Oral and Perioral Piercing Complications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Care of Antiques & Works Of

THE BRITISH ANTIQUE DEALERS’ ASSOCIATION The Care of Antiques & Works of Art The Care of Antiques & Works of Art Antiques have been passed down by our ancestors over the centuries to our present generation, so by their very nature have stood the test of time. They may have taken a few knocks in those earlier ages, but surprisingly, despite all our 21st-century creature comforts, it is the modern world, with its central heating and chemical cleaning products, which poses particular challenges for such objects. You may have spent a considerable sum acquiring a beautiful and valuable antique, so you do not want to throw away that investment by failing to look after it. Half the battle is knowing just when to try and remedy a defect yourself and when to leave it to the experts. Here are some basic recommendations, compiled through extensive consultation with specialists who have the greatest experience of handling antiques on a daily basis – members of The British Antique Dealers’ Association. We hope this guide helps you to decide what to do, and when. INTERNATIONAL DIVISION As specialist fine art & antique Lloyd’s insurance brokers we are delighted to sponsor this BADA guide. Besso Limited • 8‒11 Crescent • London ec3n 2ly near America Square Telephone +44 ⁽0⁾20 7480 1094 Fax +44 ⁽0⁾20 7480 1277 [email protected] • www.besso.co.uk Published for The British Antique Dealers’ Association by CRAFT PUBLISHING 16–24 Underwood Street • London n1 7jq T: +44⁽0⁾207 1483 483 E: [email protected] www.craftpublishing.com The Association gratefully acknowledges the editorial assistance of Nöel Riley in compiling this guide. -

The Pearl Range FACE BRICKS – ONE NEW TEXTURE, 5 CONTEMPORARY COLOURS January 2020 76

INTRODUCING The Pearl Range FACE BRICKS – ONE NEW TEXTURE, 5 CONTEMPORARY COLOURS January 2020 76 230 110 Bricks per sqm = 48.5 Bricks per pack = 264 The Pearl Range Nominal weight per pack = 792kg With clean contemporary lines and even monochromatic colour, the new Pearl Range will add individuality and flare to your next project. Featuring a distinctive smooth face with a subtle cut finish and available in five modern colours. Grey Pearl The Pearl Range Clay Face Bricks 230x110x76mm Amber Pearl Copper Pearl Copper Pearl Ivory Pearl Grey Pearl Black Pearl For more information about the Pearl Range Call us on 13 15 40 Visit our website at www.midlandbrick.com.au Talk to your Midland Brick Sales Representative Shade variations occur from batch to batch. Colours shown in this brochure are indicative only and should not be used for fi nal selection. Whilst every effort is made to supply product consistent with brochures and examples, some colour and texture variation may occur within production runs. Not all colours are available in every region for each product. See your retailer for colours available in your region. Products ordered should be chosen from actual samples current at the time of order and are subject to availability. Photographs in this brochure are only representative of Midland Brick products and the appearance and effect that may be achieved by their use. Samples and displays should be viewed as a guide only. Brochure colours may vary due to the limitations and variations in the printing process. Customers should ensure all delivered products are acceptable, and any concerns about products are made prior to laying. -

Repoussé Work for Amateurs

rf Bi oN? ^ ^ iTION av op OCT i 3 f943 2 MAY 8 1933 DEC 3 1938 MAY 6 id i 28 dec j o m? Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Public Library http://www.archive.org/details/repoussworkforamOOhasl GROUP OF LEAVES. Repousse Work for Amateurs. : REPOUSSE WORK FOR AMATEURS: BEING THE ART OF ORNAMENTING THIN METAL WITH RAISED FIGURES. tfjLd*- 6 By L. L. HASLOPE. ILLUSTRATED. LONDON L. UPCOTT GILL, 170, STRAND, W.C, 1887. PRINTED BY A. BRADLEY, 170, STRAND, LONDON. 3W PREFACE. " JjJjtfN these days, when of making books there is no end," ^*^ and every description of work, whether professional or amateur, has a literature of its own, it is strange that scarcely anything should have been written on the fascinating arts of Chasing and Repousse Work. It is true that a few articles have appeared in various periodicals on the subject, but with scarcely an exception they treated only of Working on Wood, and the directions given were generally crude and imperfect. This is the more surprising when we consider how fashionable Repousse Work has become of late years, both here and in America; indeed, in the latter country, "Do you pound brass ? " is said to be a very common question. I have written the following pages in the hope that they might, in some measure, supply a want, and prove of service to my brother amateurs. It has been hinted to me that some of my chapters are rather "advanced;" in other words, that I have gone farther than amateurs are likely to follow me. -

2014 State of Ivory Demand in China

2012–2014 ABOUT WILDAID WildAid’s mission is to end the illegal wildlife trade in our lifetimes by reducing demand through public awareness campaigns and providing comprehensive marine protection. The illegal wildlife trade is estimated to be worth over $10 billion (USD) per year and has drastically reduced many wildlife populations around the world. Just like the drug trade, law and enforcement efforts have not been able to resolve the problem. Every year, hundreds of millions of dollars are spent protecting animals in the wild, yet virtually nothing is spent on stemming the demand for wildlife parts and products. WildAid is the only organization focused on reducing the demand for these products, with the strong and simple message: when the buying stops, the killing can too. Via public service announcements and short form documentary pieces, WildAid partners with Save the Elephants, African Wildlife Foundation, Virgin Unite, and The Yao Ming Foundation to educate consumers and reduce the demand for ivory products worldwide. Through our highly leveraged pro-bono media distribution outlets, our message reaches hundreds of millions of people each year in China alone. www.wildaid.org CONTACT INFORMATION WILDAID 744 Montgomery St #300 San Francisco, CA 94111 Tel: 415.834.3174 Christina Vallianos [email protected] Special thanks to the following supporters & partners PARTNERS who have made this work possible: Beijing Horizonkey Information & Consulting Co., Ltd. Save the Elephants African Wildlife Foundation Virgin Unite Yao Ming Foundation -

Bone, Antler, Ivory and Teeth (PDF)

Bone, Antler, Ivory, and Teeth Found in such items as tools, jewelry, and decorations Identification and General Information Items derived from skeletal materials are both versatile and durable. Bone, antler, ivory, and teeth have been used for various tools and for ornamentation. Because ivory is easily carved yet durable, it has also long been used by many cultures as a medium for recorded information. Bones and teeth from many different animals, including mammals, birds, and fish, may be found in items in all shapes and sizes. Each culture uses the indigenous animals in its region. Identifying bones and teeth used in an item can be easy or difficult, depending on how they were processed and used. Frequently, bones and teeth were minimally processed, and the surfaces are still visible, allowing identification by color (off-white to pale yellow), shape, and composition. Bird, fish, and reptile bones are usually lighter in mass and color than mammal bones. Bone and antler can be used in their natural form, or polished with sand and other abrasives to a very smooth and glossy surface. Bone is sometimes confused with ivory, which is also yellowish and compact. Sea mammal ivory, which is the prevalent source used by American Indians, is distinct in structure. Walrus ivory, the most common sea mammal ivory, has a dense outer layer and a mottled inner core. Bone and antler in archaeological collections are often burnt and can be blue black to whitish gray. Charred bone or antler can be mistaken for wood. Magnification helps to distinguish bone from similar materials, as it has a thin solid layer surrounding a porous interior structure with a hollow core where the marrow is contained. -

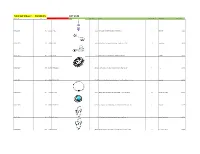

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 Location Id Lot # Item Id Sku Image Store Price Model Store Quantity Classification Total Value

Total Lot Value = $5,520.15 LOT #149 location_id Lot # item_id sku Image store_price model store_quantity classification Total Value A10-S11-D009 149 143692 BR-2072 $11.99 Pink CZ Sparkling Heart Dangle Belly Button Ring 1 Belly Ring $11.99 A10-S11-D010 149 67496 BB-1011 $4.95 Abstract Palm Tree Surgical Steel Tongue Ring Barbell - 14G 10 Tongue Ring $49.50 A10-S11-D013 149 113117 CA-1346 $11.95 Triple Bezel CZ 925 Sterling Silver Cartilage Earring Stud 6 Cartilage $71.70 A10-S11-D017 149 150789 IX-FR1313-10 $17.95 Black-Plated Stainless Steel Interlocked Pattern Ring - Size 10 1 Ring $17.95 A10-S11-D022 149 168496 FT9-PSA15-25 $21.95 Tree of Life Gold Tone Surgical Steel Double Flare Tunnel Plugs - 1" - Pair 2 Plugs Sale $43.90 A10-S11-D024 149 67502 CBR-1004 $10.95 Hollow Heart .925 Sterling Silver Captive Bead Ring - 16 Gauge CBR 10 Captive Ring , Daith $109.50 A10-S11-D031 149 180005 FT9-PSJ01-05 $11.95 Faux Turquoise Tribal Shield Surgical Steel Double Flare Plugs 4G - Pair 1 Plugs Sale $11.95 A10-S11-D032 149 67518 CBR-1020 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Star Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 4 Captive Ring , Daith $43.80 A10-S11-D034 149 67520 CBR-1022 $10.95 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Butterfly Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $21.90 A10-S11-D035 149 67521 CBR-1023 $8.99 .925 Sterling Silver Hollow Cross Vertical Captive Bead Ring - 16G 2 Captive Ring , Daith $17.98 A10-S11-D036 149 67522 NP-1001 $15.95 Triple CZ .925 Sterling Silver Nipple Piercing Barbell Shield 8 Nipple Ring $127.60 A10-S11-D038 149 -

Patients with Oral/Facial Piercings

PATIENTS WITH ORAL/FACIAL PIERCINGS 2 Credits by Wendy Paquette, LPN, BS Erika Vanterainen, EFDA, LPN Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. P.O. Box 21517 St. Petersburg, FL 33742-1517 Phone 1-877-547-8933 Fax 1-727-546-3500 www.homestudysolutions.com November 2015 to December 2022 Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. is an ADA CERP recognized provider. 2/27/2000 to 5/31/2023 California CERP #3759 Florida CEBP #122 A National Continuing Education Provider Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. 1 Revised 2019 Copyrighted 1999 Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. Expiration date is 3 years from the original release date or last review date, whichever is most recent. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by an information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. If you have any questions or comments about this course, please e-mail [email protected] and put the name of the course on the subject line of the e-mail. We appreciate all feedback. Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. P.O. Box 21517 St. Petersburg, FL 33742-1517 Phone 1-877-547-8933 Fax 1-727-546-3500 www.homestudysolutions.com Printed in the USA Home Study Solutions.com, Inc. 2 PATIENTS WITH ORAL/FACIAL PIERCINGS Course Outline 1. OVERVIEW 2. ANATOMY OF THE TONGUE 3. ANATOMY OF THE LIP 4. THE PIERCING PROCEDURE • Complications and Risks Associated with Oral Jewelry • What role does tongue piercing play with tongue cancer? 5. -

Raymond & Leigh Danielle Austin

PRODUCT TRENDS, BUSINESS TIPS, NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY & INSTAGRAM FAVS Metal Mafia PIERCER SPOTLIGHT: RAYMOND & LEIGH DANIELLE AUSTIN of BODY JEWEL WITH 8 LOCATIONS ACROSS OHIO STATE Friday, August 14th is NATIONAL TONGUE PIERCING DAY! #nationaltonguepiercingday #nationalpiercingholidays #metalmafialove 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Semi Precious Stone Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $7.54 - TBRI14-CD Threadless Starting At $9.80 - TTBR14-CD 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Swarovski Gem Disc Internally Threaded Starting At $5.60 - TBRI14-GD Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-GD @fallenangelokc @holepuncher213 Fallen Angel Tattoo & Body Piercing 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G Titanium Barbell W/ Dome Top 14G ASTM F-67 Titanium Barbell Assortment Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Internally Threaded Starting At $5.46 - TBRI14-DM Starting At $17.55 - ATBRE- Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM Threadless Starting At $8.80 - TTBR14-DM 14G Threaded Barbell W Plain Balls 14G Steel Internally Threaded Barbell W Gem Balls Steel External Starting At $0.28 - SBRE14- 24 Piece Assortment Pack $58.00 - ASBRI145/85 Steel Internal Starting At $1.90 - SBRI14- @the.stabbing.russian Titanium Internal Starting At $5.40 - TBRI14- Read Street Tattoo Parlour ANODIZE ANY ASTM F-136 TITANIUM ITEM IN-HOUSE FOR JUST 30¢ EXTRA PER PIECE! Blue (BL) Bronze (BR) Blurple Dark Blue (DB) Dark Purple (DP) Golden (GO) Light Blue (LB) Light Purple (LP) Pink (PK) Purple (PR) Rosey Gold (RG) Yellow(YW) (Blue-Purple) (BP) 2 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 COPYRIGHT METAL MAFIA 2020 3 CONTENTS Septum Clickers 05 AUGUST METAL MAFIA One trend that's not leaving for sure is the septum piercing. -

(Licensing of Skin Piercing and Tattooing) Order 2006 Local Authority

THE CIVIC GOVERNMENT (SCOTLAND) ACT 1982 (LICENSING OF SKIN PIERCING AND TATTOOING) ORDER 2006 LOCAL AUTHORITY IMPLEMENTATION GUIDE Version 1.8 Scottish Licensing of Skin Piercing and Tattooing Working Group January 2018 Table of Contents PAGE CHAPTER 1 Introduction and Overview of the Order …………………………. 1 CHAPTER 2 Procedures Covered by the Order ……………………………….. 2 CHAPTER 3 Persons Covered by the Order …………………………………… 7 3.1 Persons or Premises – Licensing Requirements ……………………. 7 3.2 Excluded Persons ………………………………………………………. 9 3.2.1 Regulated Healthcare Professionals ………………………………. 9 3.2.2 Charities Offering Services Free-of-Charge ………………………. 10 CHAPTER 4 Requirements of the Order – Premises ………………………… 10 4.1 General State of Repair ……………………………………………….. 10 4.2 Physical Layout of Premises ………………………………………….. 10 4.3 Requirements of Waiting Area ………………………………………… 11 4.4 Requirements of the Treatment Room ………………………………… 12 CHAPTER 5 Requirements of the Order – Operator and Equipment ……… 15 5.1 The Operator ……………………………………………………………. 15 5.1.1 Cleanliness and Clothing ……………………………………………. 16 5.1.2 Conduct ……………………………………………………………….. 17 5.1.3 Training ……………………………………………………………….. 17 5.2 Equipment ……………………………………………………………… 18 5.2.1 Skin Preparation Equipment ……………………………………….. 19 5.2.2 Anaesthetics ………………………………………………………… 20 5.2.3 Needles ……………………………………………………………… 23 5.2.4 Body Piercing Jewellery …………………………………………… 23 5.2.5 Tattoo Inks ………………………………………………………….. 25 5.2.6 General Stock Requirements …………………………………….. 26 CHAPTER 6 Requirements of the Order – Client Information ……………. 27 6.1 Collection of Information on Client …………………………………….. 27 ii Licensing Implementation Guide – Version 1.8 – January 2018 6.1.1 Age …………………………………………………………………… 27 6.1.2 Medical History ……………………………………………………… 28 6.1.3 Consent Forms ……………………………………………………… 28 6.2 Provision of Information to Client ……………………………………… 29 CHAPTER 7 Requirements of the Order – Peripatetic Operators …………. -

2020Stainless Steel and Titanium

2020 stainless steel and titanium What’s behind the Intrinsic Body brand? Our master jewelers expertise and knowledge comes from an exten- sive background in industrial engineering, specifically in the aero- nautical and medical fields where precision is key. This knowl- edge and expertise informs every aspect of the Intrinsic Body brand, from design specifications, fabrication methods and tech- niques to the selection and design of components and equipment used and the best workflow practices implemented to produce each piece. Our philosophy Approaching the design and creation of fine body jewelry like the manufacture of a precision jet engine or medical device makes sense for every element that goes into the work to be of optimum quality. Therefore, only the highest grade materials are used at Intrinsic Body: medical implant grade titanium and stainless steel, fine gold, and semiprecious gemstones. All materials are chosen for their intrinsic beauty and biocompatibility. Every piece of body jew- elry produced at Intrinsic Body is made with the promise that your jewelry will be an intrinsic part of you for many years to come. We Micro - Integration endeavor to create pieces that will stand the test of time in every way. of Technology Quality Beauty Precision in the Human Body 2 Micro - Integration of Technology in the Human Body 3 Implant Grade Titanium Barbells Straight Curved 16g 14g 12g 16g 14g 12g 10g 8g Circular Surface Barbell 16g 14g 12g 14g 2.0, 2.5, or 3.0mm rise height Titanium Labrets and Labret Backs 1 - Piece Labret Back gauge 2 - Piece Labret 18g (1 - pc back + ball) 2.5mm disc gauge 16g - 14g 16g - 14g 4.0mm disc 2 - Piece Labret Back 3 - Piece Labret (disc + post + ball) (disc + post) gauge gauge 16g - 14g 16g - 14g 4 Nose Screws 3/4” length, 20g or 18g 1.5mm Prong Facted 2.0mm 1.5mm Bezel Faceted 2.0mm 1.5mm Plain Ball 1.75mm 2.0mm 8-Gem Flower 4.0mm Clickers Titanium Radiance Clicker Wearing Surface Lengths 20g or 18g 1/4" ID = 3/16" w.s. -

Complications of Oral Piercing

Y T E I C O S L BALKAN JOURNAL OF STOMATOLOGY A ISSN 1107 - 1141 IC G LO TO STOMA Complications of Oral Piercing SUMMARY A. Dermata1, A. Arhakis2 Over the last decade, piercing of the tongue, lip or cheeks has grown 1General Dental Practitioner in popularity, especially among adolescents and young adults. Oral 2Aristotle University of Thessaloniki piercing usually involves the lips, cheeks, tongue or uvula, with the tongue Dental School, Department of Paediatric Dentistry as the most commonly pierced. It is possible for people with jewellery in Thessaloniki, Greece the intraoral and perioral regions to experience problems, such as pain, infection at the site of the piercing, transmission of systemic infections, endocarditis, oedema, airway problems, aspiration of the jewellery, allergy, bleeding, nerve damage, cracking of teeth and restorations, trauma of the gingiva or mucosa, and Ludwig’s angina, as well as changes in speech, mastication and swallowing, or stimulation of salivary flow. With the increased number of patients with pierced intra- and peri-oral sites, dentists should be prepared to address issues, such as potential damage to the teeth and gingiva, and risk of oral infection that could arise as a result of piercing. As general knowledge about this is poor, patients should be educated regarding the dangers that may follow piercing of the oral cavity. LITERATURE REVIEW (LR) Keywords: Oral Piercings; Complications Balk J Stom, 2013; 17:117-121 Introduction are the tongue and lips, but other areas may also be used for piercing, such as the cheek, uvula, and lingual Body piercing is a form of body art or modification, frenum1,7,9. -

Piercing Aftercare

NO KA OI TIKI TATTOO. & BODY PIERCING. PIERCING AFTERCARE 610. South 4TH St. Philadelphia, PA 19147 267.321.0357 www.nokaoitikitattoo.com Aftercare has changed over the years. These days we only suggest saline solution for aftercare or sea salt water soaks. There are several pre mixed medical grade wound care solutions you can buy, such as H2Ocean or Blairex Wound Wash Saline. You should avoid eye care saline,due to the preservatives and additives it contains. You can also make your own solution with non-iodized sea salt (or kosher salt) and distilled water. Take ¼ teaspoon of sea salt and mix it with 8 oz of warm distilled water and you have your saline. You can also mix it in large quantities using ¼ cup of sea salt mixed with 1 gallon of distilled water. You must make sure to use distilled water, as it is the cleanest water you can get. You must also measure the proportions of salt to water. DO NOT GUESS! How to clean your piercing Solutions you should NOT use If using a premixed spray, take a Anti-bacterial liquid soaps: Soaps clean q-tip saturated with the saline like Dial, Lever, and Softsoap are all and gently scrub one side of the based on an ingredient called triclosan. piercing, making sure to remove any Triclosan has been overused to the point discharge from the jewelry and the that many bacteria and germs have edges of the piercing. Repeat the become resistant to it, meaning that process for the other side of the these soaps do not kill as many germs piercing using a fresh q-tip.