Reading Taken from Today's Isms, William Ebenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorial Day, Holland, MI, May 31, 1954” of the Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box D14, folder “Memorial Day, Holland, MI, May 31, 1954” of the Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. The Council donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box D14 of The Ford Congressional Papers: Press Secretary and Speech File at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library !' Ladies and Gentlemen - Memorial Day is indeed a solemn and significant occasion for all Americans. It is the day set aside for honoring the memory of the heroic men and women who have given their lives to preserve the unity of our country, or to defend it against the a~gressions of others. In this year of Our Lord Nineteen hundred and :fifty... four, its significance is emphasized, for again the interests of the United States and the principles and institutions it represents are the subject of aggression. One of the fundamental characteristics of the American people is their desire to live in peace. -

The Rise of FASCISM

,~ The Rise of FASCISM F. L. Carsten .. tr~. , . .. BATSFORD ACADEMIC AND EDUCATIONAL LTD;:(; 'lo"\" t' I 1I6 NATIONAL SOCIALISM: THE FORMATIVE YEARS MEIN KAMPF II7 the ReichsTPelzr will be on our side, officers and men .... One day the from Goring. 44 Yet Ludendorff refused to heed the warnil).gs:, it was hour will come when these wild troops will grow to battalions, the only some years later that he finally broke with Hitler~,;,,:t . battalions to regiments, the regiments to divisions, when the old IfHitler could influence some very senior officers ,there is no doubt ' cockade will be lifted from the mire, when the old flags will wave in about the fascination which his appeal had for'the young lieutenants > front of us.•.•' 43 He was not burning his bridges. and cadets, and for the soldiers of the world war. Their world had:Qeen"':, , ' What seems somewhat strange in these events is how Hitler, in spite' T the HohenzoUern Empire and the war, and that world had disappear~d,: ,.' of his low social origin, his wild manners and his lack of any construc as they believed, it had been destroyed·by the November*fI',iminaJ.s. tive programme, could influence and sway not just the crowds, but Hitler promised them vengeance, a national rebirth, a GermanY strong middle-aged and experienced men, such as the judge of the Bavarian and free, cleansed of all alien influence. In Italy thisnatiQnalapp~J high court, Theodor von der Pfordten who was killed at the Odeons was powerful enough although Italy was one of the victorious powers: platz, or the generals Ludendorff and von Lossow. -

Religious Terrorism

6 O Religious Terrorism errorism in the name of religion has become the predominant model for Tpolitical violence in the modern world. This is not to suggest that it is the only model because nationalism and ideology remain as potent catalysts for extremist behavior. However, religious extremism has become a central issue for the global community. In the modern era, religious terrorism has increased in its frequency, scale of violence, and global reach. At the same time, a relative decline has occurred in secular terrorism. The old ideologies of class conflict, anticolonial liberation, and secular nationalism have been challenged by a new and vigorous infusion of sec- tarian ideologies. Grassroots extremist support for religious violence has been most widespread among populations living in repressive societies that do not per- mit demands for reform or other expressions of dissent. What is religious terrorism? What are its fundamental attributes? Religious ter- rorism is a type of political violence motivated by an absolute belief that an other- worldly power has sanctioned—and commanded—terrorist violence for the greater glory of the faith. Acts committed in the name of the faith will be forgiven by the otherworldly power and perhaps rewarded in an afterlife. In essence, one’s religious faith legitimizes violence as long as such violence is an expression of the will of one’s deity. Table 6.1 presents a model that compares the fundamental characteristics of religious and secular terrorism. The discussion in this chapter will review the -

World Domination Games and Its Impact on the 21St Century

DOI: 10.31703/gmcr.2017(II-I).03 | Vol. II, No. I (2017) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/gmcr.2017(II-I).03 | Pages: 44 – 56 p- ISSN: 2708-2105 L-ISSN: 2708-2105 World Domination Games and its Impact on the 21st Century Haseeb Ur Rehman Warrich* | Muhammad Rehman† | Sahrish Jamil‡ Abstract: No other element impacted the historical conditions of the preceding 100 years to such an extent as the war to secure and control the world's reserves of petroleum. Sustainable economic growth after 1873, that discouraged British Empire, arose mechanical economies in Europe. Central Asia remained the object of rivalries and machination by the giant countries of the Europe. World Domination Games started from Pillage Games that lead towards many “Games” such as Great Game, New Great Game, Game Changer and New Game Changer. All prefect countries desire to have a control over the world for the last two centuries. Their efforts turn into numerous clashes and clashes led towards wars. In the twentieth century wars transformed not only their names but also their genetics that has profound impact on the 21st Century. This laid foundation of the emerging new superpowers in every century. Key Words: Great Game, New Great Game, Game Changer, Prefect Game, Pillage Game, Ideologies, World War I & World War II Introduction In the pages of history, world domination means an ideology, a nation or a country enlarging its authority to the position that all other nations are duteous to it. This may be achieved by established political system, a direct or indirect form of government that geopolitically rules the states by means of its implied power. -

The Influence of German National Socialism and Italian Fascism on the Nasjonal Samling, 1933–1936

fascism 8 (2019) 36-60 brill.com/fasc Norwegian Fascism in a Transnational Perspective: The Influence of German National Socialism and Italian Fascism on the Nasjonal Samling, 1933–1936 Martin Kristoffer Hamre Humboldt University of Berlin and King’s College London [email protected] Abstract Following the transnational turn within fascist studies, this paper examines the role German National Socialism and Italian Fascism played in the transformation of the Norwegian fascist party Nasjonal Samling in the years 1933–1936. It takes the rivalry of the two role models as the initial point and focusses on the reception of Italy and Germany in the party press of the Nasjonal Samling. The main topics of research are therefore the role of corporatism, the involvement in the organization caur and the increasing importance of anti-Semitism. One main argument is that both indirect and direct German influence on the Nasjonal Samling in autumn 1935 led to a radi- calization of the party and the endorsement of anti-Semitic attitudes. However, the Nasjonal Samling under leader Vidkun Quisling never prioritized Italo-German rivalry as such. Instead, it perceived itself as an independent national movement in the com- mon battle of a European-wide phenomenon against its arch-enemies: liberalism and communism. Keywords Norway – Germany – Italy – Fascism – National Socialism – transnational fascism – Nasjonal Samling – Vidkun Quisling © Martin Kristoffer Hamre, 2019 | doi:10.1163/22116257-00801003 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc license at the time of publication. Downloaded from Brill.com09/28/2021 09:35:40AM via free access <UN> Norwegian Fascism in a Transnational Perspective 37 In October 19331 – five months after the foundation of the party Nasjonal Sam- ling [NS; National Unity]2 – Norwegian merchant Johan Wilhelm Klüver sent a letter from Tientsin in China addressed to the NS headquarters in Oslo. -

THE ROLE of the UNIT the POST-COLD WAR ROLE of the UNITED STATES of AMERICA in COLD WAR WORLD: a GLOBAL LEADER HEGEMON? Katarina

Journal of Liberty and International Affairs | Vol. 2, No. 2, 2016 | e ISSN 1857-9760 Published online by the Institute for Research and European Studies at www.e -jlia.com © 2016 Katarina Jonev, Hatidza Berisa and Jovanka Sharanovic This is an open access article distributed under the CC -BY 3.0 License. Date of acceptance: August 22, 2016 Date of publication: October 5, 2016 Review article UDC 327.54-021.68:327(73) THE ROLE OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN THE POST-COLD WAR WORLD: A GLOBAL LEADER OR HEGEMON? Katarina Jonev, MA University of Belgrade , Republic of Serbia jonev.katarina[at]gmail.com Hatidža Beriša, PhD Military academy, Republic of Serbia hatidza.berisa[at]mod.gov.rs Jovanka Šaranovi ć, PhD Military academy, Republic of Serbia jovanka.saranovic[at]mod.gov.rs Abstract The authors of this paper deal with the role of the USA in the post -Cold War world and their position from the standpoint of relevant indicators and theoretical considerations. This work also refers to path that the United States took from isolationism to the world domination and considers justification of the position of the USA in the period after the Cold War from the point of hegemonic stability theories, while at the end indicates the diversity of understanding of contemporary thinkers regarding the po sition of the United States as the hegemon or rather “just” a global leader. This paper does not prejudge the final definition of the position of the USA in international relations, but aims to launch discussions on the necessity and justification of the existence of such vision on a global scale. -

Can China Replace the Us As a New Hegemon? the Impact of the Energy Security in China’S Hegemonic Potential

CAN CHINA REPLACE THE US AS A NEW HEGEMON? THE IMPACT OF THE ENERGY SECURITY IN CHINA’S HEGEMONIC POTENTIAL. A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY NIGAR SHIRALIZADE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN THE DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS SEPTEMBER 2016 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences _____________________ Prof. Dr. Tülin Gençöz Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. ___________________ Prof.Dr. Özlem Tür Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science. __________________ Prof. Dr. Faruk Yalvaç Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Faruk Yalvaç (METU, IR) __________________________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Mehmet Fatih Tayfur (METU, IR) __________________________ Asst. Prof. Mehmet Gürsan Şenalp (Atılım University, Economics) _________ I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Signature : iii ABSTRACT CAN CHINA REPLACE THE US AS A NEW HEGEMON? THE IMPACT OF THE ENERGY SECURITY IN CHINA’S HEGEMONIC POTENTIAL. Shiralizade, Nigar MSc., Department of International Relations Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Faruk Yalvaç September 2016, 198 pages This thesis investigates the possibility of ‘change’ in the current world structure initiated by the rising power. -

The Roots of the Religious Cold War: Pre-Cold War Factors

Article The Roots of the Religious Cold War: Pre-Cold War Factors Dianne Kirby Independent Scholar; [email protected]; Tel.: +44-2890-710470 Received: 9 March 2018; Accepted: 30 March 2018; Published: 3 April 2018 Abstract: The article is an examination of the roots of the amalgam of complex forces that informed the ‘religious cold war’. It looks at the near and the more distant past. Naturally this includes consideration of the interwar years and those of the Second World War. It also means addressing divisions in Christianity that can be traced back to the end of the third century, to the official split of 1054 between Catholic and Orthodox, the impact of the Crusades and the entrenched hostility that followed the fifty-seven years imposition on Constantinople of a Latin Patriarch. It surveys the rise of significant forces that were to contribute to, as well as consolidate and strengthen, the religious cold war: civil religion, Christian fundamentalism and the Religious Right. The article examines both western and eastern mobilization of national religious resources for political purposes. Keywords: religious cold war; Christendom; communism; East-West divide; civil religion; Christian fundamentalism; American foreign policy; the Vatican; ecumenical movement 1. Introduction ‘Wherever there is theological talk, it is always implicitly or explicitly political talk also’. Karl Barth, 1939. (Busch 1994, p. 292). The major Cold War belligerents all had histories marked by the intricate interplay between religion and politics. The 21st century witnessed the emergence of a scholarly consensus that there was a religious dimension to the Cold War and that it was a multi-faceted, multi-faith global phenomenon (Kirby 2003, 2013, pp. -

'Just Like Hitler': Comparisons to Nazism in American Culture

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Open Access Dissertations 5-2010 'Just Like Hitler': Comparisons To Nazism in American Culture Brian Scott Johnson University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Brian Scott, "'Just Like Hitler': Comparisons To Nazism in American Culture" (2010). Open Access Dissertations. 233. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/open_access_dissertations/233 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ‘JUST LIKE HITLER’ COMPARISONS TO NAZISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by BRIAN JOHNSON Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2010 English Copyright by Brian Johnson 2010 All Rights Reserved ‘JUST LIKE HITLER’ COMPARISONS TO NAZISM IN AMERICAN CULTURE A Dissertation Presented by BRIAN JOHNSON Approved as to style and content by: ______________________________ Joseph T. Skerrett, Chair ______________________________ James Young, Member ______________________________ Barton Byg, Member ______________________________ Joseph F. Bartolomeo, Department Head -

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer

“For a World Without Oppressors:” U.S. Anarchism from the Palmer Raids to the Sixties by Andrew Cornell A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Social and Cultural Analysis Program in American Studies New York University January, 2011 _______________________ Andrew Ross © Andrew Cornell All Rights Reserved, 2011 “I am undertaking something which may turn out to be a resume of the English speaking anarchist movement in America and I am appalled at the little I know about it after my twenty years of association with anarchists both here and abroad.” -W.S. Van Valkenburgh, Letter to Agnes Inglis, 1932 “The difficulty in finding perspective is related to the general American lack of a historical consciousness…Many young white activists still act as though they have nothing to learn from their sisters and brothers who struggled before them.” -George Lakey, Strategy for a Living Revolution, 1971 “From the start, anarchism was an open political philosophy, always transforming itself in theory and practice…Yet when people are introduced to anarchism today, that openness, combined with a cultural propensity to forget the past, can make it seem a recent invention—without an elastic tradition, filled with debates, lessons, and experiments to build on.” -Cindy Milstein, Anarchism and Its Aspirations, 2010 “Librarians have an ‘academic’ sense, and can’t bare to throw anything away! Even things they don’t approve of. They acquire a historic sense. At the time a hand-bill may be very ‘bad’! But the following day it becomes ‘historic.’” -Agnes Inglis, Letter to Highlander Folk School, 1944 “To keep on repeating the same attempts without an intelligent appraisal of all the numerous failures in the past is not to uphold the right to experiment, but to insist upon one’s right to escape the hard facts of social struggle into the world of wishful belief. -

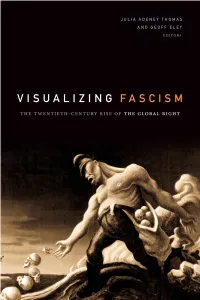

Visualizing FASCISM This Page Intentionally Left Blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors

Visualizing FASCISM This page intentionally left blank Julia Adeney Thomas and Geoff Eley, Editors Visualizing FASCISM The Twentieth- Century Rise of the Global Right Duke University Press | Durham and London | 2020 © 2020 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid- free paper ∞ Designed by Julienne Alexander / Cover designed by Matthew Tauch Typeset in Minion Pro and Haettenschweiler by Copperline Books Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Eley, Geoff, [date] editor. | Thomas, Julia Adeney, [date] editor. Title: Visualizing fascism : the twentieth-century rise of the global right / Geoff Eley and Julia Adeney Thomas, editors. Description: Durham : Duke University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers:lccn 2019023964 (print) lccn 2019023965 (ebook) isbn 9781478003120 (hardback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478003762 (paperback : acid-free paper) isbn 9781478004387 (ebook) Subjects: lcsh: Fascism—History—20th century. | Fascism and culture. | Fascist aesthetics. Classification:lcc jc481 .v57 2020 (print) | lcc jc481 (ebook) | ddc 704.9/49320533—dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023964 lc ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019023965 Cover art: Thomas Hart Benton, The Sowers. © 2019 T. H. and R. P. Benton Testamentary Trusts / UMB Bank Trustee / Licensed by vaga at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. This publication is made possible in part by support from the Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts, College of Arts and Letters, University of Notre Dame. CONTENTS ■ Introduction: A Portable Concept of Fascism 1 Julia Adeney Thomas 1 Subjects of a New Visual Order: Fascist Media in 1930s China 21 Maggie Clinton 2 Fascism Carved in Stone: Monuments to Loyal Spirits in Wartime Manchukuo 44 Paul D. -

Anarchism at the End of the World an Introduction to the Instinct That Won’T Go Away

The Anarchist Library (Mirror) Anti-Copyright Anarchism at the End of the World An Introduction to the Instinct that Won’t Go Away Darren Allen Darren Allen Anarchism at the End of the World An Introduction to the Instinct that Won’t Go Away 10th December 2018 Retrieved on December 10, 2018 from http://expressiveegg.org/ 2018/12/10/anarchism-at-the-end-of-the-world/ usa.anarchistlibraries.net 10th December 2018 Contents What is Anarchism? ..................... 5 Objection 1. Anarchism is inhuman ............ 8 Objection 2: Anarchism is chaos . 10 Objection 3. Anarchism is Violent . 15 Objection 4: Anarchism is parochial . 17 Objection 5: Anarchism is uncivilised . 18 Objection 6: Anarchism is unrealistic . 21 Objection 7: Anarchism is insane . 28 The Choice You Have is between Anarchism and Anar- chism .......................... 32 3 friends, lovers and most effective working groups. We are anar- ‘And now we’ll pull down every single notice, and every chists. single leaf of grass shall be allowed to grow as it likes to.’ Snufkin. The Choice You Have is between Anarchism Anarchism is the only way of life that has ever worked or ever can. and Anarchism It is the only actual alternative to the pseudo-alternatives of the left and right, of optimism and pessimism, and even of theism and athe- What might a free anarchist society look like today? Imagine ism. That being so you would expect it to be widely ignored, ridiculed if we removed the state and all its laws, dismantled our insti- and misunderstood, even by nominal anarchists. tutions and corporations, made attendance at school voluntary, opened the prisons, abolished educational qualifications and all professional accreditation, allowed everyone access to all What is Anarchism? professionally-guarded resources, cancelled all debts, abolished Anarchism is the rejection of domination.