Chassidic Route. Lancut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chassidic Route. Ropczyce

Ropczyce THE CHASSIDIC ROUTE 02 | Ropczyce | introduction | 03 Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was established in March ���� by the Dear Sirs, Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). �is publication is dedicated to the history of the Jewish community of Ropczyce, and is a part Our mission is to protect and commemorate the surviving monuments of Jewish cultural of a series of pamphlets presenting history of Jews in the localities participating in the Chassidic heritage in Poland. �e priority of our Foundation is the protection of the Jewish cemeteries: in Route project, run by the Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland since ����. cooperation with other organizations and private donors we saved from destruction, fenced and �e Chassidic Route is a tourist route which follows the traces of Jews from southeastern Poland commemorated several of them (e.g. in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Kłodzko, Iwaniska, and, soon, from western Ukraine. �� localities, which have already joined the project and where Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazowieckie). �e actions of our Foundation cover the priceless traces of the centuries-old Jewish presence have survived, are: Baligród, Biłgoraj, also the revitalization of particularly important and valuable landmarks of Jewish heritage, e.g. the Chełm, Cieszanów, Dębica, Dynów, Jarosław, Kraśnik, Lesko, Leżajsk (Lizhensk), Lublin, Przemyśl, synagogues in Zamość, Rymanów and Kraśnik. Ropczyce, Rymanów, Sanok, Tarnobrzeg, Ustrzyki Dolne, Wielkie Oczy, Włodawa and Zamość. We do not limit our heritage preservation activities only to the protection of objects. It is equally �e Chassidic Route runs through picturesque areas of southeastern Poland, like the Roztocze important for us to broaden the public’s knowledge about the history of Jews who for centuries Hills and the Bieszczady Mountains, and joins localities, where one can find imposing synagogues contributed to cultural heritage of Poland. -

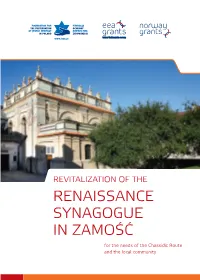

RENAISSANCE SYNAGOGUE in ZAMOŚĆ for the Needs of the Chassidic Route and the Local Community 3

1 REVITALIZATION OF THE RENAISSANCE SYNAGOGUE IN ZAMOŚĆ for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community 3 ABOUT THE FOUNDATION �e Foundation for the Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland was founded in 2002 by the Union of Jewish Communities in Poland and the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO). �e Foundation’s mission is to protect surviving monuments of Jewish heritage in Poland. Our chief task is the protection of Jewish cemeteries – in cooperation with other organizations and private donors we have saved from destruction, fenced and commemorated several burial grounds (in Zakopane, Kozienice, Mszczonów, Iwaniska, Strzegowo, Dubienka, Kolno, Iłża, Wysokie Mazowieckie, Siedleczka-Kańczuga, Żuromin and several other places). Our activities also include the renovation and revitalization of particularly important Jewish monuments, such as the synagogues in Kraśnik, Przysucha and Rymanów as well as the synagogue in Zamość. �is brochure has been published within the framework of the project “Revitalization of the Renaissance synagogue in Zamość for the needs of the Chassidic Route and the local community” implemented by the Foundation for the �e protection of material patrimony is not the Foundation’s only task however. It is equally Preservation of Jewish Heritage in Poland and supported by a grant from Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the important to us to increase the public’s knowledge of the history of the Polish Jews who for EEA Financial Mechanism and the Norwegian Financial Mechanism. centuries contributed to Poland’s heritage. Our most important educational activities include the “To Bring Memory Back” program, addressed to high school students, and POLIN – Polish Jews’ Heritage www.polin.org.pl – a multimedia web portal that will present the history of 1200 Jewish communities throughout Poland. -

ZAŁĄCZNIK NR 16 Do Procedury

ZAŁĄCZNIK NR 16 do Procedury Wykaz tras modelowych w związku z realizacją zamknięć torowych linii kolejowej nr 91/96/609 w następujących lokalizacjach (zmiana nr 6 z ważnością od 14.03.2021 r.): 1) Kraków Bieżanów – Podłęże, Tarnów Mościce - Tarnów - Tarnów Wschód - Wola Rzędzińska - Czarna Tarnowska – Dębica - Ropczyce - Sędziszów Małopolski - Trzciana - Rzeszów Główny - Strażów Długość Numer Stacja Stacja końcowa Stacje pośrednie trasy trasy początkowa [km] 91.01 Bochnia Medyka Tarnów, Przeworsk 207,395 Towarowa 91.02 Dębica Kraków Wola Rzędzińska, Tarnów, Brzesko Okocim, Podłęże 102,762 Prokocim 91.03 Katowice Stalowa Wola Jaworzno Szczakowa, Krzeszowice, Podłęże, Tarnów, Dębica, Rzeszów, Przeworsk Gorliczyna 349,244 Kostuchna Południe 91.04 Klemensów Trzebinia Stalowa Wola Rozwadów Tow., Mielec, Gaj 340,772 91.05 Kraków Nowa Medyka Podłęże, Bochnia, Tarnów Mościce, Tarnów Wschodni, Dębica, Rzeszów Główny, Przeworsk, 237,624 Huta Towarowa Munina, Żurawica, Hurko 91.06 Kraków Dębica Podłęże, Brzesko Okocim, Tarnów, Wola Rzędzińska 102,452 Prokocim 91.07 Kraków Medyka Przeworsk, Rzeszów Główny, Dębica, Tarnów, Bochnia, Żurawica ŻrB 237,189 Prokocim Towarowa 91.08 Kraków Żurawica Bochnia, Tarnów, Dębica, Rzeszów Główny, Przeworsk 227,272 Prokocim 91.09 Medyka Zdzieszowice Żurawica, Przeworsk, Rzeszów Główny, Dębica, Tarnów, Bochnia, Podłęże, Krzeszowice, Jaworzno 401,683 Towarowa Koksownia Szczakowa, Bytom, Gliwice, Sławięcice 91.10 Medyka Bochnia Przeworsk, Tarnów 208,531 Towarowa 91.11 Medyka Dwory Przeworsk, Tarnów, Gaj, Skawina 299,318 -

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts

The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Perspectives on Jewish Texts and Contexts Edited by Vivian Liska Editorial Board Robert Alter, Steven E. Aschheim, Richard I. Cohen, Mark H. Gelber, Moshe Halbertal, Geoffrey Hartman, Moshe Idel, Samuel Moyn, Ada Rapoport-Albert, Alvin Rosenfeld, David Ruderman, Bernd Witte Volume 3 The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Edited by Steven E. Aschheim Vivian Liska In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem In cooperation with the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. ISBN 978-3-11-037293-9 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-036719-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-039332-3 ISSN 2199-6962 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2015 Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: bpk / Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin Typesetting: PTP-Berlin, Protago-TEX-Production GmbH, Berlin Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Preface The essays in this volume derive partially from the Robert Liberles International Summer Research Workshop of the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem, 11–25 July 2013. -

A GENEALOGICAL MIRACLE - Thanks to the Jewish Agency Arlene Blank Rich

cnrechw YCO" " g g-2 "& rgmmE CO +'ID pbP g " 6 p.ch 0"Y 3YW GS € cno I cl+. P. 3 k. $=& L-CDP 90a3-a Y3rbsP gE$$ (o OSN eo- ZQ 3 (Dm rp,7r:J+. 001 PPP wr.r~Rw eY o . 0"CD Co r+ " ,R Co CD w4a nC 1 -4 Q r up, COZ - YWP I ax Z Q- p, P. 3 3 CD m~ COFO 603" 2 %u"d~. CD 5 mcl3Q r. I= E-35 3s-r.~E Y e7ch g$g", eEGgCD CD rSr(o Coo CO CO3m-i-I V"YUN$ '=z CD Eureka was finding that her maiden name was MARK- at the age of 27 to GROSZ JULISKA, age 18. TOLEVOT: THE JOURNAL Of JEWISH GENEALOGY TOLEPOT is the Hebrew word for "genealogyw OVICS MARI. The last column of the register It is difficult to understand why two bro- or llgenerations. " showed that my great-uncle had petitioned to have thers should change their names and why one should 155 East 93 Street, Suite 3C TOLEDOT disclaims responsibility for errors his name changed to VAJDA SAMUEL, which my father choose VAJDA and the other SALGO. My cousin wrote New York, NY 10028 of fact or opinion made by contributors told me about in 1946 when I first became inter- that all she knew about our great-grandparents is but does strive for maximum accuracy. ested in my genealogy. that they were murdered in the town of Beretty6Gj- Arthur Kurzweil Steven W. Siege1 Interested persons are invited to submit arti- In the birth register for the year 1889, I falu. -

Wykaz Projektów Kluczowych Powiatu Ropczycko-Sędziszowskiego Na Lata 2021-2030

Wykaz projektów kluczowych Powiatu Ropczycko-Sędziszowskiego na lata 2021-2030 I. Inwestycje dotyczące całego powiatu Nazwa zadania Lokalizacja Okres realizacji Podkarpacki System Informacji powiat ropczycko - 2014-2021 Przestrzennej sędziszowski Modernizacja szczegółowej powiat ropczycko - 2020-2021 poziomej osnowy geodezyjnej sędziszowski na obszarze powiatu Poprawa jakości bazy ewidencji powiat ropczycko - 2021-2026 gruntów i budynków w trybie sędziszowski modernizacji ewidencji gruntów i budynków Budowa chodników dla Gmina Iwierzyce, Gmina 2021-2026 pieszych na terenie powiatu Ostrów, Gmina Ropczyce, ropczycko – sędziszowskiego Gmina Sędziszów Małopolski, Gmina Wielopole Skrzyńskie Poprawa efektywności powiat ropczycko - 2023-2025 energetycznej budynków sędziszowski użyteczności publicznej Powiatu Ropczycko - Sędziszowskiego z wykorzystaniem OZE II. Inwestycje z podziałem na gminy 1. Gmina Ropczyce Nazwa zadania Lokalizacja Okres realizacji Budowa i przebudowa bazy Ropczyce 2021 technicznej Wydziału Dróg Powiatowych Budowa parku Ropczyce 2021 polisensorycznego oraz boiska wielofunkcyjnego przy Specjalnym Ośrodku Szkolno- Wychowawczym w Ropczycach Budowa ogrodzenia wokół Ropczyce 2021 budynku Powiatowego Centrum Edukacji Kulturalnej w Ropczycach Rozbudowa budynku Liceum Ropczyce 2023-2025 Ogólnokształcącego w Ropczycach Przebudowa drogi powiatowej Gnojnica, ul. Leśna, ul. 2021-2023 Nr 1360R Ropczyce- Gnojnica Ogrodnicza w Ropczycach wraz z leżącymi w jej ciągu ul. Ogrodniczą i Leśną w Ropczycach na odcinku 3,8 km Przebudowa drogi powiatowej Gnojnica 2023-2025 Nr 1343R Gnojnica – Broniszów w m. Gnojnica na dług. 4,0 km Przebudowa drogi powiatowej Ropczyce, Skrzyszów 2025 Nr 1286R Anastazów – Skrzyszów w m. Ropczyce i Skrzyszów na dług. 4,0 km Rozbudowa drogi powiatowej Lubzina, Okonin 2023-2024 Nr 1345R Lubzina – Okonin na dług. 4,0 km Konserwacja i restauracja Lubzina 2021-2026 budynku pałacu Domu Pomocy Społecznej w Lubzinie Zabezpieczenie osuwiska w m. -

Eastern Carpathian Foredeep, Poland) for Geothermal Purposes

energies Review Prospects of Using Hydrocarbon Deposits from the Autochthonous Miocene Formation (Eastern Carpathian Foredeep, Poland) for Geothermal Purposes Anna Chmielowska * , Anna Sowizd˙ zał˙ and Barbara Tomaszewska Department of Fossil Fuels, Faculty of Geology, Geophysics and Environmental Protection, AGH University of Science and Technology, Mickiewicza 30 Avenue, 30-059 Kraków, Poland; [email protected] (A.S.); [email protected] (B.T.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: There are many oil and gas fields around the world where the vast number of wells have been abandoned or suspended, mainly due to the depletion of reserves. Those abandoned oil and gas wells (AOGWs) are often located in areas with a prospective geothermal potential and might be retrofitted to a geothermal system without high-cost drilling. In Poland, there are thousands of wells, either operating, abandoned or negative, that might be used for different geothermal applications. Thus, the aim of this paper is not only to review geothermal and petroleum facts about the Eastern Carpathian Foredeep, but also to find out the areas, geological structures or just AOGWs, which are the most prospective in case of geothermal utilization. Due to the inseparability of geological settings with both oil and gas, as well as geothermal conditionings, firstly, the geological background of the analyzed region was performed, considering mainly the autochthonous Miocene formation. Then, Citation: Chmielowska, A.; geothermal and petroleum detailed characteristics were made. In the case of geothermal parameters, Sowizd˙ zał,˙ A.; Tomaszewska, B. such as formation’s thickness, temperatures, water-bearing horizons, wells’ capacities, mineralization Prospects of Using Hydrocarbon and others were extensively examined. -

Strategia Rozwoju Dębicko-Ropczyckiego Obszaru Funkcjonalnego

STRATEGIA ROZWOJU DĘBICKO-ROPCZYCKIEGO OBSZARU FUNKCJONALNEGO Spis treści Wykaz skrótów............................................................................................................................. 5 Wstęp .......................................................................................................................................... 7 1. Analiza powiązań funkcjonalnych Dębicko-Ropczyckiego Obszaru Funkcjonalnego ............... 11 1.1. Założenia analizy .................................................................................................................... 11 1.2. Dębicko-Ropczycki Obszar Funkcjonalny w analizie wskaźnikami funkcjonalnymi .............. 15 1.3. Dębicko-Ropczycki Obszar Funkcjonalny w analizie wskaźnikami uzupełniającymi ............. 29 1.4. Dębicko-Ropczycki Obszar Funkcjonalny a wyniki innych badań .......................................... 45 1.5. Wnioski końcowe .................................................................................................................. 45 2. Diagnoza Dębicko-Ropczyckiego Obszaru Funkcjonalnego .................................................... 48 2.1. Uwarunkowania wewnętrzne ............................................................................................... 48 2.1.1. Położenie, podstawowe charakterystyki ....................................................................... 48 2.1.2. Rys historyczny, specyfika obszaru ................................................................................ 48 2.1.3. Konkluzje ...................................................................................................................... -

Jewish Genealogy Yearbook 2012 Published by the IAJGS

Jewish Genealogy Yearbook 2012 Published by the IAJGS Hal Bookbinder, Editor Reporting on 147 Organizations Dedicated to Supporting Jewish Genealogy Note that while not highlighted, the links throughout this Yearbook operate. Jewish Genealogy Yearbook 2012 The International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies (IAJGS) is pleased to present the Jewish Genealogy Yearbook on an annual basis in the hopes that it will be of help as you pursue your family research. I want to thank Hal Bookbinder for his long-time devotion to editing the Yearbook and all those who have taken the time to respond to his requests for the information. Hal will also be co-chairing, with Michael Brenner, the 34th IAJGS International Conference on Jewish Genealogy to be held in Salt Lake City, July 27 through August 1, 2014. With very best wishes for successful research. Michael Goldstein President, IAJGS The Jewish Genealogy Yearbook began in 1998 as a section in the syllabus of the Jewish genealogy conference held that year in Los Angeles. The initial edition included reports on about 80 organizations involved in Jewish genealogy. This has grown to 147 organizations involved in Jewish Genealogy. We hope you find it to be a valuable resource. I extend my thanks to the organizational and project leaders who put the effort into gathering, reviewing and submitting the information that appears in this edition of the Yearbook. And, I especially thank Jan Meisels Allen for her ongoing assistance. Hal Bookbinder Editor, Jewish Genealogy Yearbook Jewish Genealogy Yearbook: Copyright © 1998-2012 by the International Association of Jewish Genealogical Societies (IAJGS), PO Box 3624, Cherry Hill, NJ 08034-0556, USA. -

Belarus – Ukraine 2007 – 2013

BOOK OF PROJECTS CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION PROGRAMME POLAND – BELARUS – UKRAINE 2007 – 2013 BOOK OF PROJECTS CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION PROGRAMME POLAND – BELARUS – UKRAINE 2007 – 2013 ISBN 978-83-64233-73-9 BOOK OF PROJECTS CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION PROGRAMME POLAND – BELARUS – UKRAINE 2007 – 2013 WARSAW 2015 CROSS-BORDER COOPERATION PROGRAMME POLAND – BELARUS – UKRAINE 2007-2013 FOREWORD Dear Readers, Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2007-2013 enables the partners from both sides of the border to achieve their common goals and to share their experience and ideas. It brings different actors – inhabitants, institutions, organisations, enterprises and communities of the cross-border area closer to each other, in order to better exploit the opportunities of the joint development. In 2015 all the 117 projects co-financed by the Programme shall complete their activities. This publication will give you an insight into their main objectives, activities and results within the projects. It presents stories about cooperation in different fields, examples of how partner towns, villages or local institutions can grow and develop together. It proves that cross-border cooperation is a tremendous force stimulating the develop- ment of shared space and building ties over the borders. I wish all the partners involved in the projects persistence in reaching all their goals at the final stage of the Programme and I would like to congratulate them on successful endeavours in bringing tangible benefits to their communities. This publication will give you a positive picture of the border regions and I hope that it will inspire those who would like to join cross-border cooperation in the next programming period. -

Publication of the Scientific Papers

Center of European Projects European Neighbourhood Instrument Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2014-2020 Publication of the Scientifi c Papers of the International Scientifi c Conference Cross-border heritage as a basis of Polish-Belarusian-Ukrainian cooperation Edited by: Leszek Buller Ihor Cependa Warsaw 2018 Publisher: Center of European Projects Joint Technical Secretariat of the ENI Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2014-2020 02-672 Warszawa, Domaniewska 39 a Tel: +48 22 378 31 00 e-mail: [email protected] www.pbu2020.eu Publication under the Honorary Patronage of the Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. The International Scientifi c Conference “Cross-border heritage as a basis of Polish-Belarusian-Ukrainian cooperation” was held under the Honorary Patronage of the Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki. The conference was held in partnership with Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University This document has been produced with the fi nancial assistance of the European Union, under Cross-border Cooperation Programme Poland-Belarus-Ukraine 2007-2013. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of the Joint Technical Secretariat and can under no circumstances be regarded as refl ecting the position of the European Union. Circulation: 400 copies ISBN: 978-83-64597-07-7 Scientifi c Committee: Leszek Buller, PhD – Center of European Projects, Cardinal Stefan Wyszynski University in Warsaw Prof. Ihor Cependa, PhD – Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University Prof. Kanstantsin -

Polish Regional Analysis

POLISH REGIONAL ANALYSIS BUILDING REGIONAL RESILIENCE TO INDUSTRIAL STRUCTURAL CHANGE Podkarpackie Region - Poland Polish Partner Managing Authority Rzeszow Regional Development Agency Marshall Office of Podkarpackie Voivodeship Authors: Center for Statistical Research and Education of the Central Statistic Office in co-operation with Rzeszow Regional Development Agency: Marek Duda, Piotr Zawada, Agnieszka Nedza Website Twitter https://www.interregeurope.eu/foundation/ @FOUNDATION_EU Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 3 Summary .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1. General information on Podkarpackie Voivodship ........................................................... 15 1.2 Employment in economic sectors in Podkarpackie Voivodship ........................................ 25 1.3. Industrial change as an element of economic development in the Podkarpackie Voivodship ........................................................................................................................................... 30 1.4. Business climate survey as a picture of changes occurring in Podkarpackie Voivodship in 2016-2020 ......................................................................................................................... 38 1.5. Changes in industry in the Voivodship due to the outbreak of the Covid-19 coronavirus