Daisy by Sean Devine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Programs Around the World in Areas Pertinent to the Study of Media Ecology

The Twenty-First Annual Convention of the Media Ecology Association June 17-20, 2020 Goals of the MEA • To promote, sustain, and recognize excellence in media ecology scholarship, research, criticism, application, and artistic practice. • To provide a network for fellowship, contacts, and professional opportunities. • To serve as a clearinghouse for information related to academic programs around the world in areas pertinent to the study of media ecology. • To promote community and cooperation among academic, private, and public entities mutually concerned with the understanding of media ecology. • To provide opportunities for professional growth and development. • To encourage interdisciplinary research and interaction. • To encourage reciprocal cooperation and research among institutions and organizations. • To provide a forum for student participation in an academic and professional environment. • To advocate for the development and implementation of media ecology education at all levels of curricula. 2020 Executive Board President: Paolo Granata, University of Toronto Vice President: Peggy Cassidy, Adelphi University Vice President-Elect: Adriana Braga, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro Treasurer: Paul A. Soukup, SJ, Santa Clara University Recording Secretary: Cathy Adams, University of Alberta Executive Secretary: Fernando Gutiérrez, Tecnológico de Monterrey Historian: Matt Thomas, Kirkwood Community College Internet Officer: Carolin Aronis, Colorado State University EME Editor-in-Chief: Ernest Hakanen, Drexel University -

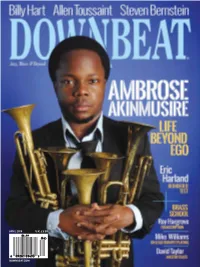

Downbeat.Com March 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 U.K. DOWNBEAT.COM MARCH 2014 D O W N B E AT DIANNE REEVES /// LOU DONALDSON /// GEORGE COLLIGAN /// CRAIG HANDY /// JAZZ CAMP GUIDE MARCH 2014 March 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 3 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes Editorial Intern Kathleen Costanza Design Intern LoriAnne Nelson ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene -

![Tony Schwartz Collection [Finding Aid]. Library Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8976/tony-schwartz-collection-finding-aid-library-of-1278976.webp)

Tony Schwartz Collection [Finding Aid]. Library Of

Tony Schwartz Collection Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Revised March 2014 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/mbrsrs.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/eadmbrs.rs011002 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2012618550 Authors: Carla Arton, Harrison Behl, Callie Holmes, David Jackson, Maya Lerman, Marsha Maguire, Adam Thaxter, Celeste Welch Collection Summary Title: Tony Schwartz collection Inclusive Dates: 1912-2008 Bulk Dates: 1950-2008 Creator: Schwartz, Tony Textual materials: 90.5 linear feet (230 boxes, 1 map case folder, approximately 76,345 items) Language: Collection materials are in English Location: Recorded Sound Reference Center, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The Tony Schwartz Collection consists of multiple formats of material documenting Schwartz's work as a media consultant, audio documentarian, author, radio producer, media theorist, and educator. Location: RPA 00856-01055 (boxes 1-200); RPB 00112-00122 (oversize boxes 213-223); RPC 00084-00087 (oversize boxes 224-227); RPD 00038-00040 (oversize boxes 228-230); RPU 00002 (box 201), RPU 00021-00023 (boxes 202-204), RPU 00024 (box OSU 1), RPU 00025-00032 (boxes 205-212) Map case: RPM 00013 (map folder 1) Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bemporad, Jack. Bleviss, Alan. Bredesen, Phil, 1943- Carey, John, 1946- Carter, Jimmy, 1924- Cherner, Joe. -

![Tony Schwartz Collection [Finding Aid]. Library Of](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7725/tony-schwartz-collection-finding-aid-library-of-2517725.webp)

Tony Schwartz Collection [Finding Aid]. Library Of

Tony Schwartz Collection Authors: Carla Arton, Harrison Behl, Callie Holmes, David Jackson, Maya Lerman, Marsha Maguire, Adam Thaxter, Celeste Welch Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2012 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/mbrsrs.contact Catalog Record: http://lccn.loc.gov/2012618550 Finding aid encoded by Marsha Maguire, 2012 Finding aid prepared using DACS (Describing Archives: A Content Standard) Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mbrsrs/eadmbrs.rs011002 Collection Summary Title: Tony Schwartz collection Inclusive Dates: 1912-2008 Bulk Dates: 1950-2008 Creator: Schwartz, Tony Textual materials: 90.5 linear feet (230 boxes, approximately 76,345 items) Language: Collection materials are in English Location: Recorded Sound Reference Center, Motion Picture, Broadcasting and Recorded Sound Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: The Tony Schwartz Collection consists of multiple formats of material documenting Schwartz's work as a media consultant, audio documentarian, author, radio producer, media theorist, and educator. Location: RPA 00856–01055 (boxes 1–200); RPB 00112–00122 (oversize boxes 213–223); RPC 00084–00087 (oversize boxes 224–227); RPD 00038–00040 (oversize boxes 228–230); RPM 00011, 00013 (map case folders); RPU 00002 (box 201), RPU 00021-00032 (boxes 202-212, OSU 1) Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. People Bemporad, Jack. Bleviss, Alan. Bredesen, Phil, 1943- Carey, John, 1946- Carter, Jimmy, 1924- Cherner, Joe. -

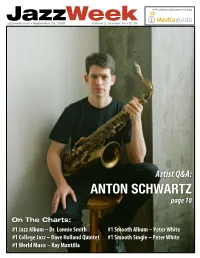

Antonjazz.Com 2014-04

What They’re Saying about Anton Schwartz… “Warm, generous tone, impeccably developed solos and “Tenor saxophonist Anton Schwartz is a guiding light infectious performance energy.” of both the Bay Area & national jazz scenes. – San Francisco Chronicle [He posseses] the commanding tone & boundless creativity of a masterful jazz artist.” “You play the tenor sax like it’s meant to be played!” – SFJAZZ – Illinois Jacquet, Jazz Saxophonist “Warm and intelligent playing... “Soulful and precise, beefy-toned.” and a knack for composing memorable melodies.” – Paul de Barros, Seattle Times – San Jose Mercury News …and his CD Flash Mob (2014) “★★★★… Just about all of these songs have the kind of shapely themes you can imagine other players wanting to cover.” – Jon Garelick, DownBeat “Blazingly hot stuff throughout, Schwartz and company serve up some of the best ensemble playing around and make it sound way too easy. A winner throughout.” – Chris Spector, Midwest Record “A superior tenor saxophonist from Northern California, “Flash Mob… manages to evoke the greatest jazz quintets Anton Schwartz has his own sound and a fresh conception of the past while simultaneously stretching toward the future.” of forward-looking hard bop… Schwartz has created – Ron Netsky, Rochester City Paper a CD worthy of the best of 1960s Blue Note… there are several songs on this set that deserve to become future “If this is hard bop, its 21st century attitude is Schwartz’s standards.” own. His compositions have a distinctive quality that – Scott Yanow, L.A. Jazz Scene incorporates disparate harmonies and rhythms… “Epistrophy” and “La Mesha” are interesting for “The music is imbued with spontaneity, precision, and fun. -

Jazzweek20060925.Pdf

JazzWeek with airplay data powered by jazzweek.com • September 25, 2006 Volume 2, Number 43 • $7.95 Artist Q&A: ANTON SCHWARTZ page 10 On The Charts: #1 Jazz Album – Dr. Lonnie Smith #1 Smooth Album – Peter White #1 College Jazz – Dave Holland Quintet #1 Smooth Single – Peter White #1 World Music – Ray Mantilla JazzWeek This Week EDITOR/PUBLISHER Ed Trefzger MUSIC EDITOR Tad Hendrickson ’ve been writing in this space for the last few weeks about the CONTRIBUTING WRITER/ health of jazz radio. While there are struggles, there are also PHOTOGRAPHER Iopportunities. But this week, I’m going to turn to smooth jazz Tom Mallison radio, which is probably in more dire straits than public jazz ra- PHOTOGRAPHY dio. Barry Solof In the last couple of months, the format has lost stations in Contributing Editors Philadelphia and Peoria, adding to a slide that’s been steady over Keith Zimmerman the last few years. Smooth jazz record sales have been slipping and Kent Zimmerman the majors have been cutting back on their artist rosters. Founding Publisher: Tony Gasparre Why is this happening? Could it be that the format has con- ADVERTISING: Devon Murphy sulted and constricted itself into dullness? Call (866) 453-6401 ext. 3 or A look at the singles chart will show you that the top 20 or so email: [email protected] releases dominate the chart and stay there for weeks on end. That SUBSCRIPTIONS: suggests a stagnation that doesn’t do much to excite or interest a Free to qualified applicants listener. Premium subscription: $149.00 per year, Artists who were key to the format’s creation can’t get them- w/ Industry Access: $249.00 per year To subscribe using Visa/MC/Discover/ selves played today. -

Downbeat.Com April 2014 U.K. £3.50

APRIL 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM APRIL 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 4 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Designer Ara Tirado Design Associate LoriAnne Nelson Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

BALLARD JAZZ FESTIVAL May 17-20, 2017

JAZZ SCENE MAY 2017 / no. 38 / GRATIS 15TH ANNUAL BALLARD JAZZ FESTIVAL May 17-20, 2017 Celebrating 20 years of ORIGIN RECORDS BALLARD AVENUE JAZZ WALK MAINSTAGE CONCERT BROTHERHOOD OF THE DRUM GUITAR SUMMIT CHICO FREEMAN / SCENES BRAD SHEPIK / MARINA ALBERO / JAY THOMAS GRETA MATASSA / ORIGIN ÜBER BAND / GARY HOBBS TRIO / GEORGE COLLIGAN / GAIL PETTIS CLIPPER ANDERSON TRIO / DELVON LAMARR MATT JORGENSEN+451 / PHIL PARISOT QUARTET CHICO TODD BISHOP GROUP / JASNAM DAYA SINGH TARIK ABOUZIED’S HAPPY ORCHESTRA / DAN BALMER / CLAY GIBERSON / 45TH ST. BRASS BILL ANSCHELL QUARTET / BAD LUCK / GREG FREEMAN WILLIAMSON / JOHN STOWELL / COLE SCHUS- TER / RICHARD COLE / BRENT JENSEN / RICK with the George Colligan Trio MANDYCK / TABLE & CHAIRS SHOWCASE COMPLETE FESTIVAL GUIDE INSIDE... SCENES Headliners of the 15TH Annual Ballard Jazz Festival Saturday, May 20th Rick Mandyck: The Return From Now For 14 years, legendary Seattle saxophonist Rick Mandyck was nowhere to be heard. One night at Tula’s, 14 years were erased in one lyrical, magical set. Read the profile on page 12 JOHN STOWELL performing with SCENES SEATTLE JAZZ NEWS jazz and major art exhibits set for 2017. The Art of Jazz Series is sponsored by KPLU Radio and SEATTLE SAXOPHONE INSTITUTE SUMMER hosted by Jim Wilke, who also records most of the concerts CAMP, JULY 31-AUGUST 3 for broadcast on his Jazz Northwest program, Sunday after- noons, at 2pm on 88.5, KNKX. The Summer Saxophone Camp offers four days of im- mersion in saxophone study for beginning through advanced ORIGIN / OA2 RECORDING NEWS high school students. Whether students are interested in jazz, classical, or modern improvisation, the SSI is designed to give saxophonists of all levels of ability the chance to con- Origin Records and OA2 Records announces their spring nect with like-minded students and faculty. -

Anton's Bio Printable Version

Anton Schwartz jazz saxophonist & composer From Louis Armstrong & Lester Young to Charlie Parker & John Coltrane, jazz’s greatest improvisers create music that carries an emotional wallop. It’s a lesson that tenor saxophonist Anton Schwartz learned well. Like the giants from whom he draws inspiration, Schwartz approaches jazz as a vehicle for reaching the heart and the head. At a time when many of his contem- poraries seem to be making music more for their musical colleagues than a wider audience, Schwartz stands out as a player who communicates with his listeners. Tenor sax legend Illinois Jacquet summed up Schwartz’s artist- ry when he told him, “You play the tenor sax like it’s meant to be played.” His latest album, Flash Mob, surged to number six on the jazz radio charts and earned a coveted four-star review in Down Beat magazine, reinforcing his reputation as a passionate but poised improviser and smart purveyor of well- wrought melodies. Schwartz credits an upbringing immersed in jazz and adventurous popular music with shaping his approach to improvising, which melds irresistible rhythmic momentum with emotionally charged lyricism. “I feel lucky because the music I grew up on was Earth Wind & Fire, Jimi Hendrix, The Police, Muddy Waters and Steely Dan… as well as Charlie Parker, Stanley Turrentine, John Coltrane, Lennie Tristano and Wes Montgomery,” says Schwartz. “I’ve never really been interested in making music for other musicians. I want to create music that conveys something complex and intriguing—through the rhythm, the structure, the interplay of melody and harmony—and distill all that into something clear and beautiful.” Schwartz comes to his populist sensibility via a heady path. -

Thomas Kelley Saxophonist, Arranger-Composer, Woodwind Player Curriculum Vita June 2020

1-860-595-8153 TomKelleyMusic.com [email protected] 1/2 SoundCloud: kelleytomj Thomas Kelley Saxophonist, Arranger-Composer, Woodwind Player Curriculum Vita June 2020 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE RECORDING: • Lead alto and flute on Brian Lynch’s GRAMMY-winning big band album The Omni-American Book Club (Hollistic Music Works, 2019) • Lead alto and flute on John Daversa’s triple GRAMMY-winning big band album American Dreamers: Voices of Hope, Music of Freedom (BFM Jazz, 2018) • Alto saxophone on Brian Lynch’s upcoming Songbook Vol. 2 (Hollistic Music Works) • Saxophones on 11 total professional/non-scholastic albums, 2016 to present (five in 2018) SELECTED LIVE EVENTS: • Live auditioned February 2020 for the Herbie Hancock Institute of Jazz Performance. Was the only alto saxophonist to get called back within the live rounds. • 2019 Brubeck Festival: One of 20 Brubeck Fellows (Brubeck Institute Jazz Quintet alumni) invited back for final Brubeck Festival. Performed throughout the week in alumni small-group and big band configurations, also taught lessons and clinics. • Brian Lynch/Spheres of Influence at Pinecrest Gardens (2017) • Alicia Hall-Moran with Shelly Berg, Festival Miami (2017) • World premier of Michael Tilson Thomas’s Playthings of the Wind (2016), performed by the New World Symphony OTHER EMPLOYMENT BESIDES GENERAL FREELANCE: • Woodwind player with Norwegian Cruise Line (2018-2020), Band Master 2020 • Wrote 25 paid full arrangements for seven-piece band format within the last year (with additional transcriptions) • Saxophone students summers of 2016 (with local shop Downright Music), 2013 home • Weekly church pianist, St. Patrick’s Parish in Collinsville, CT (2009-2012) • Won the 2nd tenor audition for the World Famous Glenn Miller Orchestra (2018) EDUCATION DEGREES: • M.M. -

Samantha Boshnack Photo by Daniel Sheehan LETTER from the DIRECTOR EARSHOT JAZZ a Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community

A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community March 2014 Vol. 30, No. 03 EARSHOT JAZZSeattle, Washington Samantha Boshnack Photo by Daniel Sheehan LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR EARSHOT JAZZ A Mirror and Focus for the Jazz Community Executive Director John Gilbreath The face of Seattle jazz … Managing Director Karen Caropepe Earshot Jazz Editor Schraepfer Harvey In reading the nomina- Contributing Writers Bruce Greeley, Steve tions and preparing the Griggs, Peter Monaghan ballot for this year’s Gold- en Ear and Seattle Jazz Calendar Editor Schraepfer Harvey Hall of Fame Awards, it Calendar Volunteer Tim Swetonic has become refreshingly Photography Daniel Sheehan apparent that the face and Layout Karen Caropepe sound of the Seattle jazz Distribution Karen Caropepe, Dan Wight and scene is evolving beauti- volunteers fully. Send Calendar Information to: You may have had a sim- 3429 Fremont Place N, #309 ilar thought as you stud- Seattle, WA 98103 ied your Golden Ear bal- JOHN GILBREATH PHOTO BY BILL UZNAY fax / (206) 547-6286 lot and made your votes. email / [email protected] have predicted. I guess that’s the na- This year’s ballot contains some Board of Directors Bill Broesamle, familiar names, to be sure, but it ture of jazz. Using the annual Golden Ear (president), Femi Lakeru (vice-president), seems that at least half of the nomi- Sally Nichols (secretary), George Heidorn, nees are names you would not have Awards event as a marker, it’s pos- sible to witness a tangible thread ex- Ruby Smith Love, Hideo Makihara, Kenneth seen even five years ago. I find this W. -

When Richard Thompson Returns to the Bay Area in December

***For Immediate Release: Thursday, January 17, 2019*** San Jose Jazz Winter Fest 2019 Thursday, February 14 - Wednesday, February 27, 2019 The Hammer Theatre, Cafe Stritch, The Continental, Art Boutiki, Event Info: sanjosejazz.org/winterfest Tickets: $15 (Advance)/$18 (Door) - $35 (Advance)/$38 (Door), Fest Pass: $260 "Winter Fest has turned into an opportunity to reprise the summer's most exciting acts, while reaching out to new audiences with a jazz-and-beyond sensibility." –KQED Arts Newly Confirmed: The Bad Plus The Havana Cuba All-Stars (Spring 2019 Concert) National Headliners: Gilles Peterson (DJ Set) Catherine Russell With the SJSU Jazz Orchestra Charles McPherson Anton Schwartz and Kenny Washington Aaron Diehl Bells Atlas La Dame Blanche Tiffany Austin with Leon Joyce, Marcus Shelby and Adam Shulman JC Smith Band All-Star Blues Blowout Featuring Fillmore Slim, Kid Anderson and Rick Estrin The Rad Trads Kathy Kosins SJZ Collective plays Mingus (Concert Premiere) Chéjere Richie Goods Next Gen Bay Area Student Ensembles: San Jose Jazz U19s Kuumbwa Jazz Honor Band Folsom High School Jazz Band Berkeley High School Jazz Combo Rio Americano The Inner Circle San Jose, Calif. – Embarking on the 30th Anniversary of their signature Summer Fest, the iconic Bay Area institution San Jose Jazz kicks off 2019 with dynamic arts programming honoring the jazz tradition and ever-expanding definitions of the genre with singular concerts curated for audiences within the heart of Silicon Valley. San Jose Jazz Winter Fest 2019 features some of today’s most distinguished artists alongside leading edge emerging musicians with an ambitious lineup of more than 20 concerts from February 14 - 27, 2019.