Bregje De Jong | 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Media Guide of Australia at the 2014 Fifa World Cup Brazil 0

OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL 0 Released: 14 May 2014 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA TM AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP Version 1 CONTENTS Media information 2 2014 FIFA World Cup match schedule 4 Host cities 6 Brazil profile 7 2014 FIFA World Cup country profiles 8 Head-to-head 24 Australia’s 2014 FIFA World Cup path 26 Referees 30 Australia’s squad (preliminary) 31 Player profiles 32 Head coach profile 62 Australian staff 63 FIFA World Cup history 64 Australian national team history (and records) 66 2014 FIFA World Cup diary 100 Copyright Football Federation Australia 2014. All rights reserved. No portion of this product may be reproduced electronically, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of Football Federation Australia. OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUPTM A publication of Football Federation Australia Content and layout by Andrew Howe Publication designed to print two pages to a sheet OFFICIAL MEDIA GUIDE OF AUSTRALIA AT THE 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL 1 MEDIA INFORMATION AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL TEAM / 2014 FIFA WORLD CUP BRAZIL KEY DATES AEST 26 May Warm-up friendly: Australia v South Africa (Sydney) 19:30 local/AEST 6 June Warm-up friendly: Australia v Croatia (Salvador, Brazil) 7 June 12 June–13 July 2014 FIFA World Cup Brazil 13 June – 14 July 12 June 2014 FIFA World Cup Opening Ceremony Brazil -

Funding Sport Fairly an Income-Contingent Loans Scheme for Elite Sports Training

THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE Funding Sport Fairly An income-contingent loans scheme for elite sports training Background Australian taxpayers spent more than $97 million on elite sportspeople in 2001-2002 (ASC 2002). A significant proportion of this expenditure went on providing Australian Institute of Sport (AIS) ‘scholarships’ to 673 athletes and grants to national sporting bodies for their elite athlete programs (ASC 2002). Major expenses associated with assistance to elite sportspeople include the provision of training facilities (such as swimming pools and playing fields), coaching, medical advice and international and domestic travel costs associated with competition. While there is no doubt that the Commonwealth Government has a role to play in encouraging excellence in all fields of human endeavour, be they sporting, educational or artistic, there is an important equity issue associated with providing taxpayer funded training to individuals who go on to earn millions of dollars per year from their sporting prowess. As shown in Table 1, sportspeople who make it to the top of some sports earn extremely high incomes. For some, sporting success while young can also be translated into high incomes in later life either through sponsorship, public speaking or commentary positions. Many would question the fairness of a system that delivers huge incomes to a handful of elite sporting stars; but that is how the sports market works. However, there are good grounds for taking action to recover some of the publicly funded costs of training sportspeople who go on to earn very high incomes. In order to address this issue it is proposed that the Government introduce a HECS- type scheme whereby those sportspeople who go on to earn high incomes would be required to repay the costs incurred in the public provision of their training and development. -

Rapids Große Derbysieger

Jeden Dienstag neu | € 1,90 Nr. 16 | 17. April 2018 FOTOS: GEPA PICTURES 50 Wien ROSES NÄCHSTES ZIEL: FINALE! Das „Wunder von Salzburg“ 4 Seite SCHOBI & GOGO IM HOCH, AUSTRIA IN DER KRISE BAUMGARTNER IM INTERVIEW „Sind gefährlicher Cup-Underdog“ Seite 14 Rapids große TOTO RUNDE 16A 18-fach-Jackpot Derbysieger in der Torwette! Seite 6 Österreichische Post AG WZ 02Z030837 W – Sportzeitung Verlags-GmbH, Linke Wienzeile 40/2/22, 1060 Wien Retouren an PF 100, 13 Das Topspiel der Deutschen Bundesliga Borussia Dortmund – Bayer 04 Leverkusen Am Samstag ab 17.30 Uhr exklusiv auf Sky PR_AZ_Coverbalken_Sportzeitung_169x31_2018_V01.indd 1 12.04.18 09:29 Sportzeitung 02 16/2018 Anstoß Horst Hot & Not wunder gibt es immer wieder FUSSBALL Barometer EDITORIAL von Gerhard Weber Pedro Martins: Der Portugiese, Die Salzburger Bullen haben ihn also wirklich Doch die gehört jetzt Salzburg! Niemand redet zuletzt Guimarães, ist Nachfol- geschafft, den Sprung ins Europa League- momentan von Leipzig. Und das hat man ger von Oscar Garcia als Olym- Semifinale. Die großen Brüder aus Leipzig sich redlich verdient. Unglaublich, was piakos-Trainer nicht … Marco Rose und seine Schützlinge in den Ich gebe es zu – da kommt schon ein biss- letzten Wochen und Monaten geleistet ha- Akira Nishino: Zwei Monate vor chen Schadenfreude auf. Und das nicht nur, ben. Unglaublich, wie konsequent man in der WM löste Japans bisheriger weil es immer Spaß macht, wenn wir gegen- der Mozartstadt den Weg verfolgt hat Sportdirektor Vahid Halilhodzic über den Deutschen endlich wieder einmal Da gab‘s kein Jammern, da gab‘s Wehkla- als Teamchef ab die Nase vorne haben. -

Accolades Timely for Dragons First Toronto Test

D6 WEEKENDSPORT Saturday, March2, 2013 THE PRESS, Christchurch FOOTBALL Accolades timely for Dragons First Toronto test Tony Smith SQUADS Clapham, Darren White and Russell Kamo. for coach Nelsen Canterbury United got a confi- ‘‘They have a very strong ■ Canterbury United: Adam dence boost ahead of tomorrow’s collective, can defend well high or Fred Woodcock if Toronto start the season as they Highfield, Danny Knight (gks), national football league semifinals deep and they have momentums in finished the last, but for now he Dan Terris, Louie Bush, Tom with their coach and top scorer their games where they can hold Ryan Nelsen wouldn’t mind appears relaxed and content. Schwarz, Julyan Collett, Nick winning major awards. possession really well, they are a another five or six weeks of pre- His major challenge has been Wortelboer, Darren White, Aaron All White Aaron Clapham won very competitive team,’’ Tribulietx season himself but he’s declared coming to terms with salary caps. Clapham, Josh Smith, Andy the February player of the month told the premiership’s website. his Toronto FC players ready for ‘‘That’s probably the one thing I Barton, Chris Murphy, Ken award and Keith Braithwaite Canterbury tried to play a their Major League Soccer season was most inexperienced in, look- Yamamoto, Russell Kamo, Ash picked up his second coach of the pressing game high up the pitch opener in Vancouver tomorrow ing at Toronto’s salary cap and Wellbourn, Nathan Knox. month accolade of the season. against Auckland in their last (NZT). how it’s been handled,’’ he said. ■ Auckland City: Tamati Williams Four Canterbury Dragons — encounter and scored the opening The former All Whites captain ‘‘I have found it interesting and (gk), Simon Arms, Takuya Iwata, Clapham, goalkeeper Adam High- goal. -

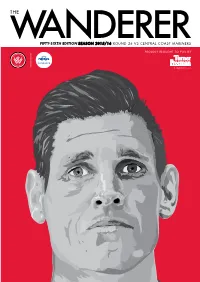

View Now Issue 56

FIFTY-SIXTH EDITION SEASON 2015/16 ROUND 26 VS CENTRAL COAST MARINERS PROUDLY BROUGHT TO YOU BY CONTENTS ThIS MATch WE'VE PACKED THIS ISSUE OF THE WANDERER WITH EVERYTHING YOU NEED FOR TONIGHT'S MATCH FEATURES FIFTY-SIXTH EDITION SEASON 2015/16 ROUND 26 VS CENTRAL COAST MARINERS PROUDLY BROUGHT TO YOU BY ThE WANDERER The views in this publication FAREWELL TO WANDERLAND 8 A FORGOTTEN RIVALRY 18 are not necessarily the views of The end of an era A look back on tonight’s fixture the NRMA Insurance Western Story by Jacob Windon Story by Domenic Trimboli Sydney Wanderers FC. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may only be reproduced with the written permission from the Club. REGULAR COLUMNS ADVERTISING OPEN LETTER: FOUNDATION FOX FOOTBALL FIX 20 GUARDIAN FUNERALS For all advertising enquiries in The Wanderer or questions PLAYER MARK BRIDGE 5 WANDERCREW MEMBERS ANTH'S SPOT THE OF THE WEEK: OUR HALF- about partnership with WARM UP 6 DIFFERENCE 22 TIME PARTICIPANTS 26 the club please contact the Corporate Partnerships team FIVE THINGS 11 CORPORATE NEWS: A [email protected]. HOME LOAN ALTERNATIVE PLAYERS TO WATCH: IN THE COMMUNITY: PHOTOGRAPHY FOR WESTERN SYDNEY ENTER YOUR SCHOOL All photography courtesy REDDY VS IZZO 13 BORROWERS 23 IN THE WANDERERS of Ali Erhan, Beans & SCHOOLS CUP 27 Mash Photography, Daniel FOX FOOTBALL FOCUS TAKE FIVE WITH Boud, Getty Images WITH ADAM PEACOCK 15 JONATHAN Parramatta Melita Eagles and Steve Christo. TODAY'S MATCH 16 ASPROPOTAMITIS 25 OUR PARTNERS 30 STAY CONNECTED VISIT WANDERLAND.COM.AU 3 OpEN LETTER FROM THE FOUNDATION PLAYER MARK BRIDGE THE LOCAL BOY REFLECTS ON HIS FAVOURITE MOMENTS AT WANDERLAND T’S GOING TO be a strange leaving Wanderland. -

INSIDE THIS ISSUE MARK BRIDGE: ONE YEAR on Topor- Stanley Vs Jeronimo SANTA's in TOWN GET to KNOW MARTY Lo Wander Women Are Back

SEVENTEENTH EdiTioN • SEaSoN 2013/14 VS ADELAIDE UNITED INSIDE THIS ISSUE MARK BRIDGE: ONE YEAR ON TOPOR- STANLEY VS JERONIMO SANTA'S IN TOWN GET TO KNOW MARTY LO WANDER WOMEN ARE BACK PROUDLY BROUGHT TO YOU BY 03 THIS WEEK ... 05 FROM THE CHAIRMAN 23 WELCOME UWS a message from Lyall Gorman. Wanderers welcome our newest corporate partner. 07 NEWS AND VIEWS 25 GeTTING TO KNOW MARTY LO RBB raise funds for the victims of Get to know our stars of the future and current the recent bush fires in NSW. Foxtel National Youth League players. 08 MARK BRIDGE: ONE YEAR ON 26 SPOT THE DIFFERENCE Celebrate Bridgey's momentous goal. Can you spot the five differences this week? 13 PLAYERS TO waTCH 27 WANDER WOMEN ARE BACK Nikolai Topor-Stanley and Jeronimo The Westfield W-League is about to kick Neumann head-to-head. off and check out our new look team ready to challenge for the title. 14 SANTA'S IN TOWN Look back at Santa's super goal. 28 #WanderTweeT What you wore to the Sydney derby last weekend. 16 TODAY'S MATCH Brought to you by amart Sports. The views in this publication are not necessarily the views 19 ROUND REVIEWS of the NRMA Insurance Western Sydney Wanderers FC. Material in this publication is copyrighted and may only Catch up on our latest results. be reproduced with the written permission of the NRMA 20 BEAUCHAMP’S CENTURY Insurance Western Sydney Wanderers FC. All photography courtesy of Getty Images, efsco media and Quarrie Sports A REAL CAPTAIN'S KNOCK Photography. -

2007 Annual Report

FFV 2007 Annual Report 1. Structure 2007 Annual Report 1. Structure 1.1 FFV VIPS FFV BOARD OF DIRECTORS PRESIDENT Tony Dunkerely Tony’s professional background includes board experience, both as Director and Chair of various professional and international committees and life membership to a range of sporting institutions. Tony has also enjoyed global business experience across Asia and Europe; experience in the research, development and implementation of a range of business strategies and plans aligned with quality, safety and benchmarking practices. Tony has signifi cant em- ployee relations experience; together with sound fi nancial acumen and management, particularly in the fi eld of return on investment and customer service. Through out his time in football, Tony has coached extensively through out the sport, including at the state team level. DIRECTORS Chris Nikou Chris Nikou has been involved in football for over 30 years observing and engaging the issues that affect the various stakeholders that comprise football in Victoria. Chris has played both junior and senior football in the state league and been involved at club level as Secretary and President. He is also a former member of the Appeals Board Tribunal and has since December 2003 been a Director of FFV. Chris is currently a Senior Partner at national law fi rm Middletons. He is the National Head of Corporate and Commercial and specialises in franchising law, mergers and acquisitions. Mark Trajcevski Mark is a Director at a global professional services fi rm specialising in risk management, governance, board effectiveness, fi nancial management and audit. Mark has formerly held the position of Honorary Treasurer. -

Andreas Ivanschitz

Plzeň: plavky místo deštníků 24 Tradiční kolaps Arsenalu 34 Česká dvacítka mezi elitou 58 JIŘÍ MÜLLER „Zájem měl i Haag, Nottingham Forest či Aston Villa. Ale když se objevila na scéně Legia Varšava, nebylo už co řešit,“ říká o hostování Tomáše Necida jeho agent Jiří Müller. FOTBALOVÝ TÝDENÍK | 50. ROČNÍK | VYCHÁZÍ V ÚTERÝ 7. 2. 2017 | 6/2017 ANDREAS IVANSCHITZ „Jsem dobrodruh!“ Zimní přestupy: Anglie poprvé v plusu 6/2017 AKTUÁLNĚ Úterý 7.2.2017 3 OBSAH Můj týden Jiří Müller: „Když se ozvala Legia, nebylo co řešit!“ ............. 4 Aktuálně Milionové bonusy za EURO ..................................................... 8 Rozhovor Andreas Ivanschitz: „Jsem dobrodruh, rád poznávám cizí země!“ ........... 12 Vážení čtenáři! Přestupové okno ve většině evropských lig skončilo. Přineslo jedno překvapení. Určitě jím nebyl fakt, že nejvíce peněz za posily tradičně „vy- házely“ kluby anglické Premier League, ale to, že poprvé ve své historii skončila nejslavnější fotba- lová liga nejen starého kontinentu v plusu. Může za to i maličkost: finanční šílenství čínských klubů, které utrácely jako o život. Vždyť z deseti nejná- kladnějších transferů této zimy jich mají na svě- domí Číňané hned čtyři a všem vévodí přestup Brazilce Oscara z Chelsea do šanghajského týmu SIPG za 60 milionů eur. Do Plzně přišla největší posila naopak zadarmo. Rakouskému špílma- chrovi Andreasi Ivanschitzovi vypršela smlouva v Seattlu a tento světoběžník se rozhodl vyslyšet návrhy slečny Viktorie a zamířil do své páté fotba- Reportáž Plzeň vyměnila pláštěnky za plavky .................................... 24 lové země. Ve Španělsku pak Gólu ochotně poskytl Aktuálně Zimní přestupy: Anglie poprvé v plusu! ............................... 30 rozhovor, v němž prozradí, nejen proč se vypravil Premier League Tradiční kolaps Arsenalu ........................................ -

Glory Days Official Matchday Programme Hyundai A-League 2019/20 Season, Round 7 Saturday 23 November, 2019 | 6:45Pm Ko | Hbf Park Perth Glory V Sydney Fc

GLORY DAYS OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME HYUNDAI A-LEAGUE 2019/20 SEASON, ROUND 7 SATURDAY 23 NOVEMBER, 2019 | 6:45PM KO | HBF PARK PERTH GLORY V SYDNEY FC MATCHDAY SPONSOR CHAIRMAN’S MEET THE COLUMN HEAD COACH: HEAD COACH: OPPOSITION TONY POPOVIC STEVE CORICA PLD SCD SUB PLD SCD SUB 1 Tando VELAPHI (GK) 1 Andrew REDMAYNE (GK) 2 Alex GRANT 2 Patrick FLOTTMANN 3 Jacob TRATT 3 Ben WARLAND Tony Sage 4 Gregory WÜTHRICH 4 Alex WILKINSON (C) Steve Corica 5 Ivan FRANJIC 5 Alexander BAUMJOHANN Firstly, I would like to Sydney FC arrive at HBF congratulate Sam Kerr 6 Dino DJULBIC 6 Ryan McGOWAN Park this evening having on signing for Chelsea. won four of their five 7 Joel CHIANESE 7 Michael ZULLO games thus far this term. She has been outstanding on and off 8 James MEREDITH 8 Paulo RETRE Head Coach Steve the pitch for the past Corica has retained five seasons and I am 9 Bruno FORNAROLI 9 Adam LE FONDRE the core of the squad sure that she will be 12 Kim SOO-BEOM 10 Milos NINKOVIC that defeated Glory as much of a star in in last season’s Grand the English Women’s 13 Osama MALIK 11 Kosta BARBAROUSES Final, while adding a Premier League as she number of high-quality has been in the Westfield 14 Chris HAROLD 12 Trent BUHAGIAR new recruits including W-League and America’s Socceroos defender NWSL. 15 Brandon WILSON 13 Brandon O’NEILL Ryan McGowan, ex-Western Sydney Moving on to tonight, 16 Tomislav MRCELA 16 Joel KING Wanderers midfielder this Premiers v Alexander Baumjohann Champions clash is one 17 Diego CASTRO (C) 17 Anthony CACERES and livewire New that we have all been 18 Nick D'AGOSTINO 18 Luke IVANOVIC Zealand striker, Kosta looking forward to and Barbarouses. -

Sir Peter Leitch Club at MT SMART STADIUM, HOME of the MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS

Sir Peter Leitch Club AT MT SMART STADIUM, HOME OF THE MIGHTY VODAFONE WARRIORS 16th August 2017 Newsletter #183 Awesome Loyal Fans Supporting the Boys Last Sunday! For Sale: One Used League Club, Average Condition By David Kemeys Former Sunday Star-Times Editor, Former Editor-in-Chief Suburban Newspapers, Long Suffering Warriors Fan O AUCKLAND businessman Paul Davys is in talks with our owner Eric Watson about buying the club, Salthough Watson says he’s in no hurry. He’s had a stake for 17 years, so full marks for persistence, and what’s another year. Watson might be in no hurry, Davys is, saying he’ll give Watson until Friday because he needs to know one way or the other, or he'll walk away. “If he hasn't by the end of the week then it's probably better for the club and me to move on.” Davys has a chunk of the childcare company ChoiceKids, which is as far – or almost identical, depending on your viewpoint – from league as it is possible to get. Doesn’t seem to worry Davys, who says he wants to be hands on, and he is one of the many convinced the culture is wrong, and that attitudes have to improve. “There's a culture problem, fan scan see it, the coaching staff can see it, and the players can see it. But it's hard to change if you don't know how. I've got a fair idea and a fair amount of knowledge on how to build a cul- ture, so that's what I can bring.” No shortage of confidence then. -

Diplomarbeit

Diplomarbeit Titel der Diplomarbeit „Mythos Rapid - Fankommunikation und kollektives Gedächtnis im modernen Fußball“ Verfasser Martin Hell angestrebter akademischer Grad Magister der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, im Juli 2009 Matrikelnummer: 0001299 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A301 300 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Publizistik- und Kommunikationswissenschaft Betreuer: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Peter Vitouch Danksagung Ich danke allen Menschen, die ich kennen lernen durfte und mich in meinem Leben beeinflusst haben. Es liegt an uns Fans dass zu bewahren, was Rapid wirklich ausmacht: TRADITION, KAMPFGEIST & LEIDENSCHAFT! (GO WEST, Fanzine der UR – 1/08, vom 27.2.2008) Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................................................1 2 Themenabgrenzung .................................................................................................................4 2.1 Das System des modernen Fußballs .................................................................................4 2.2 Der Fan .............................................................................................................................6 2.3 Rassismus und Gewalt......................................................................................................8 3 Gruppensoziologie.................................................................................................................11 3.1 Die Gruppe – Definition und Klassifikation ..................................................................11 -

FFA-Cup-2019 Competition-Guide

1 FFA Cup 2019 Competition Guide CONTENTS Page Information, fixtures, results 2 Clubs 5 History and records 25 FFA CUP Web: www.theffacup.com.au Facebook: facebook.com/ffacup Twitter: @FFACup The FFA Cup is a national knockout competition run by Football Federation Australia (FFA) in conjunction with the State and Territory Member Federations. A total of 737 clubs entered the FFA Cup 2019, a number that has significantly grown from the first edition of the FFA Cup in 2014, when 617 clubs entered. The FFA Cup 2019 started in February with the Preliminary Rounds to determine the 21 clubs from the semi-professional and amateur tiers. These clubs joined ten of the Hyundai A-League clubs (Western United FC will not participate in this edition) and the reigning National Premier Leagues Champions (Campbelltown City SC) in the Final Rounds. The FFA Cup Final 2019 will be played on Wednesday 23 October with the host city to be determined by a live draw. Each cup tie must be decided on the day, with extra time to decide results of matches drawn after 90 minutes, followed by penalties if required. At least one Member Federation club is guaranteed to progress to the Semi Finals. Previous winners of the FFA Cup are Adelaide United (2014 and 2018), Melbourne Victory (2015), Melbourne City FC (2016) and Sydney FC (2017). Broadcast partners – FOX SPORTS FOX SPORTS will again provide comprehensive coverage of the FFA Cup 2019 Final Rounds. The FFA Cup’s official broadcaster will show one LIVE match per match night from the Round of 32 onwards, while providing coverage and updates, as well as live streams, of non-broadcast matches.