Moving with the Tides Page 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animal Adaptations

Animal Adaptations The Animal Adaptations program at Hatfield Marine Science Center is designed to be a 50- minute lab-based program for 3rd-12th grade students that examines marine organisms from three different habitats (sandy beach, rocky shore and estuary) and explores the many ways they are adapted to their particular environment. This lab focuses on the adaptations of several groups of marine animals including Mollusks, Crustaceans, and Echinoderms, and investigates how they differ depending on whether they are found in a sandy beach, rocky shore, or estuary environment. Students will work in small groups with a variety of live animals, studying individual characteristics and how these organisms interact with their environment and one another. Background Information The Oregon Coast is made up of a series of rocky shores, sandy beaches, and estuaries, all of which are greatly affected by fluctuating tides. Many of these areas are intertidal and are alternately inundated by seawater and exposed to air, wind, and dramatic changes in temperature and salinity. High tide floods these areas with cold, nutrient laden seawater, bringing food to organisms that live there in the form of plankton and detritus. Low tides often expose these organisms to the dangers of predation and desiccation. In addition to tidal effects, organisms that inhabit sandy beaches and rocky shores also have to deal with the physical stresses of pounding waves. Because of these harsh conditions, organisms have developed special adaptations that not only help them to survive but thrive in these environments. An adaptation is a physical or behavioral trait that helps a plant or animal survive in a specific environment or habitat. -

Seashore the SANDYSEASHORE the Soilisinfertile, Anditisoften Windy, Andsalty

SEASHORE DESCRIPTION The seashore is an area fi lled with an interesting mix of unique plants and animals that have adapted to cope with this environment. Living on the edge of the sea is not easy. The soil is infertile, and it is often windy, dry and salty. THE SANDY SEASHORE Along a sandy shore there are no large rocks, algae or tidal pools. The sandy seashore can be divided into four general zones: Intertidal, Pioneer, Fixed Dune and Scrub Woodland. 1. Intertidal Zone: Between the low tide and the high tide mark is the intertidal zone. When the tide goes out the creatures living in this zone are left stranded. They have to endure the heat of the sun and the higher salinity of the water resulting from evaporation. Notice the many small holes on a sandy beach; they are the doorways to the homes of many animals which burrow under the sand where it is cooler. Some of Ecosystems of The Bahamas the creatures living in this zone are sea worms, sand fl eas and sand crabs. 2. Pioneer Zone: So named because it is where the fi rst plants to try to grow over sand. These plants must adapt to loose, shifting sand and poor soil. There is no protection from wind or salt spray. Plants here are usually low growing vines with waxy leaves. Some plants found in the pioneer zone are Purple seaside bean (C. rosea), Saltwort (Batis maritima), Goat's foot (Ipomea pes-caprae), and Sea purslane (Sesuvium portulacastrum). 3. Fixed Dune Zone: The next zone is the fi xed dune, so named because as the plants in the pioneer zone grip the sand around their roots and make the beach more stable, the sand mounds up into small humps or dunes. -

PROTISTS Shore and the Waves Are Large, Often the Largest of a Storm Event, and with a Long Period

(seas), and these waves can mobilize boulders. During this phase of the storm the rapid changes in current direction caused by these large, short-period waves generate high accelerative forces, and it is these forces that ultimately can move even large boulders. Traditionally, most rocky-intertidal ecological stud- ies have been conducted on rocky platforms where the substrate is composed of stable basement rock. Projec- tiles tend to be uncommon in these types of habitats, and damage from projectiles is usually light. Perhaps for this reason the role of projectiles in intertidal ecology has received little attention. Boulder-fi eld intertidal zones are as common as, if not more common than, rock plat- forms. In boulder fi elds, projectiles are abundant, and the evidence of damage due to projectiles is obvious. Here projectiles may be one of the most important defi ning physical forces in the habitat. SEE ALSO THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Geology, Coastal / Habitat Alteration / Hydrodynamic Forces / Wave Exposure FURTHER READING Carstens. T. 1968. Wave forces on boundaries and submerged bodies. Sarsia FIGURE 6 The intertidal zone on the north side of Cape Blanco, 34: 37–60. Oregon. The large, smooth boulders are made of serpentine, while Dayton, P. K. 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organi- the surrounding rock from which the intertidal platform is formed zation: the provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky is sandstone. The smooth boulders are from a source outside the intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 45: 137–159. intertidal zone and were carried into the intertidal zone by waves. Levin, S. A., and R. -

Baja California Sur, Mexico)

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Geomorphology of a Holocene Hurricane Deposit Eroded from Rhyolite Sea Cliffs on Ensenada Almeja (Baja California Sur, Mexico) Markes E. Johnson 1,* , Rigoberto Guardado-France 2, Erlend M. Johnson 3 and Jorge Ledesma-Vázquez 2 1 Geosciences Department, Williams College, Williamstown, MA 01267, USA 2 Facultad de Ciencias Marinas, Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada 22800, Baja California, Mexico; [email protected] (R.G.-F.); [email protected] (J.L.-V.) 3 Anthropology Department, Tulane University, New Orleans, LA 70018, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-413-597-2329 Received: 22 May 2019; Accepted: 20 June 2019; Published: 22 June 2019 Abstract: This work advances research on the role of hurricanes in degrading the rocky coastline within Mexico’s Gulf of California, most commonly formed by widespread igneous rocks. Under evaluation is a distinct coastal boulder bed (CBB) derived from banded rhyolite with boulders arrayed in a partial-ring configuration against one side of the headland on Ensenada Almeja (Clam Bay) north of Loreto. Preconditions related to the thickness of rhyolite flows and vertical fissures that intersect the flows at right angles along with the specific gravity of banded rhyolite delimit the size, shape and weight of boulders in the Almeja CBB. Mathematical formulae are applied to calculate the wave height generated by storm surge impacting the headland. The average weight of the 25 largest boulders from a transect nearest the bedrock source amounts to 1200 kg but only 30% of the sample is estimated to exceed a full metric ton in weight. -

Marine Biological Investigations in the Bahamas 23. Description of the Littoral Zonation at Nine Bahamian Rocky-Shore Localities

Marine biological investigations in the Bahamas 23. Description of the littoral zonation at nine Bahamian rocky-shore localities Hans Brattström Brattström H. 1999. Description of the littoral zonation at nine Bahamian rocky-shore localities. SARSIA Sarsia 84:319-365. Nine typical, more or less vertical, rocky-shore localities were visited in April-May 1967, and one of these was revisited in March 1968. The topographies of the stations are described and illustrated, and the vertical zonation of their flora and fauna is documented. On the whole the flora and fauna at the stations investigated was fairly poor. At least 37 species of algae and 85 animal species were recorded, but only 15 algae and 71 animals could be identified to species. Most of the algae were too undeveloped or grazed down to permit a reliable identification. Only half as many species were found at these nine stations as were found on three almost horizontal beach-rock stations described in an earlier article. Whereas many of the latter lived in a system of cavities below the rocks, all species found on the nine vertical stations were exposed to waves and the hot midday sun. The common yellow, black, grey, and white zones typical of the Bahamas, were often well-devel- oped. Some algae and many of the animals formed distinct belts within these zones, the higher up the more exposed the rocks were. Though tides and exposure presumably are responsible for the general zonation pattern, it is likely that in the cirripeds and vermetids the way of food-intake determines their upper limit. -

Rocky Intertidal Sensitivity

Rocky Intertidal1 Executive Summary The rocky intertidal habitat consists of Rocky Intertidal Score Confidence rocky substrate found between high and low tide water levels. This habitat has a Sensitivity 4 Moderate-High 2 Moderate transcontinental geographic extent, is Exposure 4 Moderate-High 2 Moderate moderately continuous throughout the Adaptive Capacity 4 Moderate-High 2 Moderate study region, and is considered to be in Vulnerability 3 Moderate 2 Moderate relatively pristine condition by workshop participants. Key climate sensitivities identified for this habitat by workshop participants includes air temperature, salinity, wave action, pH, and erosion. Key non-climate sensitivities include armoring, pollution/oil spills, recreation/trampling, and invasive species/species range expansions. Rocky intertidal habitat is widespread, continuous, and a dominant feature of the study region, composing 39% of the shoreline. This system generally displays high recovery potential, in part due to species’ short lifespans and high fecundity, as well as high species diversity, due to the diversity in substrate type. Community dynamics are dependent on the abundance, distribution, and interactions of the California mussel (Mytilus californianus) and the ochre sea star (Pisaster ochraceus). Management potential is considered low due to the inability to prevent climate impacts from affecting the habitat. However, societal value for this habitat is considered high due to its importance in research, recreation, and harvest. Sensitivity I. Sensitivities -

By the Sea a Guide to the Coastal Zone of Atlantic

BY THE SEA A GUIDE TO THE COASTAL ZONE OF ATLANTIC CANADA USER’S GUIDE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS: FUNDING: Department of Fisheries and Oceans, COORDINATORS: Roland D. Chiasson, Sabine B. Dietz SUPERVISION & REVISIONS: John A. Legault, Sophie Bastien-Daigle GRAPHICS: Sabine Dietz, Ursula Koch, Elke Leitner, Jean-Raymond Gallien (used with permission from the N.B. Department of Natural Resources and Energy) Également disponible en français. Fisheries Pêches Piper Project/Projet siffleur and Oceans et Océans 4800 Route 11 Tabusintac, N.B. E9H 1J6 Department of Fisheries and Oceans Habitat Management Division 343 Archibald Street Moncton, N.B. E1C 9B6 Prepared by: Corvus Consultants Inc., Tabusintac, N.B., Canada Cat. no. S-23-289/1996 E ©1996 ISBN 0-660-16410-8 THE MODULES MODULE 1 : INTRODUCTORY MODULE MODULE 2 : TO THE HORIZON - THE NEARSHORE MODULE 3 : ESTUARIES MODULE 4 : SALT MARSHES MODULE 5 : TIDAL MUDFLATS MODULE 6 : SANDY BEACHES AND DUNES MODULE 7 : ROCKY SHORES MODULE 8 : COASTAL ISLANDS AND CLIFFS MODULE 9 : COBBLE BEACHES MODULE 10 : COASTAL BOGS MODULE 11 : FRESHWATER BARRIER PONDS MODULE 12 : FJORDS MODULE 13 : ACTIVITIES ABOUT THE MANUAL .......................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Who is this guide for? 3 1.2. How is this guide organized? 3 1.3. About the ecosystem modules 3 1.4. How to use the ecosystem modules: 4 MODULE DESCRIPTIONS, LEARNING OBJECTIVES, STUDY QUESTIONS AND SUGGESTED ACTIVITIES..................... 5 Activity Suggestions 6 Matrix -

Lesson One: What Is the Rocky Shore?

Partnerships for Reform through Investigative Science and Mathematics Hawaii’s Rocky What is the Rocky Shoreline? Shore Summary Students will first talk about what they already know about the rocky shore from their collective experiences. They will next talk about Concepts what they want to learn about the rocky shore. Students will then be Students will be introduced to the rocky shore environment through new vocabulary introduced to the rocky and images. shoreline habitat, its physical properties and Objectives an overview of its flora- • Students will discuss what they already know about the rocky fauna. They will inquire shore/line. with one another about • Students will form questions about what they want to know what they know and about the rocky shore. would like to know • Students will be introduced to some organisms that live on the about the unique rocky rocky shore. shore habitat. • Students will learn how the changing tide makes the rocky shore a habitat that is always in flux. HCPS III Benchmarks SC.1.2.2 SC.1.6.1 Materials Bucket Duration Copied free-association words and cut into strips 45 minutes Large photos of rocky shores and tide pools to show to the class (laminated if possible) Source Material MARE Rocky Making Connections Seashores Students have probably seen the rocky shore and explored its www.coast-nopp.org tidepools during trips to the beach in Hawai‘i. They will discuss this PRISM familiar environment through new vocabulary and physical science. Vocabulary Teacher Prep for Activity Desiccation Prepare a “Rocky Shores Vocabulary List” on chart paper. -

Rocky Shores of the Gold Coast

Rocky shores of the Gold Coast Rocky shores are an attractive feature of our city’s coastline (see Figure 1). Figure 1. The rocky shore at Burleigh Heads (Source: GCCM) The Gold Coast has long been renowned for its vast stretches of sandy beaches. A lesser-known environment is the rocky shore, which ‘punctuates the long sweeps of sandy beaches’ that dominate this environment1. The various locations of these rocky outcrops are shown in Figure 2. Each rocky shore has its own distinct ecological composition. This is heavily dependent on aspect and exposure to wave energy. Figure 2. Map showing the distribution of rocky shores on the Gold Coast. Between a rock and a hard place The rocky shore is a tough environment to live in. Here, animals in the intertidal zone are exposed to high energy waves that surge over the surface. On the other hand, those left high and dry can be exposed to scorching temperatures and vulnerable to predation from seabirds. Rocky shores are highly variable environments. On a daily basis, the shore experiences both submersion Figures 3 and 4. The contrasting high and low tide environments at (high tide) and exposure (low tide) (see Figures 3 and Burleigh Heads. (Source: GCCC) 4, respectively). In the longer term, sand supply along Spotted: Wildlife of Gold Coast’s rocky our coastline is in natural flux. Wave action moves sand along the coast, sometimes covering rocky outcrops. shores The flora and fauna of this ecosystem have adapted to Wildlife on the rocky shore have adapted to these 2 deal with this dynamic environment. -

Acadian-North Atlantic Rocky Coast

Acadian-North Atlantic Rocky Coast Macrogroup: Rocky Coast yourStateNatural Heritage Ecologist for more information about this habitat. This is modeledmap a distributiononbased current and is data nota substitute for field inventory. based Contact © Josh Royte (The Nature Conservancy, Maine) Description: An open rocky shoreline found in the narrow zone between the high tide line and the upland wooded areas. These intertidal zones of solid rock are often covered with seaweeds that tolerate extremes of exposure to winds, waves, currents, and ice-scour. Blue-green algae are common in the high intertidal zones; barnacles in the mid- intertidal zone; mussels in the lower intertidal. Diagnostic species include seaweeds (Irish moss, rockweed, knotted wrack, hollow-stemmed kelp) and invertebrates (blue mussels, common periwinkles, dogwhelks, and springtails). Tide pools provide nurseries for lumpfish, sea snails, pollock, and other fish. Many bird species frequent these: State Distribution: CT, MA, ME, NH, NY, RI purple sandpiper, ruddy turnstone, sanderling, black-bellied plover, American oystercatcher, and pectoral sandpiper. Total Habitat Acreage: 7,706 Ecological Setting and Natural Processes: Percent Conserved: 16.6% This system is found on rocky shores from the New England State State GAP 1&2 GAP 3 Unsecured coast to the Canadian Maritimes. Slopes vary from flat rocks State Habitat % Acreage (acres) (acres) (acres) to cliffs. The intertidal zone widens with increasing maritime ME 41% 3,146 270 223 2,653 influence, and subjects these landscapes to extremes of MA 34% 2,626 150 305 2,171 wind, salt spray, and fog. Many coastal islands in this zone have graminoid-shrub areas that were maintained by sheep RI 14% 1,064 97 61 907 grazing and that now persist even after grazing has ceased. -

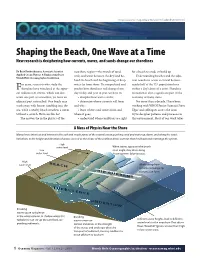

Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New Research Is Deciphering How Currents, Waves, and Sands Change Our Shorelines

http://oceanusmag.whoi.edu/v43n1/raubenheimer.html Shaping the Beach, One Wave at a Time New research is deciphering how currents, waves, and sands change our shorelines By Britt Raubenheimer, Associate Scientist nearshore region—the stretch of sand, for a beach to erode or build up. Applied Ocean Physics & Engineering Dept. rock, and water between the dry land be- Understanding beaches and the adja- Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution hind the beach and the beginning of deep cent nearshore ocean is critical because or years, scientists who study the water far from shore. To comprehend and nearly half of the U.S. population lives Fshoreline have wondered at the appar- predict how shorelines will change from within a day’s drive of a coast. Shoreline ent fickleness of storms, which can dev- day to day and year to year, we have to: recreation is also a significant part of the astate one part of a coastline, yet leave an • decipher how waves evolve; economy of many states. adjacent part untouched. One beach may • determine where currents will form For more than a decade, I have been wash away, with houses tumbling into the and why; working with WHOI Senior Scientist Steve sea, while a nearby beach weathers a storm • learn where sand comes from and Elgar and colleagues across the coun- without a scratch. How can this be? where it goes; try to decipher patterns and processes in The answers lie in the physics of the • understand when conditions are right this environment. Most of our work takes A Mess of Physics Near the Shore Many forces intersect and interact in the surf and swash zones of the coastal ocean, pushing sand and water up, down, and along the coast. -

Coastal Processes Note for Beach Protection Works at Dunbar East Beach Version 2

Note / Memo HaskoningDHV UK Ltd. Industry & Buildings To: Marine Scotland From: Morwenna See Date: 15 April 2019 Copy: Our reference: PB8131-RHD-ZZ-XX-NT-Z-0002 Classification: Project related Subject: Coastal processes note for beach protection works at Dunbar East Beach Version 2 1 Introduction This note outlines the potential environmental impacts of a proposed seawall defence project at Dunbar East Beach to support an EIA screening and marine licence application to Marine Scotland. East Lothian Council is proposing construction of a seawall defence project to promote the natural regeneration of Dunbar East Beach. The works are to repair/replace an existing groyne at the south of the site that has fallen into disrepair alongside works to improve the exposure conditions in the bay to encourage any sediment that is in the local system to remain on foreshore. It is hoped by reducing the wave conditions at the beach combined with the refurbished groyne that the bay will retain more sediment and in the long term regain the amenity value that has been lost in recent years. Dunbar East Beach was a sandy beach as recently as 2013, however, following successive storms in 2014 the beach was almost entirely eroded and further storms in the subsequent years has left the frontage devoid of any sediment able to form a beach. Works to enhance the retention of sediment on the foreshore have been proposed. A previous project with this aim, placing rock armour around an existing Scottish Water sewer outfall pipe, was undertaken in 2017. However, no change in sediment retention was identified.