Sep Uncompanion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Assembly of North Carolina Session 2007

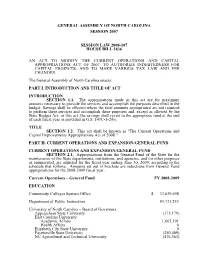

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2007 SESSION LAW 2008-107 HOUSE BILL 2436 AN ACT TO MODIFY THE CURRENT OPERATIONS AND CAPITAL APPROPRIATIONS ACT OF 2007, TO AUTHORIZE INDEBTEDNESS FOR CAPITAL PROJECTS, AND TO MAKE VARIOUS TAX LAW AND FEE CHANGES. The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: PART I. INTRODUCTION AND TITLE OF ACT INTRODUCTION SECTION 1.1. The appropriations made in this act are for maximum amounts necessary to provide the services and accomplish the purposes described in the budget. Savings shall be effected where the total amounts appropriated are not required to perform these services and accomplish these purposes and, except as allowed by the State Budget Act, or this act, the savings shall revert to the appropriate fund at the end of each fiscal year as provided in G.S. 143C-1-2(b). TITLE SECTION 1.2. This act shall be known as "The Current Operations and Capital Improvements Appropriations Act of 2008." PART II. CURRENT OPERATIONS AND EXPANSION/GENERAL FUND CURRENT OPERATIONS AND EXPANSION/GENERAL FUND SECTION 2.1. Appropriations from the General Fund of the State for the maintenance of the State departments, institutions, and agencies, and for other purposes as enumerated, are adjusted for the fiscal year ending June 30, 2009, according to the schedule that follows. Amounts set out in brackets are reductions from General Fund appropriations for the 2008-2009 fiscal year. Current Operations – General Fund FY 2008-2009 EDUCATION Community Colleges System Office $ 33,639,698 Department of Public Instruction -

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M. Bartos, Administrator Governor Roy Cooper Office of Archives and History Secretary Susi H. Hamilton Deputy Secretary Kevin Cherry July 31, 2020 Braden Ramage [email protected] North Carolina Army National Guard 1636 Gold Star Drive Raleigh, NC 27607 Re: Demolish & Replace NC Army National Guard Administrative Building 116, 116 Air Force Way, Kure Beach, New Hanover County, GS 19-2093 Dear Mr. Ramage: Thank you for your submission of July 8, 2020, transmitting the requested historic structure survey report (HSSR), “Historic Structure Survey Report Building 116, (former) Fort Fisher Air Force Radar Station, New Hanover County, North Carolina”. We have reviewed the HSSR and offer the following comments. We concur that with the findings of the report, that Building 116 (NH2664), is not eligible for the National Register of Historic Places for the reasons cited in the report. We have no recommendations for revision and accept this version of the HSSR as final. Additionally, there will be no historic properties affected by the proposed demolition of Building 116. Thank you for your cooperation and consideration. If you have questions concerning the above comment, contact Renee Gledhill-Earley, Environmental Review Coordinator, at 919-814-6579 or [email protected]. In all future communication concerning this project, please cite the above referenced tracking number. Sincerely, Ramona Bartos, Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer cc Megan Privett, WSP USA [email protected] Location: 109 East Jones Street, Raleigh NC 27601 Mailing Address: 4617 Mail Service Center, Raleigh NC 27699-4617 Telephone/Fax: (919) 814-6570/807-6599 HISTORIC STRUCTURES SURVEY REPORT BUILDING 116, (FORMER) FORT FISHER AIR FORCE RADAR STATION New Hanover County, North Carolina Prepared for: North Carolina Army National Guard Claude T. -

Newsletter Volume 15 No

Federal Point Historic Preservation Society P.O. Box 623, Carolina Beach, North Carolina 28428 Phone: 910-458-0502 e-mail:[email protected] Newsletter Volume 15 No. 6 June, 2008 Darlene Bright, editor Annual June Picnic Monday June 16, 2008 In lieu of our regular monthly meeting, the Federal Point Historic Preservation Society will hold its annual covered dish supper on Monday, June 16 at 6:30 pm at the Federal Point History Center, 1121-A North Lake Park Blvd., adjacent to Carolina Beach Town Hall. Members and the general public are cordially invited. Bring a friend and your favorite covered dish. It is important that everyone be present as we will be voting on officers and board members for the 2008- 2009 fiscal year. Last Month Danielle Wallace of the USS North Carolina Battleship Memorial gave an excellent presentation on the Battleship and the “Floating City.” She revealed some of the secrets held by the Battleship as new compartments are explored and opened to the public. Danielle is not new to the area. She previously worked at the Fort Fisher Museum and the North Carolina Aquarium at Fort Fisher, and we feel that she is proving to be a great asset in her work at the North Carolina Battleship Memorial. Danielle, keep up the good work! North Carolina’s Role in World War II By Sarah McCulloh Lemmon State Department of Archives and History, 1964 Even before Pearl Harbor brought the United States into the war as an avowed belligerent, North Carolina had felt the impact of preparations for military expansion. -

Department of Defense Appropriations Bill, 1999

1 105TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 105±591 "! DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 1999 R E P O R T OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 4103] JUNE 22, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 49±216 WASHINGTON : 1998 105TH CONGRESS REPORT 2d Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 105±591 "! DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 1999 R E P O R T OF THE COMMITTEE ON APPROPRIATIONS together with DISSENTING VIEWS [To accompany H.R. 4103] JUNE 22, 1998.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE APPROPRIATIONS BILL, 1999 C O N T E N T S Page Bill Totals ................................................................................................................. 1 Committee Budget Review Process ........................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................... 4 Rationale for the Committee Bill .................................................................... 6 Major Committee Recommendations ...................................................................... 7 Addressing High Priority Unfunded Shortfalls .............................................. 7 Ensuring a Quality, Ready Force .................................................................... 7 Modernization -

Tar Heel Junior Historian North Carolina History for Students Spring 2008 Volume 47, Number 2

F l «• ■■ si/a c. a Produced by the North (duroliri Spriny20013 • C; documents learingwouse APR 1 o 2008 “"fis\ [ Tar Heel Junior Historian North Carolina History for Students Spring 2008 Volume 47, Number 2 On the cover: Marine Gunnery Sergeant Maynard P- Daniels Jr., of Wanchese, on duty in the south¬ west Pacific. Daniels, age twenty-six, won a state Golden Gloves boxing title as a Wake Forest College student before turning pro. He enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves in 1936 and was Introduction: World 1 called to active duty in late 1940. At right: Staff Sergeant John W. Moffitt, of War II Touched Lives Greensboro, in the nose of a B-26 Marauder plane. in Every Community The twenty-two-year-old bombardier had recently by Dr. Annette Ayers llL scuffled with Nazi fighters over Germany, where the Ninth Army Air Force successfully attacked a railway bridge on a German supply route. Images North Carolina’s Wartime courtesy of the North Carolina Museum of History. Blimps over Elizabeth City Miracle: Defending by Stephen D. Chalker 5 the Nation State of North Carolina 25 by Dr. John S. Duvall Michael F. Easley, Governor Beverly E. Perdue, Lieutenant Governor Enemies and Friends: POWs in the Tar Heel State Courage above and Department of Cultural Resources 26 by Dr. Robert D. Billinger Jr. Lisbeth C. Evans, Secretary beyond the Call of Duty: Staci T. Meyer, Chief Deputy Secretary 9 Tar Heels in World War II by Lieutenant Colonel Hospital Cars Rode Office of Archives and History Jeffrey J. -

World War II in North Carolina

ALLEGHANY CURRITUCK CAMDEN Weeksville Naval SURRY NORTHAMPTON GATES ASHE E World War II ELL Air Station (LTA) WARREN STOKES C P ASQUOTCG N Chatham Manufacturing HERTFORD P CASW PERSON E N ROCKINGHAM VA R Q Consolidated Vultee Principal Installations, Camps, Fairchild Aircraft HALIFAX U A WATAUGA WILKES C I NK GRANVILLE M Aircraft Corporation FORSYTH GUILFORD Company H A YADKIN O N Camp Butner BERTIE S Industries, and Facilities C A MW MITCHELL C A AVERY N FRANKLIN USMC YA CALDWELL Army Air Force National NASH Air Station Manteo N N DAVIE A DURHAM C ORANGE EDGECOMBE Naval Air Station ALAMANCE Munitions E National Carbon Overseas Y ALEXANDER MADISON Electrode Plant VIDSON Replacement Company MAR WASHINGTON TYRRELL IREDELL DA Raleigh-Durham TIN HA Depot (O.R.D.) DARE U-85 CHATHAM Army Airfield C YWOOD WILSON April 14, 1942 BUNCOMBEC MCDOWELL BURKE CATAWBA H ROWAN RANDOLPH WAKE USS Roper Seymour Johnson Field BEAUFORT HYDE AIN CLEVELAND JOHNSTON SW MECKLENBURG RUTHERFORD LINCOLN LEE A GREENE PITT Dayton Rubber MONTGOMER Company A CABARRUS MOORE GRAHAM HENDERSON A HARNETT JACKSON GASTON Carolina Aluminum Co. Cape Hatteras ANIA V POLK STANLY WAYNE A Y A Pope Field CRAVEN N Knollwood Field LENOIR MACON FORT BRAGG CG U-701 RICHMOND Camp Battle PAMLICO TRANSYL Army Air Force CUMBERLAND July 7, 1942 CHEROKEE CLAY Ecusta UNION Ocracoke Redistribution Camp Mackall JONES Barbour Boat Works American Hudson Paper Co. HOKE SAMPSON Naval Air Morris Field ANSON M Aircraft Rest Camp DUPLIN Cherry Point Station Aluminum Company Camp Sutton A of America - Marine Air Base ONSLOW Hydroelectric Plant CARTERET Fort SCOTLAND U-576 Laurinburg-Maxton Camp Lejeune Macon ROBESON July 15, 1942 Army Air Base BLADEN Morehead City Camp Davis 2 U.S. -

Division E—Military Construction and Veterans Affairs and Related Agen- Cies Appropriations Act, 2009

[House Appropriations Committee Print] Consolidated Security, Disaster Assistance, and Continuing Appropriations Act, 2009 (H.R. 2638; P.L. 110–329) DIVISION E—MILITARY CONSTRUCTION AND VETERANS AFFAIRS AND RELATED AGEN- CIES APPROPRIATIONS ACT, 2009 (703) VerDate Aug 31 2005 04:29 Oct 22, 2008 Jkt 044807 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6601 Sfmt 6601 E:\HR\OC\A807P6.XXX A807P6 rfrederick on PROD1PC67 with HEARING VerDate Aug 31 2005 04:29 Oct 22, 2008 Jkt 044807 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6601 Sfmt 6601 E:\HR\OC\A807P6.XXX A807P6 rfrederick on PROD1PC67 with HEARING CONTENTS, DIVISION E Page Legislative Text: Title I—Department of Defense ...................................................................... 709 Title II—Department of Veterans Affairs ...................................................... 721 Title III—Related Agencies .............................................................................. 732 Title IV—General Provisions ........................................................................... 734 Explanatory Statement: Title I—Department of Defense ...................................................................... 736 Title II—Department of Veterans Affairs ...................................................... 748 Title III—Related Agencies .............................................................................. 756 Title IV—General Provisions ........................................................................... 757 Earmark Disclosure ......................................................................................... -

North Carolina Sentinel Landscape Committee

NORTH CAROLINA SENTINEL LANDSCAPE COMMITTEE 2019 ANNUAL LEGISLATIVE REPORT August 30, 2019 Agriculture Commissioner – Steve Troxler – Chair Executive Director of the Wildlife Resources Commission – Gordon Myers – Vice Chair Chief Deputy Secretary of Natural and Cultural Resources – D. Reid Wilson – Secretary Assistant Secretary of Military and Veterans Affairs – Ariel Aponte Dean of the College of Natural Resources at NC State University – Dr. Mary Watzin Representative of the North Carolina Sentinel Landscape Partnership – Chester Lowder Pursuant to Section 3.19.(f) of Senate Bill 131 / S.L. 2017-10 … The Committee shall report on its activities conducted to implement this section, including any findings, recommendations, and legislative proposals, to the North Carolina Military Affairs Commission and the Agriculture and Forestry Awareness Study Commission beginning September 1, 2017, and annually thereafter, until such time as the Committee completes its work. 2019 Annual Report North Carolina Sentinel Landscape Committee Table of Contents What are Sentinel Landscapes? 3 Purpose of the North Carolina Sentinel Landscape Committee 4 Committee Members 5 N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Report 6-8 N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission Report 9-10 N.C. Department of Natural and Cultural Resources Report 11-13 N.C. Department of Military and Veteran Affairs Report 14 College of Natural Resources at N.C. State University Report 15-16 N.C. Sentinel Landscape Partnership Report 17-18 Meeting Summaries 19-26 2 2019 Annual Report North Carolina Sentinel Landscape Committee What are Sentinel Landscapes? The Eastern North Carolina Sentinel Landscape benefits agriculture, forestry, wildlife, and the military - In 2016, the federal government designated 33 North Carolina counties as a Sentinel Landscape. -

The Integrated Training Area Management (ITAM) Regional Support Center (RSC) Program

The Integrated Training Area Management (ITAM) Regional Support Center (RSC) Program. The United States Army must be ready to perform at the highest level in a variety of environments. Army training is designed to challenge soldiers, leaders, and units alike. The Army relies on land to achieve its training and testing objectives and maintain force readiness. In this day and age, the Army has faced unparalleled threats to its ability to train. Increased environmental regulations and the encroachment of the public sector onto installations have made the management of training lands a fine and exact science. A happy medium must be found between the interests of environmentalists, the public and Army personnel wishing to provide the best training for our troops in a fiscally responsible manner. The Army Integrated Training Area Management (ITAM) program deals with issues regarding the prudent management of training and testing lands. The goals of the ITAM program include the following: • Achieve optimal sustained use of lands for the execution of realistic training, by providing a sustainable core capability, which balances usage, condition, and level of maintenance • Implement a management and decision-making process, which integrates Army training and other mission requirements for land use with sound natural and cultural resources management • Advocate proactive conservation and land management p • Align Army training land management priorities with the Army training, testing, and readiness priorities. A popular medium in trying to display management practices and stewardship techniques on Army installations is through the use of maps. One component of the ITAM program is the use of GIS (Geographic Information Systems). -

The Military 'S Broad Impact on Eastern North Carolina

More Than Economics: The Military 's Broad Impact on Eastern North Carolina by Renee Elder 64 NORTH CAROLINA INSIGHT Executive Summary n its approach to the U.S. Department of Defense Base Realignment and Closure process, with thousands of military and civilian jobs on the line, North Carolina attempted to brand itself as "the most military friendly state in the nation." And, of the state's three regions, the East is by far the friendliest. Home to six major military bases and several smaller installations, the East plays host to some 116,000 uniformed troops and more than 21,000 civilian workers, pumping billions of dollars into the economy of the state's poorest region. Indeed, approximately one-eighth of the nation's troop strength is stationed in Eastern North Carolina (116,000 soldiers in Eastern North Carolina out of 780,000 total troops). The military presence provides a great deal of pride in the region's role in defending freedom, and the nation's defense is vital to every citizen. But the heavy military pres- ence also produces broad impacts. What are some of these impacts, and how do they affect Eastern North Carolina's military towns and counties? The Center examined 12 areas of impact: economic impact; defense contracts; impact on ports; impact on sales taxes and property taxes; impact on taxpayer financed services and on growth and housing; impact on the public schools; impact of military spouses and retirees on the local workforce; rates of crime, domestic violence, and child abuse; race relations and the military; presence of drinking establishments, pawn shops, and tattoo parlors; environmental impact; and air space restrictions. -

Military Collection Xii. World War Ii Papers, 1939 – 1947 Xiv

MILITARY COLLECTION XII. WORLD WAR II PAPERS, 1939 – 1947 XIV. PRIVATE COLLECTIONS Some of the materials listed in this old finding aid have been reprocessed with new Military Collection WWI Papers collection numbers. For those that have been reprocessed, they were removed from this finding aid, leaving box number gaps. For information on the reprocessed collections, contact the State Archives of North Carolina’s Reference Unit or the Military Collection Archivist. —Matthew M. Peek, Military Collection Archivist October 2017 Box No. Contents 1 John R. Conklin Papers. Papers reflecting the service of Cpl. John R. Conklin of Ohio in the 345th Infantry Regiment, 87th Division, including personal correspondence, 1943-1947, n.d.; service medals and ribbons, including two Bronze Stars; and a disassembled “War Scrapbook” that contained official correspondence and documents (including honorable discharge), 1941-1948, n.d.; photographs; chits; identification cards; newspaper clippings (originals replaced by Xerox copies); and foreign paper currency. 2 William J. Jasper Papers. Contains manuscript autobiography of the service of Lt. William J. Jasper in the U.S. Navy during World War II and the Korean War, 1943-1955. See World War II vertical files for Xerox copies of Jasper’s service records and newspaper articles relating to the USS Antietam. Charles M. Johnson Jr. Papers. Papers reflecting the service of PFC Charles M. Johnson Jr. of Raleigh (Wake County) in the 79th Division, including typescript reminiscence titled, “The World War II Years: My Story”; two copy print photographs; panoramic photograph of Battery B, 5th Battalion, 2nd Training Regiment, Fort Bragg, 1943 [removed and filed as MilColl.WWII.Panoramas.2]; twelve war ration books (various names) with paper envelope carrier; and special section from The Times (London) on the fiftieth anniversary of D-Day. -

WWII NC Military Base Newsletters Now Online

H-War All WWII NC Military Base Newsletters Now Online Discussion published by Matthew Peek on Friday, January 17, 2020 A collection of North Carolina military installation camp newsletters and newspapers from World War II are now available online as part of the State Archives of North Carolina’s Military Collection. As part of a two-year digitization project begun in 2018 to commemorate the 75th anniversary of World War II, the State Archives has been digitizing unique, and in some cases, complete runs of newsletter issues published by military officials and various base units during the war, such as Camp Lejeune, Camp Davis, Morris Field, and Elizabeth City Naval Air Station. Most of these newsletters were collected between 1942 and 1947 by the State Archives, sent from the various military base public relations offices or soldiers stationed at those installations. The newsletters have been available for use by the public at the State Archives since 1947 for research. However, the State Archives saw a need to place all of the newsletters online in order to increase statewide, national, and international use of their invaluable information. Many of these newsletters were informally published by various units while briefly stationed at bases such as Fort Bragg. Much of the information and news leaned toward a more humorous and playful side. One of the most important things about the newsletters is that they contain names of individuals in military units, civilian workers in various departments on base, female civilian and military personnel working at the installations, and news of casualties formerly stationed at those bases.