Opening Remarks by Mr Desmond Lee, Minister For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

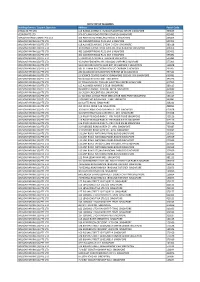

Building Owner / Carpark Operator Address Postal Code

NETS TOP UP MACHINES Building Owner / Carpark Operator Address Postal Code ZHAOLIM PTE LTD 115 EUNOS AVENUE 3 EUNOS INDUSTRIAL ESTATE SINGAPORE 409839 YESIKEN PTE LTD 970 GEYLANG ROAD TRISTAR COMPLEX SINGAPORE 423492 WINSLAND INVESTMENT PTE LTD 163 PENANG RD WINSLAND HOUSE II SINGAPORE 238463 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 461 CLEMENTI ROAD P121-SIM SINGAPORE 599491 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 118 ALJUNIED AVENUE 2 P204_2-GEM SINGAPORE 380118 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 30 ORANGE GROVE ROAD P203-REL RELC BUILDING SINGAPORE 258352 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 461 CLEMENTI ROAD P121-SIM SINGAPORE 599491 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 461 CLEMENTI ROAD P121-SIM SINGAPORE 599491 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 5 TAMPINES CENTRAL 6 TELEPARK SINGAPORE 529482 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 49 JALAN PEMIMPIN APS IND BLDG CARPARK SINGAPORE 577203 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD SGH CAR PARK BOOTH NEAR EXIT OF CARPARK C SINGAPORE 169608 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 587 BT TIMAH RD CORONATION S/C CARPARK SINGAPORE 269707 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 280 WOODLANDS INDUSTRIAL HARVEST @ WOODLANDS 757322 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 15 SCIENCE CENTRE ROAD SCI SINGAPORE SCIENCE CEN SINGAPORE 609081 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 56 CASSIA CRESCENT KM1 SINGAPORE 391056 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 19 TANGLIN ROAD TANGLIN SHOPPING CENTRE SINGAPORE 247909 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 115 ALJUNIED AVENUE 2 GE1B SINGAPORE 380115 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 89 MARINE PARADE CENTRAL MP19 SINGAPORE 440089 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD 32 CASSIA CRESCENT K10 SINGAPORE 390032 WILSON PARKING (S) PTE LTD -

MEDIA RELEASE for Immediate Release Nparks Announces That

MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release NParks announces that over 500 species have been discovered or rediscovered locally over the past five years 48 new targets have been added to the species recovery programme 27 May 2017 – The National Parks Board (NParks) announced that over 500 species have been discovered and rediscovered over the past five years in Singapore by NParks staff, research partners and naturalists. These species include both marine and terrestrial animals, plants including orchids, and insects. These discoveries were made during in-depth surveys, such as the Comprehensive Marine Biodiversity Survey, the Bukit Timah Nature Reserve survey, as well as concerted efforts to survey Singapore’s nature reserves and nature areas in the past five years. The list of discoveries and rediscoveries includes a bee species that is potentially new to science, and a very rare orchid. A small carpenter bee of the genus Ceratina that is potentially new to science was found by chance in 2014 while NParks staff were studying a clump of flowering Tiger Orchids. In 2016, a clump of the Acriopsis ridleyi growing on a tall tree in Bukit Timah Nature Reserve was collected. When it flowered, the Singapore Botanic Gardens herbarium verified that it was a species of orchid thought extinct for over 100 years. More details about the discoveries and rediscoveries can be found in Factsheet A. Despite Singapore being highly urbanised, the fact that we are able to discover and rediscover over 500 species in our city-state in the last five years shows that there is a lot more biodiversity in our City in a Garden that have yet to be discovered and studied. -

List of Chinese Terms Windsor Nature Park

List of Chinese Terms Desmond Lee 李智陞 Senior Minister of State for Home Affairs and National 内政部兼国家发展部高级政务部长 Development Chong Kee Hiong 鍾奇雄 Adviser to Bishan-Toa Payoh GRC GROs 碧山--大巴窑集选区基层组织顾问 Dr Leong Chee Chiew 梁志超博士 Deputy Chief Executive Officer, Professional 国家公园局 Development & Services Cluster 专业发展与服务 Commissioner of Parks and Recreation 副局长 National Parks Board 公园及康乐总监 Wong Tuan Wah 黄墩华 Group Director, Conservation 国家公园局 National Parks Board 自然保护处高级署长 Sharon Chan 曾巧銮 Director, Central Nature Reserve 国家公园局 National Parks Board 中央自然保护区处长 Toh Yuet Hsin 卓悦歆 Deputy Director, Conservation 国家公园局 National Parks Board 自然保护处 副处长 Windsor Nature Park Bukit Timah Nature Reserve 武吉知马自然保护区 Central Catchment Nature Reserve 中央集水区自然保护区 Dairy Farm Nature Park 牛乳场自然公园 Hindhede Nature Park 海希德自然公园 Windsor Nature Park 温莎自然公园 Thomson Nature Park 汤申自然公园 Springleaf Nature Park 春叶自然公园 Chestnut Nature Park 策士纳自然公园 Rifle Range Nature Park 射靶场自然公园 Zhenghua Nature Park 正华自然公园 Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve 双溪布洛湿地保护区 Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve Extension 双溪布洛湿地保护区扩展区 TreeTop Walk 树梢吊桥 Green buffer 缓冲绿带 Hanguana Trail 匍茎草步道 Drongo Trail 大盘尾步道 Squirrel Trail 松鼠步道 Sub-canopy walk 次冠层走道 Marsh habitat 沼泽栖息地 Freshwater stream 淡水溪流 Visitor pavilion 访客亭阁 Boardwalk 木栈道 Singapore Ginger (Zingiber singapurense) 新加坡姜 Singapore Durian (Durio singaporensis) 新加坡榴莲 Drum-stick Ginger (Etlingera maingayi) 马来瓷玫瑰 Memali (Leea angulata) 刺火筒树 Kayu Gaharu (Aquilaria malaccensis) 沉香树 Kayu Arang (Cratoxylum cochinchinense) 黄牛木 Red Dhup (Parishia insignis) 帕里漆木 Greater Racket-tailed -

July 2020 – Dec 2020 J

JulyJ 2020 –Dec 2020 Contents 02 Arts & Culture 31 Overview Calendar 05 Concerts & Performances 41 Volunteer Opportunities 10 Gardening 49 Terms & Conditions 10 Nature 50 Tenants Listing 24 Special Events Parks for Everyone Our parks, gardens and nature areas are for all to enjoy. In this booklet, learn about the wide variety of activities that you can participate in for a fulfilling day at our green spaces from now till December 2020! Do look out for a list of eateries and recreational facilities you can visit in our parks, gardens and nature areas. If you have ideas for new activities, do share them with us at [email protected] Scan the QR code to visit our webpage and get the latest updates on events and programmes. To receive updates on the latest version of the e-Programme Booklet, SMS PB to 77275. Standard message and data rates may apply. ARTS & CULTURE SIGN UP FOR OUR FREE GET UPDATES! E-NEWSLETTERS! SMS the respective programme codes to 77275, or subscribe to our Telegram channel Sign up at www.nparks.gov.sg/ at t.me/NParksBuzz to receive event updates! nparksnewslettersubscription to receive event Standard message and data rates may apply. updates, or learn how you can shape our City in a Garden. Text NPBUZZ to 77275 to receive the e-newsletter on your mobile. Civic District Tree Trail (Programme Code: AC112) 30 Aug 25 Oct 27 Dec Various locations 9am - 10.30am The Civic District Tree Trail takes you through Singapore’s historic Civic District where you will marvel at many majestic and interesting trees, some of which have stood tall for many generations and witnessed the transformation and progress of Singapore through the years FOR MORE INFORMATION: Website: www.nparks.gov.sg/events Monument Trail (Programme Code: AC212) 26 Sep 28 Nov Meeting Point: Cavenagh Bridge, at the entrance of Asian Civilisations Museum 10am - 11.30am Take a stroll along the mouth of the Singapore River, once the heart of Singapore’s commercial activity and entrepôt trade. -

Jan 2020– June 2020 Contents

Jan 2020– June 2020 Contents 02 Arts & Culture 55 Special Events 13 Concerts & Performances 60 Overview Calendar 17 Gardening 75 Volunteer Opportunities 27 Nature 87 Terms & Conditions 52 Sports & Wellness 88 Tenants Listing Parks for Everyone Our parks, gardens and nature areas are for all to enjoy. In this booklet, learn about the wide variety of activities that you can participate in for a fulfilling day at our green spaces from now till June 2020! Do look out for a list of eateries and recreational facilities you can visit in our parks, gardens and nature areas. If you have ideas for new activities, do share them with us at [email protected] Scan the QR code to visit our webpage and get the latest updates on events and programmes. To receive updates on the latest version of the e-Programme Booklet, SMS PB to 77275. Standard message and data rates may apply. ARTS & CULTURE SIGN UP FOR OUR FREE GET UPDATES! E-NEWSLETTERS! SMS the respective programme codes to 77275, or subscribe to our Telegram channel Sign up at www.nparks.gov.sg/e-newsletter @NParksBuzz to receive event updates! to receive event updates, or learn how you Standard message and data rates may apply. can shape our City in a Garden. Text NB01 to 77275 to receive the e-newsletter on your mobile. The Art of Birding : A Nation’s Fascination with Birds (Programme Code: AC111) 23 NOV 2019 – 31 MAR 2020 Singapore Botanic Gardens, Come discover the vibrant world of our feathered friends through CDL Green Gallery @ the eyes of birders and artists in Singapore. -

Singapore Raptor Report October 2020

Singapore Raptor Report October 2020 Greater Spotted Eagle, juvenile, at Telok Blangah Hill Park, 30 Oct 2020, by Tan Gim Cheong. Summary for migrant species: October 2020 was exceptional with 15 migrant raptors species recorded. In contrast, 11 species were recorded in the month of October in the last two years. Thanks much to ardent raptor fans spending time at Henderson Waves and elsewhere. A total of 1768 migrant raptors were recorded, more than twice the number for October 2019, with another 10 unidentified raptors and 393 unidentified accipiters, many of which were probably migrants. The most remarkable record for October 2020 was the Eurasian Hobby Falco subbuteo at Henderson Waves on 23 Oct 2020, reported by Zacc HD, Oliver Tan, Ginny Cheang, Veronica Foo and many others. It was our second record and the only one photographed, a great rarity indeed. Page 1 of 18 Eurasian Hobby, juvenile, at Henderson Waves, 23 Oct 2020, by Zacc HD Eurasian Hobby, juvenile, at Henderson Waves, 23 Oct 2020, by Zacc HD A few other rarities were also recorded. These included two Greater Spotted Eagles Clanga clanga: a distant juvenile photographed at St John’s Island on the 29th, and another closer juvenile at Telok Blangah Hill Park the next day (30th). Two Black Kites Milvus migrans were photographed, a juvenile at Pinnacle@Duxton on the 19th by Angie Cheong, and another juvenile at Taman Jurong on the 30th by Alok Mishra. One sub-adult Rufous-bellied Hawk-Eagle Lophotriorchis kienerii was photographed at Bukit Timah summit on the 23rd by Martin Kennewell and again, two days later, on the 25th, at Dairy Farm Nature Park, by Krishna Gr. -

01. Release Thomson Nature Park.Pdf

MEDIA RELEASE For Immediate Release NParks announces plans for upcoming Thomson Nature Park Latest nature park serves as one of seven green buffers to the Bukit Timah and Central Catchment Nature Reserves Singapore, 8 October 2016 — The National Parks Board (NParks) unveiled plans for Thomson Nature Park today during a site visit by Senior Minister of State for Home Affairs and National Development, Mr Desmond Lee. Located between Old Upper Thomson Road and Upper Thomson Road, the 50 hectare nature park was first announced in 2014 and will complement existing and upcoming nature parks including Springleaf, Chestnut, and Windsor Nature Parks which extend the green buffer for the Central Catchment Nature Reserve (CCNR). It will also enhance the ecological network for biodiversity with its rich flora and fauna. This nature park is also unique because of its rich history as a Hainan village, which was well-known for its Rambutan plantation. Trails will be developed to give visitors a chance to experience the heritage highlights within the site. These include a rare glimpse of ruins, including old houses and foundations of the village that used to be located here and some of the relict trees including majestic Ficus trees estimated to be more than 50 years old. Works in the nature park will commence in early 2017 and be completed by end 2018. Increase in Ecological Linkage and Green Buffer for CCNR The development of Thomson Nature Park is part of a holistic approach to strengthen the conservation of the biodiversity in Singapore’s nature reserves. Like other nature parks, Thomson Nature Park will help to reduce visitorship pressure on the nature reserves by providing alternative venues for the public to enjoy nature-related activities. -

NSS Bird Group Report – October 2019 by Geoff Lim, Alan Owyong (Compiler), Tan Gim Cheong (Ed.)

NSS Bird Group Report – October 2019 by Geoff Lim, Alan Owyong (compiler), Tan Gim Cheong (ed.) The Black-naped Monarch at the Botanic Gardens Black-naped Monarch, Botanic Gardens, 21 Oct 2019, a clear photo by Kelvin Ng Cheng Kwan. Note the unnatural damage to the tail and tertials (broken & frayed tips); the feathers on the mantle also look unnaturally messy 1 The biggest find of the month was the extremely rare Black-naped Monarch, Hypothymis azurea, which also turned out to be the biggest disappointment, as it is in all likelihood an escapee. The monarch was first spotted at the Botanic Gardens on 18 October 2019 by visiting birder, Jan Lile, from Queensland, Australia. Her ebird record was picked up by Andrew Paul Bailey, who alerted birders on FB group ‘Bird Sightings’. Ramesh T. followed the lead the following day and found the bird, thereby alerting others to its continued presence. The bird remained at the Botanic Gardens until 24 October 2019, allowing many birders to see and photograph this great rarity, which unfortunately, turned out to be of captive origin. A review of more than 60 photographs of the monarch showed evidence of unnatural feather damage, particularly to the tertials which were not only frayed, but also broken (tip of top left tertial); there were also unnatural wear to the tips of the primaries and especially to the tail feathers – indeed, the ends of three tail feathers were broken (see pic below); the mantle feathers were unnaturally messy – probably either through being handled or from flying against a cage; overall, the bird had a somewhat untidy appearance, hinting at its captive origin. -

Singapore Bird Report – June 2021 by Geoff Lim, Isabelle Lee & Tan Gim Cheong (Ed.)

Singapore Bird Report – June 2021 by Geoff Lim, Isabelle Lee & Tan Gim Cheong (ed.) Not one but five spectacular species were reported in a hitherto quiet month of June. Read on to find out more! Black Magpie by Kenneth Chow, 9 June 2021 at Hindhede Nature Park. The first surprise find for June was a Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus, on 9 June 2021 at Hindhede Quarry by Vinod Saranathan. Vinod reported that its “weird raucous call” gave it away when he saw it at 6:40pm that day. Another birder, Kenneth Chow, reported seeing the bird at 4:30pm, which he thought was a “strange crow with dirty wings” at the quarry area, and at 5:20pm when he thought it was a Greater Coucal. 1 Fluffy-backed Tit-Babbler by Lawrence Cher, 15 June 2021 at Upper Seletar Reservoir Park. While the community was reeling from the appearance of the Magpie, a hitherto unexpected find in the form of a Fluffy-backed Tit-Babbler, Macronus ptilosus, was made on 15 June 2021 around 2pm at the Upper Seletar Reservoir Park by Lawrence Cher. Lawrence was at the park looking for butterflies to photograph that afternoon as June was relatively quiet in terms of interesting bird life, when he noticed several Pin-striped Tit-Babblers and Chestnut-winged Babbler calling in the background. The birds were popping in and out from view as they foraged, when one popped into the open. Lawrence managed to obtain one clear photo from the series taken; he had thought that it was a Chestnut-winged Babbler until post-processing revealed that it was a different babbler species. -

Annual Report 2019/2020 Content

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 CONTENT 04 --- CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE 06 --- MEMBERS OF THE BOARD 08 --- ORGANISATION STRUCTURE 10 --- A CITY TRANSFORMED BY NATURE 18 --- CONSERVING OUR CITY IN NATURE 26 --- NURTURING OUR CITY IN NATURE 38 --- GROWING OUR CITY IN NATURE 46 --- GARDEN CITY FUND 50 --- SUSTAINABILITY REPORT 56 --- FACTS & FIGURES 62 --- CORPORATE GOVERNANCE 64 --- PUBLICATIONS 70 --- FINANCIAL REVIEW 74 --- FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Seraya (Shorea curtisii) CITY IN NATURE NParks is restoring nature into our urban fabric, building on what we have been doing over the years. With even more nature integrated into our city, this not only strengthens Singapore’s distinctiveness as a highly liveable country, but also helps mitigate the impacts of urbanisation and climate change. With over 350 parks and gardens, four nature reserves, an extensive park connector network as well as verdant streetscapes and nature ways, all residents enjoy easier access to such open spaces while benefitting from lusher greenery that creates cooler surroundings. Scan QR code With the announcement of the One Million to explore what Trees movement in March 2020, NParks is our City in partnering the community to plant a million Nature holds: trees across the island over the next decade. This not only strengthens our natural heritage but leaves a living legacy for future generations to enjoy in our City in Nature. 4 NATIONAL PARKS BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 NATIONAL PARKS BOARD ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 5 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE “While we, as a nation, focus collectively to -

A Natural Connection Nparks Annual Report 2016/2017 1 a Natural Connection

A NATURAL CONNECTION NPARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 1 A NATURAL CONNECTION ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 A NATURAL CONNECTION NPARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016/17 A NATURAL CONNECTION 2 NPARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 NPARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 3 A Natural Connection Human beings have an innate affinity for nature. Even as modernity and urbanisation become the predominant influences in our lives, we still find ourselves turning to nature to enhance our physical and mental well-being. We find respite and rejuvenation in nature and continue to be enchanted and enthralled by the biodiversity in our midst. There is a word for this. It is “biophilia” — the love of living things that leads us on a constant quest for “A Natural Connection”. A NATURAL CONNECTION CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE A NATURAL CONNECTION 4 ANNUAL REPORT 2017 NPARKS ANNUAL REPORT 2016/2017 5 CONTENTS CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE The Learning Forest in the Singapore Botanic Gardens is an example of our commitment to balance conservation with education. Opened in March 2017 at the Gardens’ Tyersall-Gallop Core, visitors can now explore formerly dense forest via boardwalks and elevated walkways, observing the restored wetlands and mature trees of the century-old forest. Beyond the Botanic Gardens, NParks’ stewardship of over 350 parks and gardens allows all Singaporeans to enjoy the restorative benefits of nature close to home. In the west, we are developing Jurong Lake Gardens and our Coastal Adventure Corridor will “ link park connectors so that cyclists, walkers and Even in an urban runners may seamlessly enjoy the variety of habitats environment, it is possible and recreational choices along our eastern coastline. -

Singapore Raptor Report – Nov 2020

Singapore Raptor Report November 2020 Rufous-bellied Hawk-Eagle, adult, on 25 Nov 2020, at Jalan Asas, by Tan Gim Cheong Summary for migrant species: It’s another amazing November, and the arrival of four species boosted the number of migrant raptors to 18 species. The 1st of the month start well with a Northern Boobook photographed at Tuas Bay Lane by Ken Ng, and the first Jerdon’s Baza of the season photographed at Jurong Lake Gardens by Dennis Lim. The one and only Booted Eagle, a dark morph, was photographed by Zacc HD and others at Henderson Waves on the 10th. The first Besra for the season was photographed at Henderson Waves on the 8th, followed by another two the next day – one at Henderson Waves and another at Mandai Track 15. Page 1 of 28 Only two Black Kites were recorded, one photographed by Richard White at Bukit Timah hilltop on the 1st, and another photographed by Ang HouBoon at Pasir Ris Park on the 3rd. There were also only two records of the Common Kestrel, one at Henderson Waves photographed by Ash Foo and others on the 9th, and another at Tuas South photographed by Martti Siponen on the 14th. Unlike the previous two species which were one-day birds, the two Rufous-bellied Hawk-Eagles were detected on many days. The adult was first recorded at Bukit Timah hill top on the 20th, and at Jalan Asas on the 25th, when the juvenile flew in to join it at its perch. However, the adult did not seem to appreciate the company and took off shortly.