The Many Faces of the Reasonable Person

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keith Stanton and the Law of Professional Negligence

Oliphant, K. (2017). Editorial: Keith Stanton and the Law of Professional Negligence. Tottel's Journal of Professional Negligence, 33, 61-71. https://www.bloomsburyprofessionalonline.com/view/journal_prof_negl /jpn33-2-A33ch002.xml Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the author accepted manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via Bloomsbury Professional at https://www.bloomsburyprofessionalonline.com/view/journal_prof_negl/jpn33-2- A33ch002.xml . Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Editorial ‘Keith Stanton and the Law of Professional Negligence’* Ken Oliphant, University of Bristol Introduction This issue of the journal takes the form of a Festschrift dedicated to Keith Stanton, professor of law at the University of Bristol, a leading light in the recognition and development of the law of professional negligence as a distinct legal category, and one of the founding editors of this journal. It comprises of revised versions of papers given at the seminar ‘Professional Negligence Law in the 21st Century’ at the University of Bristol Law School on 17 January 2017. The seminar was the second that the journal has sponsored since its acquisition by Bloomsbury Professional in XXXX, the first (in 2015) commemorating the 30th anniversary of the journal’s first publication.1 The extent of Keith’s contribution to the law of professional negligence, tort law more widely, and the study of law in university in general, provides more than ample justification for the dedication of this special issue to him. -

The Legal Structure of UK Biobank: Private Law for Public Goods?

The Legal Structure of UK Biobank: Private Law for Public Goods? By: Jessica Lauren Bell A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield School of Law February 2016 Abstract Population biobanks hold promise for improving the health of future generations by providing researchers with a resource of both human samples and data to investigate the linkages between genes, lifestyle and environment in population health. Widespread concern has been expressed in academic and policy literature as to the ongoing ethical, legal and social challenges that are raised by population biobanks, by virtue of their longitudinal nature and broadly set research aims. To address these challenges, and to balance private interests of the individuals who donate to biobanks, with the public benefit that is believed to derive from the establishment of biobanks, some countries have specifically legislated to establish national biobanks. Alternatively, UK Biobank has been incorporated as a charitable corporation. Potentially, this private legal structure diminishes the public accountability of the project, as well as the protection of donors from personal harm. This thesis analyses the multi-layered nexus of laws within which UK Biobank is embedded and shows the tensions that are associated with using a private legal structure to secure public objectives. UK Biobank is in unchartered legal territory on a number of levels, and this thesis posits UK Biobank as a timely example of a large- scale organisation whose model straddles the public/private divide in law and invites an eclectic mix of corporate, public, charity, contract and tort lawyers into a conversation with ethicists, scientists, policy experts and the public to consider how to effectively progress population health via biobanking. -

Tort Law Notes

https://www.uninote.co.uk/vendor/kings-llb-student/ All rights reserved to the author. Tort Law Notes Part 1 out of 2 [127 pages] Contents: Intentional Interferences with the Person + Defences Occupiers’ Liability Nuisance + The Tort in Rylands v Fletcher Remedies Vicarious Liability 1 https://www.uninote.co.uk/vendor/kings-llb-student/ All rights reserved to the author. Intentional Interferences with the Person Who can sue whom, in what tort, for what damage and are there any defences? Causes of Action Trespass to the person is an intentional tort = the conduct must be deliberate. It is the act and not the injury that has to be intentional, D does not need to intend to commit a tort or cause harm. Trespass is actionable without proof of damage. Letang v Cooper [1965] QB 232 Patch of land/grass used as car park for a hotel. Claimant sunbathing on that patch, car ran over her. Suffered severe injuries to her legs, she sued. It mattered whether she was bringing her claim in the tort of battery and in the tort of negligence because of the limitation period. This no longer applies because of new statute (private law 6 years, personal injury 3 years). Lord Denning: “We divide the causes of action now according as the defendant did the injury intentionally or unintentionally.” Intentionally = trespass to the person Unintentionally = negligence ASSAULT An assault is an act which causes another person to apprehend the infliction of immediate, unlawful, force on his person. Assault protects the right not to be put in fear of unlawful invasion of our integrity. -

Libel As Malpractice: News Media Ethics and the Standard of Care

Fordham Law Review Volume 53 Issue 3 Article 3 1984 Libel as Malpractice: News Media Ethics and the Standard of Care Todd F. Simon Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Todd F. Simon, Libel as Malpractice: News Media Ethics and the Standard of Care, 53 Fordham L. Rev. 449 (1984). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol53/iss3/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LIBEL AS MALPRACTICE: NEWS MEDIA ETHICS AND THE STANDARD OF CARE TODD F. SIMON* INTRODUCTION D OCTORS, lawyers, and journalists share a strong common bond: They live in fear of being haled into court where the trier of fact will pass judgment on how they have performed their duties. When the doc- tor or lawyer is sued by a patient or client, it is a malpractice case.I The standard by which liability is determined is whether the doctor or lawyer acted with the knowledge, skill and care ordinarily possessed and em- ployed by members of the profession in good standing.' Accordingly, if * Assistant Professor and Director, Journalism/Law Institute, Michigan State Uni- versity School of Journalism; Member, Nebraska Bar. 1. W. Keeton, D. Dobbs, R. Keeton & D. Owen, Prosser and Keeton on Torts, § 32, at 185-86 (5th ed. -

The United States Supreme Court Adopts a Reasonable Juvenile Standard in J.D.B. V. North Carolina

THE UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT ADOPTS A REASONABLE JUVENILE STANDARD IN J.D.B. V NORTH CAROLINA FOR PURPOSES OF THE MIRANDA CUSTODY ANALYSIS: CAN A MORE REASONED JUSTICE SYSTEM FOR JUVENILES BE FAR BEHIND? Marsha L. Levick and Elizabeth-Ann Tierney∗ I. Introduction II. The Reasonable Person Standard a. Background b. The Reasonable Person Standard and Children: Kids Are Different III. Roper v. Simmons and Graham v. Florida: Embedding Developmental Research Into the Court’s Constitutional Analysis IV. From Miranda v. Arizona to J.D.B. v. North Carolina V. J.D.B. v. North Carolina: The Facts and The Analysis VI. Reasonableness Applied: Justifications, Defenses, and Excuses a. Duress Defenses b. Justified Use of Force c. Provocation d. Negligent Homicide e. Felony Murder VII. Conclusion I. Introduction The “reasonable person” in American law is as familiar to us as an old shoe. We slip it on without thinking; we know its shape, style, color, and size without looking. Beginning with our first-year law school classes in torts and criminal law, we understand that the reasonable person provides a measure of liability and responsibility in our legal system.1 She informs our * ∗Marsha L. Levick is the Deputy Director and Chief Counsel for Juvenile Law Center, a national public interest law firm for children, based in Philadelphia, Pa., which Ms. Levick co-founded in 1975. Ms. Levick is a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University School of Law. Elizabeth-Ann “LT” Tierney is the 2011 Sol and Helen Zubrow Fellow in Children's Law at the Juvenile Law Center. -

Principles of Tort Law Rachael Mulheron Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-72764-8 — Principles of Tort Law Rachael Mulheron Frontmatter More Information Principles of Tort Law Presenting the law of Tort as a body of principles, this authoritative textbook leads students to an incisive and clear understanding of the subject. Each tort is carefully structured and examined within a consistent analytical framework that guides students through its preconditions, elements, defences, and remedies. Clear summaries and comparisons accompany the detailed exposition, and further support is provided by numerous diagrams and tables, which clarify complex aspects of the law. Critical discussion of legal judgments encourages students to develop strong analytical and case-reading skills, while key reform pro posals and leading cases from other jurisdictions illustrate different potential solutions to conun- drums in Tort law. A rich companion website, featuring semesterly updates, and ten additional chapters and sections on more advanced areas of Tort law, completes the learning package. Written speciically for students, the text is also ideal for practitioners, litigants, policy-makers, and law reformers seeking a comprehensive and accurate understanding of the law. Rachael Mulheron is Professor of Tort Law and Civil Justice at the School of Law, Queen Mary University of London, where she has taught since 2004. Her principal ields of academic research concern Tort law and class actions jurisprudence. She publishes regularly in both areas, and has frequently assisted law reform commissions, government departments, and law irms on Tort-related and collective redress- related matters. Professor Mulheron also undertakes extensive law reform work, previously as a member of the Civil Justice Council of England and Wales, and now as Research Consultant for that body. -

Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation

STATE Q&A Fraud: District of Columbia by Robert Van Kirk, Williams & Connolly LLP, with Practical Law Commercial Litigation Status: Law stated as of 16 Mar 2021 | Jurisdiction: District of Columbia, United States This document is published by Practical Law and can be found at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/w-029-0846 Request a free trial and demonstration at: us.practicallaw.tr.com/about/freetrial A Q&A guide to fraud claims under District of Columbia law. This Q&A addresses the elements of actual fraud, including material misrepresentation and reliance, and other types of fraud claims, such as fraudulent concealment and constructive fraud. Elements Generally – nondisclosure of a material fact when there is a duty to disclose (Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (D.C.) v. Jericho Baptist Church Ministries, Inc. (Md.), 1. What are the elements of a fraud claim in 223 F. Supp. 3d 1, 10 (D.D.C. 2016) (applying District your jurisdiction? of Columbia law)). To state a claim of common law fraud (or fraud in the (Sundberg v. TTR Realty, LLC, 109 A.3d 1123, 1131 inducement) under District of Columbia law, a plaintiff (D.C. 2015).) must plead that: • A material misrepresentation actionable in fraud • The defendant made: must be consciously false and intended to mislead another (Sarete, Inc. v. 1344 U St. Ltd. P’ship, 871 A.2d – a false statement of material fact (see Material 480, 493 (D.C. 2005)). A literally true statement Misrepresentation); that creates a false impression can be actionable in fraud (Jacobson v. Hofgard, 168 F. Supp. 3d 187, 196 – with knowledge of its falsity; and (D.D.C. -

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law

A Critical Evaluation of the Rights, Status and Capacity of Distinct Categories of Individuals in Underdeveloped and Emerging Areas of Law Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane LLB (Hons), Dip LP, PGCE, LLM A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Edinburgh Napier University, for the award of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 1 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisors, Dr Richard Whitecross and Dr Sandra Watson, for giving me their time, guidance and assistance in the writing up of my PhD Critical Appraisal of published works. I am indebted to my parents, Irene and Dennis, for a lifetime of love and support. Many thanks are also due to my family and friends for their ongoing care and companionship. In particular, I am very grateful to Professors Elaine E Sutherland and John P Grant for reading through and commenting on my section on Traditional Legal Research Methods. My deepest thanks are owed to my husband, Ross, who never fails in his love, encouragement and practical kindness. I confirm that the published work submitted has not been submitted for another award. ………………………………………… Lesley-Anne Barnes Macfarlane Citations and references have been drafted with reference to the University’s Research Degree Reference Guide 2 CONTENTS VOLUME I Abstract: PhD by Published Works Page 8 List of Evidence in Support of Thesis Page 9 Thesis Introduction Page 10 (I) An Era of Change in the Individual’s Rights, Status and Capacity in Scots Law (II) Conceptual Framework of Critical Analysis: Rights, -

In the Supreme Court of Mississippi No. 2012-Ca-02010

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF MISSISSIPPI NO. 2012-CA-02010-SCT BRONWYN BENOIST PARKER v. WILLIAM DEAN BENOIST AND WILLIAM D. BENOIST, INDIVIDUALLY, AND IN HIS CAPACITY OF EXECUTOR OF THE ESTATE OF BILLY DEAN “B.D.” BENOIST, DECEASED v. BRONWYN BENOIST PARKER ON MOTION FOR REHEARING DATE OF JUDGMENT: 02/20/2012 TRIAL JUDGE: HON. PERCY L. LYNCHARD, JR. TRIAL COURT ATTORNEYS: GOODLOE TANKERSLEY LEWIS AMANDA POVALL TAILYOUR GRADY F. TOLLISON, JR. REBECCA B. COWAN KRISTEN E. BOYDEN COURT FROM WHICH APPEALED: YALOBUSHA COUNTY CHANCERY COURT ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLANT: GOODLOE TANKERSLEY LEWIS AMANDA POVALL TAILYOUR ATTORNEYS FOR APPELLEE: GRADY F. TOLLISON, JR. TAYLOR H. WEBB REBECCA B. COWAN NATURE OF THE CASE: CIVIL - WILLS, TRUSTS, AND ESTATES DISPOSITION: ON DIRECT APPEAL: AFFIRMED IN PART; REVERSED AND RENDERED IN PART; REVERSED AND REMANDED IN PART ON CROSS-APPEAL: AFFIRMED - 02/19/2015 MOTION FOR REHEARING FILED: 09/25/2014 MANDATE ISSUED: BEFORE WALLER, C.J., KITCHENS AND CHANDLER, JJ. KITCHENS, JUSTICE, FOR THE COURT: ¶1. Bronwyn Benoist Parker’s motion for rehearing is granted. The original opinion is withdrawn and this opinion is substituted therefor. ¶2. Parker and William Benoist are siblings who litigated the will of their father, Billy Dean “B.D.” Benoist, in the Chancery Court of Yalobusha County. In 2010, B.D. executed a will which significantly altered the distributions provided by a previous will that B.D. had executed in 1998. Bronwyn alleged that William had unduly influenced their father, who was suffering from dementia and drug addiction, into making the new will, which included a forfeiture clause that revoked benefits to any named beneficiary who contested the will. -

Oxford University Undergraduate Law Journal ~

THE OXFORD UNIVERSITY UNDERGRADUATE LAW JOURNAL ~ ISSUE EIGHT TRINITY TERM 2019 2 The views expressed by the contributors are not necessarily those of the Editorial or Honorary Board of the Oxford University Undergraduate Law Journal. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure that the information contained in this journal is correct, the Editors and the authors cannot accept any responsibility for any errors or omissions, or for any consequences resulting therefrom. © 2019 Individual authors ISSUE VIII (2019) 3 THE EIGHTH EDITORIAL BOARD EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Kenneth Chong Anna Yamaoka-Enkerlin Magdalen College Pembroke College EDITORS Adrian Burbie Niamh Kelly Merton College Merton College SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITORS Tim Koch Oskar Sherry Jesus College Lady Margaret Hall ASSOCIATE EDITORS Jonas Atmaz Al- Eliza Chee William Chen Sibaie University College Harris Manchester St John’s College College Ee Hsiun Chong Edwin Ewing Bruno Ligas- St John’s College St John’s College Rucinski Christ Church Francesca Parkes Ming Zee Tee George Twinn Corpus Christi Jesus College St Hilda’s College College Joshua Wang St Catherine’s College SPONSORSHIP OFFICER PUBLICITY OFFICER Isadora Janssen Kulsimran Sidhu Merton College Mansfield College 4 THE HONORARY BOARD Sir Nicolas Bratza Professor Michael Bridge Donald Findlay QC Professor Christopher Forsyth Ian Gatt QC The Rt Hon. the Lord Judge The Rt Hon. the Lord Kerr of Tonaghmore Michael Mansfield QC The Rt Hon. the Lord Neuberger of Abbotsbury The Rt Hon. the Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers The Lord Pannick -

Principles of Tort Law, Fourth Edition

PRINCIPLES OF TORT LAW Fourth Edition CP Cavendish Publishing Limited London • Sydney EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD PRINCIPLES OF LAW SERIES PROFESSOR PAUL DOBSON Visiting Professor at Anglia Polytechnic University PROFESSOR NIGEL GRAVELLS Professor of English Law, Nottingham University PROFESSOR PHILLIP KENNY Professor and Head of the Law School, Northumbria University PROFESSOR RICHARD KIDNER Professor at the Law Department, University of Wales, Aberystwyth In order to ensure that the material presented by each title maintains the necessary balance between thoroughness in content and accessibility in arrangement, each title in the series has been read and approved by an independent specialist under the aegis of the Editorial Board. The Editorial Board oversees the development of the series as a whole, ensuring a conformity in all these vital aspects. PRINCIPLES OF TORT LAW Fourth Edition Vivienne Harpwood, LLB, Barrister Reader in Law, Cardiff Law School CCPP Cavendish PublishingCavendish PublishingLimited Limited London • Sydney Fourth edition first published in Great Britain 2000 by Cavendish Publishing Limited, The Glass House, Wharton Street, London WC1X 9PX, United Kingdom. Telephone: +44 (0)20 7278 8000 Facsimile: +44 (0)20 7278 8080 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.cavendishpublishing.com © Harpwood, V2000 First edition 1993 Second edition 1996 Third edition 1997 Fourth edition 2000 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1P 9HE, UK, without the permission in writing of the publisher. -

Torts ● the Course Starts by Looking at Negligence and How It Works in Practice

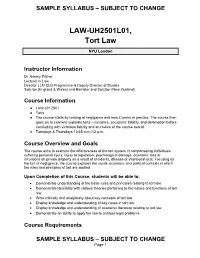

SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE LAW-UH2501L01, Tort Law NYU London Instructor Information Dr Jeremy Pilcher Lecturer in Law Director LLM QLD Programme & Deputy Director of Studies Solicitor (England & Wales) and Barrister and Solicitor (New Zealand) Course Information ● LAW-UH 2501 ● Torts ● The course starts by looking at negligence and how it works in practice. The course then goes on to examine separate torts – nuisance, occupiers’ liability, and defamation before concluding with vicarious liability and an review of the course overall. ● Tuesdays & Thursdays 10:45 a.m.-12 p.m. Course Overview and Goals The course aims to examine the effectiveness of the tort system in compensating individuals suffering personal injury, injury to reputation, psychological damage, economic loss or incursions on private property as a result of accidents, disease or intentional acts. Focusing on the tort of negligence, the course explores the social, economic and political contexts in which the rules and principles of tort are applied. Upon Completion of this Course, students will be able to: • Demonstrate understanding of the basic rules and principles relating to tort law • Demonstrate familiarity with various theories pertaining to the nature and functions of tort law • Write critically and analytically about key concepts of tort law • Display knowledge and understanding of key cases in tort law • Display knowledge and understanding of academic literature relating to tort law • Demonstrate an ability to apply the law to analyse legal problems Course Requirements SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE Page 1 SAMPLE SYLLABUS – SUBJECT TO CHANGE Class Participation • The module will be taught through lectures and are intended to provide a broad overview, or map of a subject area which will then be developed through independent study.