Ready to Learn Programming S295A200002

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

08-02-2021 Agenda Packet.Pdf

AGENDA DELANO CITY COUNCIL REGULAR MEETING August 2, 2021 DELANO CITY HALL, 1015 – 11th Avenue 5:30 P.M. IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE GOVERNOR NEWSOM’S EXECUTIVE ORDER #N-08-21, THIS MEETING WILL BE CONDUCTED FULLY VIA TELECONFERENCE, DUE TO THE CURRENT RESTRICTIONS BY SAID ORDER AND CENTERS FOR DISEASES CONTROL AND PREVENTION (CDC) GUIDELINES. THE PUBLIC WILL HAVE ACCESS TO CALL IN, LISTEN TO THE MEETING AND PROVIDE PUBLIC COMMENT. IN ACCORDANCE WITH GOVERNOR NEWSOM’S EXECUTIVE ORDER N-08-21, THERE WILL NOT BE A PHYSICAL LOCATION FROM WHICH THE PUBLIC MAY ATTEND. IN ORDER TO CALL INTO TH E MEETING PLEASE SEE THE DIRECTIONS BELOW. CALL TO ORDER INVOCATION FLAG SALUTE ROLL CALL PRESENTATIONS AND AWARDS Featured Pet – Tabitha PUBLIC COMMENT: The public may address the Council on items which do not appear on the agenda. The Council cannot respond nor take action on items that do not appear on the agenda but may refer the item to staff for further study or for placement on a future agenda. Comments are limited to 3 minutes for each person and 15 minutes on each subject. Please state your name and address for the record. CONSENT AGENDA: The Consent Agenda consists of items that in staff’s opinion are routine and non-controversial. These items are approved in one motion unless a Councilmember or member of the public removes a particular item. 1) Authorization to waive the reading of any ordinance in its entirety and consenting to the reading of such ordinances by title only 2) Warrant Register in the amount of $3,044,398.54 3) Minutes of regular City Council Meeting of July 19, 2021 4) Acceptance and Approval of the City of Delano Quarterly Investment Report 5) Resolution adopting the 2020-2021 Kern Multi-Jurisdiction Hazard Mitigation Plan (MJHMP) 6) Approval of agreement with Youth Educational Sports, Inc. -

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

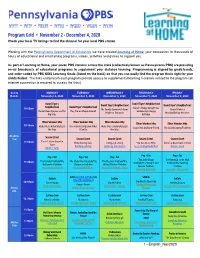

December 4, 2020 Check Your Local TV Listings to Find the Channel for Your Local PBS Station

Program Grid • November 2 - December 4, 2020 Check your local TV listings to find the channel for your local PBS station. Working with the Pennsylvania Department of Education, we have created Learning at Home, your connection to thousands of hours of educational and entertaining programs, videos, activities and games to support you. As part of Learning at Home, your seven PBS stations across the state (collectively known as Pennsylvania PBS) are providing on-air broadcasts of educational programs to supplement your distance learning. Programming is aligned by grade bands, and color-coded by PBS KIDS Learning Goals (listed on the back) so that you can easily find the program that's right for your child/student. The links underneath each program provide access to supplemental learning materials related to the program (an internet connection is required to access the links). Grade MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY Bands November 2, 2020 November 3, 2020 November 4, 2020 November 5, 2020 November 6, 2020 Daniel Tiger’s Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Neighborhood Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood Daniel’s Happy Song/Prince 10:00am The Family Campout/A Game Daniel Makes a Daniel Does Gymnastics/The Play Pretend/Super Daniel! Wednesday’s Happy Night for Everyone Mistake/Baking Mistakes Big Slide Birthday Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why Elinor Wonders Why 10:30am Make Music Naturally/Light The Tomato Drop/Look What Make Music Naturally/Light -

Familienmodelle in Video-On-Demand-Serien: Analyse 3 Der Beispiele

Familienmodelle in Video-on-Demand-Serien: Analyse 3 der Beispiele Das Gesamtbild einer TV-Familie konstituiert sich aus diversen Faktoren. Anhand dieser Faktoren möchte ich den folgenden analytischen Teil strukturieren. Der weitreichenden Analyse meines Korpus geht dabei die exemplarische Analyse der Serie Ozark voran (3.1), die strukturell von der Untersuchung des Korpus abweicht. Zu Beginn der Korpusanalyse sollen die familiären Rollenmuster und geschlechtlichen Konstruktionen analysiert werden, also die Positionen, die eine Figur innerhalb eines Familiengefüges bzw. innerhalb einer familienzentrierten Serienhandlung einnehmen kann (3.2). Dabei unterscheide ich zwischen weibli- chen und männlichen Rollen und thematisiere zudem Bedeutung sowie textinterne Wertung von Rollen, die von heteronormativen Strukturen abweichen. Bezüglich meiner Beispiele bedeutet dies konkret, die Darstellung homo- und transsexueller Charaktere zu untersuchen. Diese Charaktere zählen zwar auch in die Rollenbe- reiche der Mütter, Töchter, Söhne und Väter (und werden in diesem Rahmen auch genannt), nehmen in den analysierten Serien jedoch eine offenkundige Sonder- rolle ein. Ohne dabei in irgendeiner Weise eine ausgrenzende oder abwertende Strategie verfolgen zu wollen, ist dementsprechend eine eigenständige Untersu- chung notwendig. Nach dieser Analyse isolierter Rollen werde ich die möglichen Verhältnisse der Charaktere zueinander untersuchen (3.3). Dies schließt sowohl innerfamiliäre Beziehungen ein als auch Beziehungen von Familienmitgliedern zu außerfamiliären Charakteren. Aus den Beziehungen der Charaktere zueinander ergeben sich diverse Modelle von Familie, die durch die Texte ebenfalls unter- schiedlich gewichtet werden (3.4). Über die Rollen, Beziehungsgeflechte und Elektronisches Zusatzmaterial Die elektronische Version dieses Kapitels enthält Zusatzmaterial, das berechtigten Benutzern zur Verfügung steht https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-34766-6_3. © Der/die Autor(en) 2021 89 J. -

MPTA Annual Report

ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT LEGACY-FUNDED CONTENT & INITIATIVES JULY 1, 2017 - JUNE 30, 2018 KSMQ-TV LAKELAND PBS PIONEER PUBLIC TV PRAIRIE PUBLIC TWIN CITIES PBS WDSE-WRPT Artwork by Jeanne O’Neil The six public media services of the Minnesota Public Television Association (MPTA) harness the power of media and build upon their tradition of creating high-quality programs that sustain viewers in order to document, promote and preserve the arts, culture and history of Minnesota’s communities. Moorhead/Crookston Duluth/Superior/The Iron Range 800-359-6900 218-788-2831 www.prairiepublic.org www.wdse.org Appleton/Worthington/Fergus Falls Bemidji/Brainerd 800-726-3178 800-292-0922 www.pioneer.org www.lptv.org Minneapolis/Saint Paul Austin/Rochester 651-222-1717 800-658-2539 www.tpt.org www.ksmq.org Table of CONTENTS MPTA President Welcome LEGACY Quotes & Numbers What can we do together? MPTA Stations & Legacy Funding… …Advance early childhood learning ________________________ 1 …Help people access arts, culture & history ________________________ 3 …Strengthen cultural bonds ________________________ 5 …Grow the creative economy up north ________________________ 7 …Preserve language for new generations ________________________ 9 …Boost visibility for emerging multicultural artists __________________ 11 Awards & Nominations ____________________________________________________ 13 A look at our year Station Reports KSMQ-TV __________________________________________________________ 17 LAKELAND PBS _______________________________________________________ 37 -

Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices

25528 Federal Register / Vol. 61, No. 99 / Tuesday, May 21, 1996 / Notices DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Closing Date, published in the Federal also purchase 74 compressed digital Register on February 22, 1996.3 receivers to receive the digital satellite National Telecommunications and Applications Received: In all, 251 service. Information Administration applications were received from 47 states, the District of Columbia, Guam, AL (Alabama) [Docket Number: 960205021±6132±02] the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, File No. 96006 CTB Alabama ETV RIN 0660±ZA01 American Samoa, and the Commission, 2112 11th Avenue South, Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Ste 400, Birmingham, AL 35205±2884. Public Telecommunications Facilities Islands. The total amount of funds Signed By: Ms. Judy Stone, APT Program (PTFP) requested by the applications is $54.9 Executive Director. Funds Requested: $186,878. Total Project Cost: $373,756. AGENCY: National Telecommunications million. Notice is hereby given that the PTFP Replace fourteen Alabama Public and Information Administration, received applications from the following Television microwave equipment Commerce. organizations. The list includes all shelters throughout the state network, ACTION: Notice, funding availability and applications received. Identification of add a shelter and wiring for an applications received. any application only indicates its emergency generator at WCIQ which receipt. It does not indicate that it has experiences AC power outages, and SUMMARY: The National been accepted for review, has been replace the network's on-line editing Telecommunications and Information determined to be eligible for funding, or system at its only production facility in Administration (NTIA) previously that an application will receive an Montgomery, Alabama. announced the solicitation of grant award. -

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 in the Matter of Bright House Networks, LLC for Determinatio

Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Bright House Networks, LLC ) CSRNo. _ ___ ) For Determination of Effective Competition in: ) Brevard County, FL (FL0014) ) Grant-Valkaria, FL (FL1348) To: Office of the Secretary Attn: Chief, Media Bureau PETITION FOR SPECIAL RELIEF Bright House Networks, LLC, ("Bright House Networks" or the "Company"), pursuant to Sections 76.7 and 76.907 of the Commission's rules, 1 requests that the Commission find that it faces "effective competition" in the above-referenced Florida franchise areas (the "Franchise Areas"). The Communications Act of 1934, as amended (the "Act"), and the Commission's rules provide that cable television rates may be regulated only in the absence of effective competition.2 Cable operators are entitled to demonstrate that effective competition exists on a franchise-by- franchise basis. 3 When a cable operator demonstrates that effective competition is present within a franchise area, cable rates in the affected area are no longer subject to regulation. 4 1 47 C.F.R. §§ 76.7 and 76.907. 2 47 U.S.C. § 543(a)(2); 47 C.F.R. § 76.905(a). 3 47 C.F.R. § 76.907. 4 See Implementation ofSections ofthe Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992, Rate Regulation, 8 FCC Red. 5631, 5664-5665 (1993) ("Rate Order"). DWT 21 18866lvl 0102538-000001 Under the "competing provider" test set forth in Section 623(1)(l)(B) ofthe Act and Section 76.905(b)(2) of the Commission's rules (the "Competing Provider Test"), a cable system will be deemed subject to effective competition if the franchise area is: (i) served by at least two unaffiliated multichannel video programming distributors, each of which offers comparable programming to at least 50 percent of the households in the franchise area; and (ii) the number of households subscribing to multichannel video programming other than the largest multichannel video programming distributor exceeds 15 5 percent of the households in the franchise area. -

December 2017 Best Bets

DECEMBER 2017 BEST BETS GREAT PERFORMANCES GREAT BRITISH BAKING SHOW THE MOODY BLUES: CHRISTMAS MASTERCLASS 2017 DAYS OF FUTURE PASSED LIVE Join judges Mary Berry and Paul Hollywood as they detail Experience the memorable 50th anniversary performance how to make perfect mince pies, Christmas pudding, and of the band's seminal album, including “Knights in White Christmas cake, and introduce some tasty treats for the Satin,” recorded live with a full orchestra from Toronto's holiday season. Sony Centre. Jeremy Irons narrates. TPT 2 Monday, December 11, 8 p.m. TPT 2 Saturday, December 2, 7 p.m. TPT LIFE Sunday, December 3, 10 p.m. CALL THE MIDWIFE: HOLIDAY SPECIAL 2017 Join the midwives as they battle snow, ice, power cuts, and frozen pipes to provide patient care during the A ST. THOMAS CHRISTMAS: coldest winter in 300 years. Valerie helps a young couple that experiences a traumatic birth, and Sister Julienne SO BRIGHT THE STAR tries to reunite a family. This TPT production was recorded before a live audience TPT 2 Monday, December 25, 8 p.m. at Orchestra Hall in downtown Minneapolis. A St. Thomas TPT LIFE Wednesday, December 27, 8 p.m. Christmas: So Bright the Star celebrates the Advent and Christmas season by drawing from a songbook of familiar traditional carols and innovative contemporary selections. TPT 2 Friday, December 22, 8 p.m. TPT LIFE Sunday, December 24, 8 p.m. ON THE COVER 2 /tptpbs @tpt A New Year Celebration Piano Concerto No. 1 Dec 31 8:30pm (includes post-concert party and countdown to New Year) Jan 1 2pm (includes complimentary coffee and donuts) Osmo Vänskä, conductor / Inon Barnatan, piano Minnesota Dance Theatre Symphony No. -

Tv Highlights for Central

MediaCorp Pte Ltd Daily Programme Listing okto SUNDAY 1 DECEMBER 2013 7.00AM oktOriginal: Team Word (Eps 3 - 4 / Local Info-ed / Schoolkids / R) (益智节目) Scrumble, Fumble and Tumble your way in the newest word game show that not only tests your spelling abilities, but your speed, agility and teamwork skills as well! Each week, two teams pit against each other using big letter tiles in three different challenges. 8.00 oktOriginal: The Seekers (Eps 5 - 6 / Local Drama / Schoolkids / R) (电视剧) Life for three kids is forever changed when one of them inherits a weathered treasure map that dates back to the Second World War. Could it point to the location of the legendary lost treasures of Yamashita’s Gold? They must combine their wits and perseverance in this race against time and evildoers. 9.00 Marsupilami - Hoobah Hoobah Hop! (Ep 7 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) Hector is spending a year studying nature in the Palombian jungle where he soon becomes best buddies with the legendary Marsupilami and his family! 9.30 The Adventures Of Tintin (Ep 7 / Schoolkids / Cartoon / R) (卡通片) The original TinTin animated series featuring the classic adventures of the globetrotting young journalist, TinTin, and his dog, Snowy. 10.00 Generator Rex (Ep 13 / Schoolkids / Cartoon / R) (卡通片) From the creators of Ben 10 comes Generator Rex, a series about a teen with extraordinary powers. 10.30 Cardfight Vanguard (Sr 3 / Ep 8 / Schoolkids / Cartoon / R) (卡通片) Exciting 3rd season of Cardfight Vanguard. 11.00 Digimon Fusion Battles (Ep 20 / Schoolkids / Cartoon) (卡通片) Taiki is abducted by DarkKnightmon while moving between zones, but once he realizes Taiki has no dark power in his heart, he deems him useless and releases him. -

KLCS Curriculum-Related Programming 3/16/20–3/20/20

KLCS Curriculum-Related Programming 3/16/20–3/20/20 GRADES Pre-K–3 4–8 9–12 TIME MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY 6:00 AM Wild Kratts* Wild Kratts* Wild Kratts* Wild Kratts* Wild Kratts* Science Science Science Science Science 6:30 AM Peg + Cat* Peg + Cat* Peg + Cat* Peg + Cat* Peg + Cat* Math Math Math Math Math 7:00 AM CyberChase* CyberChase* CyberChase* CyberChase* CyberChase* Math Math Math Math Math 7 :30 AM SciGirls* SciGirls* SciGirls* SciGirls* SciGirls* Science Science Science Science Science 8:00 AM NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: 8:30 AM Inner Worlds Mars Jupiter Saturn Ice Worlds Science Science Science Science Science 9:00 AM History Detectives: History Detectives: History Detectives: History Detectives: History Detectives: 9:30 AM Psychophone Manhattan Project St. Valentine's Day Sideshow Babies Tokyo Rose Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies 1 0:00 AM Ancient Skies: Ancient Skies: Ancient Skies: Africa's Great Africa's Great 1 0:30 AM Gods & Monsters Finding the Center Our Place Civilizations* Civilizations* Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies Social Studies 11:00 AM Breakthrough Ideas: Breakthrough Ideas: Breakthrough Ideas: Breakthrough Ideas Breakthrough Ideas 11:30 AM The Telescope* The Airplane* The Robot* Math & Science Math & Science Math & Science Math & Science Math & Science 1 2:00 PM NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: NOVA: 12:30 PM Inner Worlds Mars Inner Worlds Saturn Ice Worlds Science Science Science Science Science 1 :00 PM Shakespeare Light Falls: American Masters: American Masters: 1:30 PM Uncovered* Einstein* Louisa May Alcott* Margaret Mitchell* ELA American Masters: Science/ Social ELA ELA 2: 00 PM Maya Angelou* Studies Masterpiece: Shakespeare ELA 2:30 PM Little Women 2/3 Uncovered* Masterpiece: Little ELA ELA 3:00 PM American Masters: Women 1/3* N. -

WEEK 7 May 11-15 9:30 - 11:00 A.M

WEEK 7 May 11-15 9:30 - 11:00 A.M. PBS Arkansas Shows SciGirls SciGirls showcases bright, curious, real tween girls putting science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) to work in their everyday lives. Arthur Arthur's goals are to help foster an interest in reading and writing, to encourage positive social skills, and to model age-appropriate problem-solving strategies. Odd Squad The show focuses on two young agents, Olive and Otto, who are part of the Odd Squad, an agency whose mission is to save the day whenever something unusual happens in their town. Kid Stew The purpose of the show is to inspire and enlighten kids of all ages to learn more about books, music, the arts, and science. Cyberchase Cyberchase is an ongoing action-adventure children’s television series focused on teaching basic STEM concepts. Apple Seeds Garden-based learning reaches into a deep part of all of us. When young students plant a seed, watch it grow, harvest a vegetable and taste something that they had a hand in growing, they remember that experience. Literacy Corner Choose at least 2-4 literacy learning opportunities to practice your reading, writing and communication skills. Don’t forget to grab a good book and read one hour daily. ● Online Options: Lexia, Spelling City or ReadWorks ● Read an Article: Read “Gecko Feet & Space Robots” and answer the comprehension questions. ● Robot Interaction Script: In SciGirls: Robots to the Rescue, the girl scientists wrote a script for the robot to play tic-tac-toe. Think about a simple task that a robot could complete with a person. -

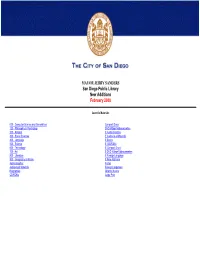

San Diego Public Library New Additions February 2008

MAYOR JERRY SANDERS San Diego Public Library New Additions February 2008 Juvenile Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities Compact Discs 100 - Philosophy & Psychology DVD Videos/Videocassettes 200 - Religion E Audiocassettes 300 - Social Sciences E Audiovisual Materials 400 - Language E Books 500 - Science E CD-ROMs 600 - Technology E Compact Discs 700 - Art E DVD Videos/Videocassettes 800 - Literature E Foreign Language 900 - Geography & History E New Additions Audiocassettes Fiction Audiovisual Materials Foreign Languages Biographies Graphic Novels CD-ROMs Large Print Fiction Call # Author Title J FIC PETSCHEK Petschek, Joyce S. The silver bird : a tale for those who dream J FIC/ADLER Adler, Susan S., 1946- Samantha learns a lesson : a school story J FIC/BARRY Barry, Dave. Peter and the Starcatchers J FIC/BAUM Baum, L. Frank (Lyman Frank) The life and adventures of Santa Claus J FIC/BLADE Blade, Adam. Tartok the ice beast J FIC/BUCKLEY Buckley, Michael. Once upon a crime J FIC/BUTLER Butler, Leah. Owen's choice : the night of the Halloween vandals J FIC/BYNG Byng, Georgia. Molly Moon's incredible book of hypnotism J FIC/CARROLL Carroll, Lewis, 1832-1898. Alice in Wonderland and Through the looking-glass J FIC/COLFER Colfer, Eoin. Artemis Fowl J FIC/CURTIS Curtis, Christopher Paul. Elijah of Buxton J FIC/DAHLBERG Dahlberg, Maurine F., 1951- The story of Jonas J FIC/DANZIGER Danziger, Paula, 1944- You can't eat your chicken pox, Amber Brown J FIC/DENENBERG Denenberg, Barry. Mirror, mirror on the wall : the diary of Bess Brennan J FIC/DITERLIZZI DiTerlizzi, Tony. Lucinda's secret J FIC/DITERLIZZI DiTerlizzi, Tony.