Bawley Point in the 1920S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agenda of Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group

Meeting Agenda Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group Meeting Date: Monday, 10 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Please note: Council’s Code of Meeting Practice permits the electronic recording and broadcast of the proceedings of meetings of the Council which are open to the public. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Shoalhaven Tourism Advisory Group - 24 March 2021 ............................................. 1 3. Presentations TA21.11 Rockclimbing - Rob Crow (Owner) - Climb Nowra A space in the agenda for Rob Crow to present on Climbing in the region as requested by STAG. 4. Reports TA21.12 Tourism Manager Update ............................................................................ 3 TA21.13 Election of Office Bearers............................................................................ 6 TA21.14 Visitor Services Update ............................................................................. 13 TA21.15 Destination Marketing ............................................................................... 17 TA21.16 Chair's Report ........................................................................................... 48 TA21.17 River Festival Update ................................................................................ 50 TA21.18 Event and Investment Report ................................................................... -

W I T H S U P P L E M E N T . Thnrsdfty, Notemtwr 11, 1880

si mm ohell, wh<>i;atarted. for their iiortbern I. I. Fuller. Little Seal's Oolamn. home tbliiwieek. Several of the graiiK- ers of this place unitied the Dansvllle lodge on tnolr supper night, Friday, WITH SUPPLEMENT. Oct. 21). Mr. and Mrs. Menzo Gonklhi will move north in a: short thne. Mr. IHIllllRrMDH GOODS! C. owcsa farmiu Isabella county, YOU CAN SAVE MONEY Thnrsdfty, NoTemtwr 11, 1880. Tho familiar hoot of the ix)lUiclan is hushed for a while, while that of tbo BY BTJYINO TOUB THE COUNTY. large eyed bird still breaks tbe stillness of night, as he sits on his snow clad porch, and calls whoo-hoo hoo'o*? "Oar- KINNIEYILLE. lleld nnd Aithur" echo answers. Clothing, Hats, Caps, and Pleasant over head, but whnt a mess Asft Waterhouse talks of moving to Webbervllle, where cash is plenty nnd under foot. Just stop at the Palace store and work Is Ig good demand. Gents' Furnishing Goods, Snow fell to tuo depth of aboutelght- VOL. XXn.~NO. 47. eeu Inches last Friday und Saturday, MASON, MIcirmURSDAY. JSTOVeSeR 18, 18807 and we listened to the jingle of tho WASHINGTON. Look at those rare bargains hells on Sunday. WHOLE NO. 1141. Scntiinontii nnrt Feelliiga In nnarnril to Miison Ilii.siiie.ss Directory At the donation given for tho benefit the RIeellon nt the Watlvnnl C'npltni space iu our columns to send us tbciv promised, hut will have to come later of Bov. S. Nelson last Thursday even For you, your friend and neighbor cojiy cnrl.y. niul recommend thnt same bo ndopted. -

Agenda of Strategy and Assets Committee

Meeting Agenda Strategy and Assets Committee Meeting Date: Tuesday, 18 May, 2021 Location: Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra Time: 5.00pm Membership (Quorum - 5) Clr John Wells - Chairperson Clr Bob Proudfoot All Councillors Chief Executive Officer or nominee Please note: The proceedings of this meeting (including presentations, deputations and debate) will be webcast and may be recorded and broadcast under the provisions of the Code of Meeting Practice. Your attendance at this meeting is taken as consent to the possibility that your image and/or voice may be recorded and broadcast to the public. Agenda 1. Apologies / Leave of Absence 2. Confirmation of Minutes • Strategy and Assets Committee - 13 April 2021 ........................................................ 1 3. Declarations of Interest 4. Mayoral Minute 5. Deputations and Presentations 6. Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice Notices of Motion / Questions on Notice SA21.73 Notice of Motion - Creating a Dementia Friendly Shoalhaven ................... 23 SA21.74 Notice of Motion - Reconstruction and Sealing Hames Rd Parma ............. 25 SA21.75 Notice of Motion - Cost of Refurbishment of the Mayoral Office ................ 26 SA21.76 Notice of Motion - Madeira Vine Infestation Transport For NSW Land Berry ......................................................................................................... 27 SA21.77 Notice of Motion - Possible RAAF World War 2 Memorial ......................... 28 7. Reports CEO SA21.78 Application for Community -

Discovering Bawley Point

Discovering Bawley Point A paradise on the NSW south coast 2 The Bawley Coast Contents Introduction page 3 Our history page 4 Wildlife page 6 Activities pages 8 Shopping page 14 Cafes and restaurants page 15 Vineyards and berry farms page 16 This e-book was written and published by Bill Powell, Bawley Bush Cottages, February 2011. Web: bawleybushcottages.com.au Email: [email protected] 101 Willinga Rd, Bawley Point, NSW 2539, Australia Tel: (61) 2 4457 1580 Bookings: (61) 2 4480 6754 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- sa/3.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Fran- cisco, California, 94105, USA. 3 Introduction A holiday on the Bawley Coast is still just like it was for our grandparents in their youth. Simple, sunny, lazy, memorable. Regenerating. This publication gives an over- view of the Bawley Coast area, its history and its present. There is also information about our coastal retreat, Bawley Bush Cottages. We hope this guide improves your ex- perience of this beautiful piece of Australian coast and hinterland. Here on the Bawley Coast geological history, evidence of aboriginal occupation and the more recent settler past are as easily visible as our beaches, lakes and cafes. Our coast remains relatively unspoiled by many of the trappings of town life. Recreation, sustain- ability and environmental protection are our high priorities. Landcare, dunecare and the protection of endangered species are examples of environ- mental activities important to our community. -

Special Development Committee 17 July 2013

SHOALHAVEN CITY COUNCIL SPECIAL DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE To be held on Wednesday, 17 July, 2013 Commencing at 4.00 pm. 11 July, 2013 Councillors, NOTICE OF MEETING You are hereby requested to attend a meeting of the Development Committee of the Council of the City of Shoalhaven, to be held in Council Chambers, City Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra on Wednesday, 17 July, 2013 commencing at 4.00 pm for consideration of the following business. R D Pigg General Manager Membership (Quorum – 5) Clr White – Chairperson All Councillors General Manager or nominee (Assistant General Manager) BUSINESS OF MEETING 1. Apologies 2. Declarations of Interest 3. Deputations 4. Report of the General Manager Planning and Development – Draft Shoalhaven LEP 2013 – Consideration of Submissions – Post re-exhibition 5. Addendum Reports Note: The attention of Councillors is drawn to the resolution MIN08.907 which states: a) That in any circumstances where a DA is called-in by Council for determination, then as a matter of policy, Council include its reasons for doing so in the resolution. b) That Council adopt as policy, that Councillor voting in Development Committee meeting be recorded in the minutes. c) That Council adopt as policy that it will record the reasons for decisions involving applications for significant variations to Council policies, DCP’s or other development standards, whether the decision is either approval of the variation or refusal. Note: The attention of Councillors is drawn to Section 451 of the Local Government Act and Regulations and Code of Conduct regarding the requirements to declare pecuniary and non- pecuniary Interest in matters before Council. -

Narrative of an Expedition Into Central Australia Performed Under the Authority of Her Majesty's Government During the Years 1844, 5, and 6

Narrative of an Expedition into Central Australia Performed under the Authority of Her Majesty's Government during the Years 1844, 5, and 6 Together with a Notice of the Province of South Australia in 1847 Sturt, Charles (1795-1869) A digital text sponsored by William and Sarah Nelson University of Sydney Library Sydney 2001 http://setis.library.usyd.edu.au/ozlit/ © University of Sydney Library. The texts and Images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Source Text: Prepared from the print edition published by T. and W. Boone, 29, New Bond Street. London 1849 All quotation marks retained as data All unambiguous end-of-line hyphens have been removed, and the trailing part of a word has been joined to the preceding line. First Published: 1849 Languages: F5202 Australian Etexts 1840-1869 exploration and explorers (land) prose nonfiction 2001 Creagh Cole Coordinator Final Checking and Parsing Narrative of an Expedition into Central Australia Performed under the Authority of Her Majesty's Government during the Years 1844, 5, and 6. Together with a Notice of the Province of South Australia in 1847 By F.L.S. F.R.G.S. etc. etc. Author of “Two Expeditions Into Southern Australia” London T. and W. Boone, 29, New Bond Street. 1849 To The Right Honorable The Earl Grey, ETC. ETC. ETC. MY LORD, ALTHOUGH the services recorded in the following pages, which your Lordship permits me to dedicate to you, have not resulted in the discovery of any country immediately available for the purposes of colonization, I would yet venture to hope that they have not been fruitlessly undertaken, but that, as on the occasion of my voyage down the Murray River, they will be the precursors of future advantage to my country and to the Australian colonies. -

Maud Matters

Wherry Maud Trust August 2018 Maud Matters Newsletter No.6 Your trustees are happy with Wherry Maud Trust's progress and glad that this year we have even more members who take an active part in sailing on Maud, maintaining her and showing her off to the wider public. We should all celebrate the fact that this year there are eight wherry- rigged vessels afloat. Each plays an important role in the Broadland wherry scene and your membership and support enables Maud to play her part. INSIDE THIS ISSUE Grants Awarded ...................... 2 MESSAGE FROM OUR PATRON Maud at Heritage Open Days .. 3 RICHARD JEWSON JP—LORD LIEUTENANT OF NORFOLK HAS WRITTEN AS FOLLOWS: Maud’s Winter Maintenance... 3 Maud’s Trips + Other Events .. 4 “It has been interesting for me this year to see how Wherry Maud Trust is Upcoming WMT Events .......... 7 growing and using new ways to bring "our" wherry to the attention of the Associate membership ............ 7 public and of course to generate Meet the Skippers ................... 8 funds for her upkeep. Crew Matters ........................... 8 In May I was pleased to attend the Other Historic Vessels ............ 9 Wherry Maud Trust art exhibition at Volunteering ........................... 12 Ranworth. It showcased the work of Social Media ............................ 13 local artists and was the Trust's first Other Events Upcoming.......... 13 large-scale funding event . The suc- Contact Us ............................... 14 cess of the event was due to the many volunteers who helped over the two days. Volunteers were serving light refreshments, meeting and greeting the public and explaining the purpose of the event and the im- portance of Maud in the Broads scene. -

Dunn & Lewis Youth Development Foundation Community Directory

'This project was funded by Dunn & Lewis Youth Development Foundation The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing' Community Directory Every effort has been made to ensure that the information displayed is correct at the time of publishing. The Dunn & Lewis Foundation takes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. INSIDE There is an information form on the previous page for organizations that would like to be included in future editions of the directory. ALL AGES phone: 4455 2895 email: [email protected] PRE-SCHOOLERS 1 www.dunnlewisfoundation.org.au CHILDREN 3 Thank you to all who contributed to this project CHILDCARE 4 and participated in our programs. CHILDCARE CENTRES 5 David Curtis, Dwayne Dickson, Kyle Eacott, Jordan Flood, YOUTH / JUNIORS 6 Jim Gambell, Jamie Macallef, Ray Maling, Jacqueline Mulligan, SENIORS 8 Rick Pedder, Tanya Prisk, Alisha Stoneham, Phillip Stoneham, Te-neale Brown, Samantha Claasen, Simon Deutscher, TUITION 10 Sarah Free, Karlee Dunn, Chloe Riddell, Codie Riddell, Denise Riddell, MARTIAL ARTS 11 Jane Dowling, Gayle Dunn, Patricia White, Cheryl Hobson The Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing FITNESS 13 TAFE Illawarra BALL SPORTS 14 ACTIVITIES 16 ARTS & CRAFTS 18 INVITATION TO BE A SPONSOR HOBBIES 20 Special Christmas Edition PERFORMING ARTS 22 Here is a great opportunity for your organization to support the Dunn & Lewis WATER SPORTS 24 Youth Development Foundation‘s Community Directory Project through SUPPORT GROUPS 26 business and corporate sponsorship. You can start your sponsorship with the holiday season edition. Over 10,000 copies will go into to every home, EMERGENCY SERVICES 28 information and tourist centre in our district. -

Asset Management Plan Bus Shelters

Asset Management Plan Bus Shelters Policy Number: POL07/75 Adopted: 29 April 2003 Minute Number: MIN03.468 File: 25442 Produced By: Strategic Planning Group Review Date: 29/04/2004 For more information contact the Strategic Planning Group Administrative Centre, Bridge Road, Nowra • Telephone (02) 4429 3111 • Fax (02) 4422 1816 • PO Box 42 Nowra 2541 Southern District Office – Deering Street, Ulladulla • Telephone (02) 4429 8999 • Fax (02) 4429 8939 • PO Box 737 Ulladulla [email protected] • www.shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au CONTENTS 1. PROGRAM OBJECTIVES ...........................................................................................................1 2. ASSET DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................................1 3. ASSET EXTENT AND CONDITION ..........................................................................................1 4. CAPITAL WORKS STRATEGIES..............................................................................................2 4.1. Provision of New Shelters.....................................................................................................2 4.2. Replacement Strategy ...........................................................................................................2 4.3. Enhancement Strategies ........................................................................................................3 5. FUNDING NEED SUMMARY AND LEVELS OF SERVICE..................................................3 5.1. Summary -

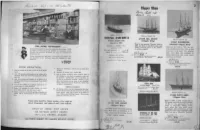

Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~

2 Clipper Ships ~4A1'11l ~ C(Ji? ~·4 ~/. MODEL SHIPWAYS Marine Model Co. YOUNG AMERICA #1079 SEA WITCH Marine Model Co. Extreme Clipper Ship (Clipper Ship) New York, 1853 #1 084 SWORDFISH First of the famous Clippers, built in (Medium Clipper Ship) LENGTH 21"-HEIGHT 13\4" 1846, she had an exciting career and OUR MODEL DEPARTMENT • • • Designed and built in 1851, her rec SCALE f."= I Ft. holds a unique place in the history Stocked from keel to topmast with ship model kits. Hulls of sailing vessels. ord passage from New York to San of finest carved wood, of plastic, of moulded wood. Plans and instructions -··········-·············· $ 1.00 Francisco in 91 days was eclipsed Scale 1/8" = I ft. Models for youthful builders as well as experienced mplete kit --·----- $10o25 only once. She also engaged in professionals. Length & height 36" x 24 " Mahogany hull optional. Plan only, $4.QO China Sea trade and made many Price complete as illustrated with mahogany Come a:r:1d see us if you can - or send your orders and passages to Canton. be assured of our genuine personal interest in your Add $1.00 to above price. hull and baseboard . Brass pedestals . $49,95 selection. Scale 3/32" = I ft. Hull only, on 3"t" scale, $11.50 Length & height 23" x 15" ~LISS Plan only, $1.50 & CO., INC. Price complete as illustrated with mahogany hull and baseboard. Brass pedestals. POSTAL INSTRUCTIONS $27.95 7. Returns for exchange or refund must be made within 1. Add :Jrt postage to all orders under $1 .00 for Boston 10 days. -

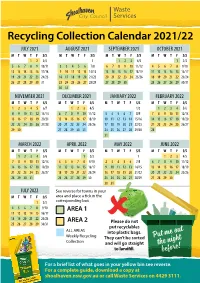

For a Brief List of What Goes in Your Yellow Bin See Reverse. for a Complete Guide, Download a Copy at Shoalhaven.Nsw.Gov.Au Or Call Waste Services on 4429 3111

For a brief list of what goes in your yellow bin see reverse. For a complete guide, download a copy at shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au or call Waste Services on 4429 3111. Calendar pick-up dates are colour coded to correspond with your area. AREA 1 Hyams Beach AREA 2 Mollymook Basin View Illaroo Back Forest Morton Bawley Point Jaspers Brush Bamarang Mundamia Beaumont Kings Point Bangalee Narrawallee Bellawongarah Kioloa Barrengarry North Nowra Berry Lake Tabourie Bendalong Nowra Bewong Meroo Meadow* Berrara Nowra Hill* Bomaderry Milton* Berringer Lake Numbaa Broughton Mollymook Beach* Bolong Pointer Mountain Budgong Myola Brundee* Pyree* Bundewallah Old Erowal Bay Cambewarra Sanctuary Point Burrill Lake Orient Point Comerong Island Shoalhaven Heads Callala Bay Parma Conjola South Nowra Callala Beach Termeil* Conjola Park St Georges Basin Croobyar* Tomerong* Coolangatta Sussex Inlet Culburra Beach Vincentia Cudmirrah Swanhaven Currarong Wandandian Cunjurong Point Tapitallee* Depot Beach Watersleigh Far Meadow* Terara Dolphin Point Wattamolla Fishermans Paradise Ulladulla Durras North Woodhill Jerrawangala West Nowra East Lynne Woollamia Kangaroo Valley Wollumboola Erowal Bay Worrigee* Lake Conjola Woodburn Falls Creek Worrowing Heights Little Forest Woodstock Greenwell Point Wrights Beach Longreach Yatte Yattah Huskisson Yerriyong Manyana * Please note: A small number of properties in these towns have their recycling collected on the alternate week indicated on this calendar schedule. Please go to shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au/my-area and search your address or call Waste Services on 4429 3111. What goes in your yellow bin Get the Guide! • Glass Bottles and Jars Download a copy at • Paper and Flattened Cardboard shoalhaven.nsw.gov.au • Milk and Juice Containers or call Waste Services • Rigid Plastic Containers (eg detergent, sauce, on 4429 3111. -

Bendalong to Bawley

FREE Bendalong to Bawley COMMUNITY DIRECTORY Your FREE guide to active living Holiday Style 2009/10 Dunn & Lewis Youth Development Foundation Mobile phones Accessories Broadband Home phones Installations Networking Connect to a new mobile phone plan Dec/Jan and receive a free mobile car charger Call in to see our friendly staff: Jo, Garry & Patricia Shows Desktop (3).lnk Dunn & Lewis Youth Development Foundation LIVE YOUR BEST LIFE COMMUNITY DIRECTORY special holiday edition ... The Directory is a source of information about healthy active living and personal wellbeing; the ‘how, what, when, and where ...’ in a practical, informative magazine. Find new activities and access the best facilities in our district for the best holiday time ever... As part of ongoing development a ‘hub’ of support will be available at the Dunn & Lewis Youth Foundation Website. It will be a centre of interactive tools designed to make access to organised activities and participation easy and effective. Stay tuned ... Directory available as a PDF at www.dunnlewisfoundation.org.au ACTIVITIES 2 CHURCH SERVICES 6 EVENTS 7 MARKETS 8 PARKS and RESERVES 9 VACATION CARE 9 BEACHES and POOLS 11 COMMUNITY SERVICES 12 BOAT RAMPS 13 EMERGENCY and LOCAL SERVICES 13 More information about regular programs and events, is in the Summer issue of Live Your Best Life. Copies available at Dunn & Lewis Youth Development Foundation 141 St Vincent St Ulladulla 4455 4626 or 4455 2895 available on-line as a PDF www.dunnlewisfoundation.org.au Dunn & Lewis Youth Development Foundation ACTIVITIES Every Saturday during School Holidays Guided history walking tours of Milton will be held every Saturday including Boxing Day bookings are advised $10.00 per adult, Family: 2 adults and children $25.00 with some great historic Milton postcards to be won.