Introduction: the Man Who Had Three Lives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Russian Faculty Research and Scholarship Russian 2009 Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs Custom Citation Harte, Tim. "Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports," Nabokov Studies 12.1 (2009): 147-166. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/russian_pubs/1 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tim Harte Bryn Mawr College Dec. 2012 Athletic Inspiration: Vladimir Nabokov and the Aesthetic Thrill of Sports “People have played for as long as they have existed,” Vladimir Nabokov remarked in 1925. “During certain eras—holidays for humanity—people have taken a particular fancy to games. As it was in ancient Greece and ancient Rome, so it is in our present-day Europe” (“Braitenshtreter – Paolino,” 749). 1 For Nabokov, foremost among these popular games were sports competitions. An ardent athlete and avid sports fan, Nabokov delighted in the competitive spirit of athletics and creatively explored their aesthetic as well as philosophical ramifications through his poetry and prose. As an essential, yet underappreciated component of the Russian-American writer’s art, sports appeared first in early verse by Nabokov before subsequently providing a recurring theme in his fiction. The literary and the athletic, although seemingly incongruous modes of human activity, frequently intersected for Nabokov, who celebrated the thrills, vigor, and beauty of sports in his present-day “holiday for humanity” with a joyous energy befitting such physical activity. -

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read

The 200 Plays That Every Theatre Major Should Read Aeschylus The Persians (472 BC) McCullers A Member of the Wedding The Orestia (458 BC) (1946) Prometheus Bound (456 BC) Miller Death of a Salesman (1949) Sophocles Antigone (442 BC) The Crucible (1953) Oedipus Rex (426 BC) A View From the Bridge (1955) Oedipus at Colonus (406 BC) The Price (1968) Euripdes Medea (431 BC) Ionesco The Bald Soprano (1950) Electra (417 BC) Rhinoceros (1960) The Trojan Women (415 BC) Inge Picnic (1953) The Bacchae (408 BC) Bus Stop (1955) Aristophanes The Birds (414 BC) Beckett Waiting for Godot (1953) Lysistrata (412 BC) Endgame (1957) The Frogs (405 BC) Osborne Look Back in Anger (1956) Plautus The Twin Menaechmi (195 BC) Frings Look Homeward Angel (1957) Terence The Brothers (160 BC) Pinter The Birthday Party (1958) Anonymous The Wakefield Creation The Homecoming (1965) (1350-1450) Hansberry A Raisin in the Sun (1959) Anonymous The Second Shepherd’s Play Weiss Marat/Sade (1959) (1350- 1450) Albee Zoo Story (1960 ) Anonymous Everyman (1500) Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf Machiavelli The Mandrake (1520) (1962) Udall Ralph Roister Doister Three Tall Women (1994) (1550-1553) Bolt A Man for All Seasons (1960) Stevenson Gammer Gurton’s Needle Orton What the Butler Saw (1969) (1552-1563) Marcus The Killing of Sister George Kyd The Spanish Tragedy (1586) (1965) Shakespeare Entire Collection of Plays Simon The Odd Couple (1965) Marlowe Dr. Faustus (1588) Brighton Beach Memoirs (1984 Jonson Volpone (1606) Biloxi Blues (1985) The Alchemist (1610) Broadway Bound (1986) -

Chronology of Lolita

Chronology of Lolita CHRONOLOGY OF LOLITA This chronology is based on information gathered from the text of Nabokov’s Lolita as well as from the chronological reconstructions prepared by Carl Proffer in his Keys to Lolita and Dieter Zimmer’s online chronology at <http://www.d-e-zimmer.de/LolitaUSA/LoChrono.htm> (last accessed on No- vember 13, 2008). For a discussion of the problems of chronology in the novel, see Zimmer’s site. The page numbers in parenthesis refer to passages in the text where the information on chronology can be found. 1910 Humbert Humbert born in Paris, France (9) 1911 Clare Quilty born in Ocean City, Maryland (31) 1913 Humbert’s mother dies from a lightning strike (10) 1923 Summer: Humbert and Annabel Leigh have romance (11) Autumn: Humbert attends lycée in Lyon (11) December (?): Annabel dies in Corfu (13) 1934 Charlotte Becker and Harold E. Haze honeymoon in Veracruz, Mexico; Dolores Haze conceived on this trip (57, 100) 1935 January 1: Dolores Haze born in Pisky, a town in the Midwest (65, 46) April: Humbert has brief relationship with Monique, a Parisian prostitute (23) Humbert marries Valeria Zborovski (25, 30) 1937 Dolly’s brother born (68) 1939 Dolly’s brother dies (68) Humbert receives inheritance from relative in America (27) Valeria discloses to Humbert that she is having an affair; divorce proceedings ensue (27, 32) xv Chronology of Lolita 1940 Winter: Humbert spends winter in Portugal (32) Spring: Humbert arrives in United States and takes up job devising and editing perfume ads (32) Over next two years -

Pedophilia, Poe, and Postmodernism in Lolita

Nabokov’s Dark American Dream: Pedophilia, Poe, and Postmodernism in Lolita by Heather Menzies Jones A Thesis Submitted to the Department of English of the State University of New York, College at Brockport, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS 1995 ii Nabokov’s Dark American Dream: Pedophilia, Poe, and Postmodernism in Lolita by Heather Menzies Jones APPROVED: ________________________________________ _________ Advisor Date ________________________________________ _________ Reader ________________________________________ __________ Reader ________________________________________ __________ Chair, Graduate Committee _______________________________________ ___________ Chair, Department of English iii Table of Contents Chapter Page Introduction 1 Pedophilia and Lolita 10 Poe and Lolita 38 Postmodernism and Lolita 58 Works Cited 83 1 INTRODUCTION The following thesis about Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita first began as a paper written as an assignment for a course about postmodern American literature. In the initial paper's title there was an allusion made to the implicated reader, and the paper itself was about giving Lolita a newer and postmodern reading. To read Lolita again, years after doing so initially, was a distinctly disturbing thing to do. The cultural climate has certainly changed since the mid-1950's when the book was first published in this country, and this alone makes the rereading of this novel an engaging opportunity. Lionel Trilling wrote that Nabokov sought to shock us and that he had to stage-manage something uniquely different in order to do so. Trilling believed that the effect of breaking the taboo "about the sexual unavailability of very young girls" had the same force as a "wife's infidelity had for Shakespeare" (5). -

A Delicate Balance

PEEK BEHIND THE SCENES OF A DELICATE BALANCE Compiled By Lotta Löfgren To Our Patrons Most of us who attend a theatrical performance know little about how a play is actually born to the stage. We only sit in our seats and admire the magic of theater. But the birthing process involves a long period of gestation. Certainly magic does happen on the stage, minute to minute, and night after night. But the magic that theatergoers experience when they see a play is made possible only because of many weeks of work and the remarkable dedication of many, many volunteers in order to transform the text into performance, to move from page to stage. In this study guide, we want to give you some idea of what goes into creating a show. You will see the actors work their magic in the performance tonight. But they could not do their job without the work of others. Inside you will find comments from the director, the assistant director, the producer, the stage manager, the set -

6 X 10.5 Long Title.P65

Cambridge University Press 0521542332 - The Cambridge Companion to Edward Albee Edited by Stephen Bottoms Table of Contents More information CONTENTS List of illustrations page ix Notes on contributors xi Acknowledgments xv Notes on the text xvi Chronology xvii 1 Introduction: The man who had three lives 1 stephen bottoms 2 Albee’s early one-act plays: “A new American playwright from whom much is to be expected” 16 philip c. kolin 3 Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?: Toward the marrow 39 matthew roudane´ 4 “Withered age and stale custom”: Marriage, diminution, and sex in Tiny Alice, A Delicate Balance, and Finding the Sun 59 john m. clum 1 5 Albee’s 3 /2: The Pulitzer plays 75 thomas p. adler 6 Albee’s threnodies: Box-Mao-Box, All Over, The Lady from Dubuque, and Three Tall Women 91 brenda murphy 7 Minding the play: Thought and feeling in Albee’s “hermetic” works 108 gerry mccarthy vii © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521542332 - The Cambridge Companion to Edward Albee Edited by Stephen Bottoms Table of Contents More information contents 8 Albee’s monster children: Adaptations and confrontations 127 stephen bottoms 9 “Better alert than numb”: Albee since the eighties 148 christopher bigsby 10 Albee stages Marriage Play: Cascading action, audience taste, and dramatic paradox 164 rakesh h. solomon 11 “Playing the cloud circuit”: Albee’s vaudeville show 178 linda ben-zvi 12 Albee’s The Goat: Rethinking tragedy for the 21st century 199 j. ellen gainor 13 “Words; words...They’re such a pleasure.” (An Afterword) 217 ruby cohn 14 Borrowed time: An interview with Edward Albee 231 stephen bottoms Notes on further reading 251 Select bibliography 253 Index 259 viii © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org. -

Past Productions

Past Productions 2017-18 2012-2013 2008-2009 A Doll’s House Born Yesterday The History Boys Robert Frost: This Verse Sleuth Deathtrap Business Peter Pan Les Misérables Disney’s The Little The Importance of Being The Year of Magical Mermaid Earnest Thinking Only Yesterday Race Laughter on the 23rd Disgraced No Sex Please, We're Floor Noises Off British The Glass Menagerie Nunsense Take Two 2016-17 Macbeth 2011-2012 2007-2008 A Christmas Carol Romeo and Juliet How the Other Half Trick or Treat Boeing-Boeing Loves Red Hot Lovers Annie Doubt Grounded Les Liaisons Beauty & the Beast Mamma Mia! Dangereuses The Price M. Butterfly Driving Miss Daisy 2015-16 Red The Elephant Man Our Town Chicago The Full Monty Mary Poppins Mad Love 2010-2011 2006-2007 Hound of the Amadeus Moon Over Buffalo Baskervilles The 39 Steps I Am My Own Wife The Mountaintop The Wizard of Oz Cats Living Together The Search for Signs of Dancing At Lughnasa Intelligent Life in the The Crucible 2014-15 Universe A Chorus Line A Christmas Carol The Real Thing Mid-Life! The Crisis Blithe Spirit The Rainmaker Musical Clybourne Park Evita Into the Woods 2005-2006 Orwell In America 2009-2010 Lend Me A Tenor Songs for a New World Hamlet A Number Parallel Lives Guys And Dolls 2013-14 The 25th Annual I Love You, You're Twelve Angry Men Putnam County Perfect, Now Change God of Carnage Spelling Bee The Lion in Winter White Christmas I Hate Hamlet Of Mice and Men Fox on the Fairway Damascus Cabaret Good People A Walk in the Woods Spitfire Grill Greater Tuna Past Productions 2004-2005 2000-2001 -

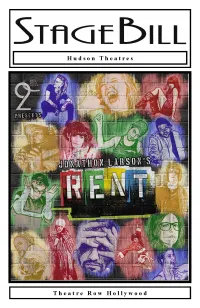

RENT Program

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ Remember the first time you were inspired by a performance? The first time that your eyes opened just a little bit wider to try to capture and record everything you were seeing? Maybe it was your first Broadway show, or the first film that really grabbed you. Maybe it was as simple as a third-grade performance. It’s hard to forget that initial sense of wonder and sudden realization that the world might just contain magic . This is the sort of experience the 2Cents Theatre Group is trying to create. Classic performances are hard to define, but easy to spot. Our Goal is to pay homage and respect to the classics, while simultaneously adding our own unique 2 Cents to create a free-standing performance piece that will bemuse, inform, and inspire. 2¢ Theatre Group is in residence at the Hudson Theatre, at 6539 Santa Monica Boulevard. You can catch various talented members of the 2 Cent Crew in our Monthly Cabaret at the Hudson Theatre Café . the second Sunday of each Month. also from 2Cents AT THE HUDSON… TICKETS ON SALE NOW! May 30 - June 30 EACH WEEK FEATURING LIVE PRE-SHOW MUSIC BY: Thurs 5/30 - Stage 11 Sun 6/2 - Anderson William Thurs 6/6 - 30 North SuN 6/9 - Kelli Debbs Thurs 6/13 - TBD Sun 6/16 - Lee Wahlert Thurs 6/20 - TBD Sun 6/23 - TBD Thurs 6/27 - Fire Chief Charlie Sun 6/30 - Chris Duquee Cody Lyman Kristen Boulé & 2Cents Theatre Board of Directors with Michael Abramson at the Hudson Theatres present Book, Music & Lyrics by Jonathan Larson Dedrick Bonner Kate Bowman Amber Bracken Ariel Jean Brooker Brian -

Robert A. Wilson Collection Related to James Purdy

Special Collections Department Robert A. Wilson Collection related to James Purdy 1956 - 1998 Manuscript Collection Number: 369 Accessioned: Purchase and gifts, April 1998-2009 Extent: .8 linear feet Content: Letters, cards, photographs, typescripts, galleys, reviews, newspaper clippings, publishers' announcements, publicity and ephemera Access: The collection is open for research. Processed: June 1998, by Meghan J. Fuller for reference assistance email Special Collections or contact: Special Collections, University of Delaware Library Newark, Delaware 19717-5267 (302) 831-2229 Table of Contents Biographical Notes Scope and Contents Note Series Outline Contents List Biographical Notes James Purdy Born in Ohio on July 17, 1923, James Purdy is one of the United States' most prolific, yet little known writers. A novelist, poet, playwright and amateur artist, Purdy has published over fifty volumes. He received his education at the University of Chicago and the University of Peubla in Mexico. In addition to writing, Purdy also has served as an interpreter in Latin America, France, and Spain, and spent a year lecturing in Europe with the United States Information Agency (1982). From the outset of his writing career, Purdy has had difficulties attracting the attention of both publishers and critics. His first several short stories were rejected by every magazine to which he sent them, and he was forced to sign with a private publisher for his first two books, 63: Dream Palace and Don't Call Me by My Right Name and Other Stories, both published in 1956. Hoping to increase his readership, Purdy sent copies of these first two books to writers he admired, including English poet Dame Edith Sitwell. -

The Teacher and American Literature. Papers Presented at the 1964 Convention of the National Council of Teachers of English

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 042 741 TB 001 605 AUTHOR Leary, Lewis, Fd. TITLE The Teacher and American Literature. Papers Presented at the 1964 Convention of the National Council of Teachers of English. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Champaign, Ill. PUB DATE 65 NOTE 194p. EDITS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.75 HC-$9.80 DESCRIPTORS American Culture, *American Literature, Authors, Biographies, Childrens Books, Elementary School Curriculum, Literary Analysis, *Literary Criticism, *Literature Programs, Novels, Poetry, Short Stories ABSTRACT Eighteen papers on recent scholarship and its implications for school programs treat American ideas, novels, short stories, poetry, Emerson and Thoreau, Hawthorne and Melville, Whitman and Dickinson, Twain and Henry James, and Faulkner and Hemingway. Authors are Edwin H. Cady, Edward J. Gordon, William Peden, Paul H. Krueger, Bernard Duffey, John A. Myers, Jr., Theodore Hornberger, J. N. Hook, Walter Harding, Betty Harrelson Porter, Arlin Turner, Robert E. Shafer, Edmund Reiss, Sister M. Judine, Howard W.Webb, Jr., Frank H. Townsend, Richard P. Adams, and John N. Terrey. In five additional papers, Willard Thorp and Alfred H. Grommon discuss the relationship of the teacher and curriculum to new.a7proaches in American literature, while Dora V. Smith, Ruth A. French, and Charlemae Rollins deal with the implications of American literature for elementary school programs and for children's reading. (MF) U.S. DEPAIIMENT Of NE11114. EDUCATION A WOK Off ICE Of EDUCATION r--1 THIS DOCUMENT HAS KM ITEPtODUCIO EXACTLY AS IHCEIVID 1110D1 THE 11115011 01 014111I1.1101 01,611111116 IL POINTS Of TIM PI OPINIONS 4" SIAM 00 NOT IKESSAIllY INPINSENT OFFICIAL OW Of IDS/CATION N. -

Derek Jarman Sebastiane

©Jack Fritscher, Ph.D. Pre-Publication Web Posting 191 DEREK JARMAN SEBASTIANE Derek Jarman, the British painter and set designer and filmmaker and diarist, said about the Titanic 1970s, before the iceberg of AIDS: “It’s no wonder that a generation in reaction [to homopho- bia before Stonewall] should generate an orgy [the 1970s] which came as an antidote to repression.” Derek knew decadence. And its cause. He was a gay saint rightly canonized, literally, by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence. As editor of Drummer, I featured his work to honor his talent. If only, like his rival Robert Mapplethorpe, he had shot a Drummer cover as did director Fred Halsted whose S&M films LA Plays Itself and Sex Garage are in the Museum of Modern Art. One problem: in the 1970s, England was farther away than it is now, and Drummer was lucky to get five photographs from Sebastiane. On May 1, 1969, I had flown to London on a prop-jet that had three seats on each side of its one aisle. A week later the first jumbo jet rolled out at LAX. That spring, all of Europe was reel- ing still from the student rebellions of the Prague Summer of 1968. London was Carnaby Street, The Beatles, and on May 16, the fabulous Brit gangsters the Kray twins—one of whom was gay—were sentenced. London was wild. I was a sex tourist who spent my first night in London on the back of leatherman John Howe’s motorcycle, flying past Big Ben as midnight chimed. -

Edward Albee's at Home at The

CAST OF CHARACTERS TROY KOTSUR*............................................................................................................................PETER Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director RUSSELL HARVARD*, TYRONE GIORDANO..........................................................................................JERRY AND AMBER ZION*.................................................................................................................................ANN JAKE EBERLE*...............................................................................................................VOICE OF PETER JEFF ALAN-LEE*..............................................................................................................VOICE OF JERRY PAIGE LINDSEY WHITE*........................................................................................................VOICE OF ANN *Indicates a member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of David J. Kurs Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Artistic Director Production of ACT ONE: HOMELIFE ACT TWO: THE ZOO STORY Peter and Ann’s living room; Central Park, New York City. EDWARD ALBEE’S New York City, East Side, Seventies. Sunday. Later that same day. AT HOME AT THE ZOO ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION STAFF STARRING COSTUME AND PROPERTIES REHEARSAL STAGE Jeff Alan-Lee, Jack Eberle, Tyrone Giordano, Russell Harvard, Troy Kotsur, WARDROBE SUPERVISOR SUPERVISOR INTERPRETER COMBAT Paige Lindsey White, Amber Zion Deborah Hartwell Courtney Dusenberry Alek Lev