Background Context and Observation Recording

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

White Rann – Kalo Dungar Day Tour

Tour Code : AKSR0142 Tour Type : FIT Package 1800 233 9008 MATA NO MADH – WHITE www.akshartours.com RANN – KALO DUNGAR DAY TOUR 0 Nights / 1 Days PACKAGE OVERVIEW 1Country 3Cities 1Days 3Activities Accomodation Meal NO ACCOMODATION NO MEALS Highlights Visa & Taxes Accommodation on double sharing Breakfast and dinner at hotel 5 % GST Extra Transfer and sightseeing by pvt vehicle as per program Applicable hotel taxes SIGHTSEEINGS OVERVIEW - Mata no madh - Kalo dungar - White rann SIGHTSEEINGS Kalo Dungar - Dattatreya Temple Kalo Dungar Alias Black Hill Is The Highest Point Of The Kutch Region, Offering The Bird's-Eye View Of The Great Rann Of Kutch. At Only 462 Meters, The Hill Itself Is An Easy Climb And Can Be Reached By Either Hopping In Private Taxi Or Gujarat Tourism Buses. Dattatreya Temple, A 400-Year-Old Shrine Sacred To Lord Dattatreya Is Noticeable On The Top Of The Hill. Many Fables And Tales Are Associated With The History Of The Kalo Dungar, One Of Them Say That Dattatreya, The Three-Headed Incarnation Of Lord Brahma, Lord Vishnu And Lord Shiva In The Same Body, Stopped At This Hill While Walking On The Earth. On The Hills, He Noticed Many Hungry Jackals And Offered Them His Body To Eat. When Jackals Started Eating Dattatreya's Body, His Body Automatically Regenerated. The Practice Of Feeding Jackals Is Still Practiced By The People. Priest Of The Temple Prepares Food And Serve It To Jackals Each Morning And Evening, After The Aarti (Hindu Religious Ritual Of Worship). There Is A Bhojnalaya Too That Brings People From All Walks Of Life To Eat A Meal Together, Free Of Cost. -

SACRED and NON-SACRED LANDSCAPES in NEPAL by Deen Bandhu Bhatta

ABSTRACT COMMUNITY APPROACHES TO NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT: SACRED AND NON-SACRED LANDSCAPES IN NEPAL by Deen Bandhu Bhatta This study examines the different kinds of management approaches practiced by local people in far-western Nepal for the management and conservation of two kinds of forests, sacred groves and community forests. It reveals the role of traditional religious beliefs, property rights, and the central government, as well as the importance of traditional ecological knowledge and local participation in management and conservation of the natural resources. In Nepal, the ties of local people with the forest are strong and inseparable. Forest management is an important part of the local livelihood strategies. Local forest management is based on either religious and cultural or utilitarian components of the local community. Management of the sacred grove is integrated with the religious and cultural aspects, whereas the management of the community forest is associated with the utility aspects. Overall, the management strategies applied depend on the needs of the local people. COMMUNITY APPROACHES TO NATURAL RESOURCES MANAGEMENT: SACRED AND NON-SACRED LANDSCAPES IN NEPAL A Practicum Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Environmental Science Institute of Environmental Sciences By Deen Bandhu Bhatta Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2003 Advisor___________________________ Adolph Greenberg Reader______________________________ Gene Willeke Reader_____________________________ -

Ecology and Management of Sacred Groves in Kerala, India

Forest Ecology and Management 112 (1998) 165±177 Ecology and management of sacred groves in Kerala, India U.M. Chandrashekara*, S. Sankar Kerala Forest Research Institute, Peechi 680 653, Kerala, India Received 10 September 1997; accepted 5 May 1998 Abstract In Kerala, based on management systems, sacred groves can be categorised into three groups namely those managed by individual families, by groups of families and by the statutory agencies for temple management (Devaswom Board). Ollur Kavu, S.N. Puram Kavu and Iringole Kavu which represent above mentioned management systems, respectively, were studied for their tree species composition and vegetation structure. The study was also designed to assess the strengths and weaknesses of present management systems and role of different stakeholder groups in conserving the sacred groves. Of the three sacred groves, the one managed by individual family (Ollur Kavu) is highly disturbed as indicated by low stem density of mature trees (367 ha1) and poor regeneration potential with the ratio between mature trees and saplings is 1:0.4. In order to quantify the level of disturbance in these sacred groves, Ramakrishnan index of stand quality (RISQ) was calculated. The values obtained for all the three tree layers (i.e., mature trees, saplings and seedlings) in single family managed sacred grove (Ollur Kavu) was between 2.265 and 2.731, an indicator of the dominance of light demanding species in the population, suggested that the grove is highly disturbed one. Whereas, other two sacred groves are less disturbed as indicated by lower `RISQ' values (between 1.319 and 1.648). -

High Court of Judicature at Allahabad

HIGH COURT OF JUDICATURE AT ALLAHABAD NOTIFICATION DATED: ALLAHABAD: APRIL 08, 2013 No. 252 /DR(S)/2013 Sri Vijay Kumar Vishwakarma, Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Chitrakoot to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Sultanpur. No. 253 /DR(S)/2013 Sri Satyendra Prakash Pandey, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Deoria is appointed U/s 11(2) of the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973 (Act No. 2 of 1974) as Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Deorai vice Sri Abhishek Kumar Chaturvedi. No. 254 /DR(S)/2013 Sri Abhishek Kumar Chaturvedi, Judicial Magistrate, First Class, Deoria to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Varanasi. No. 255 /DR(S)/2013 Smt. Seema Verma, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Varanasi to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Bulandshahar. No. 256 /DR(S)/2013 Smt. Nisha Jha, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Bulandshahar to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Varanasi. No. 257 /DR(S)/2013 Sri Vikash Singh, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Varanasi to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Bahraich. No. 258 /DR(S)/2013 Sri Vineet Narain Pandey, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Bahraich to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Banda. No. 259 /DR(S)/2013 Km. Purnima Sagar, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Banda to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Pratapgarh. No. 260 /DR(S)/2013 Smt. Shagun Panwar, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Deoria to be Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Meerut. No. 261 /DR(S)/2013 Sri Yogesh Kumar-II, Additional Civil Judge, Junior Division, Deoria to be Civil Judge, Junior Division, Sardhana (Meerut) vice Sri Ramesh Chand-II. -

Rivers of Peace: Restructuring India Bangladesh Relations

C-306 Montana, Lokhandwala Complex, Andheri West Mumbai 400053, India E-mail: [email protected] Project Leaders: Sundeep Waslekar, Ilmas Futehally Project Coordinator: Anumita Raj Research Team: Sahiba Trivedi, Aneesha Kumar, Diana Philip, Esha Singh Creative Head: Preeti Rathi Motwani All rights are reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without prior permission from the publisher. Copyright © Strategic Foresight Group 2013 ISBN 978-81-88262-19-9 Design and production by MadderRed Printed at Mail Order Solutions India Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India PREFACE At the superficial level, relations between India and Bangladesh seem to be sailing through troubled waters. The failure to sign the Teesta River Agreement is apparently the most visible example of the failure of reason in the relations between the two countries. What is apparent is often not real. Behind the cacophony of critics, the Governments of the two countries have been working diligently to establish sound foundation for constructive relationship between the two countries. There is a positive momentum. There are also difficulties, but they are surmountable. The reason why the Teesta River Agreement has not been signed is that seasonal variations reduce the flow of the river to less than 1 BCM per month during the lean season. This creates difficulties for the mainly agrarian and poor population of the northern districts of West Bengal province in India and the north-western districts of Bangladesh. There is temptation to argue for maximum allocation of the water flow to secure access to water in the lean season. -

Okf"Kzd Izfrosnu Annual Report 2010-11

Annual Report 2010-11 Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya 1 bfUnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya okf"kZd izfrosnu Annual Report 2010-11 fo'o i;kZoj.k fnol ij lqJh lqtkrk egkik=k }kjk vksfM+lh u`R; dh izLrqfrA Presentation of Oddissi dance by Ms. Sujata Mahapatra on World Environment Day. 2 bfUnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; okf"kZd izfrosnu 2010&11 Annual Report 2010-11 Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya 3 lwph @ Index fo"k; i`"B dz- Contents Page No. lkekU; ifjp; 05 General Introduction okf"kZd izfrosnu 2010-11 Annual Report 2010-11 laxzgky; xfrfof/k;kWa 06 Museum Activities © bafnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky;] 'kkeyk fgYl] Hkksiky&462013 ¼e-iz-½ Hkkjr Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Shamla Hills, Bhopal-462013 (M.P.) India 1- v/kks lajpukRed fodkl % ¼laxzgky; ladqy dk fodkl½ 07 jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky; lfefr Infrastructure development: (Development of Museum Complex) ¼lkslk;Vh jftLVªs'ku ,DV XXI of 1860 ds varxZr iathd`r½ Exhibitions 07 ds fy, 1-1 izn'kZfu;kWa @ funs'kd] bafnjk xka/kh jk"Vªh; ekuo laxzgky;] 10 'kkeyk fgYl] Hkksiky }kjk izdkf'kr 1-2- vkdkZboy L=ksrksa esa vfHko`f) @ Strengthening of archival resources Published by Director, Indira Gandhi Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya, Shamla Hills, Bhopal for Rashtriya Manav Sangrahalaya Samiti (Registered under Society Registration Act XXI of 1860) 2- 'kS{kf.kd ,oa vkmVjhp xfrfof/k;kaW@ 11 fu%'kqYd forj.k ds fy, Education & Outreach Activities For Free Distribution 2-1 ^djks vkSj lh[kks* laxzgky; 'kS{kf.kd dk;Zdze @ -

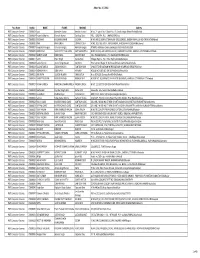

Roll Number of Eligible Candidates for the Post of Process Server(S). Examination Will Be Held on 23Rd February, 2014 at 02.00 P.M

Page 1 Roll Number of eligible Candidates for the post of Process Server(s). Examination will be held on 23rd February, 2014 at 02.00 P.M. to 03.30 P.M (MCQ) and thereafter written test will be conducted at 04.00 P.M. to 05.00 PM in the respective examination centre(s). List of examination centre(s) have already been uploaded on the website of HP High Court, separetely. Name of the Roll No. Fathers/Hus. Name & Correspondence Address Applicant 1 2 3 2001 Ravi Kumar S/O Prem Chand, V.P.O. Indpur Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 176401 S/O Bishan Dass, Vill Androoni Damtal P.O.Damtal Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2002 Parveen Kumar 176403 2003 Anish Thakur S/O Churu Ram, V.P.O. Baleer Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 2004 Ajay Kumar S/O Ishwar Dass, V.P.O. Damtal Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 S/O Yash Pal, Vill. Bain- Attarian P.O. Kandrori Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2005 Jatinder Kumar 176402 2006 Ankush Kumar S/O Dinesh Kumar, V.P.O. Bhapoo Tehsil Indora, Distt. Kangra-176401 2007 Ranjan S/O Buta Singh,Vill Bari P.O. Kandrori Tehsil Indora , Distt.Kangra-176402 2008 Sandeep Singh S/O Gandharv Singh, V.P.O. Rajakhasa Tehsil Indora, Distt. Kangra-176402 S/O Balwinder Singh, Vill Nadoun P.O. Chanour Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra- 2009 Sunder Singh 176401 2010 Jasvinder S/O Jaswant Singh,Vill Toki P.O. Chhanni Tehsil Indora, Distt.Kangra-176403 S/O Sh. Jarnail Singh, R/O Village Amran, Po Tipri, Tehsil Jaswan, Distt. -

Sacred Groves of India : an Annotated Bibliography

SACRED GROVES OF INDIA : AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Kailash C. Malhotra Yogesh Gokhale Ketaki Das [ LOGO OF INSA & DA] INDIAN NATIONAL SCIENCE ACADEMY AND DEVELOPMENT ALLIANCE Sacred Groves of India: An Annotated Bibliography Cover image: A sacred grove from Kerala. Photo: Dr. N. V. Nair © Development Alliance, New Delhi. M-170, Lower Ground Floor, Greater Kailash II, New Delhi – 110 048. Tel – 091-11-6235377 Fax – 091-11-6282373 Website: www.dev-alliance.com FOREWORD In recent years, the significance of sacred groves, patches of near natural vegetation dedicated to ancestral spirits/deities and preserved on the basis of religious beliefs, has assumed immense anthropological and ecological importance. The authors have done a commendable job in putting together 146 published works on sacred groves of India in the form of an annotated bibliography. This work, it is hoped, will be of use to policy makers, anthropologists, ecologists, Forest Departments and NGOs. This publication has been prepared on behalf of the National Committee for Scientific Committee on Problems of Environment (SCOPE). On behalf of the SCOPE National Committee, and the authors of this work, I express my sincere gratitude to the Indian National Science Academy, New Delhi and Development Alliance, New Delhi for publishing this bibliography on sacred groves. August, 2001 Kailash C. Malhotra, FASc, FNA Chairman, SCOPE National Committee PREFACE In recent years, the significance of sacred groves, patches of near natural vegetation dedicated to ancestral spirits/deities and preserved on the basis of religious beliefs, has assumed immense importance from the point of view of anthropological and ecological considerations. During the last three decades a number of studies have been conducted in different parts of the country and among diverse communities covering various dimensions, in particular cultural and ecological, of the sacred groves. -

CULTURE and BIODIVERSITY (Volume I)

CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY (Volume I) PREPARED UNDER THE NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY AND ACTION PLAN- INDIA Kailash C. Malhotra Coordinator 2003 Thematic Working Group on Culture and Biodiversity Mr. Feisal Alkazi Ms. Seema Bhatt (TPCG Member) Dr. Debal Deb Mr. Yogesh Gokhale Dr. Tiplut Nongbri Dr. D.N. Pandey Shri Shekhar Pathak Prof. Kailash C. Malhotra, Co-ordinator 2 (Kailash C.Malhotra, Coordinator, Thematic Group on Culture and Biodiversity (2003) . CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY. Prepared under National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, Executed by Ministry of Environment and Forests (Government of India), technical implementation by Technical and Policy Core Group coordinated by Kalpavriksh, and administrative coordination by Biotech Consortium India Ltd., funded by Global Environment Facility through United Nations Development Programm 178 pp.) 3 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 ABBREVIATIONS USED 11 1. INTRODUCTION 12 1.1 National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan - India 1.2 Thematic Working Group on Culture and Biodiversity 1.3 Objectives 1.4 Methodology 2. CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY 19 2.1 INTRODUCTION 2.2 The Conceptual Frame Work 2.2.1 Species Protection 2.2.2 Habitat Protection 2.2.3 Landscape Protection 3. POSITIVE – LINKS BETWEEN CULTURE AND BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY 21 4. THE ROLE OF RELIGIOUS ETHICS IN BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION IN INDIA 68 5. NEGATIVE – LINKS BETWEEN CULTURE AND BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY 77 6. WEAKENNING OF LINKS BETWEEN CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY 84 7. INITIATIVES TO REESTABLISH AND / OR STRENGTHEN POSITIVE LINKS BETWEEN CULTURE AND BIODIVERSITY 99 8. THE ROLE OF FOLK MUSIC AND DRAMA, ORAL LEGENDS AND PHOTOGRAPHY IN BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION 116 9. RECOMMENDATIONS 121 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 127 4 REFERENCES CITED 129 APPENDICES 137 I Composition of the Thematic Working Group on Culture and Biodiversity.137 II The modified Thematic Concept Note. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

To View the List of Candidates Who Applied Earlier Under Adv No. 2/2014

Advt. No. 2 / 2014 Post Name RegNo NAME FNAME MNAME Address PGT Computer Science 70000003 Jyoti Narender Kumar Neelam Kumari H.No. 21 Ward. No. 6 Barak No. 15 Gandhi Nagar RohtakRohtakRohtak PGT Computer Science 70000004 Priyanka Sharma Ramesh Kumar Sandhya Devi VILL. - DHUKRA, P.O. - JAMALSIRSASirsa PGT Computer Science 70000005 POONAM KRISHAN KUMAR SUSHILA H.NO-248/2, NEAR JOT RAM JAIN GIRLS SCHOOL, BABRA MOHALLA, ROHTAKROHTAKRohtak PGT Computer Science 70000006 AMIT MAN SINGH SOMVATI DEVI H.NO. 109, GALI NO. 4, VIKAS NAGAR, PHOOSGARH ROADKARNALKarnal PGT Computer Science 70000007 meenakshi kangra billu ram kangra kamlesh kangra #734/31 mahadev colony siwan gate kaithalkaithalKaithal PGT Computer Science 70000008 KIRTI RANA SHRI SATYA PAUL RANA SMT SHAKUNTLA RANA NIWAS, #23 SATSANG VIHAR , NEAR EKTA CHOWK, AMBALA CANTTAMBALAAmbala PGT Computer Science 70000010 MANJIT SINGH RAMNIWAS RAJPATI DEVI VILL NAURANGABAD P.O BAMLABHIWANIBhiwani PGT Computer Science 70000011 Sumit Prem Singh Sunita Devi Village- Baghru, P.O.- Tihar BaghruSonipatSonepat PGT Computer Science 70000012 Kavita Kumari Anand Singh Gusain Surji Devi Hno 3,Anand Nagar-'B',Boh road,Ambala CanttambalaAmbala PGT Computer Science 70000013 SALONI TANEJA ATAM PARKASH SANTOSH RANI 4 MILE STONE BAJEKAN MORE BAJEKAN HISAR ROAD SIRSASIRSASirsa PGT Computer Science 70000014 MONIKA NATH SOM NATH AVINASH HOUSE NO-1387 SECTOR-26PANCHKULAPanchkula PGT Computer Science 70000015 ANUPRIYA SURESH KUMAR SHAKUNTLA H.no 50-A/29, Chankya PuriROHTAKRohtak PGT Computer Science 70000016 SANDEEP KUMAR RAJINDER SINGH NIRMLA DEVI HOUSE NO. 38,SARSWATI VIHAR VPO SINGAWALA AMBALA CITYAMBALA CITYAmbala PGT Computer Science 70000017 RICHA KUKREJA RAMESH KUMAR KUKREJA PREM KUKREJA H.NO. 113 SECTOR 20 HUDA KAITHALKAITHALKaithal PGT Computer Science 70000018 Sneha Bahl Rajinder Singh Bahl Rama Bahl House No. -

THE HISTORIC BATTLE of DEORAI (AJMER) (12Th to 16Th March, 1659 AD)

Inspira- Journal of Modern Management & Entrepreneurship (JMME) 27 ISSN : 2231–167X, General Impact Factor : 2.3982, Volume 08, No. 01, January, 2018, pp. 27-29 THE MOST DECISIVE BATTLES OF MUGHAL HISTORY IN INDIA: THE HISTORIC BATTLE OF DEORAI (AJMER) (12th to 16th March, 1659 AD) Dr. Lata Agrawal Gopal Manoj ABSTRACT The transformation of warfare in South Asia during the foundation and consolidation of the Mughal Empire. The Mughals effectively combined the martial implements and practices of Europe, Central Asia and India into a model that was well suited for the unique demands and challenges of their setting. Ajmer with an importance, which added to its natural beauties, its superb situation, and its political distinction have placed it on a high pedestal amongst the cities of India. In this paper we have discussed about the Most Decisive Battles of Mughal History In India: The Historic Battle of Deorai, Ajmer- 12th To 16th March, 1659 AD. KEYWORDS: Transformation of Warfare, Mughal Empire, Political Distinction, Historic Battle, Mughal History. _______________ Introduction Emperor Akbar made Ajmer the head-quarters in 1561 AD for his operations in Rajputana and Gujrat. He made it a subha, making Jaipur, Jodhpur, Bikaner, Jaisalmer and Sirohi subordinate to it. According to the Ain-i-Akbari, the length of the Ajmer subah was 336 miles, and breadth 300 miles; and it was bounded by Agra.2 After illness of Shah Jahan in the year 1657 AD, a severe war of succession among his four sons Dara, Shuja, Aurangzeb and Murad started.3 Dara Shiokoh's three younger brothers, Shuja, Aurangzeb and Murad Baksh who were in Bengal, Deccan and Gujrat respectively, marched towards the capital, Agra, each claiming the throne.