Description of a New Grouse from Southern California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Breeding Birds of Four Isolated Mountains in Southern California

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 24, Number 4, 1993 BREEDING BIRDS OF FOUR ISOLATED MOUNTAINS IN SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA JOAN EASTON LENTZ, 433 PimientoLn., Santa Barbara,California 93108 The breedingavifaunas of FigueroaMountain and Big PineMountain in SantaBarbara County and Pine Mountain and Mount Pinos in Venturaand Kern countiesare of great ornithologicalinterest. These four mountains supportislands of coniferousforest separated by otherhabitats at lower elevations. Little information on the birds of the first three has been publishedpreviously. From 1981 to 1993, I, withthe helpof a numberof observers,censused the summer residentbirds of these four mountains,paying particular attentionto the speciesrestricted to highelevations. By comparingthese avifaunaswith each other, as well as with those of the San Gabriel,San Bernardino,and San Jacinto mountains, and the southernSierra Nevada, I hopeto addto currentknowledge of thestatus and distribution of montane birds in southern California. VEGETATIO51AND GEOGRAPHY The patternof vegetationin the surveyareas is typicalof thatfound on manysouthern California mountains. Generally, the south- and west-facing slopesof the mountainsare coveredwith chaparralor pinyon-juniper woodlandalmost to the summits.On the north-facingslopes, however, coolertemperatures and more mesic conditions support coniferous forest, which often reaches far down the mountainsides. Because the climate is arid, few creeksor streamsflow at high elevations,and most water is availablein the form of seepsor smallsprings. BothFigueroa (4528 feet, 1380 m) andBig Pine (6828 feet,2081 m) mountainsare locatedin the San RafaelRange, the southernmostof the CoastRanges (Figure 1, Norrisand Webb 1990). The San RafaelMoun- tainsare borderedby the SierraMadre, a low chaparral-coveredrange, to the northand the CuyamaValley to the northeast.The SisquocRiver drains west from the San Rafael Mountains and Sierra Madre to the Santa Maria River.To the southlies the foothillgrassland of the SantaYnez Valley. -

Deer Book Part 7 6/29/00 10:09 AM Page 1

Deer Book part 7 6/29/00 10:09 AM Page 1 81 The old adage “you can’t judge a book by its cover” holds true for the value of desert habitats to mule deer. While deer densities are low in the Southern Desert bioregion, some of the largest bucks in the state are taken each year in these arid environments. Photo by Mark Hoshovsky H. Southern Desert 1. Deer Habitats and Ecology The Mojave and Sonoran deserts of California support some of our driest and hottest habitats in the state. It comes as no surprise, then, that these areas support some of our lowest deer densities. The deer that inhabit our southern deserts are also the least understood ecologically in California. These animals, while not migratory like those in the Sierra Nevada, do move long distances in response to changes in the availability of water and forage. Summer rains in the desert cause the germination of annual grasses and forbs, and deer will move to take advantage of this forage. Desert washes and the vegetation in them are especially important for providing cover and food, and free-standing water in the summer seems to be essential for maintaining burro mule deer. Deer Book part 7 6/29/00 10:09 AM Page 2 82 A SPORTSMAN’S GUIDE TO IMPROVING DEER HABITAT IN CALIFORNIA 2. Limiting or Important Habitat Factors The availability of free-standing water in the summer in areas with other- wise appropriate vegetation is thought to be the most important habitat fac- tor for mule deer in most of our southern deserts. -

Region of the San Andreas Fault, Western Transverse Ranges, California

Thrust-Induced Collapse of Mountains— An Example from the “Big Bend” Region of the San Andreas Fault, Western Transverse Ranges, California By Karl S. Kellogg Scientific Investigations Report 2004–5206 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2004 For sale by U.S. Geological Survey, Information Services Box 25286, Denver Federal Center Denver, CO 80225 For more information about the USGS and its products: Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. iii Contents Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Introduction …………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Geology of the Mount Pinos and Frazier Mountain Region …………………………………… 3 Fracturing of Crystalline Rocks in the Hanging Wall of Thrusts ……………………………… 5 Worldwide Examples of Gravitational Collapse ……………………………………………… 6 A Spreading Model for Mount Pinos and Frazier Mountain ………………………………… 6 Conclusions …………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………… 8 References …………………………………………………………………………………… 8 Illustrations 1. Regional geologic map of the western Transverse Ranges of southern California …………………………………………………………………………… 2 2. Simplified geologic map of the Mount Pinos-Frazier Mountain region …………… 2 3. View looking southeast across the San Andreas rift valley toward Frazier Mountain …………………………………………………………………… 3 4. View to the northwest of Mount Pinos, the rift valley (Cuddy Valley) of the San Andreas fault, and the trace of the Lockwood Valley fault ……………… 3 5. -

Vascular Flora of the Liebre Mountains, Western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 18 | Issue 2 Article 15 1999 Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California Steve Boyd Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Boyd, Steve (1999) "Vascular flora of the Liebre Mountains, western Transverse Ranges, California," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 18: Iss. 2, Article 15. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol18/iss2/15 Aliso, 18(2), pp. 93-139 © 1999, by The Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden, Claremont, CA 91711-3157 VASCULAR FLORA OF THE LIEBRE MOUNTAINS, WESTERN TRANSVERSE RANGES, CALIFORNIA STEVE BOYD Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden 1500 N. College Avenue Claremont, Calif. 91711 ABSTRACT The Liebre Mountains form a discrete unit of the Transverse Ranges of southern California. Geo graphically, the range is transitional to the San Gabriel Mountains, Inner Coast Ranges, Tehachapi Mountains, and Mojave Desert. A total of 1010 vascular plant taxa was recorded from the range, representing 104 families and 400 genera. The ratio of native vs. nonnative elements of the flora is 4:1, similar to that documented in other areas of cismontane southern California. The range is note worthy for the diversity of Quercus and oak-dominated vegetation. A total of 32 sensitive plant taxa (rare, threatened or endangered) was recorded from the range. Key words: Liebre Mountains, Transverse Ranges, southern California, flora, sensitive plants. INTRODUCTION belt and Peirson's (1935) handbook of trees and shrubs. Published documentation of the San Bernar The Transverse Ranges are one of southern Califor dino Mountains is little better, limited to Parish's nia's most prominent physiographic features. -

Mount Pinos Forest Health Project Proposal

Mount Pinos Forest Health Project Los Padres National Forest Mount Pinos Forest Health Project Proposal Introduction The Los Padres National Forest proposes to implement a Forest Health project in the Mount Pinos area on the Mount Pinos Ranger District. The project area encompasses approximately 1,682 acres on the eastside shoulder of Mount Pinos between the Cuddy and Lockwood Valleys. The project area is located in both Ventura and Kern Counties, California (figure 1). The Mount Pinos Forest Health Project area lies within an Insect and Disease Treatment Designation Area1 where declining forest health conditions put the area at risk for substantial tree mortality. The purpose of this project is to reduce existing stand densities and alter stand structure and species composition to create landscapes more resilient to impacts of drought, insects, and disease.2 Figure 1. Mount Pinos Forest Health Project vicinity map This project would improve forest health by reducing existing stand densities and the risk of tree mortality through the removal or on-site treatment of small-diameter, less than 24-inch and dead trees from overstocked stands. Treatments would consist of either mechanical and/or manual thinning methods. 1 https://www.fs.usda.gov/managing-land/farm-bill/area-designations 2References are available at: www.fs.usda.gov/main/lpnf/landmanagement/planning or are on file at the Mt. Pinos Ranger District in Frazier Park, California. 1 Mount Pinos Forest Health Project Los Padres National Forest Prescribed fire and pile burning would be used as needed. The proposed treatments would also benefit fire and fuels management by reducing surface, ladder, and crown fuels. -

Buy This Book

Excerpted from buy this book © by the Regents of the University of California. Not to be reproduced without publisher’s written permission. INTRODUCTION This book is an attempt to present to general readers not Panamint Range, because for the most part the wildflower trained in taxonomic botany, but interested in nature and seeker does not travel in the desert in summer. their surroundings, some of the wildflowers of the California mountains in such a way that they can be identified without technical knowledge. Naturally, these are mostly summer The California Mountains wildflowers, together with a few of the more striking species that bloom in spring and fall. They are roughly those from the In general, the mountains of California consist of two great yellow pine belt upward through the red fir and subalpine series of ranges: an outer, the Coast Ranges; and an inner, the forests to the peaks above timberline. Obviously, the 286 Sierra Nevada and the southern end of the Cascade Range, in- plants presented cannot begin to cover all that occur in so cluding Lassen Peak and Mount Shasta.The Sierra Nevada,an great an altitudinal range, especially when the geographical immense granitic block 400 miles long and 50 to 80 miles limits of the pine belt are considered. wide, extends from Plumas County to Kern County. It is no- Mention of the pine belt in California mountains will nat- table for its display of cirques, moraines, lakes, and glacial val- urally cause you to think of the Sierra Nevada, but of course leys and has its highest point at Mount Whitney at 14,495 feet this belt also extends into the southern Cascade Range (Mount above sea level. -

Transverse Ranges - Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

San Gabriel Mountains - Field Trip http://www.csun.edu/science/geoscience/fieldtrips/san-gabriel-mts/index.html Sourcebook Home Biology Chemistry Physics Geoscience Reference Search CSUN San Gabriel Mountains - Field Trip Science Teaching Series Geography & Topography The Sourcebook for Teaching Science Hands-On Physics Activities Tour - The route of the field trip Hands-On Chemistry Activities GPS Activity HIstory of the San Gabriels Photos of field trip Internet Resources Geology of the San Gabriel Mountains I. Developing Scientific Literacy 1 - Building a Scientific Vocabulary Plate Tectonics, Faults, Earthquakes 2 - Developing Science Reading Skills 3 - Developing Science Writing Skills Rocks, Minerals, Geological Features 4 - Science, Technology & Society Big Tujunga Canyon Faults of Southern California II. Developing Scientific Reasoning Gneiss | Schist | Granite | Quartz 5 - Employing Scientific Methods 6 - Developing Scientific Reasoning Ecology of the San Gabriel Mountains 7 - Thinking Critically & Misconceptions Plant communities III. Developing Scientific Animal communities Understanding Fire in the San Gabriel Mountains 8 - Organizing Science Information Human impact 9 - Graphic Oganizers for Science 10 - Learning Science with Analogies 11 - Improving Memory in Science Meteorology, Climate & Weather 12 - Structure and Function in Science 13 - Games for Learning Science Inversion Layer Los Angeles air pollution. Åir Now - EPA reports. IV. Developing Scientific Problem Climate Solving Southern Calfirornia Climate 14 - Science Word Problems United States Air Quality blog 15 - Geometric Principles in Science 16 - Visualizing Problems in Science 1 of 2 7/14/08 12:56 PM San Gabriel Mountains - Field Trip http://www.csun.edu/science/geoscience/fieldtrips/san-gabriel-mts/index.html 17 - Dimensional Analysis Astronomy 18 - Stoichiometry 100 inch Mount Wilson telescope V. -

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation As Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest

Rationales for Animal Species Considered for Designation as Species of Conservation Concern Inyo National Forest Prepared by: Wildlife Biologists and Natural Resources Specialist Regional Office, Inyo National Forest, and Washington Office Enterprise Program for: Inyo National Forest August 2018 1 In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. -

Insights from Lowtemperature Thermochronometry Into

TECTONICS, VOL. 32, 1602–1622, doi:10.1002/2013TC003377, 2013 Insights from low-temperature thermochronometry into transpressional deformation and crustal exhumation along the San Andreas fault in the western Transverse Ranges, California Nathan A. Niemi,1 Jamie T. Buscher,2 James A. Spotila,3 Martha A. House,4 and Shari A. Kelley 5 Received 21 May 2013; revised 21 October 2013; accepted 28 October 2013; published 20 December 2013. [1] The San Emigdio Mountains are an example of an archetypical, transpressional structural system, bounded to the south by the San Andreas strike-slip fault, and to the north by the active Wheeler Ridge thrust. Apatite (U-Th)/He and apatite and zircon fission track ages were obtained along transects across the range and from wells in and to the north of the range. Apatite (U-Th)/He ages are 4–6 Ma adjacent to the San Andreas fault, and both (U-Th)/He and fission track ages grow older with distance to the north from the San Andreas. The young ages north of the San Andreas fault contrast with early Miocene (U-Th)/He ages from Mount Pinos on the south side of the fault. Restoration of sample paleodepths in the San Emigdio Mountains using a regional unconformity at the base of the Eocene Tejon Formation indicates that the San Emigdio Mountains represent a crustal fragment that has been exhumed more than 5 km along the San Andreas fault since late Miocene time. Marked differences in the timing and rate of exhumation between the northern and southern sides of the San Andreas fault are difficult to reconcile with existing structural models of the western Transverse Ranges as a thin-skinned thrust system. -

Download Index

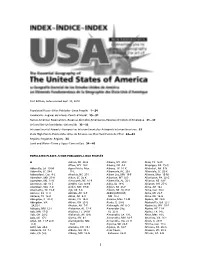

First Edition, Index revised Sept. 23, 2010 Populated Places~Sitios Poblados~Lieux Peuplés 1—24 Landmarks~Lugares de Interés~Points d’Intérêt 25—31 Native American Reservations~Reservas de Indios Americanos~Réserves d’Indiens d’Améreque 31—32 Universities~Universidades~Universités 32—33 Intercontinental Airports~Aeropuertos Intercontinentales~Aéroports Intercontinentaux 33 State High Points~Puntos Mas Altos de Estados~Les Plus Haut Points de l’État 33—34 Regions~Regiones~Régions 34 Land and Water~Tierra y Agua~Terre et Eau 34—40 POPULATED PLACES~SITIOS POBLADOS~LIEUX PEUPLÉS A Adrian, MI 23-G Albany, NY 29-F Alice, TX 16-N Afton, WY 10-F Albany, OR 4-E Aliquippa, PA 25-G Abbeville, LA 19-M Agua Prieta, Mex Albany, TX 16-K Allakaket, AK 9-N Abbeville, SC 24-J 11-L Albemarle, NC 25-J Allendale, SC 25-K Abbotsford, Can 4-C Ahoskie, NC 27-I Albert Lea, MN 19-F Allende, Mex 15-M Aberdeen, MD 27-H Aiken, SC 25-K Alberton, MT 8-D Allentown, PA 28-G Aberdeen, MS 21-K Ainsworth, NE 16-F Albertville, AL 22-J Alliance, NE 14-F Aberdeen, SD 16-E Airdrie, Can 8,9-B Albia, IA 19-G Alliance, OH 25-G Aberdeen, WA 4-D Aitkin, MN 19-D Albion, MI 23-F Alma, AR 18-J Abernathy, TX 15-K Ajo, AZ 9-K Albion, NE 16,17-G Alma, Can 30-C Abilene, KS 17-H Akhiok, AK 9-P ALBUQUERQUE, Alma, MI 23-F Abilene, TX 16-K Akiak, AK 8-O NM 12-J Alma, NE 16-G Abingdon, IL 20-G Akron, CO 14-G Aldama, Mex 13-M Alpena, MI 24-E Abingdon, VA Akron, OH 25-G Aledo, IL 20-G Alpharetta, GA 23-J 24,25-I Akutan, AK 7-P Aleknagik, AK 8-O Alpine Jct, WY 10-F Abiquiu, NM 12-I Alabaster, -

75. Sawmill Mountain (Parikh 1993B) Location the Sawmill Mountain Recommended Research Natural Area Is on Los Padres National Forest in N

75. Sawmill Mountain (Parikh 1993b) Location The Sawmill Mountain recommended Research Natural Area is on Los Padres National Forest in N. Ventura and S. Kern counties. It lies immediately W. of Mount Pinos, SE. of Cerro Noroeste (Mount Abel), just W. of San Emigdio Mesa, and occupies parts of sects. 25 and 36 T9N, R22W; sects. 30 and 31 T9N, R21W; sects. 1, 2, 11, 12, 13, and 14 T8N, R22W; and sects. 7 and 17 T8N, R21W MDBM (38°48'N., 119°10'W.), USGS Sawmill Mountain quad (fig. 151). Ecological subsection – Northern Transverse Ranges (M262Bb). Target Element Jeffrey Pine (Pinus jeffreyi) Forest Distinctive Features The flora here is mainly derived from the Sierran forest of the West American element of the Arcto-Tertiary geoflora. The pine belt in S. California is similar to the S. Sierra Nevada: many of the high-elevation, montane species with disjunct distributions have affinities with the Sierran flora. Many other species present here are transitional between drier, interior desert flora and montane flora from wetter, cooler regions. Figure 151— Rare Plants: Monardella linoides ssp. oblonga is on CNPS List 1B; Delphinium parishii Sawmill Mountain ssp. purpureum (D. parryii ssp. purpureum in Hickman [1993]), Frasera neglecta rRNA (Swertia n. in Hickman [1993]), and Lupinus elatus are all on CNPS List 4. Rare Fauna: The region is a part of the breeding habitat of the Federally- and State-listed endangered species California condor (Gymnogyps californianus). Physical Characteristics The area encompasses about 3800 acres (1539 ha). Elevations range from 6250 feet to 8750 feet (1905-2667 m) at the summit of Sawmill Mountain. -

Species Accounts -- Animals

SoCal Biodiversity - Animals Arboreal Salamander Amphibian SoCal Biodiversity - Animals Arboreal Salamander Amphibian Arroyo Toad Arboreal Salamander Arboreal Salamander (Aneides lugubris) Management Status Heritage Status Rank: G5N5S4 Federal: None State: None Other: Species identified as a local viability concern (Stephenson and Calcarone 1999) General Distribution Arboreal salamander occurs in yellow pine and black oak forests in the Sierra Nevada, and in coastal live oak woodlands from northern California to Baja California. The species also occurs in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada from El Dorado County to Madera County and on South Farallon, Santa Catalina, Los Coronados, and Ano Nuevo islands off the coast of California (Petranka 1998, Stebbins 1951, Stebbins 1985). Arboreal salamander occurs from sea level to an elevation of about 5,000 feet (1,520 meters) (Stebbins 1985). Distribution in the Planning Area Arboreal salamander reportedly occurs in the foothills and lower elevations of every mountain range on National Forest System lands, although it is seldom seen (Stephenson and Calcarone 1999). There are records of occurrence for this species on the Los Padres National Forest near upper San Juan Creek and on the Cleveland National Forest near Soldier Creek (USDA Forest Service file information), San Gabriel foothills east to Day Canyon, and in the San Jacinto Mountains (Goodward pers. comm.). Systematics There are four species in the genus Aneides in the western United States, three of which occur in California (Stebbins 1985). Of these three, only arboreal salamander ranges into southern California. Most of the Aneides salamanders climb (Stebbins 1985). Arboreal salamander consists of two chromosomally differentiated groups that intergrade in south and east-central Mendocino County, about 56 miles (90 kilometers) north of the San Francisco Bay region (Sessions and Kezer 1987).