Too Early Or Too Late: What Do We Learn from a 30-Year Two-Child Policy Experiment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fenhe (Fen He)

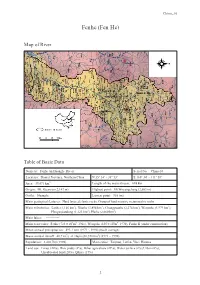

China ―10 Fenhe (Fen He) Map of River Table of Basic Data Name(s): Fenhe (in Huanghe River) Serial No. : China-10 Location: Shanxi Province, Northern China N 35° 34' ~ 38° 53' E 110° 34' ~ 111° 58' Area: 39,471 km2 Length of the main stream: 694 km Origin: Mt. Guancen (2,147 m) Highest point: Mt.Woyangchang (2,603 m) Outlet: Huanghe Lowest point: 365 (m) Main geological features: Hard layered clastic rocks, Group of hard massive metamorphic rocks Main tributaries: Lanhe (1,146 km2), Xiaohe (3,894 km2), Changyuanhe (2,274 km2), Wenyuhe (3,979 km2), Honganjiandong (1,123 km2), Huihe (2,060 km2) Main lakes: ------------ 6 3 6 3 Main reservoirs: Fenhe (723×10 m , 1961), Wenyuhe (105×10 m , 1970), Fenhe II (under construction) Mean annual precipitation: 493.2 mm (1971 ~ 1990) (basin average) Mean annual runoff: 48.7 m3/s at Hejin (38,728 km2) (1971 ~ 1990) Population: 3,410,700 (1998) Main cities: Taiyuan, Linfen, Yuci, Houma Land use: Forest (24%), Rice paddy (2%), Other agriculture (29%), Water surface (2%),Urban (6%), Uncultivated land (20%), Qthers (17%) 3 China ―10 1. General Description The Fenhe is a main tributary of The Yellow River. It is located in the middle of Shanxi province. The main river originates from northwest of Mt. Guanqing and flows from north to south before joining the Yellow River at Wanrong county. It flows through 18 counties and cities, including Ningwu, Jinle, Loufan, Gujiao, and Taiyuan. The catchment area is 39,472 km2 and the main channel length is 693 km. -

Impact of Coal Mining on Karst Water System in North China

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Procedia Earth and Planetary Science 3 ( 2011 ) 293 – 302 2011 Xican International Conference on Fine Geological Exploration and Groundwater & Gas Hazards Control in Coal Mines Impact of Coal Mining on Karst Water System in North China Xiangqing Fang*, Yaojun Fu Hydrogeology Bureau of China Nat ion al Administration of Coal Geology, Handan 056004, China Abstract Based on a large number of data, the paper analysed the influence factors of coal mining for the karst water system in north China, used analytic hierarchy process (AHP) for evaluation of the effect of coal mining on the karst water system, and divided influence degree subareas of State-planed 21 coal mining areas. We also come up with some suggestions on prevention and control measures of principle according to the different influence degrees. ©© 20112011 Published Published by by Elsevier Elsevier Ltd. Ltd. Selection Selection and and/or peer-review peer-review under under responsibility responsibility of China of Xi’an Coal Research Society Institute of China Coal Technology & Engineering Group Corp Keywords: karst-water system in north China, influence degree, prevention and control measures; North China type coalfield and the karst water system in the north are inseparable, there exists three superposition relationships [1]: monoclinal structure, synclinal structure and block-faulting structure. Karst water system in the north is characterized by large scales, numerous components of water resources, the complexity of transformation between water resources, coexistence of water and coal and so on. The karst water resource in the north is not only important water resource, but also is threatening the coal resources. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles the How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China a Disser

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The How and Why of Urban Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 © Copyright by Jonathan Stanhope Bell 2014 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The How and Why of Preservation: Protecting Historic Neighborhoods in China by Jonathan Stanhope Bell Doctor of Philosophy in Urban Planning University of California, Los Angeles, 2014 Professor Anastasia Loukaitou-Sideris, Chair China’s urban landscape has changed rapidly since political and economic reforms were first adopted at the end of the 1970s. Redevelopment of historic city centers that characterized this change has been rampant and resulted in the loss of significant historic resources. Despite these losses, substantial historic neighborhoods survive and even thrive with some degree of integrity. This dissertation identifies the multiple social, political, and economic factors that contribute to the protection and preservation of these neighborhoods by examining neighborhoods in the cities of Beijing and Pingyao as case studies. One focus of the study is capturing the perspective of residential communities on the value of their neighborhoods and their capacity and willingness to become involved in preservation decision-making. The findings indicate the presence of a complex interplay of public and private interests overlaid by changing policy and economic limitations that are creating new opportunities for public involvement. Although the Pingyao case study represents a largely intact historic city that is also a World Heritage Site, the local ii focus on tourism has disenfranchised residents in order to focus on the perceived needs of tourists. -

Environmental Impact Assessment Report

Environmental Impact Assessment Report For Public Disclosure Authorized Changzhi Sustainable Urban Transport Project E2858 v3 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Shanxi Academy of Environmental Sciences Sept, 2011 Public Disclosure Authorized I TABLE OF CONTENT 1. GENERAL ................................................................ ................................ 1.1 P ROJECT BACKGROUND ..............................................................................................1 1.2 B ASIS FOR ASSESSMENT ..............................................................................................2 1.3 P URPOSE OF ASSESSMENT AND GUIDELINES .................................................................4 1.4 P ROJECT CLASSIFICATION ...........................................................................................5 1.5 A SSESSMENT CLASS AND COVERAGE ..........................................................................6 1.6 I DENTIFICATION OF MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL ISSUE AND ENVIRONMENTAL FACTORS ......8 1.7 A SSESSMENT FOCUS ...................................................................................................1 1.8 A PPLICABLE ASSESSMENT STANDARD ..........................................................................1 1.9 P OLLUTION CONTROL AND ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION TARGETS .............................5 2. ENVIRONMENTAL BASELINE ................................ ................................ 2.1 N ATURAL ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................3 -

SARS CHINA Case Distribution by Prefecture-20 May 20031

Source: Ministry of Health, People's Republic of China SARS Case Distribution by Prefecture(City) in China (Accessed 10:00 20 May 2003) No. Area Prefecture Cumulati Level of local Last Remarks (city) ve transmission reported Probable date Cases 1 Beijing 2444 C 20-May 2 Tianjin 175 C 17-May 3 Hebei 217 Shijiazhuang 24 B 20-May Baoding 31 B 18-May Qinhuangdao 5 UNCERTAIN 7-May Langfang 17 A 14-May Cangzhou 1 NO 26-Apr Tangshan 50 B 18-May Chengde 12 A 20-May Zhangjiakou 66 A 16-May Handan 6 NO 18-May Hengshui 1 NO 7-May Xingtai 4 NO 19-May 4 Shanxi 445 Changzhi 4 NO 8-May Datong 5 NO 8-May Jincheng 1 NO 4-May Jinzhong 49 B 15-May Linfen 18 B 4-May Lvliang 2 NO 13-May Shuozhou 4 NO 17-May Taiyuan 338 C 20-May Xinzhou 4 NO 8-May Yangquan 8 A 10-May Yuncheng 12 A 15-May 5 Inner 287 Mongolia Huhehot 148 C 20-May Baotou 14 B 10-May Bayanzhouer 102 C 15-May 1 Wulanchabu 9 B 6-May Tongliao 1 NO 26-May Xilinguole 10 B 17-May Chifeng 3 NO 6-May 6 Liaoning 3 Huludao 1 NO 26-Apr Liaoyang 1 NO 8-May Dalian 1 NO 12-May 7 Jilin 35 Changchun 34 B 17-May Jilin 1 NO 26-May 8 Heilongjiang 0 9 Shanghai 7 NO 10-May 10 Jiangsu 7 Yancheng 1 NO 2-May Xuzhou 1 NO Before 26 April Nantong 1 NO 30-Apr Huai’an 1 NO 2-May Nanjing 2 A 11-May 1st case of local transmission reported on May 10 Suqian 1 NO 8-May 11 Zhejiang 4 Hangzhou 4 NO 8-May 12 Anhui 10 Fuyang 6 NO 2-May Hefei 1 NO 30-Apr Bengbu 2 NO 10-May Anqing 1 NO 5-May 13 Fujian 3 Sanming 1 NO Before 26 April Xiamen 2 NO Before 26 April 14 Jiangxi 1 Ji’an 1 NO 4-May 15 Shandong 1 2 Jinan 1 NO 22-Apr 16 Henan -

The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot

RESEARCH ARTICLE The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013) Junni Wei1*, Alana Hansen2, Qiyong Liu3,4, Yehuan Sun5, Phil Weinstein6, Peng Bi2* 1 Department of Epidemiology, School of Public Health, Shanxi Medical University, Taiyuan, Shanxi, China, 2 Discipline of Public Health, School of Population Health, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 3 State Key Laboratory for Infectious Diseases Prevention and Control, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Beijing, China, 4 Shandong University Climate Change and Health Center, Jinan, Shandong, China, 5 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Public Health, Anhui Medical University, Hefei, Anhui, China, 6 Division of Health Sciences, School of Pharmacy and Medical Sciences, The University of South Australia, Adelaide, Australia OPEN ACCESS * [email protected] (JW); [email protected] (PB) Citation: Wei J, Hansen A, Liu Q, Sun Y, Weinstein P, Bi P (2015) The Effect of Meteorological Variables on the Transmission of Hand, Foot and Mouth Abstract Disease in Four Major Cities of Shanxi Province, China: A Time Series Data Analysis (2009-2013). Increased incidence of hand, foot and mouth disease (HFMD) has been recognized as a PLoS Negl Trop Dis 9(3): e0003572. doi:10.1371/ journal.pntd.0003572 critical challenge to communicable disease control and public health response. This study aimed to quantify the association between climate variation and notified cases of HFMD in Editor: Rebekah Crockett Kading, Genesis Laboratories, UNITED STATES selected cities of Shanxi Province, and to provide evidence for disease control and preven- tion. -

Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure

sustainability Article Evaluation of Sustainable Development of Resources-Based Cities in Shanxi Province Based on Unascertained Measure Yong-Zhi Chang and Suo-Cheng Dong * Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-10-64889430; Fax: +86-10-6485-4230 Academic Editor: Marc A. Rosen Received: 31 March 2016; Accepted: 16 June 2016; Published: 22 June 2016 Abstract: An index system is established for evaluating the level of sustainable development of resources-based cities, and each index is calculated based on the unascertained measure model for 11 resources-based cities in Shanxi Province in 2013 from three aspects; namely, economic, social, and resources and environment. The result shows that Taiyuan City enjoys a high level of sustainable development and integrated development of economy, society, and resources and environment. Shuozhou, Changzhi, and Jincheng have basically realized sustainable development. However, Yangquan, Linfen, Lvliang, Datong, Jinzhong, Xinzhou and Yuncheng have a low level of sustainable development and urgently require a transition. Finally, for different cities, we propose different countermeasures to improve the level of sustainable development. Keywords: resources-based cities; sustainable development; unascertained measure; transition 1. Introduction In 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) proposed the concept of “sustainable development”. In 1996, the first official reference to “sustainable cities” was raised at the Second United Nations Human Settlements Conference, namely, as being comprised of economic growth, social equity, higher quality of life and better coordination between urban areas and the natural environment [1]. -

Chinacoalchem

ChinaCoalChem Monthly Report Issue May. 2019 Copyright 2019 All Rights Reserved. ChinaCoalChem Issue May. 2019 Table of Contents Insight China ................................................................................................................... 4 To analyze the competitive advantages of various material routes for fuel ethanol from six dimensions .............................................................................................................. 4 Could fuel ethanol meet the demand of 10MT in 2020? 6MTA total capacity is closely promoted ....................................................................................................................... 6 Development of China's polybutene industry ............................................................... 7 Policies & Markets ......................................................................................................... 9 Comprehensive Analysis of the Latest Policy Trends in Fuel Ethanol and Ethanol Gasoline ........................................................................................................................ 9 Companies & Projects ................................................................................................... 9 Baofeng Energy Succeeded in SEC A-Stock Listing ................................................... 9 BG Ordos Started Field Construction of 4bnm3/a SNG Project ................................ 10 Datang Duolun Project Created New Monthly Methanol Output Record in Apr ........ 10 Danhua to Acquire & -

RPD: People's Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns

Resettlement Planning Document Updated Resettlement Plan Document Stage: Final Project Number: 42383 January 2011 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Small Cities and Towns Development Demonstration Sector Project– Youyu County Subproject Prepared by Youyu County Project Management Office (PMO) The updated resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Resettlement Plan Shanxi Small Cities & Towns Development Demonstration Project Resettlement Plan For Youyu County Subproject Youyu County Development and Reform Bureau 30 September, 2008 Shanxi Urban & Rural Design Institute 1 Youyu County ADB Loan Financed Project Management Office Endorsement Letter of Resettlement Plan Youyu County Government has applied for a loan from the ADB to finance the District Heating, Drainage and wastewater network, River improvement, Roads and Water supply Projects. Therefore, the projects must be implemented in compliance with the guidelines and policies of the Asian Development Bank for Social Safeguards. This Resettlement Plan is in line with the key requirements of the Asian Development Bank and will constitute the basis for land acquisition, house demolition and resettlement of the project. The Plan also complies with the laws of the People’s Republic of China, Shanxi Province and Youyu County regulations, as well as with some additional measures and the arrangements for implementation and monitoring for the purpose of achieving better resettlement results. Youyu County ADB Loan Project Office hereby approves the contents of this Resettlement Plan and guarantees the implementation of land acquisition, house demolition, resettlement, compensation and fund budget will comply with this plan. -

People's Republic of China: Shanxi Road Development II Project

Completion Report Project Number: 34097 Loan Number: 1967 August 2008 People’s Republic of China: Shanxi Road Development II Project CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit – yuan (CNY) At Appraisal At Project Completion (14 November 2002) (as of 6 March 2008) CNY1.00 = $0.1208 $0.14047 $1.00 = CNY8.277 CNY7.119 ABBREVIATIONS AADT – average annual daily traffic ADB – Asian Development Bank CSE – chief supervision engineer CSEO – chief supervision engineer office DCSE – deputy chief supervision engineer EIA – environmental impact assessment EIRR – economic internal rate of return FIRR – financial internal rate of return GDP – gross domestic product HDM-4 – highway design and maintenance standards model, version 4 ICB – international competitive bidding IDC – interest and other charges during construction IEE – initial environmental examination IRI – international roughness index MOC – Ministry of Communications NCB – national competitive bidding NTHS – national trunk highway system O&M – operation and maintenance PCR – project completion review PPMS – project performance management system PRC – People’s Republic of China PRIS – poverty reduction impact study PRMP – poverty reduction monitoring program REO – resident engineer office RP – resettlement plan SCD – Shanxi Communications Department SCF – standard conversion factor SEIA – summary environmental impact assessment SEPA – State Environment Protection Administration SFB – Shanxi Finance Bureau SHEC – Shanxi Hou-yu Expressway Construction Company Limited SKCC – Shaanxi Kexin Consultant Company SPG – Shanxi provincial government VOC – vehicle operating cost YWNR – Yuncheng Wetlands Nature Reserve WEIGHTS AND MEASURES mu – A traditional land area measurement, it is equivalent to 666.66 square meters, or 0.1647 acres, or 0.066 of a hectare. m/km – meters per kilometer mg/m3 – milligram per meter cube p.a. -

Up to July 13, 2007)

Current Location :Project Information Newly Approved Projects by DNA of China (Total: 76) (Up to July 13, 2007) Estimated Project Ave. GHG No. Project Name Project Owner CER Buyer Type Reduction (tCO2e/y) Fugong Jiacheng Fugong Mukeji Hydropower Renewable Carbon Asset Management 1 Hydropower 102,781 Project energy Sweden AB Development Co.,Ltd. Yuexi County Liyuan Yuexi Dayan Small Renewable Carbon Asset Management 2 Hydropower 48,722 Hydropower Project energy Sweden AB Development Co.,Ltd. Kunming Dongjiao Methane Kunming Huan Ye 3 Baishuitang LFG Treatment recovery & Project Development Asja Ambiente Italia S.P.A(Italy) 64,302 and Power Generation Project utilization Co.,Ltd. Jiuzhaigou Electric Sichuan Shuanghe Renewable 4 Power Development Marubeni Corporation(Japan) 297,313 Hydropower Project energy Ltd Co. Shandong Luneng Baiyun’ebo 45MW Wind Farm Renewable 5 Development Group Arreon Carbon UK Ltd 96,468 Project energy Co.,Ltd. Guangxi Baise Tianlin Baile Renewable Tianlin Baile River 6 RWE Power AG(Germany) 48,079 Hydropower Station energy Hydropower Co.,Ltd. Methane Anhui Qidong Coal Mine Wanbei Coal and Renaissance Carbon Investment 7 recovery & 57,208 Methane Utilization Project Power Co.,Ltd. Ltd(UK) utilization The Natural Gas-stream Energy saving Beijing Jing Feng Gas Combined Cycle Electric 8 and efficiency Fired Power Company RWE Power AG(Germany) 633,341 Power Project of Beijing Third improvement Ltd. Thermal Power Plant Luzhou Jiale Yuanxing Renewable 9 Yuanxing Hydropower Project Electic Power EcoSecurities Group Plc(UK) 50,752 energy Development Co.,Ltd Sichuan Liangtan Hydropower Renewable Sichuan Guang’an 10 EcoSecurities Group Plc(UK) 82,229 Station Second Phase Project energy AAA Public Co.,Ltd. -

Environmental Impact Assessment Executive Summary

SFG3333 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental Impact Assessment Executive Summary For Public Disclosure Authorized Shanxi Gas Utilization Project - Yangcheng Gas Utilization Subproject (Draft) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Coal Chemistry Institute of China Academy of Sciences Mar. 2017 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Shanxi Gas Utilization Project – Yangcheng Gas Utilization Subproject TABLE OF CONTENT 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................3 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 3 1.2 ENVIRONMENTAL POLICIES, LAWS AND REGULATIONS --------------------------------------------------- 3 1.2.1 Laws and Regulations ...................................................................................................................... 3 1.2.2 Safeguard Policies and EHS Guideline ........................................................................................... 3 1.2.3 Applicable Standards ....................................................................................................................... 4 2. PROJECT DESCRIPTION .................................................................................................4 2.1 PROJECT COMPOSITION ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 4 2.2 GAS CONSUMPTION ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------