Jjs/Y Ui Rizttdi&N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation

8/20/2019 Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation An advertisement for Lincoln Logs, 1925. Courtesy of Period Paper Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright AUGUST 23, 2018 BY MONICA M. SMITH Yes, this popular childhood toy was designed by none other than the son of architect Frank Lloyd Wright! Years ago while conducting research for the Lemelson Center’s Invention at Play exhibition, I was surprised to learn that Lincoln Logs—one of my favorite childhood toys—were designed by John Lloyd Wright, son of world-famous architect Frank Lloyd Wright. Overshadowed by his father, John has received little attention beyond a brief 1982 biography now available online. And he certainly seemed reticent about telling his own story, instead publicly sharing only a few experiences as part of his short, impressionistic 1946 book about Frank titled My Father Who Is On Earth. https://invention.si.edu/lincoln-logs-inventor-john-lloyd-wright 1/5 8/20/2019 Lincoln Logs Inventor John Lloyd Wright | Lemelson Center for the Study of Invention and Innovation Left: John Lloyd Wright in Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1921, ICHi-173783. Right: Frank Lloyd Wright with son John Lloyd Wright, undated., i73784. Courtesy of Chicago History Museum Turns out that John was both a successful toy designer and an architect in, dare I say it, his own right. Here is a brief overview of his story, including the origins of those ever-popular Lincoln Logs. Born in 1892, John Kenneth (later changed to Lloyd) Wright was the second of Frank and Catherine Wright’s six children. -

Reciprocal Sites Membership Program

2015–2016 Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Membership Program The Frank Lloyd Wright National Reciprocal Sites Program includes 30 historic sites across the United States. FLWR on your membership card indicates that you enjoy the National Reciprocal sites benefit. Benefits vary from site to site. Please check websites listed in this brochure for detailed information on each site. ALABAMA ARIZONA CALIFORNIA FLORIDA 1 Rosenbaum House 2 Taliesin West 3 Hollyhock House 4 Florida Southern College 601 RIVERVIEW DRIVE 12621 N. FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BLVD BARNSDALL PARK 750 FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT WAY FLORENCE, AL 35630 SCOTTSDALE, AZ 85261-4430 4800 HOLLYWOOD BLVD LAKELAND, FL 33801 256.718.5050 480.860.2700 LOS ANGELES, CA 90027 863.680.4597 ROSENBAUMHOUSE.COM FRANKLLOYDWRIGHT.ORG 323.644.6269 FLSOUTHERN.EDU/FLW WRIGHTINALABAMA.COM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION BARNSDALL.ORG FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: 9AM–4PM FOR UP-TO-DATE INFORMATION TOUR HOURS: TOUR HOURS: BOOKSHOP HOURS: 8:30AM–6PM TOUR HOURS: THURS–SUN, 11AM–4PM OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT OPEN ALL YEAR, EXCEPT TOUR TICKETS AVAILABLE AT THE THANKSGIVING, CHRISTMAS AND NEW Experience firsthand Frank Lloyd MAJOR HOLIDAYS. HOLLYHOCK HOUSE VISITOR’S CENTER YEAR’S DAY. 10AM–4PM Wright’s brilliant ability to integrate TUES–SAT, 10AM–4PM IN BARNSDALL PARK. VISITOR CENTER & GIFT SHOP HOURS: SUN, 1PM–4PM indoor and outdoor spaces at Taliesin Hollyhock House is Wright’s first 9:30AM–4:30PM West—Wright’s winter home, school The Rosenbaum House is the only Los Angeles project. Built between and studio from 1937-1959, located Discover the largest collection of Frank Lloyd Wright-designed 1919 and 1923, it represents his on 600 acres of dramatic desert. -

Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9

January 31 Auction: Baseball Autographs Signed 1950-55 Callahans 297 Honus Wagner 9 ............................ 500 Such a neat item, offered is a true high grade hand-signed 290 Fred Clarke 9.5 ......................... 100 Honus Wagner baseball card. So hard to find, we hardly ever Sharp card, this looks to be a fine Near Mint. Signed in par- see any kind of card signed by the legendary and beloved ticularly bold blue ink, this is a terrific autograph. Desirable Wagner. The offered card, slabbed by PSA/DNA, is well signed card, deadball era HOFer Fred Clarke died in 1960. centered with four sharp corners. Signed right in the center PSA/DNA slabbed. in blue fountain pen, this is a very nice signature. Key piece, this is another item that might appreciate rapidly in the 291 Clark Griffith 9 ............................ 150 future given current market conditions. Very scarce signed card, Clark Griffith died in 1955, giving him only a fairly short window to sign one of these. Sharp 298 Ed Walsh 9 ............................ 100 card is well centered and Near Mint or better to our eyes, Desirable signed card, this White Sox HOF pitcher from the this has a fine and clean blue ballpoint ink signature on the deadball era died in 1959. Signed neatly in blue ballpoint left side. PSA/DNA slabbed. ink in a good spot, this is a very nice signature. Slabbed Authentic by PSA/DNA, this is a quality signed card. 292 Rogers Hornsby 9.5 ......................... 300 Remarkable signed card, the card itself is Near Mint and 299 Lot of 3 w/Sisler 9 ..............................70 quite sharp, the autograph is almost stunningly nice. -

November 13, 2010 Prices Realized

SCP Auctions Prices Realized - November 13, 2010 Internet Auction www.scpauctions.com | +1 800 350.2273 Lot # Lot Title 1 C.1910 REACH TIN LITHO BASEBALL ADVERTISING DISPLAY SIGN $7,788 2 C.1910-20 ORIGINAL ARTWORK FOR FATIMA CIGARETTES ROUND ADVERTISING SIGN $317 3 1912 WORLD CHAMPION BOSTON RED SOX PHOTOGRAPHIC DISPLAY PIECE $1,050 4 1914 "TUXEDO TOBACCO" ADVERTISING POSTER FEATURING IMAGES OF MATHEWSON, LAJOIE, TINKER AND MCGRAW $288 5 1928 "CHAMPIONS OF AL SMITH" CAMPAIGN POSTER FEATURING BABE RUTH $2,339 6 SET OF (5) LUCKY STRIKE TROLLEY CARD ADVERTISING SIGNS INCLUDING LAZZERI, GROVE, HEILMANN AND THE WANER BROTHERS $5,800 7 EXTREMELY RARE 1928 HARRY HEILMANN LUCKY STRIKE CIGARETTES LARGE ADVERTISING BANNER $18,368 8 1930'S DIZZY DEAN ADVERTISING POSTER FOR "SATURDAY'S DAILY NEWS" $240 9 1930'S DUCKY MEDWICK "GRANGER PIPE TOBACCO" ADVERTISING SIGN $178 10 1930S D&M "OLD RELIABLE" BASEBALL GLOVE ADVERTISEMENTS (3) INCLUDING COLLINS, CRITZ AND FONSECA $1,090 11 1930'S REACH BASEBALL EQUIPMENT DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $425 12 BILL TERRY COUNTERTOP AD DISPLAY FOR TWENTY GRAND CIGARETTES SIGNED "TO BARRY" - EX-HALPER $290 13 1933 GOUDEY SPORT KINGS GUM AND BIG LEAGUE GUM PROMOTIONAL STORE DISPLAY $1,199 14 1933 GOUDEY WINDOW ADVERTISING SIGN WITH BABE RUTH $3,510 15 COMPREHENSIVE 1933 TATTOO ORBIT DISPLAY INCLUDING ORIGINAL ADVERTISING, PIN, WRAPPER AND MORE $1,320 16 C.1934 DIZZY AND DAFFY DEAN BEECH-NUT ADVERTISING POSTER $2,836 17 DIZZY DEAN 1930'S "GRAPE NUTS" DIE-CUT ADVERTISING DISPLAY $1,024 18 PAIR OF 1934 BABE RUTH QUAKER -

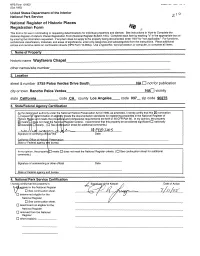

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 \M/IVIUJ i ^vy. (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________________ historic name Wayfarers Chapel ________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location ___________________________ street & number 5755 Palos Verdes Drive South_______ NA d not for publication city or town Rancho Palos Verdes________________ NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Los Angeles. code 037_ zip code 90275 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination D request f fr*d; (termination -

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist

1955 Bowman Baseball Checklist 1 Hoyt Wilhelm 2 Alvin Dark 3 Joe Coleman 4 Eddie Waitkus 5 Jim Robertson 6 Pete Suder 7 Gene Baker 8 Warren Hacker 9 Gil McDougald 10 Phil Rizzuto 11 Bill Bruton 12 Andy Pafko 13 Clyde Vollmer 14 Gus Keriazakos 15 Frank Sullivan 16 Jimmy Piersall 17 Del Ennis 18 Stan Lopata 19 Bobby Avila 20 Al Smith 21 Don Hoak 22 Roy Campanella 23 Al Kaline 24 Al Aber 25 Minnie Minoso 26 Virgil Trucks 27 Preston Ward 28 Dick Cole 29 Red Schoendienst 30 Bill Sarni 31 Johnny TemRookie Card 32 Wally Post 33 Nellie Fox 34 Clint Courtney 35 Bill Tuttle 36 Wayne Belardi 37 Pee Wee Reese 38 Early Wynn 39 Bob Darnell 40 Vic Wertz 41 Mel Clark 42 Bob Greenwood 43 Bob Buhl Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 44 Danny O'Connell 45 Tom Umphlett 46 Mickey Vernon 47 Sammy White 48 (a) Milt BollingFrank Bolling on Back 48 (b) Milt BollingMilt Bolling on Back 49 Jim Greengrass 50 Hobie Landrith 51 El Tappe Elvin Tappe on Card 52 Hal Rice 53 Alex Kellner 54 Don Bollweg 55 Cal Abrams 56 Billy Cox 57 Bob Friend 58 Frank Thomas 59 Whitey Ford 60 Enos Slaughter 61 Paul LaPalme 62 Royce Lint 63 Irv Noren 64 Curt Simmons 65 Don ZimmeRookie Card 66 George Shuba 67 Don Larsen 68 Elston HowRookie Card 69 Billy Hunter 70 Lew Burdette 71 Dave Jolly 72 Chet Nichols 73 Eddie Yost 74 Jerry Snyder 75 Brooks LawRookie Card 76 Tom Poholsky 77 Jim McDonald 78 Gil Coan 79 Willy MiranWillie Miranda on Card 80 Lou Limmer 81 Bobby Morgan 82 Lee Walls 83 Max Surkont 84 George Freese 85 Cass Michaels 86 Ted Gray 87 Randy Jackson 88 Steve Bilko 89 Lou -

1962 Topps Baseball "Bucks" Set Checklist

1962 TOPPS BASEBALL "BUCKS" SET CHECKLIST NNO Hank Aaron NNO Joe Adcock NNO George Altman NNO Jim Archer NNO Richie Ashburn NNO Ernie Banks NNO Earl Battey NNO Gus Bell NNO Yogi Berra NNO Ken Boyer NNO Jackie Brandt NNO Jim Bunning NNO Lou Burdette NNO Don Cardwell NNO Norm Cash NNO Orlando Cepeda NNO Bob Clemente NNO Rocky Colavito NNO Chuck Cottier NNO Roger Craig NNO Bennie Daniels NNO Don Demeter NNO Don Drysdale NNO Chuck Estrada NNO Dick Farrell NNO Whitey Ford NNO Nellie Fox NNO Tito Francona NNO Bob Friend NNO Jim Gentile NNO Dick Gernert NNO Lenny Green NNO Dick Groat NNO Woodie Held NNO Don Hoak NNO Gil Hodges NNO Elston Howard NNO Frank Howard NNO Dick Howser NNO Ken L. Hunt NNO Larry Jackson NNO Joe Jay Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 NNO Al Kaline NNO Harmon Killebrew NNO Sandy Koufax NNO Harvey Kuenn NNO Jim Landis NNO Norm Larker NNO Frank Lary NNO Jerry Lumpe NNO Art Mahaffey NNO Frank Malzone NNO Felix Mantilla NNO Mickey Mantle NNO Roger Maris NNO Eddie Mathews NNO Willie Mays NNO Ken McBride NNO Mike McCormick NNO Stu Miller NNO Minnie Minoso NNO Wally Moon NNO Stan Musial NNO Danny O'Connell NNO Jim O'Toole NNO Camilo Pascual NNO Jim Perry NNO Jim Piersall NNO Vada Pinson NNO Juan Pizarro NNO Johnny Podres NNO Vic Power NNO Bob Purkey NNO Pedro Ramos NNO Brooks Robinson NNO Floyd Robinson NNO Frank Robinson NNO Johnny Romano NNO Pete Runnels NNO Don Schwall Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 2. -

MEDIA and LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS of LATINOS in BASEBALL and BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of T

MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION by MIHIR D. PAREKH Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2015 Copyright © by Mihir Parekh 2015 All Rights Reserved ii Acknowledgements I would like to express my thanks to my supervisor, Dr. William Arcé, whose knowledge and expertise in Latino studies were vital to this project. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Timothy Morris and Dr. James Warren, for the assistance they provided at all levels of this undertaking. Their wealth of knowledge in the realm of sport literature was invaluable. To my family: the gratitude I have for what you all have provided me cannot be expressed on this page alone. Without your love, encouragement, and support, I would not be where I am today. Thank you for all you have sacrificed for me. April 22, 2015 iii Abstract MEDIA AND LITERARY REPRESENTATIONS OF LATINOS IN BASEBALL AND BASEBALL FICTION Mihir D. Parekh, MA The University of Texas at Arlington, 2015 Supervising Professors: William Arcé, Timothy Morris, James Warren The first chapter of this project looks at media representations of two Mexican- born baseball players—Fernando Valenzuela and Teodoro “Teddy” Higuera—pitchers who made their big league debuts in the 1980s and garnered significant attention due to their stellar play and ethnic backgrounds. Chapter one looks at U.S. media narratives of these Mexican baseball players and their focus on these foreign athletes’ bodies when presenting them the American public, arguing that 1980s U.S. -

A Rather Humble Beginning

A Rather Humble Beginning The popular cereal flake in the orange box was born association began with a sign on the left field wall at old when a Minneapolis health clinician accidentally spilled Nicollet Park in south Minneapolis in 1933. General Mills’ some wheat bran mixture on a hot stove, creating tasty broadcast deal with the minor league Minneapolis wheat flakes. The idea for whole-grain cereal flakes was Millers on radio station WCCO included the large brought to the attention of the head miller at the signboard that Wheaties would use to introduce its new Washburn Crosby Company (General Mills’ predecessor), advertising slogan. The late Knox Reeves (of the George Cormack, who perfected the process for Minneapolis-based advertising agency that bore his producing the flakes. In November 1924, the ready-to-eat name) was asked what should be printed on the cereal known as Washburn’s Gold Medal Whole Wheat signboard for his client. He took out a pad and pencil, it is Flakes during its development was ready for the market. said, sketched a Wheaties package, thought for a minute, The cumbersome name was shortened to “Wheaties” as and then printed “Wheaties - The Breakfast of Champions.” the result of an employee contest won by Jane From that modest beginning, Wheaties’ storied sports Bausman, the wife of a company executive. Wheaties’ heritage has gone on to embrace many of the greatest first venture into the world of sports was the sponsorship athletes of all time. of minor league baseball broadcasts. The brand’s sports wheaties.com WHEATIES HISTORY 1 © 2010 General Mills, Inc. -

Bats 3 Post-Expansion

BATS 3 POST-EXPANSION (1961-to the present) 30 teams 31 players per team 930 total players Names in red are Hall of Famers MVP Most Valuable Player league award ROY Rookie of the Year; league award. CY Cy Young winner league award; CY(M) Cy Young winner when only awarded to best pitcher in the majors NATIONAL LEAGUE MILWAUKEE-ATLANTA BRAVES ARIZONA DIAMONDBACKS CHICAGO CUBS CINCINNATI REDS Hank Aaron – 1971 Jay Bell – 1999 Javier Baez – 2017 Johnny Bench – 1970 MVP Felipe Alou – 1966 Eric Byrnes – 2007 Ernie Banks – 1961 Leo Cardenas – 1966 Jeff Blauser – 1997 Alex Cintron – 2003 Michael Barrett – 2006 Sean Casey – 1999 Rico Carty – 1970 Craig Counsell – 2002 Glenn Beckert – 1971 Dave Concepcion – 1978 Del Crandall – 1962 Stephen Drew – 2008 Kris Bryant – 2016 MVP Eric Davis – 1987 Darrell Evans – 1973 Steve Finley – 2000 Jody Davis – 1983 Adam Dunn – 2004 Freddie Freeman – 2017 Paul Goldschmidt – 2015 Andre Dawson – 1987 MVP George Foster – 1977 MVP Rafael Furcal – 2003 Luis Gonzalez – 2001 Shawon Dunston – 1995 Ken Griffey, Sr. - 1976 Ralph Garr – 1974 Orlando Hudson – 2008 Leon Durham – 1982 Barry Larkin – 1996 Andruw Jones – 2005 Conor Jackson – 2006 Mark Grace – 1995 Lee May – 1969 Chipper Jones – 2008 Jake Lamb – 2016 Jim Hickman – 1970 Devin Mesoraco – 2014 David Justice – 1994 Damian Miller – 2001 Dave Kingman – 1979 Joe Morgan – 1976 MVP Javier Lopez – 2003 Miguel Montero – 2009 Derrek Lee – 2005 Tony Perez – 1970 Brian McCann – 2006 David Peralta – 2015 Anthony Rizzo – 2016 Brandon Phillips – 2007 Fred McGriff – 1994 A.J. Pollock -

J This Week Two Sections 20 Pages COVERING Arne

UONliOUTH JO. HISTORICAL. ASS!| . , f a s s a o u ) . »HV.f.. J ■ X This Week COVERING / TOVVNSHIPB OF Two Sections HOLMDEL, MADISON MARLBORO, MATAWAN AND 20 Pages MATAWAN BOROUGH Member Member 90th YEAR — 15th WEEK National Editorial Association MATAWAN, N. J., THURSDAY, OCTOBER 9, 1958 New Jeney Preu Asiodition Single Copy Ten CenU Arne Kalma Test Cleanup Day Salary Ordinance Something Has Been Added At MHS Football Field Sawmill In Residential Zone On MatawanCoancUwoman Mrs. Genevieve Donnell announced Semi-Finalist Tuesday that the semt-a a n u a 1 Gains Adoption Middlesex Rd. Finally Rejected ‘,Cieanup OayJHa Matawan wtH 10,000 Highest To be held ThursdayrOctn«r“ An Township Sets Madison Township Committee Rules Out Compete Once Again residents of the borough are urg Date For Vote Recommendation For Zoning Variance i ed to co-operate .by making a Principal Luther Foster of Mata general cleanup campaign in An ordinance establishing a max Nn sawmill will be located and wan High School announced that their cellars and attics. imum range of salaries for mem Miss Joan Visits operated on the lands of Frederick Arne Kalma, a senior student, has Cleanup day presents an oppor nnd Wllllnm Formnn, Middlesex been named a semi-finalist in the tunity (or borough residents to bers of the police department, rep Nearly 1000 youngsters nnd Rd. Mnyor Jolm L. Clinmborlaln 1958-59 National Merit Scholarship dear out trash and refuse which resenting an Increase of $700 per adults overflowed the J. J. New nniiounccd thnt the township com- competition. will be carted away by the gar man, was introduced yesterday by berry Co., storo, West Front St., inlttec Monday wns awuro tlie run- As a Kemi-finalist. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

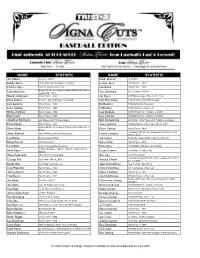

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank