Research Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halarose Borough Council

RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Election of Parish Councillors For the Area of West Malling Parish I, the undersigned, being the returning officer, do hereby certify that at the election of Parish Councillors for the above mentioned Parish, the following persons stood validly nominated at the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely 4pm on Wednesday, 3rd April 2019 and have been duly elected Parish Councillors for the said Parish without contest. NAME OF PERSONS ELECTED HOME ADDRESS Barkham, Gwyneth Villanelle 132 St Leonards Street, West Malling, ME19 6RB Bullard, Keith Malcolm 112 St Leonards St, West Malling, Kent, ME19 6PD Byatt, Richard John 8 Police Station Road, West Malling, ME19 6LL Dean, Trudy 49 Offham Road, West Malling, Kent, ME19 6RB Javens, Linda Madeline 11 Woodland Close, West Malling, Kent, ME19 6RR Medhurst, Camilla 41 Offham Road, West Malling, Kent, ME19 6RB Cade House, 79 Swan St, West Malling, Kent, ME19 Smyth, Yvonne Mary 6LW Stacpoole, Miranda Jane 107 Norman Road, West Malling, ME19 6RN Flat F Meadow Bank Court, Meadow Bank, West Malling, Stapleton, Nicholas George ME19 6TS Stevens, Peter Graham 68 Sandown Road, West Malling, Kent, ME19 6NR Thompson, David Richard William 4 Police Station Road, West Malling, Kent, ME19 6LL Dated: Thursday, 04 April 2019 Julie Beilby Returning Officer Tonbridge and Malling Borough Council Gibson Building Gibson Drive Kings Hill West Malling ME19 4LZ Published and printed by Julie Beilby, Returning Officer, Tonbridge -

TH ROW4 HQ 460 Birling Luddesdown Ryarsh Trottiscliffe

KENT COUNTY COUNCIL REGISTER OF DEPOSITS KCC Reference number: TH/ROW4/HQ/460 ✓ Highways Statement ✓ Landowner Statement Date Deposit application received: 26/02/2018 Date on which any Highways Declaration expires: 26/02/2038 …………………………………………………………………………….. Details of the land: Districts Tonbridge & Malling; Gravesham Parishes Birling, Ryarsh, Trottiscliffe; Luddesdown Address & postcode of Land to the west of Ryarsh and east buildings on land parcels of Trottiscliffe forming part of the Birling Estate, Coldrum Lane, West Malling, Kent, ME19 Nearest town/city Birling OS 6-figure grid reference TQ 661 608 KCC Contact: Definitive Map Officer Tel: 03000 41 71 71 Email: [email protected] Form CA17 Notice of landowner deposit statement under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 and/or section 15A(1) of the Commons Act 2006 The Kent County Council An application to deposit a map and statement under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 and deposit a statement under section 15A(1) of the Commons Act 2006 has been made in relation to the land described below and shown edged red on the accompanying map, reference 08/18. Deposit applications enable a landowner to protect their land against the establishment of any/further public rights of way and/or registration of the land as a village green. PLEASE NOTE: This deposit does not affect existing recorded public rights of way but may affect any unrecorded rights over the land described below. Deposits made under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980 may prevent deemed dedication of public rights of way over such land under section 31(1) of that Act. -

A Guide to Parish Registers the Kent History and Library Centre

A Guide to Parish Registers The Kent History and Library Centre Introduction This handlist includes details of original parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts held at the Kent History and Library Centre and Canterbury Cathedral Archives. There is also a guide to the location of the original registers held at Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre and four other repositories holding registers for parishes that were formerly in Kent. This Guide lists parish names in alphabetical order and indicates where parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts are held. Parish Registers The guide gives details of the christening, marriage and burial registers received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish catalogues in the search room and community history area. The majority of these registers are available to view on microfilm. Many of the parish registers for the Canterbury diocese are now available on www.findmypast.co.uk access to which is free in all Kent libraries. Bishops’ Transcripts This Guide gives details of the Bishops’ Transcripts received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish handlist in the search room and Community History area. The Bishops Transcripts for both Rochester and Canterbury diocese are held at the Kent History and Library Centre. Transcripts There is a separate guide to the transcripts available at the Kent History and Library Centre. These are mainly modern copies of register entries that have been donated to the -

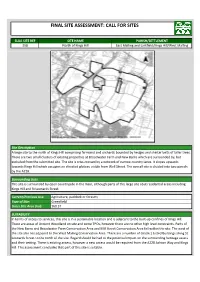

Final Site Assessment: Call for Sites

FINAL SITE ASSESSMENT: CALL FOR SITES SLAA SITE REF SITE NAME PARISH/SETTLEMENT 358 North of Kings Hill East Malling and Larkfield/Kings Hill/West Malling Site Description A large site to the north of Kings Hill comprising farmland and orchards bounded by hedges and shelter belts of taller trees. There are two small clusters of existing properties at Broadwater Farm and New Barns which are surrounded by, but excluded from the submitted site. The site is criss-crossed by a network of narrow country lanes. It slopes upwards towards Kings Hill which occupies an elevated plateau visible from Well Street. The overall site is divided into two parcels by the A228. Surrounding Uses This site is surrounded by open countryside in the main, although parts of this large site abut residential areas including Kings Hill and St Leonards Street. Current/Previous Use: Agriculture, paddock or forestry Type of Site: Greenfield Gross Site Area (ha): 160.37 SUITABILITY In terms of access to services, this site is in a sustainable location and is adjacent to the built-up confines of Kings Hill. There are areas of Ancient Woodland on site and some TPOs, however there are no other high level constraints. Parts of the New Barns and Broadwater Farm Conservation Area and Mill Street Conservation Area fall within the site. The west of the site also lies adjacent to the West Malling Conservation Area. There are a number of Grade 1 Listed Buildings along St. Leonards Street to the north of the site. Regard should be had to the potenital impact on the surrounding heritage assets and their setting. -

JBA Consulting

B.2 DA02 - Tonbridge and Malling Rural Mid 2012s6726 - Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP (v1.0 October 2013) v Tonbridge and Malling Stage 1 SWMP: Summary and Actions Drainage Area 02: Tonbridge and Malling Rural Mid Area overview Area (km2) 83.2 Drainage assets/systems Type Known Issues/problems Responsibility Southern Water and Thames Water Sewer (foul and surface water Sewer networks There are issues linked with Southern Water systems. (latter very small portion in NW (Ightham, Addington)) corner of drainage area) Known fluvial issues associated with the River Bourne at Watercourses Main River Environment Agency Borough Green. Known fluvial issues associated with ordinary watercourses in Ightham, Nepicar Oast, Ryarsh, Borough Kent County Council and Tonbridge Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River Green, Birling, Birling Ashes Hermitage and St Leonard's and Malling Borough Council Street. Lower Medway Internal Drainage Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Board Watercourses, drains and ditches Non-Main River No specific known problems Riparian Flood risk Receptor Source Pathway Historic Evidence Records of regular flooding affecting the road and National Trust land Heavy rainfall resulting in A: Mote Road Mote Road surface water run off FMfSW (deep) indicates a flow route following the ordinary watercourse, not explicitly affecting the road. Flooding along Redwell Lane is a regular problem and recently in 2012 sandbags were needed to deflect water. Records of flooding Redwell Lane, Old Lane and Tunbridge Road along Old Lane appear to be Heavy rainfall resulting in isolated to 2008, although the road FMfSW (deep) also indicates Old Lane as a pathway B: Ightham Common surface water run off and was recorded as repeatedly flooded overloaded sewers over several weeks. -

Malling Rd Kent

MALLING RD KENT (Parishes: Addington, Allington, Aylesford, Birling, Borough Green, Burham, Ditton, East Malling, East Peckham; Ightham, Leybourne, Mereworth, Offham, Platt, Plaxtol, Ryarsh, Shipbourne, Snodland, Stansted, Trottiscliffe, Wateringbury, West Malling, West Peckham, Wouldham and Wrotham) Sources/Coverage: LDS IGI LDS KFHS Other Batch No Addington C(1562-1874) C109981-2 M(1568-1836) M109981-2 Nil Allington C(1630-1874) C109991-2 C(1630-1876) M(1630-1877) M109991-2 M(1640-1877) 1M B(1633-1876) Aylesford C(1635-1861) C036511-3 M(1654-1837) M036511-3 M(1750-1812) 2M Birling C(1558-1874) C130931-2 M(1711-1877) M130932 Nil Burham C(1627-1879) C130951+ M(1626-1876) M130951 Nil Ditton C(1567-99) C131013 C(1633-1885) C131011-2+ M(1665-1837) M131011--4 M(1665-1749) 4C East C(1813-52) C165411 C(1558-1812) Peckham M(1558-1812) B(1558-1812) CD 27 East Malling C(1518-1897) C131581-3+ C(1570-1899) M(1570-1875) M(1570-1901) B(1570-1924) CD 23 Ightam C(1559-1889) C131501-3+ M(1560-1876) M131501-3+ 2C 2M Leybourne C(1560-1875) C131561-2 CMB(1560- 1812) M(1560-1875) M131561-2 Fiche 110 1M LDS IGI LDS KFHS Other Batch No Mereworth C(1560-1897) C135011-3+ CMB(1559- 1812) M(1560-1852) M135011-3 Fiche 117 8C 5M Offham C(1558-1874) C135061-2 M(1538-1852) M135061-2 M(1813-50) Nil Plaxtol C(1805-68) C167161 M(1649-1754) M044409-10 M(1813-35) M167161 Nil Ryarsh C(1560-1876) C017821-4 C(1560-1812) M(1559-1876) M017821-2 M(1560-1811) 2M B(1560-1812) CD 19 Shipbourne C(1560-1682) P015171 C(1719-46) C015172 C(1793-1812) I025034 M(1560-1831) M015171—3+ -

MARDON HOUSE, PINESFIELD LANE, TROTTISCLIFFE, KENT, ME19 5EN 01732 884422 [email protected]

MARDON HOUSE, PINESFIELD LANE, TROTTISCLIFFE, KENT, ME19 5EN 01732 884422 [email protected] www.hillier-reynolds.co.uk £825,000 FREEHOLD This is a stunning 6 bedroom detached family home that offers an abundance of space. Found in an idyllic position with stunning countryside views. Wonderful garden for all to enjoy with beautiful Summer House/Studio. If you are searching for a spacious home in a rural, countryside setting then this amazingly spacious 6 bedroom detached home may well be the end of your search. Before you enter this lovely home we would advise you to turn around! The views you have are from the edge of the beautiful Trosley Country Park & the famous Pilgrims Way on one side and all the way down the road overlooking Trottiscliffe and Addington villages and beyond. These views give you the best idea of the peaceful, countryside setting that this home enjoys. They get even better when you proceed upstairs. Once you're inside you immediately get an idea of the amount of space and rooms this home benefits from. Found off of the first entrance hallway is the study, ideal if you wish to work from home or need somewhere quiet for the children to do homework. There is a large storage cupboard that is big enough to hold the number of coats and shoes needed for a home of this size and its occupants. Next is the downstairs W.C, a must for a large, busy family home. All this and you have not entered the main part of the house! The inner hallway allows access to the main living areas of the home. -

Kent Downs AONB Landscape Design Handbook That Kent’S Aonbs Are Protected and Enhanced’

1.0 Introduction 1 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Context duty on relevant authorities, public bodies and statutory undertakers to The Kent Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) is a take account of the need to conserve and enhance the natural beauty of nationally important protected landscape, whose special characteristics AONB landscapes when carrying out their statutory functions. include its dramatic landform and views, rich habitats, extensive ancient woodland, mixed farmland, rich historic and built heritage, and its 1.4 Consultation tranquillity and remoteness. Within its bounds it shows a considerable In preparing this document an initial consultation was undertaken in variation in landscape character that encompasses open and wooded November 2003 with representatives of local authorities, parish councils, downs, broad river valleys, dry valleys, arable farmland vales, wooded local farmers etc. to discuss the scope, content and look of the document. greensand ridge, and open chalk cliff coastline. “The Kent Downs AONB The views of the consultees have been sought with the intention that the is a capital resource that underpins much economic activity in Kent. Its handbook be adopted as a Supplementary Planning Document (SPD) high quality environment helps to attract businesses, contributes to the and be available from the AONB Unit. Further information can be found quality of life that people in the county value so highly and supports a in the Statement of Consultation available from the AONB Unit. substantial visitor economy”. (South East England Development Agency) 1.5 Users 1.2 Purpose of the Handbook The handbook is intended to be used by the following audiences: The purpose of the handbook is to provide practical, readily accessible Residents and community groups design guidance to contribute to the conservation and enhancement of Local businesses, farmers and landowners the special characteristics of the AONB as a whole, and the distinctiveness Developers, architects, planners and designers of its individual character areas. -

Area Planning Committee Part 1 Public Alleged Unauthorised

Area Planning Committee Alleged Unauthorised Development Trottiscliffe 10/00184/UNAUTU 564399 159771 Downs Location: Trosley Farm Addington Lane Trottiscliffe West Malling Kent 1. Purpose of Report: 1.1 To report the unauthorised erection of decking on land used for the keeping or grazing of horses. 2. The Site: 2.1 The site is a large agricultural field to the south side of Addington Lane. 3. History: 3.1 No relevant planning history. 4. Alleged Unauthorised Development: 4.1 Without planning permission the construction of decking. 5. Determining Issues: 5.1 The Authority received information that a caravan had been placed on the site. On investigation it was clear that the caravan at that time and at the current time was not occupied but used by the landowner as when he is on site to look after his horses. The caravan is used as a shelter and for the making of refreshments and as such can be described as a chattel not requiring the benefit of planning permission from this Authority, as it involves neither a change of use nor operational development. 5.2 However, it was clear when the site was inspected that a decking area had been created adjacent to but not attached to the caravan. The erection of this decking is operational development that requires planning permission from the local planning authority. It was made clear to the owner that this development would require the benefit of planning permission and he was invited to make a planning application. Despite a number of reminders no such application has been submitted. -

Outcome of Public Consultation on the Proposed Closure of Trottiscliffe

Item No B3 By: Director - Operations To: School Organisation Advisory Board – 7 September 2006 Subject TROTTISCLIFFE CHURCH OF ENGLAND (VOLUNTARY CONTROLLED) PRIMARY SCHOOL, WEST MALLING: PROPOSED CLOSURE - OUTCOME OF PUBLIC CONSULTATION. Classification: Unrestricted File Ref: _______________________________________________________________________________ Summary: This report sets out the results of the public consultation. It seeks the views of the School Organisation Advisory Board on the issuing of a public notice for the proposed closure of Trottiscliffe Church of England (Voluntary Controlled) Primary School by September 2007 at the earliest. ______________________________________________________________________________ Introduction 1. (1) The School Organisation Advisory Board at its meeting on 18 May 2006 supported the undertaking of a public consultation on the proposal to close Trottiscliffe Church of England (Voluntary Controlled) Primary School. (2) Trottiscliffe CE (VC) Primary School has 61 children on roll (January 2006 PLASC) against a net capacity of 84, giving it a 27.38% surplus capacity. (3) The school is situated within the village of Trottiscliffe. Approximately 37% of its pupils are drawn from within a 1 mile radius, while approximately 40% live more than 3 miles from the school. The latter live mainly in Snodland and East Malling. A map is attached in Appendix 1, which shows the location of the school and the pupil distribution. Background 2. (1) In the Tonbridge and Malling areas there are 40 primary schools with a combined net capacity of 10,441. There are currently 8,891 pupils attending these schools giving a surplus capacity of 14.8%. Surplus places are slightly higher in the Malling area than in Tonbridge. (2) Due to increasing pupil numbers, surplus places in the Malling area are forecast to reduce to 7.25% by 2010, whereas in Tonbridge, the surplus is projected to rise to 14.87%. -

Villagers Face Bigger Blasts from Quarry

downsmail.co.uk MallingMalling EditionEdition Maidstone & Malling’s No. 1 newspaper FREE May 2017 No. 241 News Tory candidate debates with pupils Trail of fame FORMER Tonbridge & Malling BLUE plaques will put up in MP Tom Tugendhat came face to Wateringbury to remember face with all his political oppo- the village’s past VIPs. 3 nents at a local school. The Malling School has been staging its own election campaign Phone box’s new call in which pupils represent the na- AN unwanted phone kiosk at tional parties. Mr Tugendhat Ryarsh has been given a spoke to debating society students new lease of life. 3 and then at a Q&A session. Head Carl Roberts said he was proud his students asked “mature and Pantomime time informed” questions. Pictured are STARS hit the town to unveil plans Mr Tugendhat with Henry Cox, for panto fun at the Josh Burt, Matt Pettet, Emma Hazlitt Theatre. 4 Stone and Kestra Willett. Drugs danger PARENTS warned after drugs are found on a footpath at Villagers face bigger a church. 6 Top Twenty DOWNS Mail throws a party to blasts from quarry celebrate 20 years in newspaper publishing. 10 PLANS to use bigger explosives at a quarry near Offham are creating shock- Ofsted praise waves among locals. TWO schools are celebrating after The explosions at Gallagher’s gressively worse, with more resi- Offham Parish Council began they were awarded Blaise Farm Quarry have been a reg- dents reporting disturbance, includ- compiling a dossier of the disruption “good” grades by Ofsted. 12 ular feature of life for villagers, who ing windows rattling and ornaments to homes last month and has urged are alerted by the company to blast- juddering. -

Environmentally Sensitive Site Map SSSI Kent Ashford

Thanet Coast U P Medway Estuary and Marshes G Thanet Coast THN Medway Estuary & Marshes Tankerton Slopes and Swalecliffe Medway Estuary & Marshes Cobham Woods Peter`s Pit Medway Estuary & Marshes TLL Cobham Woods Elmley The Swale Halling to Trottiscliffe The Swale The Swale HTG Escarpment The Swale The Swale H D Asset Information - Analysis & Reporting S R J F [email protected] C Margate North Downs Woodlands YD Birchington-on-Sea LEGEND Swale Westgate-on-Sea Meopham Rochester 2 Longfield J Herne Bay Thanet Coast & Sandwich Bay Tree Preservation Orders E Broadstairs Chatham S Sandwich & Pegwell Bay Sole Street VIR Rainham (Kent) Whitstable Conservation Areas Kemsley Thanet Coast and Sandwich Bay Ramsgate Halling Newington Stodmarsh Contaminated Land S WM Sittingbourne Stodmarsh Stodmarsh Teynham Stodmarsh Minster DU Stations Stodmarsh Queendown Warren Faversham Rail Lines Holborough to Burham Marshes Ramsar* Holborough to Burham Marshes Aylesford Stodmarsh Special Protected Areas* Selling Sturry Pit Sandwich Bay Allington Quarry Barming Bearsted Chartham Bekesbourne Special Areas of Conservation* Maidstone West Blean Woods F Allington Quarry Hollingbourne DM R Blean Complex National Nature Reserves* East Farleigh ive Adisham r Le Wateringbury n Harrietsham West Blean & Thornden Woods SSSI within 500m of railway* Lenham Sandwich Bay to Hacklinge Marshes Sandwich Bay to Hacklinge Marshes SSSI with Site Manager Statement* Yalding Down Bank r Lydden and Temple Ewell Downs Hothfield Common u 1 Shepherds Well DU