Century Britain: the Lived Experience of Yoga Practitioners

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I on an Empty Stomach After Evacuating the Bladder and Bowels

• I on a Tllt' Bi11lr· ol' \lodt•nJ Yoga-It� Philo�opl1� and Prad il't' -hv thr: World" s Fon-·mo �l 'l'r·ar·lwr B • I< . S . IYENGAR \\ it h compldc· dt·!wription� and illustrations of all tlw po �tun·� and bn·athing techniqn··� With More than 600 Photographs Positioned Next to the Exercises "For the serious student of Hatha Yoga, this is as comprehensive a handbook as money can buy." -ATLANTA JOURNAL-CONSTITUTION "The publishers calls this 'the fullest, most practical, and most profusely illustrated book on Yoga ... in English'; it is just that." -CHOICE "This is the best book on Yoga. The introduction to Yoga philosophy alone is worth the price of the book. Anyone wishing to know the techniques of Yoga from a master should study this book." -AST RAL PROJECTION "600 pictures and an incredible amount of detailed descriptive text as well as philosophy .... Fully revised and photographs illustrating the exercises appear right next to the descriptions (in the earlier edition the photographs were appended). We highly recommend this book." -WELLNESS LIGHT ON YOGA § 50 Years of Publishing 1945-1995 Yoga Dipika B. K. S. IYENGAR Foreword by Yehudi Menuhin REVISED EDITION Schocken Books New 1:'0rk First published by Schocken Books 1966 Revised edition published by Schocken Books 1977 Paperback revised edition published by Schocken Books 1979 Copyright© 1966, 1968, 1976 by George Allen & Unwin (Publishers) Ltd. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

SWAMI YOGANANDA and the SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP a Successful Hindu Countermission to the West

STATEMENT DS213 SWAMI YOGANANDA AND THE SELF-REALIZATION FELLOWSHIP A Successful Hindu Countermission to the West by Elliot Miller The earliest Hindu missionaries to the West were arguably the most impressive. In 1893 Swami Vivekananda (1863 –1902), a young disciple of the celebrated Hindu “avatar” (manifestation of God) Sri Ramakrishna (1836 –1886), spoke at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago and won an enthusiastic American following with his genteel manner and erudite presentation. Over the next few years, he inaugurated the first Eastern religious movement in America: the Vedanta Societies of various cities, independent of one another but under the spiritual leadership of the Ramakrishna Order in India. In 1920 a second Hindu missionary effort was launched in America when a comparably charismatic “neo -Vedanta” swami, Paramahansa Yogananda, was invited to speak at the International Congress of Religious Liberals in Boston, sponsored by the Unitarian Church. After the Congress, Yogananda lectured across the country, spellbinding audiences with his immense charm and powerful presence. In 1925 he established the headquarters for his Self -Realization Fellowship (SRF) in Los Angeles on the site of a former hotel atop Mount Washington. He was the first Eastern guru to take up permanent residence in the United States after creating a following here. NEO-VEDANTA: THE FORCE STRIKES BACK Neo-Vedanta arose partly as a countermissionary movement to Christianity in nineteenth -century India. Having lost a significant minority of Indians (especially among the outcast “Untouchables”) to Christianity under British rule, certain adherents of the ancient Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism retooled their religion to better compete with Christianity for the s ouls not only of Easterners, but of Westerners as well. -

Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2015 Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks Kimberley J. Pingatore As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Pingatore, Kimberley J., "Bodies Bending Boundaries: Religious, Spiritual, and Secular Identities of Modern Postural Yoga in the Ozarks" (2015). MSU Graduate Theses. 3010. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/3010 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, Religious Studies By Kimberley J. Pingatore December 2015 Copyright 2015 by Kimberley Jaqueline Pingatore ii BODIES BENDING BOUNDARIES: RELIGIOUS, SPIRITUAL, AND SECULAR IDENTITIES OF MODERN POSTURAL YOGA IN THE OZARKS Religious Studies Missouri State University, December 2015 Master of Arts Kimberley J. -

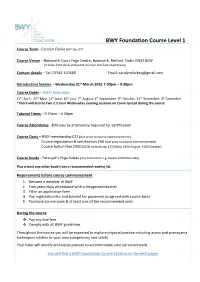

BWY Foundation Course Level 1

BWY Foundation Course Level 1 Course Tutor - Carolyn Clarke BWY Dip: DCT Course Venue – Babworth Court Yoga Centre, Babworth, Retford, Notts DN22 8EW (2 miles from A1 & accessible on main line East coast trains) Contact details – Tel: 07561 107660 Email: [email protected] Introductory Session – Wednesday 31st March 2021 7.00pm – 9.30pm Course Dates – 2021- Saturdays 17th April: 22nd May: 12th June: 10th July: 7th August: 4th September: 9th October: 13th November: 4th December *There will also be two 2.5 hour Wednesday evening sessions on Zoom spread during the course Tutorial Times – 9.45am – 4.30pm Course Attendance - 80% course attendance required for certification Course Costs – BWY membership £37 (due prior to course commencement) Course registration & certification £60 (due prior to course commencement) Course tuition fees £500 (£100 on booking: £150 May: £150 August: £100 October) Course books - Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (any translation e.g. Swami Satchidananda) Plus a least one other book from a recommended reading list Requirements before course commencement 1. Become a member of BWY 2. Two years class attendance with a recognised teacher 3. Fill in an application form 4. Pay registration fee and tutorial fee payments as agreed with course tutor 5. Purchase course book & at least one of the recommended ones During the course v Pay any due fees v Comply with all BWY guidelines Throughout the course you will be expected to explore physical practice including asana and pranayama techniques relative to your own competency and safety. Your tutor will modify and adjust posture to accommodate your personal needs. You will find a BWY Foundation Course Syllabus on the next pages BRITISH WHEEL OF YOGA SYLLABUS - FOUNDATION COURSE 1 The British Wheel of Yoga Foundation Course 1 focuses on basic practical techniques and personal development taught in the context of the philosophy that underpins Yoga. -

923 11.Satyanarayan

Impact Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research JournalISSN (AIIRJ) 2349- 638x Vol - IV FactorIssue-VII JULY 2017 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 3.025 3.025 Refereed And Indexed Journal AAYUSHI INTERNATIONAL INTERDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH JOURNAL (AIIRJ) Monthly Publish Journal VOL-IV ISSUE-VII JULY 2017 •Vikram Nagar, Boudhi Chouk, Latur. Address •Tq. Latur, Dis. Latur 413512 (MS.) •(+91) 9922455749, (+91) 9158387437 •[email protected] Email •[email protected] Website •www.aiirjournal.com CHIEF EDITOR – PRAMOD PRAKASHRAO TANDALE Email id’s:- [email protected], [email protected] I Mob.09922455749 Page website :- www.aiirjournal.com No.46 Aayushi International Interdisciplinary Research Journal (AIIRJ) Vol - IV Issue-VII JULY 2017 ISSN 2349-638x Impact Factor 3.025 Concept of Yoga: Origin and History Satyanarayan Mishra, Research Scholar,Yoga, Utkal University,Vani Vihar, Bhubaneswar,Odisha Abstract The exact Origin and history of Yoga is somehow obscure and uncertain as it has been transmitted orally from Gurus and authors of sacred texts to the successors and the secretive nature of the valuable teachings. Early teachings on yoga were recorded on fragile palm leaves which got lost or damaged in course of time. Yoga practice is believed to have its origin with the very dawn of civilization. Long before the religions or beliefs were created the science of yoga has its origin as believed. Prevedic yoga, Vedic Yoga, Preclassical Yoga, Classical Yoga, Postclassical Yoga and Modern period. Attempt has been made to discuss the concept, origin and history of yoga in this article. Keywords:- Shiva,pre-vedic yoga,vedic yoga,post vedic yoga,pre-classical yoga,classical yoga Introduction We can trace back the development of yoga to over 5,000 years ago, while according to some researchers origin of yoga may be up to 10,000 years old . -

Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS

Breath of Life Yoga and the Five Prana Vayus CONTENTS Prana Vayu: 4 The Breath of Vitality Apana Vayu: 9 The Anchoring Breath Samana Vayu: 14 The Breath of Balance Udana Vayu: 19 The Breath of Ascent Vyana Vayu: 24 The Breath of Integration By Sandra Anderson Yoga International senior editor Sandra Anderson is co-author of Yoga: Mastering the Basics and has taught yoga and meditation for over 25 years. Photography: Kathryn LeSoine, Model: Sandra Anderson; Wardrobe: Top by Zobha; Pant by Prana © 2011 Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A. All rights reserved. Reproduction or use of editorial or pictorial content in any manner without written permission is prohibited. Introduction t its heart, hatha yoga is more than just flexibility or strength in postures; it is the management of prana, the vital life force that animates all levels of being. Prana enables the body to move and the mind to think. It is the intelligence that coordinates our senses, and the perceptible manifestation of our higher selves. By becoming more attentive to prana—and enhancing and directing its flow through the Apractices of hatha yoga—we can invigorate the body and mind, develop an expanded inner awareness, and open the door to higher states of consciousness. The yoga tradition describes five movements or functions of prana known as the vayus (literally “winds”)—prana vayu (not to be confused with the undivided master prana), apana vayu, samana vayu, udana vayu, and vyana vayu. These five vayus govern different areas of the body and different physical and subtle activities. -

Asana Sarvangasana

Sarvângâsana (Shoulder Stand) Compiled by: Trisha Lamb Last Revised: April 18, 2006 © 2004 by International Association of Yoga Therapists (IAYT) International Association of Yoga Therapists P.O. Box 2513 • Prescott • AZ 86302 • Phone: 928-541-0004 E-mail: [email protected] • URL: www.iayt.org The contents of this bibliography do not provide medical advice and should not be so interpreted. Before beginning any exercise program, see your physician for clearance. Benagh, Barbara. Salamba sarvangasana (shoulderstand). Yoga Journal, Nov 2001, pp. 104-114. Cole, Roger. Keep the neck healthy in shoulderstand. My Yoga Mentor, May 2004, no. 6. Article available online: http://www.yogajournal.com/teacher/1091_1.cfm. Double shoulder stand: Two heads are better than one. Self, mar 1998, p. 110. Ezraty, Maty, with Melanie Lora. Block steady: Building to headstand. Yoga Journal, Jun 2005, pp. 63-70. “A strong upper body equals a stronger Headstand. Use a block and this creative sequence of poses to build strength and stability for your inversions.” (Also discusses shoulder stand.) Freeman, Richard. Threads of Universal Form in Back Bending and Finishing Poses workshop. 6th Annual Yoga Journal Convention, 27-30 Sep 2001, Estes Park, Colorado. “Small, subtle adjustments in form and attitude can make problematic and difficult poses produce their fruits. We will look a little deeper into back bends, shoulderstands, headstands, and related poses. Common difficulties, injuries, and misalignments and their solutions [will be] explored.” Grill, Heinz. The shoulderstand. Yoga & Health, Dec 1999, p. 35. ___________. The learning curve: Maintaining a proper cervical curve by strengthening weak muscles can ease many common pains in the neck. -

“White Ball” Qigong in Perceptual Auditory Attention

The acute Effect of “White Ball” Qigong in Perceptual auditory Attention - a randomized, controlled study done with Biopac Reaction Time measurements - Lara de Jesus Teixeira Lopes Mestrado em Medicina Tradicional Chinesa Porto 2015 Lara de Jesus Teixeira Lopes The acute effect of White Ball Qigong in perceptual auditory Attention - a randomized controlled study done with Biopac Reaction Time measurements - Dissertação de Candidatura ao grau de Mestre em Medicina Tradicional Chinesa submetida ao Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas de Abel Salazar da Universidade do Porto. Orientador - Henry Johannes Greten Categoria - Professor Associado Convidado Afiliação - Instituto de Ciências Biomédicas Abel Salazar da Universidade do Porto. Co-orientador – Maria João Santos Categoria – Mestre de Medicina Tradicional Chinesa Afiliação – Heidelberg School of Traditional Chinese Medicine Resumo Enquadramento: A correlação entre técnicas de treino corpo-mente e a melhoria da performance cognitiva dos seus praticantes é um tópico de corrente interesse público. Os seus benefícios na Atenção, gestão de tarefas múltiplas simultâneas, mecanismos de autogestão do stress e melhorias no estado geral de saúde estão documentados. Qigong é uma técnica terapêutica da MTC com enorme sucesso clínico na gestão emocional e cognitiva. [6] [8-9] [13-14] [16] [18-20] [26-30] [35-45] Um dos problemas nas pesquisas sobre Qigong é a falta de controlos adequados. Nós desenvolvemos, recentemente, um Qigong Placebo e adoptamos essa metodologia no presente estudo. Pretendemos investigar se a prática única do Movimento “Bola Branca” do Qigong, durante 5 minutos, melhora a Atenção Auditiva Perceptual ou se é necessário uma prática regular mínima para obter os potenciais efeitos. Objetivos: 1. Analisar o efeito agudo de 5 minutos de treino de Qigong sobre a Atenção Auditiva Perceptual, medida por tempo de reacção. -

Yoga Anatomy / Leslie Kaminoff, Amy Matthews ; Illustrated by Sharon Ellis

Y O G A ANATOMY second edItIon leslie kaminoff amy matthews Illustrated by sharon ellis Human kinetics Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaminoff, Leslie, 1958- Yoga anatomy / Leslie Kaminoff, Amy Matthews ; Illustrated by Sharon Ellis. -- 2nd ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-0024-4 (soft cover) ISBN-10: 1-4504-0024-8 (soft cover) 1. Hatha yoga. 2. Human anatomy. I. Matthews, Amy. II. Title. RA781.7.K356 2011 613.7’046--dc23 2011027333 ISBN-10: 1-4504-0024-8 (print) ISBN-13: 978-1-4504-0024-4 (print) Copyright © 2012, 2007 by The Breathe Trust All rights reserved. Except for use in a review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying, and recording, and in any information storage and retrieval system, is forbidden without the written permission of the publisher. This publication is written and published to provide accurate and authoritative information relevant to the subject matter presented. It is published and sold with the understanding that the author and publisher are not engaged in rendering legal, medical, or other professional services by reason of their authorship or publication of this work. If medical or other expert assistance is required, the services of a competent professional person should be sought. The web addresses cited in this text were current as of August 2011, unless otherwise noted. Managing Editor: Laura Podeschi; Assistant Editors: Claire Marty and Tyler Wolpert; Copyeditor: Joanna Hatzopoulos Portman; Graphic Designer: Joe Buck; Graphic Artist: Tara Welsch; Original Cover Designer and Photographer (for illustration references): Lydia Mann; Photo Production Manager: Jason Allen; Art Manager: Kelly Hendren; Associate Art Manager: Alan L. -

Course Details the British Wheel of Yoga (BWY)

Course Details me to observe your posture work and see how you interact within a group. The British Wheel of Yoga (BWY) Diploma Course is designed to train I will also set you some written work to give you a real flavour of the committed yoga practitioners to be safe and effective teachers of yoga. course. At this stage you are still not committing yourself to the course The course is in four modules: and will need to seriously consider whether you intend to progress further. All students wishing to join the course must join BWY and pay the course Unit 1 Anatomy and physiology related to yoga practice, stress and relaxation, nutrition, deposit prior to the commencement of the first course day. basic breathing and the setting up of a yoga class. Selected practices. Course Set Books Unit 2 Prana, pranayama, mudras, bandhas, chakras, Hatha Yoga Pradipika and All students are required to own the set books: observation and analysis in teaching. Selected practices An Anatomy and Physiology text. Unit 3 Yoga philosophy, concentration, meditation, mantra, issues of health and safety in Yoga Sutras of Patanjali teaching and first aid. Selected practices. Hatha Yoga Pradipika Bhagavad Gita Unit 4 Professional studies and practical aspects of teaching yoga postures. Selected practices. The Major Upanishads Adult Learning, Adult Teaching Daines, Daines and Graham The course will consist of monthly meetings 9.30am – 4.30pm and two Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha Swami Satyananda weekend residentials over 3 years. Students are required to continue regular attendance at a weekly class with a BWY teacher; follow home There are a number of translations of the texts and information will be study and home practice schedules; to complete written work and to given at the Introductory Day about the books to be used during the prepare presentations and mini teaching sessions to be given during course. -

Biofeedback- an Intervention to Regulate Occupational Stress

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 21, Issue 3, Ver. I (Mar. 2016) PP 94-96 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org Biofeedback- An Intervention To Regulate Occupational Stress B.Prathyusha1, Dr. Ch. S. Durga Prasad2, Dr. M. Sudhir Reddy3 1(Department Of Humanities and Sciences, VNR Vignana Jyothi Institute of Engineering & Technology, India) 2(HR & OB, Vignana Jyothi Institute of Management, India) 3(In-Charge, NITMS, Jawaharlal Nehru Technological University, India) Abstract : The main aim of this paper is to create awareness to the readers about Biofeedback as a technique to control Occupational Stress. Occupational stress has a real and significant effect on health and performance in personal life and at the workplace. The perils of stress are well-documenated. Prolonged stress results in release of many anti-stress chemicals in the body which lead to disrupt of chemical balance and weakens the systems of the body. A great way to reduce stress is to use Biofeedback devices. It helps to monitor how body respond to negative stimuli and helps in eliminating stress. Biofeedback is built on the concept of “mind over matter”. Biofeedback is a research-based learning process in which people are taught to improve their health and performance by observing signals generated by their own bodies to stressors and other stimuli with an eclectic variety of instruments. It offers a unique, non-invasive window on body's stress level. It is scientific based and validated by research studies and clinical practice. It is a highly effective way to control stress and helps in achieving personal and professional goals. -

To Download the 2019

11 th & 12th May 2019 EventCity, Manchester M17 8AS (sat nav) omyogashow.com 1 SUBSCRIBE TO at our stand B1 PLUS receive a FREE Goodie bag WORTH £30 Subscribe to OM Yoga Magazine at the show on stand B1 and save 33% 12 issues for just £45 - that’s a saving of 25%! ommagazine.com 2 WELCOME 11TH & 12TH May 2019 EventCity, Manchester M17 8AS (sat nav) Are you ready Manchester? The OM Yoga Show is heading back to EventCity for another epic weekend of yoga. Thank you to our sponsors Yoga is for everybody and every body, so it’s time to leave your worries at the door, and get on the mat! There’s so much choice in the world of yoga, but once you nd your favourite style of yoga, you’ll never look back. The OM Yoga Show has something for everyone, and it’s the perfect place to nd your groove. Free open classes are taking place throughout the entire weekend; learn from teachers who are on hand to provide advice, guidance, and inspiration. You’re in the very best of hands! For those who want to get a little more in-depth, head over to the workshop desk and book onto one of our more in-depth sessions. And if you’ve always been meaning to try hot yoga but never had the chance, now is the time! Hotpod Yoga’s inatable pod is heated to a perfect 37 degrees to give you the perfect hot yoga class. No OM Yoga Show is complete without a showcase of exhibitors to ll your shopping bags with everything you need to fully embrace a yoga life.