Herb Pomeroy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JAZZ WORTH READING: “THE BOSTON JAZZ CHRONICLES: FACES, PLACES and NIGHTLIFE 1937-1962″ Posted on February 20, 2014

From Michael Steinman’s blog JAZZ LIVES MAY YOUR HAPPINESS INCREASE. Jazz: where "lives" is both noun and verb JAZZ WORTH READING: “THE BOSTON JAZZ CHRONICLES: FACES, PLACES AND NIGHTLIFE 1937-1962″ Posted on February 20, 2014 Some of my readers will already know about Richard Vacca’s superb book, published in 2012 by Troy Street Publishing. I first encountered his work in Tom Hustad’s splendid book on Ruby Braff, BORN TO PLAY. Vacca’s book is even better than I could have expected. Much of the literature about jazz, although not all, retells known stories, often with an ideological slant or a “new” interpretation. Thus it’s often difficult to find a book that presents new information in a balanced way. BOSTON JAZZ CHRONICLES is a model of what can be done. And you don’t have to be particularly interested in Boston, or, for that matter, jazz, to admire its many virtues. Vacca writes that the book grew out of his early idea of a walking tour of Boston jazz spots, but as he found out that this landscape had been obliterated (as has happened in New York City), he decided to write a history of the scene, choosing starting and ending points that made the book manageable. The book has much to offer several different audiences: a jazz- lover who wants to know the Boston history / anecdotal biography / reportage / topography of those years; someone with local pride in the recent past of his home city; someone who wishes to trace the paths of his favorite — and some obscure — jazz heroes and heroines. -

Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950S and Early 1960S New World NW 275

Introspection: Neglected Jazz Figures of the 1950s and early 1960s New World NW 275 In the contemporary world of platinum albums and music stations that have adopted limited programming (such as choosing from the Top Forty), even the most acclaimed jazz geniuses—the Armstrongs, Ellingtons, and Parkers—are neglected in terms of the amount of their music that gets heard. Acknowledgment by critics and historians works against neglect, of course, but is no guarantee that a musician will be heard either, just as a few records issued under someone’s name are not truly synonymous with attention. In this album we are concerned with musicians who have found it difficult—occasionally impossible—to record and publicly perform their own music. These six men, who by no means exhaust the legion of the neglected, are linked by the individuality and high quality of their conceptions, as well as by the tenaciousness of their struggle to maintain those conceptions in a world that at best has remained indifferent. Such perseverance in a hostile environment suggests the familiar melodramatic narrative of the suffering artist, and indeed these men have endured a disproportionate share of misfortunes and horrors. That four of the six are now dead indicates the severity of the struggle; the enduring strength of their music, however, is proof that none of these artists was ultimately defeated. Selecting the fifties and sixties as the focus for our investigation is hardly mandatory, for we might look back to earlier years and consider such players as Joe Smith (1902-1937), the supremely lyrical trumpeter who contributed so much to the music of Bessie Smith and Fletcher Henderson; or Dick Wilson (1911-1941), the promising tenor saxophonist featured with Andy Kirk’s Clouds of Joy; or Frankie Newton (1906-1954), whose unique muted-trumpet sound was overlooked during the swing era and whose leftist politics contributed to further neglect. -

SLINGERLAND a DRUMS Sommur!

has a Coleman Hawkins LP coming Jaki Byard quintet and big band... Strictly Ad Lib called Soul, with Hawk joined by Warren Covington’s Tommy Dorsey Kenny Burrell, Ray Bryant, Osie band may figure in a British band (Continued from page 8) Johnson, and Wendell Marshall. swap with a Cha-Cha-Cha band Bryant taught Hawk Greensleeves headed by Rico coming here . Wess . Willie (The Lion) Smith, for the date . Bob Corwin took Sidney Becht recovered from a re Sonny Terry, Zoot Sims, Sol Yaged, over the piano chair from Bill Trig cent illness. He had a bronchitis Candido, and Big Miller had guest lia with Anita O’Day . United attack in mid-fall . George Lewis Shots on the United Artists record Artists cut Martin Williams’ History is figuring in a possible swap for ing of the Living History of Jazz at of the Jazz Trumpet LP late in England, in conjunction with Lewis' the Apollo, with Herb Pomeroy’s December . Roy Haynes’ group, European tour this spring ... In band and narrator John McLellan. with Hank Mobley, Curtis Fuller, siders in the east point out that Symphony Sid reports he plans to Richard Wyandes, and Doug Wat Jack Lewis first cut Shorty Rogen take a septet to Europe in the spring kins, did a concert for the Orange and the early west coast sides, not for a Birdland tour, and hopes to County community college jazz club Bob York as carried in Los Angeles include Johnny Griffin, Lee Morgan, in mid-December. Ad Lib recently. Curtis Fuller, Pepper Adams, Tom Lou Donaldson signed with Blue Ed Thigpen is reported leaving my Flanagan, and Bud Powell . -

Spring Weekend Coming

®f)e Jleto i)amp§f)tre VOL. 52 ISSUE 21 UNIVERSITY OF NEW HAMPSHIRE, DURHAM, N. H. — FEBRUARY 28, 1963 TEN CENTS Advisers, Grades Tour-Guide Plan To Be Subject “I hope that the program will meet on-the-spot needs as well as those planned in ad vance,” said Ronald Barrett, Of Conference Director of the Memorial Un ion, about the proposed Tour Guides Program which was ap The faculty adviser problem selected because grades affect proved recently by the Univers and the grading system will be all students in the University. ity Trustees. It will provide a the topics of discussion at the Several improvements have central information c e n t er , Twelfth Annual Conference on been proposed to perfect the probably at the Union, for par Campus Affairs to be held in present grading system. The ents and other visitors and the Memorial Union this Satur Educational Research Commit have available student guides day, March 2. tee feels that an 8.0 system to show guests around the cam Sponsored by the Educational would be fairer to the student pus. Research Committee of the than the 4.0 system. The program which has been Student Senate, two representa With this system, the students in the planning for a year needs tives from each campus housing obtaining an 81 and an 89 would funds now to make it a reality, unit will attend. not both receive the same grade, according to Mr. Barrett. Stud The purpose of the annual but instead would receive a B- ents wishing to participate as conference is to provide students and a B-I-, respectively. -

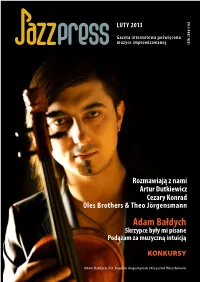

Jazzpress 0213

LUTY 2013 Gazeta internetowa poświęcona muzyce improwizowanej 2084-3143 ISSN Rozmawiają z nami Artur Dutkiewicz Cezary Konrad Oles Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann Adam Bałdych Skrzypce były mi pisane Podążam za muzyczną intuicją KONKURSY Adam Bałdych, fot. Bogdan Augustyniak i Krzysztof Wierzbowski SPIS TREŚCI 3 – Od Redakcji 40 – Publicystyka 40 Felieton muzyczny Macieja Nowotnego 4 – KONKURSY O tym, dlaczego ona tańczy NIE dla mnie... 6 – Co w RadioJAZZ.FM 42 Najciekawsze z najmniejszych w 2012 6 Jazz DO IT! 44 Claude Nobs 12 – Wydarzenia legendarny twórca Montreux Jazz Festival 46 Ravi Shankar 14 – Płyty Geniusz muzyki hinduskiej 14 RadioJAZZ.FM poleca 48 Trzeci nurt – definicja i opis (część 3) 16 Nowości płytowe 50 Lektury (nie tylko) jazzowe 22 Pod naszym patronatem Reflektorem na niebie wyświetlimy napis 52 – Wywiady Tranquillo 52 Adam Baldych 24 Recenzje Skrzypce były mi pisane Walter Norris & Leszek Możdżer Podążam za muzyczną intuicją – The Last Set Live at the a – Trane 68 Cezary Konrad W muzyce chodzi o emocje, a nie technikę 26 – Przewik koncertowy 77 Co słychać u Artura Dutkiewicza? 26 RadioJAZZ.FM i JazzPRESS zapraszają 79 Oles Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann 27 Koncerty w Polsce Transgression to znak, że wspięliśmy się na 28 Nasi zagranicą nowy poziom 31 Ulf Wakenius & AMC Trio 33 Oleś Brothers & Theo Jörgensmann tour 83 – BLUESOWY ZAUŁEK Obłędny klarnet w magicznym oświetleniu 83 29 International Blues Challenge 35 Extra Ball 2, czyli Śmietana – Olejniczak 84 Magda Piskorczyk Quartet 86 T-Bone Walker 37 Yasmin Levy w Palladium 90 – Kanon Jazzu 90 Kanon w eterze Music for K – Tomasz Stańko Quintet The Trio – Oscar Peterson, Joe Pass, Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen 95 – Sesje jazzowe 101 – Redakcja Możesz nas wesprzeć nr konta: 05 1020 1169 0000 8002 0138 6994 wpłata tytułem: Darowizna na działalność statutową Fundacji JazzPRESS, luty 2013 Od Redakcji Czas pędzi nieubłaganie i zaskakująco szybko. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1992

Kattl hlCL^WOOD I ? 7 2 W Toofc ofExcellence In every discipline, outstanding performance springs from the combination of skill, - vision and commitment. As a technology leader, GE Plastics is dedicated to the development of advanced materials: engineering thermoplastics, silicones, superabrasives and circuit board substrates. Like the lively arts that thrive in this inspiring environment, we enrich life's quality through creative excellence. GE Plastics -> Jazz At Tanglewood WM Friday, Saturday, and Sunday August 28, 29, and 30, 1992 Tanglewood, Lenox, Massachusetts '-•' Friday, August 28, at 7:30 p.m. THE MODERN JAZZ QUARTET RAY CHARLES Koussevitzky Music Shed Saturday, August 29 at 4 :30 p.m. CHRISTOPHER HOLLYDAY QUARTET REBECCA PARRIS and the GEORGE MASTERHAZY QUARTET Theatre-Concert Hall at 7:30 p.m. MAUREEN McGOVERN and MEL TORME with the HERB POMEROY BIG BAND Koussevitzky Music Shed Sunday, August 30 at 4 :30 p.m. GARY BURTON AND EDDIE DANIELS Theatre-Concert Hall at 7:30 p.m. DAVE BRUBECK QUARTET WYNTON MARSALIS Koussevitzky Music Shed ARTISTS The Modern Jazz Quartet Gibbs in the Woody Herman Second Herd. The following year he rejoined the Gillespie band, eventually becoming a founding member of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Among the many compositions Mr. Jackson contributed to the group, "Bags' Groove" has become a classic. During the members' annual vacation from the MJQ, Milt Jack- son assembles various groups of musicians to record albums under his own name and to play occasional engagements. Recently he returned to his bebop roots for an album aptly entitled Be Bop. Bass player Percy Heath was born in Making a return Tanglewood appearance, Wilmington, North Carolina, and grew up the Modern Jazz Quartet has a unique in Philadelphia. -

Charlie Mariano and the Birth of Boston Bop

Charlie Mariano and the Birth of Boston Bop By Richard Vacca The tributes to alto saxophonist Charlie Mariano that have appeared since his death on June 16, 2009 have called him an explorer, an innovator, and a musical adventurer. The expatriot Mariano was all of those things—a champion of world music before anyone thought to call it that. Mariano was known for the years he spent crisscrossing Europe and Asia, but his musical career began in Boston, the city where he was born. In the years between 1945 and 1953, he was already an explorer and innovator, but his most important role was as a leader and catalyst. He helped build the founda- tion of modern jazz in Boston on three fronts: as soloist in the Nat Pierce Orchestra of the late 1940s, as a bandleader cutting the records that introduced Boston’s modern jazz talent to a wider world in the early 1950s, and as the founder of the original Jazz Workshop in 1953. Born in 1923, Mariano grew up in Boston’s Hyde Park district in a house filled with music. His father loved opera, his sister played piano, and starting in his late teens, Charlie himself played the alto saxo- phone, the instrument for which he was best known throughout his life. By 1942, Mariano was already making the rounds on Boston’s buckets of blood circuit. The following year he was drafted. It was Mariano’s good fortune to spend his two years in service playing in an Army Air Corps band, and while stationed in California, he heard Charlie Parker for the first time. -

Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Nov 2005 Vol. 21, No. 11 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Earshot Jazz Festival in November, P 4 Conversation with Randy Halberstadt, P 21 Ballard Jazz Festival Preview, P 23 Gary McFarland Revived on Film, P 25 PHOTO BY DANIEL SHEEHAN EARSHOT JAZZ A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community ROCKRGRL Music Conference Executive Director: John Gilbreath Earshot Jazz Editor: Todd Matthews Th e ROCKRGRL Music Conference Highlights of the 2005 conference Editor-at-Large: Peter Monaghan 2005, a weekend symposium of women include keynote addresses by Patti Smith Contributing Writers: Todd Matthews, working in all aspects of the music indus- and Johnette Napolitano; and a Shop Peter Monaghan, Lloyd Peterson try, will take place November 10-12 at Talk Q&A between Bonnie Raitt and Photography: Robin Laanenen, Daniel the Madison Renaissance Hotel in Seat- Ann Wilson. Th e conference will also Sheehan, Valerie Trucchia tle. Th ree thousand people from around showcase almost 250 female-led perfor- Layout: Karen Caropepe Distribution Coordinator: Jack Gold the world attended the fi rst ROCKRGRL mances in various venues throughout Mailing: Lola Pedrini Music Conference including the legend- downtown Seattle at night, and a variety Program Manager: Karen Caropepe ary Ronnie Spector and Courtney Love. of workshops and sessions. Registra- Icons Ann and Nancy Wilson of Heart tion and information at: www.rockrgrl. Calendar Information: mail to 3429 were honored with the fi rst Woman of com/conference, or email info@rockrgrl. Fremont Place #309, Seattle WA Valor lifetime achievement Award. com. 98103; fax to (206) 547-6286; or email [email protected] Board of Directors: Fred Gilbert EARSHOT JAZZ presents.. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

TIRESIAN SYMMETRY (Cuneiform Rune 346) Format: CD

Bio information: JASON ROBINSON Title: TIRESIAN SYMMETRY (Cuneiform Rune 346) Format: CD Cuneiform publicity/promotion dept.: 301-589-8894 / fax 301-589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: JAZZ / AVANT-JAZZ Saxophonist/Composer Jason Robinson Takes a Mythic Journey with New Album: Tiresian Symmetry featuring Robinson with All-Star Band: George Schuller, Ches Smith, Marty Ehrlich, Liberty Ellman, Drew Gress, Marcus Rojas, Bill Lowe, JD Parran A ubiquitous and often pivotal figure in the stories and myths of ancient Greece, the blind prophet Tiresias was blessed and cursed by the gods, experiencing life as both a man and a woman while living for hundreds of years. In saxophonist/composer Jason Robinson’s polydirectional masterpiece Tiresian Symmetry, he doesn’t seek to tell the soothsayer’s story. Rather for his seventh album as a leader, he’s gathered an extraordinary cast of improvisers to investigate the nature of narrative itself in a jazz context. The music’s richly suggestive harmonic and metrical relationships elicit a wide array of responses, but ultimately listeners find their own sense of order and meaning amidst the sumptuous sounds. For Robinson, a capaciously inventive artist who has flourished in a boggling array of settings, from solo excursions with electronics and free jazz quartets to roots reggae ensembles and multimedia collectives, Tiresian Symmetry represents his most expansive project yet. “I was attracted to the myth of the soothsayer, who tells the future even when it’s not welcome information,” Robinson says. “But on a more technical level I was intrigued by the numerical relationships. -

Earshot Jazz October 2001 (Festival Issue)

Welcome to the 13th ANNUAL Earshot Jazz Festival This year we come to our celebration of jazz, the remarkable A aron Parks, a sure sign tha t the fu land. typically regarded as a uniquely American manifes ture o f jazz is in good hands, at Tula’s. Seattle’s excit The production of the Earshot Jazz festival is tation of the creative spirit, with a tenacious grief ing Living Daylights headlines at the Rainbow that the collective effort o f many hard working staff, vol over the atrocities o f September 11th and a dark, un n igh t. unteers, and audience members. We are grateful to settled sense o f ou r future. T h e fu ll im pa ct o f these The big news in our festival this year concerns the many community members who provide input still-evolving events seems limitless — so large that two landmark concerts in two o f Seattle’s finest halls. and w o rk on the Earshot Jazz festival, and the in they appear to be ushering in an entire new “age.” We are honored to present Keith Jarrett with Gary creasing numbers of audience members who look A n age tha t no one seems qu ite ready to name. Peacock and Jack DeJohnette at Benaroya H all, and forward to each year’s offerings. Like jazz itself, our grief and uncertainty seem, the legendary Dave Brubeck Quartet at the Para This year we bring more artists to the region for at first glance, to be about America. -

Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Finding Aid Prepared by Audrey Abrams, Simmons GSLIS Intern

Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Finding aid prepared by Audrey Abrams, Simmons GSLIS intern This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit July 31, 2014 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Berklee College Archives 2014/02/11 1140 Boylston St Boston, MA, 02215 617-747-8001 Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Historical note................................................................................................................................................4 Scope and contents........................................................................................................................................ 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................4 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................4 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................5 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 8 - Page 2 - Berklee Oral History Project BCA-011 Summary Information Repository Berklee College Archives Creator Berklee College