Law ' S Judgement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tort Law Notes

https://www.uninote.co.uk/vendor/kings-llb-student/ All rights reserved to the author. Tort Law Notes Part 1 out of 2 [127 pages] Contents: Intentional Interferences with the Person + Defences Occupiers’ Liability Nuisance + The Tort in Rylands v Fletcher Remedies Vicarious Liability 1 https://www.uninote.co.uk/vendor/kings-llb-student/ All rights reserved to the author. Intentional Interferences with the Person Who can sue whom, in what tort, for what damage and are there any defences? Causes of Action Trespass to the person is an intentional tort = the conduct must be deliberate. It is the act and not the injury that has to be intentional, D does not need to intend to commit a tort or cause harm. Trespass is actionable without proof of damage. Letang v Cooper [1965] QB 232 Patch of land/grass used as car park for a hotel. Claimant sunbathing on that patch, car ran over her. Suffered severe injuries to her legs, she sued. It mattered whether she was bringing her claim in the tort of battery and in the tort of negligence because of the limitation period. This no longer applies because of new statute (private law 6 years, personal injury 3 years). Lord Denning: “We divide the causes of action now according as the defendant did the injury intentionally or unintentionally.” Intentionally = trespass to the person Unintentionally = negligence ASSAULT An assault is an act which causes another person to apprehend the infliction of immediate, unlawful, force on his person. Assault protects the right not to be put in fear of unlawful invasion of our integrity. -

Principles of Tort Law Rachael Mulheron Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72764-8 — Principles of Tort Law Rachael Mulheron Frontmatter More Information Principles of Tort Law Presenting the law of Tort as a body of principles, this authoritative textbook leads students to an incisive and clear understanding of the subject. Each tort is carefully structured and examined within a consistent analytical framework that guides students through its preconditions, elements, defences, and remedies. Clear summaries and comparisons accompany the detailed exposition, and further support is provided by numerous diagrams and tables, which clarify complex aspects of the law. Critical discussion of legal judgments encourages students to develop strong analytical and case-reading skills, while key reform pro posals and leading cases from other jurisdictions illustrate different potential solutions to conun- drums in Tort law. A rich companion website, featuring semesterly updates, and ten additional chapters and sections on more advanced areas of Tort law, completes the learning package. Written speciically for students, the text is also ideal for practitioners, litigants, policy-makers, and law reformers seeking a comprehensive and accurate understanding of the law. Rachael Mulheron is Professor of Tort Law and Civil Justice at the School of Law, Queen Mary University of London, where she has taught since 2004. Her principal ields of academic research concern Tort law and class actions jurisprudence. She publishes regularly in both areas, and has frequently assisted law reform commissions, government departments, and law irms on Tort-related and collective redress- related matters. Professor Mulheron also undertakes extensive law reform work, previously as a member of the Civil Justice Council of England and Wales, and now as Research Consultant for that body. -

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane LLB (Hons), Dip LP, PGCE, LLM A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Richard Whitecross and Dr Sandra Watson, for giving me their time, guidance and assistance in the writing up of my PhD Critical Appraisal of published works. I am indebted to my parents, Irene and Dennis, for a lifetime of love and support. Many thanks are also due to my family and friends for their ongoing care and companionship. In particular, I am very grateful to Professors Elaine E Sutherland and John P Grant for reading through and commenting on my section on Traditional Legal Research Methods. My deepest thanks are owed to my husband, Ross, who never fails in his love, encouragement and practical kindness. I confirm that the published work submitted has not been submitted for another award. ………………………………………… Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane Citations and references have been drafted with reference to the University’s Research Degree Reference Guide 2 CONTENTS VOLUME I Abstract: PhD by Published Works Page 8 List of Evidence in Support of Thesis Page 9 Thesis Introduction Page 10 (I) An Era of Change in the Individual’s Rights, Status and Capacity in Scots Law (II) Conceptual Framework of Critical Analysis: Rights, -

Oxford University Undergraduate Law Journal ~

THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE LAW JOURNAL ~ ISSUE EIGHT TRINITY TERM 2019 2 The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Editorial or Honorary Board of the Oxford University Undergraduate Law Journal. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this journal is correct, the Editors and the authors cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions, or for any consequences resulting therefrom. © 2019 Individual authors ISSUE VIII (2019) 3 THE EIGHTH EDITORIAL BOARD EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Kenneth Chong Anna Yamaoka-Enkerlin Magdalen College Pembroke College EDITORS Adrian Burbie Niamh Kelly Merton College Merton College SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITORS Tim Koch Oskar Sherry Jesus College Lady Margaret Hall ASSOCIATE EDITORS Jonas Atmaz Al- Eliza Chee William Chen Sibaie University College Harris Manchester St John’s College College Ee Hsiun Chong Edwin Ewing Bruno Ligas- St John’s College St John’s College Rucinski Christ Church Francesca Parkes Ming Zee Tee George Twinn Corpus Christi Jesus College St Hilda’s College College Joshua Wang St Catherine’s College SPONSORSHIP OFFICER PUBLICITY OFFICER Isadora Janssen Kulsimran Sidhu Merton College Mansfield College 4 THE HONORARY BOARD Sir Nicolas Bratza Professor Michael Bridge Donald Findlay QC Professor Christopher Forsyth Ian Gatt QC The Rt Hon. the Lord Judge The Rt Hon. the Lord Kerr of Tonaghmore Michael Mansfield QC The Rt Hon. the Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury The Rt Hon. the Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers The Lord Pannick -

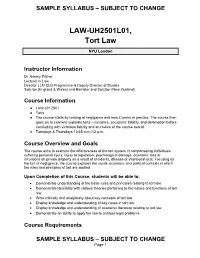

Torts ● the Course Starts by Looking at Negligence and How It Works in Practice

SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE LAW-UH2501L01, Tort Law NYU London Instructor Information Dr Jeremy Pilcher Lecturer in Law Director LLM QLD Programme & Deputy Director of Studies Solicitor (England & Wales) and Barrister and Solicitor (New Zealand) Course Information ● LAW-UH 2501 ● Torts ● The course starts by looking at negligence and how it works in practice. The course then goes on to examine separate torts – nuisance, occupiers’ liability, and defamation before concluding with vicarious liability and an review of the course overall. ● Tuesdays & Thursdays 10:45 a.m.-12 p.m. Course Overview and Goals The course aims to examine the effectiveness of the tort system in compensating individuals suffering personal injury, injury to reputation, psychological damage, economic loss or incursions on private property as a result of accidents, disease or intentional acts. Focusing on the tort of negligence, the course explores the social, economic and political contexts in which the rules and principles of tort are applied. Upon Completion of this Course, students will be able to: • Demonstrate understanding of the basic rules and principles relating to tort law • Demonstrate familiarity with various theories pertaining to the nature and functions of tort law • Write critically and analytically about key concepts of tort law • Display knowledge and understanding of key cases in tort law • Display knowledge and understanding of academic literature relating to tort law • Demonstrate an ability to apply the law to analyse legal problems Course Requirements SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE Page 1 SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE Class Participation • The module will be taught through lectures and are intended to provide a broad overview, or map of a subject area which will then be developed through independent study. -

Petition for Appointment of a Prosecutor Pro Tempore by Jane Doe 1, Jane Doe 2, Jane Doe 3, and Jane Doe 4 ______

Original Action No. _________-SC IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF UTAH __________________ IN RE: PETITION FOR APPOINTMENT OF A PROSECUTOR PRO TEMPORE BY JANE DOE 1, JANE DOE 2, JANE DOE 3, AND JANE DOE 4 __________________ PETITION FOR APPOINTMENT OF PROSECUTOR PRO TEMPORE __________________ On Original Jurisdiction to the Utah Supreme Court __________________ Paul G. Cassell (6078) UTAH APPELLATE CLINIC S.J. Quinney College of Law at the University of Utah 383 S. University St. Salt Lake City, Utah 84112 (801) 585-5202 [email protected] Heidi Nestel (7948) Bethany Warr (14548) UTAH CRIME VICTIMS’ LEGAL CLINIC 3335 South 900 East, Suite 200 Salt Lake City, Utah 84106 [email protected] [email protected] Attorneys for Jane Doe 1, Jane Doe 2, Jane Doe 3, and Jane Doe 4 Additional counsel on the following page __________________ Full Briefing and Oral Argument Requested on State Constitutional Law Issues of First Impression Additional Counsel Margaret Garvin (Oregon Bar 044650) NATIONAL CRIME VICTIM LAW INSTITUTE at the Lewis and Clark Law School 1130 S.W. Morrison Street, Suite 200 Portland, Oregon 97205 [email protected] (pro hac vice application to be filed) (law schools above are contact information only – not to imply institutional endorsement) Gregory Ferbrache (10199) FERBRACHE LAW, PLLC 2150 S. 1300 E. #500 Salt Lake City, Utah 84106 [email protected] (801) 440-7476 Aaron H. Smith (16570) STRONG & HANNI 9350 South 150 East, Suite 820 Sandy, Utah 84070 [email protected] (801) 532-7080 Attorneys for Jane Doe 1, Jane Doe 2, Jane Doe 3, and Jane Doe 4 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. -

The Many Faces of the Reasonable Person

The Many Faces of the Reasonable Person JOHN GARDNER* 1. Introducing the reasonable person The reasonable person (once known as the ‘reasonable man’) is the longest-established of ‘the select group of personalities who inhabit our legal village and are available to be called upon when a problem arises that needs to be solved objectively.’1 These days, partly because of his runaway success as the common law’s helpmate, he has neighbours as diverse as the ordinary prudent man of business,2 the officious bystander,3 the reasonable juror properly directed, and the fair-minded and informed observer.4 All of these colourful characters, and many others besides,5 provide important standard-setting services to the law. But none more so than the village’s most venerable resident. * Professor of Jurisprudence, University of Oxford. For valuable comments and criticisms I am grateful to Claire Finkelstein, Heidi Li Feldman, Scott Hershovitz, Greg Klass, Lewis Kornhauser, John Mikhail, Peter Mirfield, Mark Murphy, Dan Priel, Henry Richardson, Paul Roberts, Prince Saprai, and most of all Marcia Baron. Also to audiences at the University of Nottingham, Georgetown University, and the University of Frankfurt. 1 Helow v Advocate General [2008] 1 WLR 2416 at 2417-8 per Lord Hope. 2 Speight v Gaunt (1883) LR 9 App Cas 1 at 19-20 per Lord Blackburn. 3 Shirlaw v Southern Foundries [1939] 2 KB 206 at 227 per MacKinnon LJ. 4 Webb v The Queen (1994) 181 CLR 41 at 52 per Mason CJ and McHugh J. 5 For news of a recent arrival from the EU (‘the reasonably well-informed and normally diligent tenderer’) see Healthcare at Home Ltd v The Common Services Agency [2014] UKSC 49. -

What Is Tort?

CHAPTER ONE What is tort? SUMMARY The law of tort provides remedies in a wide variety of situations. Overall it has a rather tangled appearance. But there is some underlying order. This chapter tries to explain some of that order. It also reviews the main functions of the law of tort. These include deterring unsafe behaviour, giving a just response to wrongdoing, and spreading the cost of accidents broadly. The chapter then introduces two major institutions within the law of tort: the tort of negligence and the role played by statute law. Tort: Part of the law of civil wrongs 1.1 Where P sues D for a tort, P is complaining of a wrong suffered at D’s hands. The remedy P is claiming is usually a money payment. So proceedings in tort are different from criminal proceedings: in a criminal court, typically, it is not the victim of the wrong who starts the proceedings, but some official prosecutor. The remedy will also be different. A criminal court may decide that D should pay a sum of money, but if it does, the money will usually be forfeited to the state, rather than to P. (For this reason, some say that tort is about compensating P, whereas the criminal law is about punishing D. But as you will see, this begs various questions about what ‘punishment’ means; I will soon return to this issue.) This is the most basic defining feature of tort. It is a civil, not a criminal, action. The claim is pursued in a civil court, and civil procedure is very different from criminal procedure. -

Lawexpress Tort Law/6E

Tried and tested by undergraduate ‘. defi nitely the best revision guides on the market.’ law students across the UK. Nayiri Keshishi, law student 94% of students polled agree that Law Express helps them to revise effectively and TORT LAW take exams with confi dence. Make your answer stand out with , the UK’s bestselling law revision series. > Review the key cases, statutes and legal terms you need to 6th edition know for your exam. BEST > Improve your exam performance with helpful advice on SELLING effective revision. > UNDERSTAND QUICKLY FINCH AND FAFINSKI REVISION > Maximise your marks with tips for advanced thinking and > REVISE EFFECTIVELY SERIES further debate. > TAKE EXAMS WITH CONFIDENCE > Avoid losing marks by understanding common pitfalls. > answering sample questions and fi nd guidance for Practise 6th edition structuring strong answers. > Hone your exam technique further with additional study materials on the companion website. TORT LAW www.pearsoned.co.uk/lawexpress £12.99 EMILY FINCH AND STEFAN FAFINSKI Emily Finch and Stefan Fafi nski are authors of bestselling, student-friendly resources and their website: www.pearson-books.com www.fi nchandfafi nski.com CVR_FINC6880_06_SE_CVR.indd 1 02/03/2016 10:52 TORAW T L A01_FINC6880_06_SE_FM.indd 1 3/7/16 1:14 PM Tried and tested Law Express has been helping UK law students to revise since 2009 and its power is proven. A recent survey * shows that: ■ 94% think that Law Express helps them to revise effectively and take exams with confidence. ■ 88% agree Law Express helps them to understand key concepts quickly. Individual students attest to how the series has supported their revision: ‘Law Express are my go-to guides. -

Reforming the English Law on Parental Liability: a Comparison with the French Experience

Durham E-Theses Reforming the English law on parental liability: a comparison with the French experience. McIvor, Claire Marie How to cite: McIvor, Claire Marie (1999) Reforming the English law on parental liability: a comparison with the French experience., Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4589/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Reforming the English Law on Parental Liability: A Comparison With The French Experience. Claire Marie Mclvor English law has demonstrated itself to be particularly hostile to the idea of holding parents tortiously liable for the acts of their children. It deals with allegations ofparental negligence with a degree of leniency that, arguably, defies all rational justification. In advocating reform, the primary objective of this thesis is to put forward a proposal for a new regime of liability that obliges parents to take much greater legal responsibility for their children's conduct. -

In Re: Petition for Appointment of a Prosecutor Pro Tempore by Jane

SJ Quinney College of Law, University of Utah Utah Law Digital Commons Utah Law Faculty Scholarship Utah Law Scholarship 10-2018 In Re: Petition for Appointment of a Prosecutor Pro Tempore by Jane Doe 1, Jane Doe 2, Jane Doe 3, and Jane Doe 4 : Petition for Appointment of Prosecutor Pro Tempore Paul Cassell S.J. Quinney College of Law, University of Utah, [email protected] Heidi Nestel Utah Crime Victims' Legal Clinic Bethany Warr Utah Crime Victims' Legal Clinic Margaret Garvin Defense Advisory Committee on Investigation, Prosecution, and Defense or Sexual Assault in the Armed Forces (DAC-IPAD) Gregory Ferbrache Ferbrache Law, PLLC See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship Part of the Criminal Law Commons Recommended Citation Cassell, Paul; Nestel, Heidi; Warr, Bethany; Garvin, Margaret; Ferbrache, Gregory; and Hanni, Aaron H., "In Re: Petition for Appointment of a Prosecutor Pro Tempore by Jane Doe 1, Jane Doe 2, Jane Doe 3, and Jane Doe 4 : Petition for Appointment of Prosecutor Pro Tempore" (2018). Utah Law Faculty Scholarship. 134. https://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship/134 This Brief is brought to you for free and open access by the Utah Law Scholarship at Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Utah Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Paul Cassell, Heidi Nestel, Bethany Warr, Margaret Garvin, Gregory Ferbrache, and Aaron H. Hanni This brief is available at Utah Law Digital Commons: https://dc.law.utah.edu/scholarship/134 Original Action No. -

The Standard of the Reasonable Person in Determining Negligencer AHMED– Comparative Conclusionsper / PELJ 2021 (24) 1

The Standard of the Reasonable Person in Determining NegligenceR AHMED– Comparative ConclusionsPER / PELJ 2021 (24) 1 R Ahmed* Online ISSN 1727-3781 Abstract Pioneer in peer -reviewed, open access online law publications The standard of the reasonable person or its equivalent, in general, is used in many jurisdictions to determine fault in the form of negligence. Although the standard is predominantly objective it is also subjective in Author that the subjective attributes of the person against whom the standard applies as well as the subjective circumstances present at the time of Raheel Ahmed the delict or tort lend themselves to an objective-subjective application. In South African law, before a person can be judged according to the Affiliation standard of the reasonable person, the person must first be held accountable. If a person cannot be held accountable, then the standard University of South Africa does not apply at all. Email The general standard of the reasonable person cannot be applied to children, the elderly, persons with physical disabilities, persons with mental impairments or experts. Therefore, depending on the subjective [email protected] attributes of the person against whom the standard is being applied, the standard may have to be adjusted accordingly. The general standard of Date Submission the reasonable person would be raised when dealing with experts, for instance, and lowered when dealing with persons with physical 14 July 2020 disabilities. Date Revised This contribution considers whether the current application of the standard of the reasonable person in South African law is satisfactory 26 March 2021 when applied generally to all persons, no matter their age, experience, gender, physical disability and cognitive ability.