Think Family, Work Family – Our Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

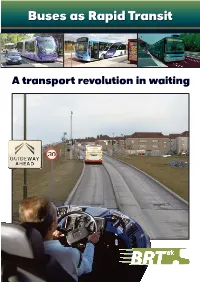

Buses As Rapid Transit

BBuusseess aass RRaappiidd TTrraannssiitt A transport revolution in waiting WWeellccoommee ttoo BBRRTT--UUKK RT is a high profile rapid transit mode that CONTACT BRT-UK combines the speed, image and permanence of The principal officers of BRT-UK are: light rail with the cost and flexibility of bus. BRT-UK Chair: Dr Bob Tebb Bseeks to raise the profile of, and develop a centre b of excellence in, bus rapid transit. b Deputy Chair: George Hazel BRT-UK does not seek to promote bus-based rapid transit b Secretary: Mark Curran above all other modes. BRT-UK seeks to enhance b Treasurer: Alex MacAulay understanding of bus rapid transit and what it can do, and b Membership: Dundas & Wilson allow a fair and informed comparison against other modes. External promotion: George Hazel BRT-UK is dedicated to the sharing of information about b evolving bus-based rubber-tyred rapid transit technology. b Website: Alan Brett For more information please contact us at [email protected]. b Conference organisation: Bob Menzies ABOUT BRT-UK BRT-UK MEMBERSHIP Membership of BRT-UK has been set at £250 for 2007/08. Objectives of the association Membership runs from 1st April-31st March. Membership is payable by cheque, to BRT-UK. Applications for membership The objectives of BRT-UK are: should be sent to BRT-UK, c/o Dundas & Wilson, 5th Floor, b To establish and promote good practice in the delivery Northwest Wing, Bush House, Aldwych, London, WC2B 4EZ. of BRT; For queries regarding membership please e-mail b To seek to establish/collate data on all aspects of BRT -

CROWLEY CLAN NEWSLETTER March 2014 Compiled by Marian Crowley Chamberlain

CROWLEY CLAN NEWSLETTER March 2014 compiled by Marian Crowley Chamberlain Page 1 of 8 Letter from the Taoiseach Michael-Patrick O'Crowley 3 rue de la Harpe Taoiseach Crowley Clan Saint-Leger, France Dear Clansmen and Members, I wish you a wonderful 2014 year, may this New Year bring you health and happiness to your families and dear ones. 2014 is going to be a special year for the Crowleys as we are celebrating the thousandth year of our name. We are coordinating our participation to the anniversary of the battle of Clontarf in Dublin with the O'Briens, the preliminary plans are as follows: • April 23, travel from West Cork to Killaloe, visit of Brian Boru's birth place and round fort homestead. Visit of ClareGalway Castle, lecture on Irish medieval architecture, complementary banquet in the castle Hotel: ClareGalway Hotel - €75 per double room (10 rooms prebooked) • April 24, Travel to Dublin, March of the Clans, Crowley Clan night out • April 25, Reenactment of the Battle of Clontarf (organised by Clontarf Council). Banquet with the O'Briens at Clontarf Castle Hotel - €85 per person. Hotel: Crown Plaza Dublin Airport - €105 per double room (10 rooms prebooked). The Clan Council has decided on the dates for the next clan gathering, it will take place in Kinsale from the 9th to 11th September 2016. Kinsale was again selected as it is both a very attractive city, well situated and with the necessary accommodation for our group. Please note these dates in your calendar to prepare for your travelling. Finally, we are still working on the reediting of the Crowley Clan book - we have had some technical issues due to compatibility of tools the manuscript being on a very old version of StarOffice and on diskettes. -

Musical! Theatre!

Premier Sponsors: Sound Designer Video Producer Costume Coordinator Lance Perl Chrissy Guest Megan Rutherford Production Stage Manager Assistant Stage Manager Stage Management Apprentice Mackenzie Trowbridge* Kat Taylor Lyndsey Connolly Production Manager Dramaturg Assistant Director Adam Zonder Hollyann Bucci Jacob Ettkin Musical Director Daniel M. Lincoln Directors Gerry McIntyre+ & Michael Barakiva+ We wish to express our gratitude to the Performers’ Unions: ACTORS’ EQUITY ASSOCIATION AMERICAN GUILD OF MUSICAL ARTISTS AMERICAN GUILD OF VARIETY ARTISTS SAG-AFTRA through Theatre Authority, Inc. for their cooperation in permitting the Artists to appear on this program. * Member of the Actor's Equity Association, the Union of Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. + ALEXA CEPEDA is delighted to be back at The KRIS COLEMAN* is thrilled to return to the Hangar. Hangar! Select credits: Mamma Mia (CFRT), A Broadway Credit: Jersey Boys (Barry Belson) Chorus Line (RTP), In The Heights (The Hangar Regional Credit: Passing Strange (Narrator), Jersey Theatre), The Fantasticks (Skinner Boys - Las Vegas (Barry Belson), Chicago (Hangar Barn), Cabaret (The Long Center), Anna in the Theatre, Billy Flynn), Dreamgirls (Jimmy Early), Sister Tropics (Richard M Clark Theatre). She is the Act (TJ), Once on This Island (Agwe), A Midsummer founder & host of Broadway Treats, an annual Nights Dream (Oberon) and Big River (Jim). benefit concert organized to raise funds for Television and film credits include: The Big House Animal Lighthouse Rescue (coming up! 9/20/20), and is (ABC), Dumbbomb Affair, and The Clone. "As we find ourselves currently working on her two-person musical Room 123. working through a global pandemic and race for equality, work Proud Ithaca College BFA alum! "Gracias a mamacita y papi." like this shows the value and appreciation for all. -

Memories Come Flooding Back for Ogs School’S Last Link with Headingley

The magazine for LGS, LGHS and GSAL alumni issue 08 autumn 2020 Memories come flooding back for OGs School’s last link with Headingley The ones to watch What we did Check out the careers of Seun, in lockdown Laura and Josh Heart warming stories in difficult times GSAL Leeds United named celebrates school of promotion the decade Alumni supporters share the excitement 1 24 News GSAL launches Women in Leadership 4 Memories come flooding back for OGs 25 A look back at Rose Court marking the end of school’s last link with Headingley Amraj pops the question 8 12 16 Amraj goes back to school What we did in No pool required Leeds United to pop the question Lockdown... for diver Yona celebrates Alicia welcomes babies Yona keeping his Olympic promotion into a changing world dream alive Alumni supporters share the excitement Welcome to Memento What a year! I am not sure that any were humbled to read about alumnus John Ford’s memory and generosity. 2020 vision I might have had could Dr David Mazza, who spent 16 weeks But at the end of 2020, this edition have prepared me for the last few as a lone GP on an Orkney island also comes at a point when we have extraordinary months. Throughout throughout lockdown, and midwife something wonderful to celebrate, the toughest school times that Alicia Walker, who talks about the too - and I don’t just mean Leeds I can recall, this community has changes to maternity care during 27 been a source of encouragement lockdown. -

UCI World Championships 2019

Bus Services in York – UCI World Championships 2019 Buses across the region will disrupted by the UCI World Championships over the week 21–29 September 2019. There may be additional delays caused by heavy traffic and residual congestion in the areas where the race is taking place. Saturday 21 September Route: Beverley, Market Weighton, Riccall, Cawood, Tadcaster, Wetherby, Knaresborough, Ripley, Harrogate Arriva Yorkshire 42 Delays likely between 1100 and 1400 due to road closures around Cawood. 415 Major delays likely between 1100 and 1400 due to road closures around Riccall. Coastliner 840/843 Between 0800 and 1800, buses will not be able to call at stops along York Road or the bus station. Between 1100 and 1430, some buses may not call at Tadcaster at all. Connexions X1 Between 1000 and 1700, buses will divert via Forest Head, Calcutt and Windsor Drive to Aspin. No service to Knaresborough town centre or St James Retail Park at these times. X70 Between 1000 and 1630, buses will run between Harrogate and Plompton Rocks or Follifoot only: http://www.connexionsbuses.com/uncategorized/service-x70-timetable-for-21st-september-only/ 412 All services cancelled East Yorkshire 18 The 1220 from York will wait at North Duffield until the race has passed. This may also cause a delay to the bus that leaves HOSM at 1320. 45/46 The 1020 from York will terminate at Shiptonthorpe and will not call at Market Weighton or HOSM. The 1120 from York will divert from Shiptonthorpe via A614 and will not call at Market Weighton. The 1137 from HOSM will start from Shiptonthorpe, and will not call at HOSM or Market Weighton. -

Annex a Local Transport Plan 2006

Annex A DRAFT Local Transport Plan 2006-2011, Mid-Term Report: Taking on the local transport challenges in York This draft version of the document shows the Mid Term report at its latest stage of production. Some of the text is still to be compiled as not all relevant monitoring data has been collected, and is awaited. It is also acknowledged that further editing of the text is required to make the report more concise. It does, however, provide sufficient information for Executive to either approve the report, or request changes to it, prior to its submission to government, in accordance with the recommendations of the Executive Report. City of York Council, Local Transport Plan 2006-2011, Mid-Term Report Section 1 – Purpose, Background and Context DRAFT PURPOSE, BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT PURPOSE 11.42 Welcome to the Mid-Term Report on City of York’s Local Transport Plan 2006- 2011 (LTP2), which sets out the progress made towards implementing the transport policies, strategies and measures contained within LTP2. It also outlines the programme for delivery for the remainder of the plan period up to 2011, including policies and projects arising from new initiatives since the publication of LTP2, together with a discussion of the risks for achieving this. 11.43 The purpose of this report is to: • Recap the policies and strategies contained in LTP2; • Report on progress of their implementation over the past two years; and • Review LTP2 in light of changes in national and local policy and changes in York since the document was published, and the issues and opportunities available up to and beyond 2011. -

Pathways to Politics

Equality and Human Rights Commission Research report 65 Pathways to politics Catherine Durose, Francesca Gains, Liz Richardson, Ryan Combs, Karl Broome and Christina Eason De Montfort University and University of Manchester Pathways to politics Catherine Durose, Francesca Gains, Liz Richardson, Ryan Combs, Karl Broome and Christina Eason De Montfort University and University of Manchester © Equality and Human Rights Commission 2011 First published Spring 2011 ISBN 978 1 84206 326 2 EQUALITY AND HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION RESEARCH REPORT SERIES The Equality and Human Rights Commission Research Report Series publishes research carried out for the Commission by commissioned researchers. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Commission. The Commission is publishing the report as a contribution to discussion and debate. Please contact the Research team for further information about other Commission research reports, or visit our website: Research Team Equality and Human Rights Commission Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0161 829 8500 Website: www.equalityhumanrights.com You can download a copy of this report as a PDF from our website: www.equalityhumanrights.com If you require this publication in an alternative format, please contact the Communications Team to discuss your needs at: [email protected] Contents Page Tables and figures i Acknowledgements ii Executive summary v 1. Background 1 1.1 Why is diversity in representation important? 2 1.2 Scope of the research 3 1.3 Researching diversity and inter-sectionality 4 1.4 Self-identification and representation 5 1.5 Understanding barriers and pathways 6 1.6 Chronically excluded groups 7 1.7 Structure of the report 8 2. -

Turn Back Time: the Family

TURN BACK TIME: THE FAMILY In October 2011, my lovely wife, Naomi, responded to an advert from TV production company Wall to Wall. Their assistant producer, Caroline Miller, was looking for families willing to take part in a living history programme. They wanted families who were willing to live through five decades of British history. At the same time, they wanted to retrace the history of those families to understand what their predecessors would have been doing during each decade. Well, as you may have already guessed, Wall to Wall selected the Goldings as one of the five families to appear in the programme. Shown on BBC1 at 9pm from Tuesday 26th June 2012, we were honoured and privileged to film three of the five episodes. As the middle class family in the Edwardian, inter war and 1940s periods, we quite literally had the most amazing experience of our lives. This page of my blog is to share our experiences in more detail – from selection, to the return to normal life! I have done this in parts, starting with ‘the selection process’ and ending with the experience of another family. Much of what you will read was not shown on TV, and may answer some of your questions (those of you who watched it!!). I hope you enjoy reading our story. Of course, your comments are very welcome. PART 1 – THE SELECTION PROCESS I will never forget the moment when I got home from work to be told by Naomi that she had just applied for us to be part of a TV programme. -

List of Goods Produced by Child Labor Or Forced Labor a Download Ilab’S Sweat & Toil and Comply Chain Apps Today!

2018 LIST OF GOODS PRODUCED BY CHILD LABOR OR FORCED LABOR A DOWNLOAD ILAB’S SWEAT & TOIL AND COMPLY CHAIN APPS TODAY! Browse goods Check produced with countries' child labor or efforts to forced labor eliminate child labor Sweat & Toil See what governments 1,000+ pages can do to end of research in child labor the palm of Review laws and ratifications your hand! Find child labor data Explore the key Discover elements best practice of social guidance compliance systems Comply Chain 8 8 steps to reduce 7 3 4 child labor and 6 forced labor in 5 Learn from Assess risks global supply innovative and impacts company in supply chains chains. examples ¡Ahora disponible en español! Maintenant disponible en français! B BUREAU OF INTERNATIONAL LABOR AFFAIRS How to Access Our Reports We’ve got you covered! Access our reports in the way that works best for you. ON YOUR COMPUTER All three of the USDOL flagship reports on international child labor and forced labor are available on the USDOL website in HTML and PDF formats, at www.dol.gov/endchildlabor. These reports include the Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor, as required by the Trade and Development Act of 2000; the List of Products Produced by Forced or Indentured Child Labor, as required by Executive Order 13126; and the List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor, as required by the Trafficking Victims Protection Reauthorization Act of 2005. On our website, you can navigate to individual country pages, where you can find information on the prevalence and sectoral distribution of the worst forms of child labor in the country, specific goods produced by child labor or forced labor in the country, the legal framework on child labor, enforcement of laws related to child labor, coordination of government efforts on child labor, government policies related to child labor, social programs to address child labor, and specific suggestions for government action to address the issue. -

Power of Women in Family Practise

Power of Women in Family Practise It was in the late 70s when Debra Boyce was inspired listening to Dr. Joyce Barret of Peterborough deliver a presentation to an eager group of students at Thomas A. Stewart. Followed by the encouragement of her trusted teachers to follow a career in science or medicine, she went on to pursue her medical degree at the University of Toronto in 1988 and start a family practise in her hometown of Peterborough. “After graduation from U of T I did my residency in Family Medicine in Ottawa,” says Dr. Boyce. “My husband had secured a job in Peterborough and so I returned home after my residency. I filled in for other family doctors for a few months and then started a shared practice with Dr. Barbara Gow. We were soon joined by Dr. Sheila Alexander and we had a busy family practice with primary care obstetrics. We also had our own children in those first few years – 12 children! – between the doctors and our staff! My husband also worked shifts and nights and when I look back on those busy times with small children it was occasionally frantic. When PRHC administration created the medical director positions I took on the position for Women and Children’s Services for several years and worked with a terrific team there, too. I continued to serve on various committees and take on project work at the hospital, Hospice Peterborough and my children’s schools. Family physicians were facing greater and greater challenges meeting the needs of the community, people without family doctors and the growing complexity of medical problems. -

PUBLIC TRANSPORT (The Association Is Grateful to Alan J

1 PUBLIC TRANSPORT (The Association is grateful to Alan J. Sutcliffe for compiling this section for the website.) Services should be checked with the relevant operator. All rail services shown apply until 13 December 2014. Seasonal bus services end in mid October in the case of most Sunday Dalesbus services though some 874 services continue all year. Additional and altered services will be shown when details become available. Leeds to Ilkley by train Mon-Sat. dep. 0602, 0634(SX), 0702, 0729(SX), 0735(SX), 0802, 0832(SO), 0835(SX), 0902 then at 02 and 32 mins past each hour until 1702, 1716(SX), 1732 (SO) 1734(SX), 1747(SX), 1802, 1832, 1902, 1933, 2003, 2106, 2206, 2315 (SO Sat only, SX except Sat). Sun. dep. 0912 then at 12 mins past each hour until 2212, 2316. by bus First Leeds service X84 from Leeds City Bus Station (15 mins walk from Leeds Station) via Otley. Mon-Fri. dep 0640,0705, 0755 then at 35 and 55 mins past each hour until 1655, 1745, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Sat. dep 0615, 0715, 0745, 0805, then at 35 and 55 mins past each hour until 1735, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Sun. dep 0710, 0800, 0910 then at 10 and 40 mins past each hour until 1610, 1710, 1805, 1905, 2005, 2115, 2215. Trains from Bradford Forster Square to Ilkley Mon-Fri dep 0615, 0644, 0711, 0745, 0816, then at 16 and 46 mins past each hour until 1616, 1644, 1717, 1746, 1811, 1846, 1941, 2038, 2138, 2238, 2320. Sat dep 0615, 0715, 0816, then at 16 and 46 mins past each hour until 1616, 1644, 1716, 1746, 1816, 1846, 1941, 2038, 2138, 2238, 2320.