LARGE-SCALE DEVELOPMENT PROJECTS in the VENEZUELAN ORINOCO WATERSHED and THEIR ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STUDIES by J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Judgment of 18 December 2020

18 DECEMBER 2020 JUDGMENT ARBITRAL AWARD OF 3 OCTOBER 1899 (GUYANA v. VENEZUELA) ___________ SENTENCE ARBITRALE DU 3 OCTOBRE 1899 (GUYANA c. VENEZUELA) 18 DÉCEMBRE 2020 ARRÊT TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraphs CHRONOLOGY OF THE PROCEDURE 1-22 I. INTRODUCTION 23-28 II. HISTORICAL AND FACTUAL BACKGROUND 29-60 A. The Washington Treaty and the 1899 Award 31-34 B. Venezuela’s repudiation of the 1899 Award and the search for a settlement of the dispute 35-39 C. The signing of the 1966 Geneva Agreement 40-44 D. The implementation of the Geneva Agreement 45-60 1. The Mixed Commission (1966-1970) 45-47 2. The 1970 Protocol of Port of Spain and the moratorium put in place 48-53 3. From the good offices process (1990-2014 and 2017) to the seisin of the Court 54-60 III. INTERPRETATION OF THE GENEVA AGREEMENT 61-101 A. The “controversy” under the Geneva Agreement 64-66 B. Whether the Parties gave their consent to the judicial settlement of the controversy under Article IV, paragraph 2, of the Geneva Agreement 67-88 1. Whether the decision of the Secretary-General has a binding character 68-78 2. Whether the Parties consented to the choice by the Secretary-General of judicial settlement 79-88 C. Whether the consent given by the Parties to the judicial settlement of their controversy under Article IV, paragraph 2, of the Geneva Agreement is subject to any conditions 89-100 IV. JURISDICTION OF THE COURT 102-115 A. The conformity of the decision of the Secretary-General of 30 January 2018 with Article IV, paragraph 2, of the Geneva Agreement 103-109 B. -

FRESH-WATER SHRIMPS (CRUSTACEA, DECAPODA, NATANTIA) of the ORINOCO BASIN and the VENEZUELAN GUAYANA Gilberto Rodriguez the Guaya

JOURNAL OF CRUSTACEAN BIOLOGY, 2(3): 378-391, 1982 FRESH-WATER SHRIMPS (CRUSTACEA, DECAPODA, NATANTIA) OF THE ORINOCO BASIN AND THE VENEZUELAN GUAYANA Gilberto Rodriguez ABSTRACT Shrimps of the families Sergestidae and Palaemonidae collected in the Orinoco basin, the upper Cuyuni River, and the upper and lower Rio Negro, are dealt with in this paper. New records and comments are given for Acetes paraguayensis, Macrobrachium amazonicum, M. brasiliense, M. jelskii, M. nattered, M. surinamicum, and Palaemonetes carteri. Two new palaemonids are described: Macrobrachium cortezi, a form related to M. nattereri, from several localities in the Orinoco River and upper Rio Negro, and M. aracamuni, from an altitude of 680 m in the Cerro Aracamuni in the drainage area of the upper Rio Negro. Another previously undescribed species of Macrobrachium is recorded but not named due to the lack of mature males. The Guayana highland is an ancient land mass extending from the Amazon River to the Atlantic coast of South America and includes the Guianas and parts of Venezuela and Brazil. The Venezuelan Guayana comprises 41,300 km2 of territory, mostly above 400 m that separate the Orinoco from the Amazon basin and forms a formidable barrier to the dispersion of the fresh-water fauna of the lowlands. The hydrology of the zone is defined by the Orinoco River that bounds the area to the west and north and its tributaries that generally flow north or northwesterly. A smaller portion to the east is drained by the Cuyuni River. The Orinoco and the Amazon basins are connected through the Brazo Casiquiare, while the inundated savannah of Rupununi allows intermittent connections be tween the Branco and the Esequibo Rivers (Lowe-McConnell, 1964). -

(Inia and Sotalia) in the Amazon and Orinoco River Basins

MARINE MAMMAL SCIENCE, **(*): ***–*** (*** 2011) C ! 2011 by the Society for Marine Mammalogy DOI: 10.1111/j.1748-7692.2011.00468.x Population, density estimates, and conservation of river dolphins (Inia and Sotalia) in the Amazon and Orinoco river basins CATALINA GOMEZ-SALAZAR Biology Department, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 4J1, Canada and Foundation Omacha, Calle 86A No. 23-38, Bogota, Colombia E-mail: [email protected] FERNANDO TRUJILLO Foundation Omacha, Calle 86A No. 23-38, Bogota, Colombia MARCELA PORTOCARRERO-AYA Foundation Omacha, Calle 86A No. 23-38, Bogota, Colombia and Hull International Fisheries Institute, The University of Hull, Hull, HU6 7RX, United Kingdom HAL WHITEHEAD Biology Department, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H4J1, Canada ABSTRACT This study is part of an on-going effort to evaluate and monitor river dolphin populations in South America. It comprises the largest initiative to estimate pop- ulation size and densities of Inia and Sotalia dolphins using statistically robust and standardized methods. From May 2006 to August 2007, seven visual surveys were conducted in selected large rivers of Bolivia, Colombia, Brazil, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela in the Amazon and Orinoco river basins. Population sizes of Inia and Sotalia were estimated for different habitats (main river, tributary, lake, is- land, confluence, and channel). A total of 291 line and 890 strip transects were conducted, covering a distance of 2,704 linear kilometers. We observed 778 Inia geoffrensis,1,323Inia boliviensis,and764Sotalia fluviatilis.High-densityareaswere identified (within 200 m from the river banks, confluences, and lakes) and we pro- pose that these constitute critical habitat for river dolphins. -

Full Text in Pdf Format

Vol. 45: 269–282, 2021 ENDANGERED SPECIES RESEARCH Published July 29 https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01133 Endang Species Res OPEN ACCESS Home range and movements of Amazon river dolphins Inia geoffrensis in the Amazon and Orinoco river basins Federico Mosquera-Guerra1,2,*, Fernando Trujillo1, Marcelo Oliveira-da-Costa3, Miriam Marmontel4, Paul André Van Damme5, Nicole Franco1, Leslie Córdova5, Elizabeth Campbell6,7,8, Joanna Alfaro-Shigueto6,7,8, José Luis Mena9, Jeffrey C. Mangel6,7,8, José Saulo Usma Oviedo3, Juan D. Carvajal-Castro10,11, Hugo Mantilla-Meluk12,13, Dolors Armenteras-Pascual2 1Fundación Omacha, 111211 Bogotá, D.C., Colombia 2Grupo de Ecología del Paisaje y Modelación de Ecosistemas-ECOLMOD, Departamento de Biología, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 111321 Bogotá, D.C., Colombia 3World Wildlife Fund (WWF) − Brazil, Colombia, and Peru, Rue Mauverney 28, 1196 Gland, Switzerland 4Instituto de Desenvolvimento Sustentável Mamirauá, 69.553-225 Tefé (AM), Brazil 5Faunagua, 31001 Sacaba-Cochabamba, Bolivia 6ProDelphinus, 15074 Lima, Peru 7School of BioSciences, University of Exeter, Penryn, Cornwall TR10 9EZ, UK 8Carrera de Biología Marina, Universidad Cientifíca del Sur, 15067 Lima, Peru 9Museo de Historia Natural Vera Alleman Haeghebaert, Universidad Ricardo Palma, 1801 Lima, Peru 10Grupo de Investigación en Evolución, Ecología y Conservación (EECO), Programa de Biología, Universidad del Quindío, 630004 Armenia, Colombia 11Department of Biological Sciences, St. John’s University, 11366 Queens, NY, USA 12Grupo de Investigación en Desarrollo y Estudio del Recurso Hídrico y el Ambiente (CIDERA), Programa de Biología, Universidad del Quindío, 630004 Armenia, Colombia 13Centro de Estudios de Alta Montaña, Universidad del Quindío, 630004 Armenia, Colombia ABSTRACT: Studying the variables that describe the spatial ecology of threatened species allows us to identify and prioritize areas that are critical for species conservation. -

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian Tributaries of the Orinoco

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian tributaries of the Orinoco The Orinoco Basin Health Report Card was officially kicked-off in June 2015 with the first stakeholder engagement meeting in Puerto López, in the Orinoquía Region of Meta Department, Colombia. More than 40 representatives from 19 organizations attended the workshop aimed at identifying the environmental, social and economic indicators that will form the basis of the Meta River Report Card. Indicators were chosen based on the top values identified as key to the future sustainability of the Meta River basin. Participating institutions included the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Humboldt Institute, Corporinoquia, Omacha Foundation, Fundacion Orinoco, WWF, among others. The three-day interactive workshop also attracted positive media attention. Outcomes from the meeting included: 1. Identification, and ranking by importance, of environmental, social and economic values within the Meta River basin. 2. Identification, and ranking by importance, of threats to identified values within the Meta River basin. 3. Choice of indicators for measuring/reporting the status of these values and threats. 4. Assignment of key personnel to work on developing each indicator and defining benchmarks for scoring against. ? 5. A time line through to completion and public release in early next 2016. ? Reporting regions The 804 km length of the Meta River traverses a variety of elevations and ecosystem types ? from its origins in the Andes to it’s confluence with the Orinoco River, near Puerto Carreño in the east. Hence, it is anticipated that the river will be divided into three reporting regions, each being assessed and scored independently of each other. -

(Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygonidae) of the Amazon, Orinoco, Magdalena

Molecular systematics of the freshwater stingrays (Myliobatiformes: Potamotrygonidae) of the Amazon, Orinoco, Magdalena, Esequibo, Caribe and Maracaibo basins (Colombia- Venezuela): evidence from mitochondrial genes David García*, Carlos Lasso+ and Susana Caballero* *Laboratorio de Ecología Molecular de Vertebrados Acuáticos. Universidad de los Andes, Colombia e-mail: [email protected] +Instituto de Investigación de Recursos Biológicos Alexander von Humboldt, Colombia Abstract Freshwater stingrays from the family Potamotrygonidae have a restricted distribution to the freshwater systems of South America. Lack of adequate information about the taxonomic and evolutionary relationships, ecology, biology and distribution of several species belonging to this family makes them vulnerable to anthropic activities, including commercial exploitation for the ornamental fish market. Samples were collected from the main river basins in Colombia and Venezuela (Amazon, Orinoco, Magdalena, Esequibo, Caribe and Maracaibo) for four genera and seven species of the family (Heliotrygon gomesi, Paratrygon aiereba, Plesiotrygon iwamae, Potamotrygon motoro, Potamotrygon yepezi, Potamotrygon schroederi, Potamotrygon magdalenae), and some unidentified species. Molecular markers Cytochrome Oxidase subunit I, Cytochrome b and ATPase subunit 6 were amplified and sequenced. Maximum likelihood and Bayesian Inference analysis were performed to obtain topologies for each marker and for a concatenated dataset including the three genes. Small dataset may compromise some methods estimations of sequence divergence in the ATP6 marker. Monophyly of the four genera in the Potamotrygonidae family was confirmed and phylogenetic relations among member of the Potamotrygon genus were not clearly resolved. However, results obtained with the molecular marker Cytb appear to offer a good starting point to differentiate among genera and species as a tool that could be used for fast molecular identification (Barcode). -

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian Tributaries of the Orinoco

Report Card of the Meta River Basin, Colombia Evaluation of Colombian tributaries of the Orinoco The Orinoco Basin Health Report Card was officially kicked-off in June 2015 with the first stakeholder engagement meeting in Puerto López, Reporting regions in the Orinoquía Region of Meta Department, Colombia. The 804 km length of the Meta River traverses a More than 40 representatives from 19 organizations attended the variety of elevations and ecosystem types from it’s workshop. During the workshop the environmental, social and origins in the Andes to it’s confluence with the economic indicators that will form the basis of the Meta River Report Orinoco River, near Puerto Carreño in the east. Card were identified. Indicators were chosen based on the top values Hence, it is anticipated that the river will be divided identified as key to the future sustainability of the Meta River basin. into three reporting regions, each being assessed We appreciate the continued active participation of the following and scored independently of each other. organizations with environmental authorities that will enable the completion of the report: the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Preliminary discussions were held on how best to Development, the Von Humboldt Institute, Corporinoquia, Omacha define these regions and it was generally accepted Foundation, National Authority for Aquaculture and Fisheries, the to achieve this based on elevation changes. A Palmita Reserve Foundation, Javeriana University, University of the technical group has been established to define and Llanos, Palmarito Foundation, Ocelot Foundation, Calidris Foundation, document these regions. Foundation Orinoco Biodiversa, Federation National Cattlemen, Corpochivor, Nature Reserve The Pedregoza, Orinoquia Foundation, University of Maryland and WWF. -

The Orinoco Oil Belt - Update

THE ORINOCO OIL BELT - UPDATE Figure 1. Map showing the location of the Orinoco Oil Belt Assessment Unit (blue line); the La Luna-Quercual Total Petroleum System and East Venezuela Basin Province boundaries are coincident (red line). Source: http://geology.com/usgs/venezuela-heavy-oil/venezuela-oil-map-lg.jpg Update on extra heavy oil development in Venezuela 2012 is likely to be a crucial year for the climate, as Venezuela aims to ramp up production of huge reserves of tar sands-like crude in the eastern Orinoco River Belt.i Venezuela holds around 90% of proven extra heavy oil reserves globally, mainly located in the Orinoco Belt. The Orinoco Belt extends over a 55,000 Km2 area, to the south of the Guárico, Anzoátegui, Monagas, and Delta Amacuro states (see map). It contains around 256 billion barrels of recoverable crude, according to state oil company PDVSA.ii Certification of this resource means that, in July 2010, Venezuela overtook Saudia Arabia as the country with the largest oil reserves in the world.iii Petróleos de Venezuela SA (PDVSA), the state oil company, is also now the world’s fourth largest company.iv Development of the Orinoco Belt is the keystone of the Venezuelan government’s future economic plans – oil accounts for 95% of the country’s export earnings and around 55% of the federal budget.v The government has stated that it is seeking $100 billion of new investment to develop the Belt.vi President Chavez announced at the end of 2011 that the country intended to boost its oil output to 3.5 million barrels a day by the end of 2012. -

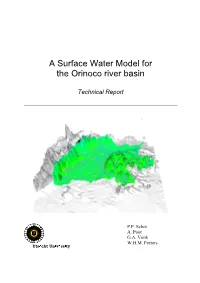

A Surface Water Model for the Orinoco River Basin

A Surface Water Model for the Orinoco river basin Technical Report P.P. Schot A. Poot G.A. Vonk W.H.M. Peeters 2 A Surface Water Model for the Orinoco river basin Technical Report P.P. Schot A. Poot G.A. Vonk W.H.M. Peeters Utrecht, March 2001 Department of Environmental Sciences Faculty of Geography Utrecht University P.O.Box 80.115 3508 TC Utrecht The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 3 4 Contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................................. 6 LIST OF TABLES ................................................................................................................... 7 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 9 2 STUDY AREA ................................................................................................................ 10 2.1 General description................................................................................................ 10 2.2 Climate .................................................................................................................. 10 2.3 Hydrology.............................................................................................................. 12 3 GENERAL MODEL DESCRIPTION.......................................................................... 16 3.1 Model concept ....................................................................................................... 16 3.2 Model input .......................................................................................................... -

Lowland Vegetation of Tropical South America -- an Overview

Lowland Vegetation of Tropical South America -- An Overview Douglas C. Daly John D. Mitchell The New York Botanical Garden [modified from this reference:] Daly, D. C. & J. D. Mitchell 2000. Lowland vegetation of tropical South America -- an overview. Pages 391-454. In: D. Lentz, ed. Imperfect Balance: Landscape Transformations in the pre-Columbian Americas. Columbia University Press, New York. 1 Contents Introduction Observations on vegetation classification Folk classifications Humid forests Introduction Structure Conditions that suppport moist forests Formations and how to define them Inclusions and archipelagos Trends and patterns of diversity in humid forests Transitions Floodplain forests River types Other inundated forests Phytochoria: Chocó Magdalena/NW Caribbean Coast (mosaic type) Venezuelan Guayana/Guayana Highland Guianas-Eastern Amazonia Amazonia (remainder) Southern Amazonia Transitions Atlantic Forest Complex Tropical Dry Forests Introduction Phytochoria: Coastal Cordillera of Venezuela Caatinga Chaco Chaquenian vegetation Non-Chaquenian vegetation Transitional vegetation Southern Brazilian Region Savannas Introduction Phytochoria: Cerrado Llanos of Venezuela and Colombia Roraima-Rupununi savanna region Llanos de Moxos (mosaic type) Pantanal (mosaic type) 2 Campo rupestre Conclusions Acknowledgments Literature Cited 3 Introduction Tropical lowland South America boasts a diversity of vegetation cover as impressive -- and often as bewildering -- as its diversity of plant species. In this chapter, we attempt to describe the major types of vegetation cover in this vast region as they occurred in pre- Columbian times and outline the conditions that support them. Examining the large-scale phytogeographic regions characterized by each major cover type (see Fig. I), we provide basic information on geology, geological history, topography, and climate; describe variants of physiognomy (vegetation structure) and geography; discuss transitions; and examine some floristic patterns and affinities within and among these regions. -

The Guiana Shield

THIRTEEN The Guiana Shield NATHAN K. LUJAN and JONATHAN W. ARMBRUSTER Highland areas that serve as sources and boundaries for the a superfamily sister to all other Siluriformes, and their bio- great rivers of South America can be broadly divided into two geographic tractability due to distributions across headwater categories based on their geologic age and origin. As reviewed habitats and associated allopatric distribution patterns among elsewhere in this volume (Chapters 15 and 16), the allochtho- sister taxa. We conclude that the diverse loricariid fauna of the nous terrains and massive crustal deformations of the Andes Guiana Shield accumulated gradually over tens of millions of Mountains that comprise the extremely high-elevation west- years with major lineages being shaped by geologic evolution ern margin of South America have their origins in diastrophic across the whole continent, and not as the result of a rapid, (distortional) tectonic activity largely limited to the Late Paleo- geographically restricted adaptive radiation. We demonstrate gene and Neogene (<25 Ma; Gregory-Wodzicki 2000). In con- the role of the Guiana and Brazilian shields as ancient reser- trast, vast upland regions across much of the interior of the voirs of high-gradient lotic habitats infl uencing the origin of continent have been relatively tectonically quiescent since the frequently rheophilic loricariid taxa. We also show how diver- Proterozoic (>550 Ma; Gibbs and Baron 1993) and exhibit a sifi cation was infl uenced by a restricted number of landscape topography that is instead largely the result of nondeforma- scale features: especially dispersal and vicariance across several tional, epeirogenic uplift of the Guiana and Brazilian shields geologically persistent corridors, expansion and contraction of and subsequent erosion of overlying sedimentary formations. -

Orinoco Delta Is a Vast River Delta of the Orinoco River, Located in Eastern Venezuela

The River and its people The Orinoco is one of the longest rivers in South America at 2,140 kilometres (1,330 mi). Its drainage basin, sometimes called the Orinoquia, covers 880,000 square kilometres (340,000 sq mi), with 76.3 percent of it in Venezuela and the remainder in Colombia. The Orinoco and its tributaries are the major transportation system for eastern and interior Venezuela and the llanos of Colombia. The Orinoco is extremely diverse and hosts a wide variety of flora and fauna. The Orinoco Delta is a vast river delta of the Orinoco River, located in eastern Venezuela. The delta includes large areas of permanent wetlands as well as seasonally-flooded freshwater swamp forests. The river margins of the delta are fringed with mangroves. Also, daily tides bring upstream – the "caños" – sea water which is responsible for the "macareo" or pororoca and also for inversion of flow direction of water, at least, on its surface. The Orinoco Delta is characterized by being non-centric, lagoon lacking and oceanic. Alexander von Humboldt explored the basin in 1800, reporting on the pink river dolphins. He published extensively on the river's flora and fauna. The Warao are an indigenous people inhabiting northeastern Venezuela and western Guyana. Alternate common spellings of Warao are Waroa, Guarauno, Guarao, and Warrau. The term Warao translates as "the boat people," after the Warao's lifelong and intimate connection to the water. Most of the approximately 20,000 Warao inhabit Venezuela's Orinoco Delta region, with smaller numbers in neighboring Guyana and Suriname. They speak an agglutinative language, Warao.