Assembly Committee on Ways and Means-February 21, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nevada Judicial Directory

NEVADA JUDICIAL DIRECTORY www.nevadajudiciary.us PREPARED BY: MARK GIBBONS ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS CHIEF JUSTICE TABLE OF CONTENTS SUPREME COURT OF NEVADA ......................................................................................................................1 OFFICE OF THE CLERK ...................................................................................................................................2 CENTRAL STAFF ................................................................................................................................................2 LAW LIBRARY.....................................................................................................................................................2 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS ............................................................................................3 SENIOR JUDGES .................................................................................................................................................6 DISTRICT COURTS.............................................................................................................................................8 JUSTICES OF THE PEACE ..............................................................................................................................28 MUNICIPAL COURT JUDGES ........................................................................................................................37 JUSTICE AND MUNICIPAL COURT ADMINISTRATORS .....................................................................441 -

Directory of State and Local Government

DIRECTORY OF STATE AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT Prepared by RESEARCH DIVISION LEGISLATIVE COUNSEL BUREAU 2020 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS Please refer to the Alphabetical Index to the Directory of State and Local Government for a complete list of agencies. NEVADA STATE GOVERNMENT ORGANIZATIONAL CHART ............................................. D-9 CONGRESSIONAL DELEGATION ............................................................................................. D-13 DIRECTORY OF STATE GOVERNMENT CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS: Attorney General ........................................................................................................................ D-15 State Controller ........................................................................................................................... D-19 Governor ..................................................................................................................................... D-20 Lieutenant Governor ................................................................................................................... D-27 Secretary of State ........................................................................................................................ D-28 State Treasurer ............................................................................................................................ D-30 EXECUTIVE BOARDS ................................................................................................................. D-31 NEVADA SYSTEM OF HIGHER EDUCATION -

Nevada's Major Elected Officers

RESEARCH DIVISION STAFF STATE OF NEVADA [email protected] MAJOR ELECTED OFFICERS JANUARY 2021 CONSTITUTIONAL OFFICERS, EXECUTIVE BRANCH https://gov.nv.gov 101 North Carson Street, Suite 1 555 East Washington Avenue, Suite 5100 GOVERNOR Carson City, NV 89701 Las Vegas, NV 89101 (See Chapter 223 of Nevada Revised Statutes [NRS] for duties and responsibilities.) Telephone: (775) 684-5670 Telephone: (702) 486-2500 Steve Sisolak (D) Fax: (775) 684-5683 Fax: (702) 486-2505 101 North Carson Street, Suite 2 555 East Washington Avenue, Suite 5500 LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR https://ltgov.nv.gov Carson City, NV 89701 Las Vegas, NV 89101 (See Chapter 224 of NRS for duties Telephone: (775) 684-7111 Telephone: (702) 486-2400 Kate Marshall (D) and responsibilities.) Fax: (775) 684-7110 Fax: (702) 486-2404 Securities Division 101 North Carson Street, Suite 3 2250 Las Vegas Boulevard North, Suite 400 SECRETARY OF STATE https://nvsos.gov/sos Carson City, NV 89701 North Las Vegas, NV 89030 (See Chapter 225 of NRS for duties Telephone: (775) 684-5708 Telephone: (702) 486-2440 Barbara K. Cegavske (R) and responsibilities.) Fax: (775) 684-5725 Fax: (702) 486-2452 [email protected] [email protected] College Savings: Telephone: (702) 486-6980 101 North Carson Street, Suite 4 [email protected] Carson City, NV 89701 Millennium Scholarship: Telephone: (702) 486-3383 http://nevadatreasurer.gov Telephone: (775) 684-5600 STATE TREASURER Fax: (775) 684-5781 [email protected] (See Chapter 226 of NRS for duties and Prepaid Tuition: -

2019 Annual Report of the Nevada Judiciary on Behalf of the Supreme Court of Nevada and the Entire Nevada Judiciary

ANNUAL REPORT of the NEVADA JUDICIARY Fiscal Year 2019 Equal Branches of Government LEGISLATIVE BRANCH TO MAKE THE LAWS. LEGISLATIVE EXECUTIVE BRANCH TO ENACT THE LAWS. JUDICIAL BRANCH TO INTERPRET THE LAWS. JUDICIAL "The effect of [a representative democracy is] to refine and enlarge the public views, by passing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of the nation..." - James Madison EXECUTIVE "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases, must of necessity expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the courts must decide on the operation of each." - John Marshall “If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more and become more, you are a leader.” - John Quincy Adams Nevada Judiciary Annual Report Table of Contents CHIEF JUSTICE LETTER 3 STATE COURT ADMINISTRATOR NOTE 4 FISCAL OVERVIEW 5 YEAR IN REVIEW 8 THE JUDICIARY IN MEMORIAM 11 The Nevada Judiciary interprets laws STATE OF THE JUDICIARY 12 and provides an unbiased check on the Executive and Legislative branches. The JUDICIAL COUNCIL OF THE STATE OF NEVADA 17 Nevada Judiciary has the responsibility to COMMITTEES AND COMMISSIONS 18 dispute resolution in legal matters. COURT INNOVATION 24 provideAlthough impartial, a efficient,separate and branch accessible of government, the Nevada Judiciary works JUDICIAL PROGRAMS AND SERVICES 26 with the other branches to serve the citizens of Nevada. NEVADA JUDICIARY 33 APPELLATE COURTS SUMMARY 36 TRIAL COURT OVERVIEW 38 JUDICIAL DISTRICT SUMMARY 40 SPECIALTY COURT SUMMARY 51 Expanded program notes and full statistics can be found on our website at https://nvcourts.link/NVJAnnualReport. -

Pro Bono Awards Luncheon

17TH ANNUAL Pro Bono Awards Luncheon DECEMBER 8, 2017 | THE RIO ALL-SUITE HOTEL AND CASINO Preserving access to justice for our community’s most vulnerable residents through the generous contributions of volunteer attorneys. Remarks MAXIMILIANO COUVILLIER President, Board of Directors, Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada BARBARA BUCKLEY Executive Director, Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada NOAH MALGERI Pro Bono Project Director, Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada Award Presentations ASK-A-LAWYER COMMUNITY COMMITMENT AWARD Presented by Justice Mark Gibbons, Nevada Supreme Court This award recognizes a volunteer who has demonstrated tremendous commitment to the Ask-A-Lawyer Program. PUBLIC INTEREST LAW STUDENT OF DISTINCTION Presented by Justice Ron Parraguirre, Nevada Supreme Court This award recognizes a law student who has made a substantial commitment to the community by doing public interest work and promoting access to justice. VOLUNTEER EDUCATION ADVOCATE AWARD Presented by Justice Kristina Pickering, Nevada Supreme Court This award recognizes a non-attorney volunteer who has made a difference in the life of a child with special educational needs. JUSTICE NANCY BECKER PRO BONO AWARD OF JUDICIAL EXCELLENCE Presented by The Honorable Nancy Becker This award, given in honor of Nancy Becker, one of the founders of the Pro Bono Project and a strong advocate for access to justice, recognizes members of the judiciary who have given their time, energy and influence to encourage pro bono work and access to justice. MYRNA WILLIAMS CHILDREN’S PRO BONO AWARD Presented by Myrna Williams, Former County Commissioner/State Legislator This award, given in honor of Myrna Williams, an instrumental force in obtaining legal representation for abused children in foster care, recognizes an attorney who made an extraordinary difference in the life of a child. -

The Clark County Election Department Joseph P

2020 JUDICIAL CANDIDATE GUIDE Prepared By The Clark County Election Department Joseph P. Gloria, Registrar of Voters Board of County Commissioners Marilyn Kirkpatrick, Chair · Lawrence Weekly, Vice-Chair Larry Brown · James B. Gibson · Justin Jones · Michael Naft · Tick Segerblom Yolanda King, County Manager Date: Jan. 21, 2020 T C Table of Contents. 1 Filing Dates, Locations, and Fees . 2 Document Filing Schedules . 4 Candidate Filing Process and Requirements . 5 2020 Checklist for Judicial Candidate Filing . 9 Campaign Practices / Ethics and Electioneering / Signs . 10 Public Observation of Voting . 13 Registering Voters . 14 Mail / Absentee Ballots. 15 What’s New in Nevada Elections . 17 Judicial Offices up for Election in 2020. 21 Justice of the Supreme Court. 23 Court of Appeals Judge . 25 District Court Judge, 8th Judicial District . 27 Justice of the Peace . 31 APPENDIX . 34 Important Dates. 35 Contact Us . 37 Locations / Maps . 38 Election Related Contacts . 39 Information / Reports . 40 Ballots. 43 Election Results . 45 Early Voting . 46 Posting Logs. 48 1 F D, L, F When, Where, and Fees When: Judicial candidates may file to run for office from Monday, January 6, 2020 to Friday, January 17, 2020, 8:00 a.m.-5:00 p.m., except weekends and holidays. The last day to change how a name will appear on the ballot is Friday, January 17, 2020. The last day to withdraw candidacy or rescind withdrawal of candidacy is Wednesday, January 29, 2020. Where: Candidates must file with the appropriate filing officer, as listed below and on the next page. Fees: Candidates must pay the required fees, listed below and on the next page. -

Table of Contents

NEVADA JUDICIAL DIRECTORY www.nvcourts.gov PREPARED BY: JAMES W. HARDESTY ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS CHIEF JUSTICE TABLE OF CONTENTS SUPREME COURT OF NEVADA ......................................................................................................................1 NEVADA COURT OF APPEALS .......................................................................................................................2 OFFICE OF THE CLERK ...................................................................................................................................3 CENTRAL STAFF ................................................................................................................................................3 LAW LIBRARY.....................................................................................................................................................3 ADMINISTRATIVE OFFICE OF THE COURTS ............................................................................................4 SENIOR JUDGES .................................................................................................................................................7 DISTRICT COURTS...........................................................................................................................................10 JUSTICES OF THE PEACE ..............................................................................................................................30 MUNICIPAL COURT JUDGES ........................................................................................................................39 -

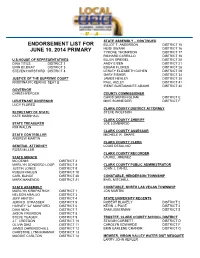

Endorsement List for June 10, 2014 Primary

The United Association STATE ASSEMBLY – CONTINUED ENDORSEMENT LIST FOR ELLIOT T. ANDERSON DISTRICT 15 HEIDI SWANK DISTRICT 16 JUNE 10, 2014 PRIMARY TYRONE THOMPSON DISTRICT 17 RICHARD CARRILLO DISTRICT 18 U.S.HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELLEN SPIEGEL DISTRICT 20 DINA TITUS DISTRICT 1 ANDY EISEN DISTRICT 21 ERIN BILBRAY DISTRICT 3 EDGAR FLORES DISTRICT 28 STEVEN HORSFORD DISTRICT 4 LESLEY ELIZABETH COHEN DISTRICT 29 GARY FISHER DISTRICT 34 JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT JAMES HEALEY DISTRICT 35 KRISTINA PICKERING SEAT B PAUL AIZLEY DISTRICT 41 IRENE BUSTAMANTE ADAMS DISTRICT 42 GOVERNOR CHRIS HYEPOCK COUNTY COMMISSIONER CHRIS GIUNCHIGLIANI DISTRICT E LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR MIKE SCHNEIDER DISTRICT F LUCY FLORES CLARK COUNTY DISTRICT ATTORNEY SECRETARY OF STATE STEVE WOLFSON KATE MARSHALL CLARK COUNTY SHERIFF STATE TREASURER JOE LOMBARDO KIM WALLIN CLARK COUNTY ASSESSOR STATE CONTROLLER MICHELE W. SHAFE ANDREW MARTIN CLARK COUNTY CLERK GENERAL ATTORNEY LOUIS DESALVIO ROSS MILLER CLARK COUNTY RECORDER STATE SENATE LAUREL JIMENEZ MO DENIS DISTRICT 2 MARILYN DONDERO LOOP DISTRICT 8 CLARK COUNTY PUBLIC ADMINISTRATOR JUSTIN JONES DISTRICT 9 JOHN J. CAHILL RUBEN KIHUEN DISTRICT 10 CARL BUNCE DISTRICT 20 CONSTABLE, HENDERSON TOWNSHIP MARK MANENDO DISTRICT 21 EARL MITCHELL STATE ASSEMBLY CONSTABLE, NORTH LAS VEGAS TOWNSHIP MARILYN KIRKPATRICK DISTRICT 1 JON MARTIN NELSON ARAUJO DISTRICT 3 JEFF HINTON DISTRICT 4 STATE UNIVERSITY REGENTS JERRI D. STRASSER DISTRICT 5 ROBERT BLAKELY DISTRICT 2 HARVEY “JJ” MUNFORD DISTRICT 6 KEVIN J. PAGE DISTRICT 3 DINA NEAL DISTRICT 7 SAM LIEBERMAN DISTRICT 5 JASON FRIERSON DISTRICT 8 STEVE YEAGER DISTRICT 9 TRUSTEE, CLARK COUNTY SCHOOL DISTRICT J.T. CREEDON DISTRICT 10 STAVAN CORBETT DISTRICT D OLIVIA DIAZ DISTRICT 11 CAROLYN EDWARDS DISTRICT F JAMES OHRENSCHALL DISTRICT 12 ERIN EARLENE CRANOR DISTRICT G CHRISTINE LYNN KRAMAR DISTRICT 13 MAGGIE CARLTON DISTRICT 14 MEMBER, VIRGIN VALLEY WATER DIST MESQUITE LARRY JOHN KEPLER DISTRICT COURT JUDGE WILLIAM SKUPA DEPARTMENT 2 DOUGLAS W. -

NEVADA Teamster November 3 ENDORSEMENTS

NEVADA Teamster November 3 ENDORSEMENTS U.S. PRESIDENT UNIVERSITY REGENTS STATE ASSEMBLY Joe Biden #5 Nick Spirtos #1 Danielle Monroe-Moreno #2 Radhika Kunnel STATE BOARD OF ED. U.S. Vice President #3 Selena Torres #1 Timothy Hughes #4 Connie Munk Kamala Harris #2 Katie Coombs #5 Brittney Miller #4 Mark Newburn #6 Shondra Summers- U.S. CONGRESS Armstrong CLARK COUNTY #1 Dina Titus #7 Cameron Miller Commission #2 Patricia Ackerman #8 Jason Frierson A – Michael Naft #3 Susie Lee #9 Steve Yeager #4 Steven Horsford B – Marilyn Kirkpatrick C – Ross Miller #10 Rochelle Nguyen D – William McCurdy II #11 Bea Duran STATEWIDE QUESTIONS #12 Susan Martinez #1 YES School District Trustee #13 Thomas Roberts #2 YES A – Lisa Guzman #14 Maggie Carlton #6 YES B – Jeffrey Proffitt #15 Howard Watts II C – Tameka Henry #16 Cecelia Gonzalez JUDICIAL E – Alexis Salt #17 Claire Thomas Supreme Court #18 Venecia Considine B - Kristina Pickering RENO #20 David Orentlicher D – Ozzie Fumo Ward 1 Jenny Brekhus #21 Elaine Marzola Ward 3 Oscar Delgado #24 Sarah Peters Ward 5 No recommendation Court of Appeals #26 Vance Aim At-Large Devon Reese #27 Teresa Benitez- Bonnie Bulla Thompson SPARKS #28 Edgar Flores Ward 1 Wendy Stolyarov #29 Lesley Cohen Ward 3 Quentin Smith #30 Natha Anderson STATE SENATE Ward 5 No recommendation #1 Pat Spearman #31 Richard “Skip” Daly #32 Paula Povilaitis #3 Chris Brooks WASHOE COUNTY #34 Shannon-Bilbray-Axelrod #4 Dina Neil Commission #35 Michelle Gorelow #5 Kristee Watson #1 Alexis Hill #6 Nicole Cannizzaro #4 No recommendation #37 Shea Backus #7 Roberta Lange #39 Deborah Chang #11 Dallas Harris School District #40 Sena Loyd #15 Wendy Juaregui-Jackins A – Scott Kelly #18 Liz Becker D – Kurt Thigpen E – Angie Taylor G – Craig Wesner . -

March 4, 2020 Meeting Notice and Agenda

BOARD OF PARDONS STATE OF NEVADA STEVE SISOLAK GOVERNOR, CHAIRMAN ADDRESS ALL COMMUNICATIONS TO: AARON D. FORD ATTORNEY GENERAL, MEMBER PARDONS BOARD KRISTINA PICKERING 1677 OLD HOT SPRINGS ROAD CHIEF JUSTICE, MEMBER SUITE A CARSON CITY, NEVADA 89706 MARK GIBBONS TELEPHONE (775) 687-6568 JUSTICE, MEMBER FAX (775) 687-6736 JAMES W. HARDESTY JUSTICE, MEMBER DENISE DAVIS, EXECUTIVE SECRETARY RONALD D. PARRAGUIRRE JUSTICE, MEMBER LIDIA S. STIGLICH BOARD OF PARDONS JUSTICE, MEMBER ELISSA F. CADISH JUSTICE, MEMBER ABBI SILVER JUSTICE, MEMBER MEETING NOTICE AND AGENDA Date and Time: 9:00 AM – Wednesday, March 4, 2020 Location: Nevada Supreme Court 201 South Carson Street, Carson City, Nevada & Video Conference to Nevada Supreme Court 408 East Clark Avenue Las Vegas, Nevada The State Board of Pardons Commissioners (Board) will consider commuting sentences, granting pardons and restoring the civil rights of the applicants listed on this agenda. The Board may take action to commute or modify the sentence of a prisoner, grant a full and unconditional pardon**, grant a conditional pardon***, deny a request, or take no action on a request. The Pardons Board may restore the right to bear arms to an applicant even if the applicant has not specifically requested such action. Items on the agenda may be taken out of order. The Board may combine two or more agenda items for consideration. The Board may remove an item from the agenda or delay discussion relating to an item on the agenda at any time. The Board may place reasonable restrictions on the time, place, and manner of public comments; however, comments based on viewpoint will not be restricted. -

Pro Bono Awards Luncheon

19th ANNUAL Thank You to our Luncheon Sponsors Pro Bono Awards Luncheon DECEMBER 13, 2019 WYNN LAS VEGAS Preserving access to justice for our community’s most vulnerable residents through the generous contributions of volunteer attorneys REMARKS BARBARA BUCKLEY Executive Director, Legal Aid Center of Southern Nevada CHIEF JUSTICE MARK GIBBONS Nevada Supreme Court AWARD PRESENTATIONS ASK-A-LAWYER COMMUNITY COMMITMENT AWARD Presented by Justice Elissa F. Cadish, Nevada Supreme Court This award is given to a volunteer with tremendous commitment to the Ask-A-Lawyer Program. PUBLIC INTEREST LAW STUDENT OF DISTINCTION Presented by Justice Ron Parraguirre, Nevada Supreme Court This award recognizes a law student who has made a substantial commitment to the community by doing public interest work and promoting access to justice. VOLUNTEER EDUCATION ADVOCATE AWARD Presented by Senior Justice Michael Cherry, Nevada Supreme Court This award recognizes a non-attorney volunteer who has made a difference in the life of a child with special educational needs. JUSTICE NANCY BECKER PRO BONO AWARD OF JUDICIAL EXCELLENCE Presented by the Honorable Nancy Becker This award, given in honor of Nancy Becker, one of the founders of the Pro Bono Project and a strong advocate for access to justice, recognizes members of the judiciary who have given their time, energy and influence to encourage pro bono work and access to justice. MYRNA WILLIAMS CHILDREN’S PRO BONO AWARD Presented by Senior Justice Michael Douglas on behalf of Myrna Williams This award, given in honor of Myrna Williams, an instrumental force in obtaining legal representation for abused children in foster care, recognizes an attorney who made an extraordinary difference in the life of a child. -

2013 Annual Report

Annual Report of the Nevada Judiciary Fiscal Year 2013 Nevada Supreme Court Front Row: Justice James W. Hardesty, Chief Justice Kristina Pickering, and Justice Michael L. Douglas Back Row: Associate Chief Justice Mark Gibbons, Justice Michael A. Cherry, Justice Nancy M. Saitta, and Justice Ron D. Parraguirre ANNUAL REPORT OF THE NEVADA JUDICIARY JULY 1, 2012 - JUNE 30, 2013 Table of Contents Nevada's Court Structure..................................................2 A Note from the Chief Justice..........................................3 Carson City Clark County A Note from the State Court Administrator......................4 Funding the Nevada Judiciary..........................................5 State of the Judiciary Message.........................................8 Nevada Court of Appeals................................................13 Douglas County Humboldt County Lyon County Judicial Council of the State of Nevada.........................15 Commissions and Committees.......................................16 Work of the Courts..........................................................19 Pershing County Washoe County Foreclosure Mediation....................................................27 Architect Frederick DeLongchamps Many of the historic courthouses in Nevada were The Nevada Judiciary Court Programs designed by Architect Frederick DeLongchamps. The most and Caseload Report famous is the unique Pershing County Courthouse pictured on the cover, which is believed to contain the last round Uniform System for Judicial Records............................30