monthly standard options, selling quarterly options may reduce the loss from the cash settlement of expiring calls, while selling weekly options could incur more loss. -

Module 6 Option Strategies.Pdf

zerodha.com/varsity TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Orientation 1 1.1 Setting the context 1 1.2 What should you know? 3 2 Bull Call Spread 6 2.1 Background 6 2.2 Strategy notes 8 2.3 Strike selection 14 3 Bull Put spread 22 3.1 Why Bull Put Spread? 22 3.2 Strategy notes 23 3.3 Other strike combinations 28 4 Call ratio back spread 32 4.1 Background 32 4.2 Strategy notes 33 4.3 Strategy generalization 38 4.4 Welcome back the Greeks 39 5 Bear call ladder 46 5.1 Background 46 5.2 Strategy notes 46 5.3 Strategy generalization 52 5.4 Effect of Greeks 54 6 Synthetic long & arbitrage 57 6.1 Background 57 zerodha.com/varsity 6.2 Strategy notes 58 6.3 The Fish market Arbitrage 62 6.4 The options arbitrage 65 7 Bear put spread 70 7.1 Spreads versus naked positions 70 7.2 Strategy notes 71 7.3 Strategy critical levels 75 7.4 Quick notes on Delta 76 7.5 Strike selection and effect of volatility 78 8 Bear call spread 83 8.1 Choosing Calls over Puts 83 8.2 Strategy notes 84 8.3 Strategy generalization 88 8.4 Strike selection and impact of volatility 88 9 Put ratio back spread 94 9.1 Background 94 9.2 Strategy notes 95 9.3 Strategy generalization 99 9.4 Delta, strike selection, and effect of volatility 100 10 The long straddle 104 10.1 The directional dilemma 104 10.2 Long straddle 105 10.3 Volatility matters 109 10.4 What can go wrong with the straddle? 111 zerodha.com/varsity 11 The short straddle 113 11.1 Context 113 11.2 The short straddle 114 11.3 Case study 116 11.4 The Greeks 119 12 The long & short straddle 121 12.1 Background 121 12.2 Strategy notes 122 12..3 Delta and Vega 128 12.4 Short strangle 129 13 Max pain & PCR ratio 130 13.1 My experience with option theory 130 13.2 Max pain theory 130 13.3 Max pain calculation 132 13.4 A few modifications 137 13.5 The put call ratio 138 13.6 Final thoughts 140 zerodha.com/varsity CHAPTER 1 Orientation 1.1 – Setting the context Before we start this module on Option Strategy, I would like to share with you a Behavioral Finance article I read couple of years ago. -

Income Solutions: the Case for Covered Calls an Advantageous Strategy for a Low-Yield World

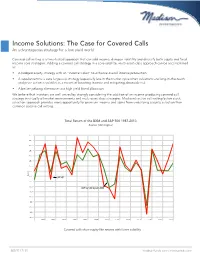

Income Solutions: The Case for Covered Calls An advantageous strategy for a low-yield world Covered call writing is a time-tested approach that can add income, dampen volatility and diversify both equity and fixed income core strategies. Adding a covered call strategy in a core-satellite, multi-asset-class approach can be accomplished as: • A hedged equity strategy with an “income kicker” to enhance overall income production • A supplement to a core large-cap strategy (especially late in the market cycle when valuations are long-in-the-tooth and price action is volatile) as a means of boosting income and mitigating downside risk • A better-yielding alternative to a high yield bond allocation We believe that investors are well-served by strongly considering the addition of an income-producing covered call strategy in virtually all market environments and multi-asset class strategies. Madison’s active call writing/active stock selection approach provides more opportunity for premium income and alpha from underlying security selection than common passive call writing. Total Return of the BXM and S&P 500 1987-2013 Rolling Returns Source: Morningstar Time Period: 1/1/1987 to 12/31/2013 Rolling Window: 1 Year 1 Year shift 40.0 35.0 30.0 25.0 20.0 15.0 10.0 5.0 Return 0.0 S&P 500 -5.0 -10.0 CBOE S&P 500 Buywrite BXM -15.0 -20.0 -25.0 -30.0 -35.0 -40.0 1989 1991 1993 1995 1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 S&P 500 TR USD Covered calls show equity-likeCBOE returns S&P 500 with Buyw ritelower BXM volatility Source: Morningstar Direct 888.971.7135 madisonfunds.com | madisonadv.com Covered Call Strategy(A) Benefits of Individual Stock Options vs. -

Options Strategy Guide for Metals Products As the World’S Largest and Most Diverse Derivatives Marketplace, CME Group Is Where the World Comes to Manage Risk

metals products Options Strategy Guide for Metals Products As the world’s largest and most diverse derivatives marketplace, CME Group is where the world comes to manage risk. CME Group exchanges – CME, CBOT, NYMEX and COMEX – offer the widest range of global benchmark products across all major asset classes, including futures and options based on interest rates, equity indexes, foreign exchange, energy, agricultural commodities, metals, weather and real estate. CME Group brings buyers and sellers together through its CME Globex electronic trading platform and its trading facilities in New York and Chicago. CME Group also operates CME Clearing, one of the largest central counterparty clearing services in the world, which provides clearing and settlement services for exchange-traded contracts, as well as for over-the-counter derivatives transactions through CME ClearPort. These products and services ensure that businesses everywhere can substantially mitigate counterparty credit risk in both listed and over-the-counter derivatives markets. Options Strategy Guide for Metals Products The Metals Risk Management Marketplace Because metals markets are highly responsive to overarching global economic The hypothetical trades that follow look at market position, market objective, and geopolitical influences, they present a unique risk management tool profit/loss potential, deltas and other information associated with the 12 for commercial and institutional firms as well as a unique, exciting and strategies. The trading examples use our Gold, Silver -

Eaton Vance Tax-Advantaged Bond and Option Strategies Fund Notice

Eaton Vance Tax-Advantaged Bond and Option Strategies Fund Notice of Changes to Fund Name, Investment Objective, Fees and Distributions The Board of Trustees of Eaton Vance Tax-Advantaged Bond and Option Strategies Fund (NYSE: EXD) (the “Fund”) has approved changes to the Fund’s name, investment objective and investment policies as described below. In connection with these changes, the portfolio managers of the Fund will change and the Fund’s investment advisory fee rate will be reduced. Each of the foregoing changes will be effective on or about February 8, 2019. Following implementation of the changes to the Fund’s investment objective and policies, the Fund will increase the frequency of its shareholder distributions from quarterly to monthly and raise the distribution rate as described below. Name. The Fund’s name will change to “Eaton Vance Tax-Managed Buy-Write Strategy Fund.” It will continue to be listed on the New York Stock Exchange under the ticker symbol “EXD.” Investment Objectives. As revised, the Fund will have a primary objective to provide current income and gains, with a secondary objective of capital appreciation. In pursuing its investment objectives, the Fund will evaluate returns on an after-tax basis, seeking to minimize and defer shareholder federal income taxes. There can be no assurance that the Fund will achieve its investment objectives. The Fund’s current investment objective is tax-advantaged income and gains. Principal Investment Policies. The Fund currently employs a tax-advantaged short-term bond strategy (“Bond Strategy”) and a rules-based option overlay strategy that consists of writing a series of put and call spreads on the S&P 500 Composite Stock Price Index® (the “S&P 500”) (“Option Overlay Strategy”). -

Invesco S&P 500 Buywrite

PBP As of June 30, 2021 Invesco S&P 500 BuyWrite ETF Fund description Growth of $10,000 The The Invesco S&P 500 Index BuyWrite ETF Invesco S&P 500 BuyWrite ETF: $18,357 (Fund) is based on the CBOE S&P 500 BuyWrite Cboe S&P 500 BuyWrite Index: $19,691 IndexTM (Index). The Fund generally will invest at S&P 500 Index: $39,893 least 90% of its total assets in securities that $55K comprise the Index and will write (sell) call options thereon. The Index is a total return benchmark index that is designed to track the performance of $40K a hypothetical "buy-write" strategy on the S&P 500® Index. The Index measures the total rate of return of an S&P 500 covered call strategy. This $25K strategy consists of holding a long position indexed to the S&P 500 Index and selling a succession of covered call options, each with an exercise price at or above the prevailing price level $10K of the S&P 500 Index. Dividends paid on the component stocks underlying the S&P 500 Index and the dollar value of option premiums received from written options are reinvested. The Fund and 06/11 12/12 05/14 10/15 03/17 08/18 01/20 06/21 the Index are rebalanced and reconstituted Data beginning 10 years prior to the ending date of June 30, 2021. Fund performance shown at NAV. quarterly. Performance as at June 30, 2021 Performance (%) Fund ETF Information YTD 1Y 3Y 5Y 10Y Inception Fund Name Invesco S&P 500 BuyWrite ETF ETF - NAV 10.76 26.46 4.82 6.39 6.26 4.18 Fund Ticker PBP ETF - Market Price 11.15 26.56 4.72 6.41 6.25 4.18 CUSIP 46137V399 Underlying Index 11.10 27.28 -

Options Application (PDF)

Questions? Go to Fidelity.com/options. Options Application Use this application to apply to add options trading to your new or existing Fidelity account. If you already have options trading on your account, use this application to add or update account owner or authorized agent information. Please complete in CAPITAL letters using black ink. If you need more room for information or signatures, make a copy of the relevant page. Helpful to Know Requirements – Margin can involve significant cost and risk and is not • Entire form must be completed in order to be considered appropriate for all investors. Account owners must for Options. If you are unsure if a particular section pertains determine whether margin is consistent with their investment to you, please call a Fidelity investment professional at objectives, income, assets, experience, and risk tolerance. 800-343-3548. No investment or use of margin is guaranteed to achieve any • All account owners must complete the account owner sections particular objective. and sign Section 5. – Margin will not be granted if we determine that you reside • Any authorized agent must complete Section 6 and sign outside of the United States. Section 7. – Important documents related to your margin account include • Trust accounts must provide trustee information where the “Margin Agreement” found in the Important Information information on account owners is required. about Margins Trading and Its Risks section of the Fidelity Options Agreement. Eligibility of Trading Strategies Instructions for Corporations and Entities Nonretirement accounts: • Unless options trading is specifically permitted in the corporate • Business accounts: Eligible for any Option Level. -

EQUITY DERIVATIVES Faqs

NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF SECURITIES MARKETS SCHOOL FOR SECURITIES EDUCATION EQUITY DERIVATIVES Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) Authors: NISM PGDM 2019-21 Batch Students: Abhilash Rathod Akash Sherry Akhilesh Krishnan Devansh Sharma Jyotsna Gupta Malaya Mohapatra Prahlad Arora Rajesh Gouda Rujuta Tamhankar Shreya Iyer Shubham Gurtu Vansh Agarwal Faculty Guide: Ritesh Nandwani, Program Director, PGDM, NISM Table of Contents Sr. Question Topic Page No No. Numbers 1 Introduction to Derivatives 1-16 2 2 Understanding Futures & Forwards 17-42 9 3 Understanding Options 43-66 20 4 Option Properties 66-90 29 5 Options Pricing & Valuation 91-95 39 6 Derivatives Applications 96-125 44 7 Options Trading Strategies 126-271 53 8 Risks involved in Derivatives trading 272-282 86 Trading, Margin requirements & 9 283-329 90 Position Limits in India 10 Clearing & Settlement in India 330-345 105 Annexures : Key Statistics & Trends - 113 1 | P a g e I. INTRODUCTION TO DERIVATIVES 1. What are Derivatives? Ans. A Derivative is a financial instrument whose value is derived from the value of an underlying asset. The underlying asset can be equity shares or index, precious metals, commodities, currencies, interest rates etc. A derivative instrument does not have any independent value. Its value is always dependent on the underlying assets. Derivatives can be used either to minimize risk (hedging) or assume risk with the expectation of some positive pay-off or reward (speculation). 2. What are some common types of Derivatives? Ans. The following are some common types of derivatives: a) Forwards b) Futures c) Options d) Swaps 3. What is Forward? A forward is a contractual agreement between two parties to buy/sell an underlying asset at a future date for a particular price that is pre‐decided on the date of contract. -

Arbitrage Spread.Pdf

Arbitrage spreads Arbitrage spreads refer to standard option strategies like vanilla spreads to lock up some arbitrage in case of mispricing of options. Although arbitrage used to exist in the early days of exchange option markets, these cheap opportunities have almost completely disappeared, as markets have become more and more efficient. Nowadays, millions of eyes as well as computer software are hunting market quote screens to find cheap bargain, reducing the life of a mispriced quote to a few seconds. In addition, standard option strategies are now well known by the various market participants. Let us review the various standard arbitrage spread strategies Like any trades, spread strategies can be decomposed into bullish and bearish ones. Bullish position makes money when the market rallies while bearish does when the market sells off. The spread option strategies can decomposed in the following two categories: Spreads: Spread trades are strategies that involve a position on two or more options of the same type: either a call or a put but never a combination of the two. Typical spreads are bull, bear, calendar, vertical, horizontal, diagonal, butterfly, condors. Combination: in contrast to spreads combination trade implies to take a position on both call and puts. Typical combinations are straddle, strangle1, and risk reversal. Spreads (bull, bear, calendar, vertical, horizontal, diagonal, butterfly, condors) Spread trades are a way of taking views on the difference between two or more assets. Because the trading strategy plays on the relative difference between different derivatives, the risk and the upside are limited. There are many types of spreads among which bull, bear, and calendar, vertical, horizontal, diagonal, butterfly spreads are the most famous. -

Options Trading Strategy Based on ARIMA Forecasting

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/2399-1747.htm Options Options trading strategy based on trading ARIMA forecasting strategy Pierre Rostan Department of Business, American University of Afghanistan, Kabul, Afghanistan 111 Alexandra Rostan American University of Afghanistan, Kabul, Afghanistan, and Received 13 July 2019 Revised 1 January 2020 Mohammad Nurunnabi Accepted 23 April 2020 Department of Accounting, Prince Sultan University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia Abstract Purpose – The purpose of this paper is to illustrate a profitable and original index options trading strategy. Design/methodology/approach – The methodology is based on auto regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) forecasting of the S&P 500 index and the strategy is tested on a large database of S&P 500 Composite index options and benchmarked to the generalized auto regressive conditional heteroscedastic (GARCH) model. The forecasts validate a set of criteria as follows: the first criterion checks if the forecasted index is greater or lower than the option strike price and the second criterion if the option premium is underpriced or overpriced. A buy or sell and hold strategy is finally implemented. Findings – The paper demonstrates the valuable contribution of this option trading strategy when trading call and put index options. It especially demonstrates that the ARIMA forecasting method is a valid method for forecasting the S&P 500 Composite index and is superior to the GARCH model in the context of an application to index options trading. Originality/value – The strategy was applied in the aftermath of the 2008 credit crisis over 60 months when the volatility index (VIX) was experiencing a downtrend.