The Effect of Bus Fare Increases on Low Income Families

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buses As Rapid Transit

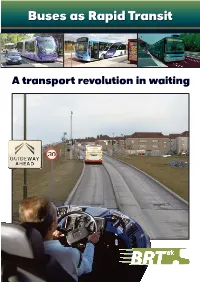

BBuusseess aass RRaappiidd TTrraannssiitt A transport revolution in waiting WWeellccoommee ttoo BBRRTT--UUKK RT is a high profile rapid transit mode that CONTACT BRT-UK combines the speed, image and permanence of The principal officers of BRT-UK are: light rail with the cost and flexibility of bus. BRT-UK Chair: Dr Bob Tebb Bseeks to raise the profile of, and develop a centre b of excellence in, bus rapid transit. b Deputy Chair: George Hazel BRT-UK does not seek to promote bus-based rapid transit b Secretary: Mark Curran above all other modes. BRT-UK seeks to enhance b Treasurer: Alex MacAulay understanding of bus rapid transit and what it can do, and b Membership: Dundas & Wilson allow a fair and informed comparison against other modes. External promotion: George Hazel BRT-UK is dedicated to the sharing of information about b evolving bus-based rubber-tyred rapid transit technology. b Website: Alan Brett For more information please contact us at [email protected]. b Conference organisation: Bob Menzies ABOUT BRT-UK BRT-UK MEMBERSHIP Membership of BRT-UK has been set at £250 for 2007/08. Objectives of the association Membership runs from 1st April-31st March. Membership is payable by cheque, to BRT-UK. Applications for membership The objectives of BRT-UK are: should be sent to BRT-UK, c/o Dundas & Wilson, 5th Floor, b To establish and promote good practice in the delivery Northwest Wing, Bush House, Aldwych, London, WC2B 4EZ. of BRT; For queries regarding membership please e-mail b To seek to establish/collate data on all aspects of BRT -

Memories Come Flooding Back for Ogs School’S Last Link with Headingley

The magazine for LGS, LGHS and GSAL alumni issue 08 autumn 2020 Memories come flooding back for OGs School’s last link with Headingley The ones to watch What we did Check out the careers of Seun, in lockdown Laura and Josh Heart warming stories in difficult times GSAL Leeds United named celebrates school of promotion the decade Alumni supporters share the excitement 1 24 News GSAL launches Women in Leadership 4 Memories come flooding back for OGs 25 A look back at Rose Court marking the end of school’s last link with Headingley Amraj pops the question 8 12 16 Amraj goes back to school What we did in No pool required Leeds United to pop the question Lockdown... for diver Yona celebrates Alicia welcomes babies Yona keeping his Olympic promotion into a changing world dream alive Alumni supporters share the excitement Welcome to Memento What a year! I am not sure that any were humbled to read about alumnus John Ford’s memory and generosity. 2020 vision I might have had could Dr David Mazza, who spent 16 weeks But at the end of 2020, this edition have prepared me for the last few as a lone GP on an Orkney island also comes at a point when we have extraordinary months. Throughout throughout lockdown, and midwife something wonderful to celebrate, the toughest school times that Alicia Walker, who talks about the too - and I don’t just mean Leeds I can recall, this community has changes to maternity care during 27 been a source of encouragement lockdown. -

UCI World Championships 2019

Bus Services in York – UCI World Championships 2019 Buses across the region will disrupted by the UCI World Championships over the week 21–29 September 2019. There may be additional delays caused by heavy traffic and residual congestion in the areas where the race is taking place. Saturday 21 September Route: Beverley, Market Weighton, Riccall, Cawood, Tadcaster, Wetherby, Knaresborough, Ripley, Harrogate Arriva Yorkshire 42 Delays likely between 1100 and 1400 due to road closures around Cawood. 415 Major delays likely between 1100 and 1400 due to road closures around Riccall. Coastliner 840/843 Between 0800 and 1800, buses will not be able to call at stops along York Road or the bus station. Between 1100 and 1430, some buses may not call at Tadcaster at all. Connexions X1 Between 1000 and 1700, buses will divert via Forest Head, Calcutt and Windsor Drive to Aspin. No service to Knaresborough town centre or St James Retail Park at these times. X70 Between 1000 and 1630, buses will run between Harrogate and Plompton Rocks or Follifoot only: http://www.connexionsbuses.com/uncategorized/service-x70-timetable-for-21st-september-only/ 412 All services cancelled East Yorkshire 18 The 1220 from York will wait at North Duffield until the race has passed. This may also cause a delay to the bus that leaves HOSM at 1320. 45/46 The 1020 from York will terminate at Shiptonthorpe and will not call at Market Weighton or HOSM. The 1120 from York will divert from Shiptonthorpe via A614 and will not call at Market Weighton. The 1137 from HOSM will start from Shiptonthorpe, and will not call at HOSM or Market Weighton. -

Annex a Local Transport Plan 2006

Annex A DRAFT Local Transport Plan 2006-2011, Mid-Term Report: Taking on the local transport challenges in York This draft version of the document shows the Mid Term report at its latest stage of production. Some of the text is still to be compiled as not all relevant monitoring data has been collected, and is awaited. It is also acknowledged that further editing of the text is required to make the report more concise. It does, however, provide sufficient information for Executive to either approve the report, or request changes to it, prior to its submission to government, in accordance with the recommendations of the Executive Report. City of York Council, Local Transport Plan 2006-2011, Mid-Term Report Section 1 – Purpose, Background and Context DRAFT PURPOSE, BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT PURPOSE 11.42 Welcome to the Mid-Term Report on City of York’s Local Transport Plan 2006- 2011 (LTP2), which sets out the progress made towards implementing the transport policies, strategies and measures contained within LTP2. It also outlines the programme for delivery for the remainder of the plan period up to 2011, including policies and projects arising from new initiatives since the publication of LTP2, together with a discussion of the risks for achieving this. 11.43 The purpose of this report is to: • Recap the policies and strategies contained in LTP2; • Report on progress of their implementation over the past two years; and • Review LTP2 in light of changes in national and local policy and changes in York since the document was published, and the issues and opportunities available up to and beyond 2011. -

PUBLIC TRANSPORT (The Association Is Grateful to Alan J

1 PUBLIC TRANSPORT (The Association is grateful to Alan J. Sutcliffe for compiling this section for the website.) Services should be checked with the relevant operator. All rail services shown apply until 13 December 2014. Seasonal bus services end in mid October in the case of most Sunday Dalesbus services though some 874 services continue all year. Additional and altered services will be shown when details become available. Leeds to Ilkley by train Mon-Sat. dep. 0602, 0634(SX), 0702, 0729(SX), 0735(SX), 0802, 0832(SO), 0835(SX), 0902 then at 02 and 32 mins past each hour until 1702, 1716(SX), 1732 (SO) 1734(SX), 1747(SX), 1802, 1832, 1902, 1933, 2003, 2106, 2206, 2315 (SO Sat only, SX except Sat). Sun. dep. 0912 then at 12 mins past each hour until 2212, 2316. by bus First Leeds service X84 from Leeds City Bus Station (15 mins walk from Leeds Station) via Otley. Mon-Fri. dep 0640,0705, 0755 then at 35 and 55 mins past each hour until 1655, 1745, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Sat. dep 0615, 0715, 0745, 0805, then at 35 and 55 mins past each hour until 1735, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Sun. dep 0710, 0800, 0910 then at 10 and 40 mins past each hour until 1610, 1710, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Trains from Bradford Forster Square to Ilkley Mon-Fri dep 0615, 0644, 0711, 0745, 0816, then at 16 and 46 mins past each hour until 1616, 1644, 1717, 1746, 1811, 1846, 1941, 2038, 2138, 2238, 2320. Sat dep 0615, 0715, 0816, then at 16 and 46 mins past each hour until 1616, 1644, 1716, 1746, 1816, 1846, 1941, 2038, 2138, 2238, 2320. -

First Bradford, First Halifax, First Huddersfield, First Leeds

First West Yorkshire: (PB0000815) First Bradford, First Halifax, First Huddersfield, First Leeds, Leeds City First York (PB0001747) First West Yorkshire Limited; First York Limited, Hunslet Park Depot, Donisthorpe Street, Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS10 1PL Part of FirstGroup PLC. Depots: Bradford Bowling Back Lane, Bradford, West Yorkshire, BD4 8SP Bramley Bramley Garage, Henconner Lane, Bramley, Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS13 4LD Halifax Skircoat Road, Halifax, West Yorkshire, HX1 2RF Huddersfield Old Fieldhouse Lane, Deighton, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire, HD2 1AG Hunslet Park Hunslet Park Depot, Donisthorpe Street, Leeds, West Yorkshire, LS10 1PL York 7 James Street, York, North Yorkshire, YO10 3WW Outstations: Millwood Millwood Garage, Todmorden, West Yorkshire, OL14 6SB 11101 - 11107 Vehicle Type: Mercedes-Benz Citaro 0.530G Body Type: Mercedes-Benz Citaro Fleet No: Reg No: Seat Type: Year: Depot: Livery: Notes: 11101 BG58OLR AB49T 2009 York York Park & Ride 11102 BG58OLT AB49T 2009 York York Park & Ride 11103 BG58OLU AB49T 2009 York York Park & Ride 11104 BG58OLV AB49T 2009 York York Park & Ride 11105 BG58OLX AB49T 2009 York York Park & Ride 11107 w BG58OMB AB49T 2009 York Park & Ride York 30572 - 31140 Vehicle Type: Volvo B7TL-57 Body Type: Alexander ALX400 Fleet No: Reg No: Seat Type: Year: Depot: Livery: Notes: 30572 WU02KVO H49/29F 2002 Halifax First FSY, 2016 30576 WU02KVT H49/29F 2002 Halifax First FSY, 2016 30943 Y798XNW H49/27F 2001 Huddersfield First Huddersfield 30949 YJ51RRX H49/27F 2001 Huddersfield First Huddersfield 30950 -

Submission from First Leeds Response to Leeds Bus Scrutiny 1

Submission from First Leeds Response to Leeds Bus Scrutiny 1 Background 1.1 Provision of local bus services is governed by the Transport Act 1985, which deregulated services. An operator is able to register with the Traffic Commissioner the intention to provide a bus service detailing the route frequency stopping places and times of operation. Local authorities – in this case West Yorkshire PTE (Metro) – are responsible for providing services that are considered socially necessary but are not provided on a commercial basis by operators. Metro lets contracts for the operation of socially necessary services. 1.2 It follows that a bus operator’s success depends on the attractiveness of the service that they offer. The more the service is used by the public the more successful the operator will be. Reliability punctuality directness and value for money are key elements in the provision of a good service. 1.3 Currently 97.2% of First’s network of services in West Yorkshire is operated on a commercial basis. A process of network reviews throughout West Yorkshire with Metro has resulted in some contracted journeys being operated by First on a commercial basis and is being extended to Leeds. (See 10 Area Bus Network Reviews below) 1.4 Following the changes the proportion of First’s operations in Leeds that are commercial will be c98.25% 2 The Role of WYITA 2.1 In addition to supporting the operation of socially necessary services WYITA through its Executive (Metro) takes responsibility for: • Infrastructure – bus stops and shelters • Bus Stations • Production and distribution of publicity to a standard format 3 Key Issues – Fares 3.1 Operators are responsible for setting the fares charged on bus services. -

First West Yorkshire Fleet

First West Yorkshire Unofficial Fleetlist provided by Sheffield Omnibus Enthusiasts Society Bowling Back Lane, BRADFORD, BD4 8SP; Henconner Lane, BRAMLEY, Leeds, LS13 4LD; Skircoat Road, HALIFAX, HX1 2RF; Old Fieldhouse Lane, HUDDERSFIELD, HD2 1AG; Donisthorpe Street, HUNSLET PARK, Leeds, LS10 1PL Fleet No Registration Chassis Make and Model Body Make and Model Layout Livery Allocation Note 19001 YK06 AOU Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19002 YK06 ATV Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19003 YK06 ATU Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19004 MH06 ZSW Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn ex B 7 FTR 19006 MH06 ZSP Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn ex OO06 FTR 19007 YK06 ATY Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19008 YK06 ATZ Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19009 YK06 AUL Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19011 YK06 AUC Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19012 YJ06 XLR Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB42D First FTR withdrawn 19013 YJ06 XLS Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB42D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19014 YJ56 EAA Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB42D First FTR withdrawn 19015 YJ56 EAC Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19016 YJ56 EAE Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn 19017 YJ56 EAF Volvo B7LA Wright Streetcar AB37D First Hyperlink 72 withdrawn -

PUBLIC TRANSPORT (The Association Is Grateful to Alan J

1 PUBLIC TRANSPORT (The Association is grateful to Alan J. Sutcliffe for compiling this section for the website.) Services should be checked with the relevant operator. All rail services shown apply until 7 December 2013. Seasonal bus services generally start in May, or at Easter in the case of certain Dalesbus services. Additional and altered services will be shown when details become available. Leeds to Ilkley by train Mon-Sat. dep. 0602, 0634(SX), 0702, 0729(SX), 0735(SX), 0802, 0832(SO), 0835(SX), 0902 then at 02 and 32 mins past each hour until 1702, 1715(SX), 1732, 1747(SX), 1802, 1832, 1902, 1932, 2002, 2106, 2206, 2315 (SO Sat only, SX except Sat). Sun. dep. 0912 then at 12 mins past each hour until 2212, 2316. by bus First Leeds service X84 from Leeds City Bus Station (15 mins walk from Leeds Station) via Otley. Mon-Fri. dep 0640,0710, 0755 then at 35 and 55 mins past each hour until 1658, 1748, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Sat. dep 0615, 0715, 0745, 0805, then at 35 and 55 mins past each hour until 1735, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Sun. dep 0710, 0810, 0910 then at 10 and 40 mins past each hour until 1610, 1710, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Trains from Bradford to Ilkley Mon-Fri dep 0615, 0644, 0711, 0745, 0816, then at 16 and 46 mins past each hour until 1616, 1644, 1716, 1746, 1811, 1846, 1941, 2038, 2138, 2238, 2320. Sat dep 0615, 0715, 0816, then at 16 and 46 mins past each hour until 1616, 1644, 1716, 1746, 1816, 1846, 1941, 2038, 2138, 2238, 2320. -

C13324 First NOM.Qxp

THIS DOCUMENT IS IMPORTANT. If you are in any doubt about its contents or the action you should take, you should seek your own financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank manager, solicitor, accountant or other independent financial adviser authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000. If you have sold or otherwise transferred all of your ordinary shares in FirstGroup plc, please send this document and the enclosed form of proxy at once to the purchaser or transferee or to the stockbroker, bank or other agent through whom the transfer or sale was effected for transmission to the purchaser or transferee. Registered office: FirstGroup plc 395 King Street, Aberdeen AB24 5RP Registered in Scotland – No.157176 8 June 2007 To the holders of ordinary shares Dear Sir or Madam Annual General Meeting You will find a notice of the Annual General Meeting of the Company, which is to be held at the Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre, Bridge of Don, Aberdeen AB23 8BL on Thursday 12 July 2007 at 11.00 am, set out on pages 5 to 11 of this letter. The business of the Meeting will include the consideration of resolutions relating to the following matters: • receiving the Annual Report and Financial Statements. • approving the Directors’ Remuneration Report, the full text of which is contained in the Annual Report and Financial Statements. • declaring a final dividend of 10.5 pence per share. • re-electing Moir Lockhead, John Sievwright, Dean Finch and David Leeder as Directors, who retire by rotation under the Company’s Articles of Association and offer themselves for re-election. -

First West Yorkshire Fleet List

© http://westyorkshirebusphotos.wordpress.com/ 11/12/2017 First West Yorkshire Fleet Registration Body Chassis Seat Livery Depot Notes Num. Code 30561 X856 UOK Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/27F First Huddersfield Huddersfield 30562 X857 UOK Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/27F First Huddersfield Huddersfield 30563 X858 UOK Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/27F First Huddersfield Huddersfield 30571 WU02 KVM Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30572 WU02 KVO Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30573 WU02 KVP Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30574 WU02 KVR Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30576 WU02 KVT Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30883 W738 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30885 W772 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Halifax Halifax 30895 W773 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30896 W751 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30897 W752 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Halifax Halifax 30904 W759 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30905 W776 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Halifax Halifax 30906 W761 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Halifax Halifax 30907 W762 DWX Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Halifax Halifax 30908 X763 VUA Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First Bradford Bradford 30909 X764 VUA Alexander Alx400 Volvo B7TL H49/29F First -

Bus Operators in the British Isles

BUS OPERATORS IN THE BRITISH ISLES UPDATED 21/09/21 Please email any comments regarding this page to: [email protected] GREAT BRITAIN Please note that all details shown regarding timetables, maps or other publicity, refer only to PRINTED material and not to any other publications that an operator might be showing on its web site. A & M GROUP Uses Warwickshire CC publications Fleetname: Flexibus Unit 2, Churchlands Farm Industrial Estate, Bascote Road, Harbury CV33 9PL Tel: 01926 612487 Fax: 01926 614952 Email: [email protected] www.flexi-bus.co.uk A2B TRAVEL Uses Merseyside PTE 5 Preton Way, Prenton, Birkenhead CH43 3DU publications Tel: 0151 609 0600 www.a2b-travel.com ABELLIO LONDON No publications 301 Camberwell Road, London SE5 0TF Tel: 020 7805 3535 Fax: 020 7805 3502 Email: [email protected] www.abellio.co.uk ACKLAMS COACHES Leaflets Free Barmaston Close, Beverley HU17 0LA Tel: 01482 887666 Fax: 01482 874949 Email: [email protected],uk www.acklamscoaches.co.uk/local-service AIMÉE’S TRAVEL Leaflets Free Unit 1, Off Sunnyhill's Road, Barnfields Industrial Estate, Leek ST13 5RJ Tel: 01538 385050 Email: [email protected] www.aimeestravel.com/Services AINTREE COACHES Ltd Leaflets Free Unit 13, Sefton Industrial Estate, Sefton Lane, Maghull L31 8BX Tel: 0151 526 7405 Fax: 0151 520 0836 Email: [email protected] www.aintreecoachline.com (PHIL) ANSLOW & SONS COACHES Leaflets Free Unit 1, Varteg Industrial Estate, Varteg Road, Varteg, Pontypool NP4 7PZ Tel: 01495 775599 Email: [email protected]