Editorial the Molecular Genetics of the Dystonias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dystonia and Chorea in Acquired Systemic Disorders

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.65.4.436 on 1 October 1998. Downloaded from 436 J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1998;65:436–445 NEUROLOGY AND MEDICINE Dystonia and chorea in acquired systemic disorders Jina L Janavs, Michael J AminoV Dystonia and chorea are uncommon abnormal Associated neurotransmitter abnormalities in- movements which can be seen in a wide array clude deficient striatal GABA-ergic function of disorders. One quarter of dystonias and and striatal cholinergic interneuron activity, essentially all choreas are symptomatic or and dopaminergic hyperactivity in the nigros- secondary, the underlying cause being an iden- triatal pathway. Dystonia has been correlated tifiable neurodegenerative disorder, hereditary with lesions of the contralateral putamen, metabolic defect, or acquired systemic medical external globus pallidus, posterior and poste- disorder. Dystonia and chorea associated with rior lateral thalamus, red nucleus, or subtha- neurodegenerative or heritable metabolic dis- lamic nucleus, or a combination of these struc- orders have been reviewed frequently.1 Here we tures. The result is decreased activity in the review the underlying pathogenesis of chorea pathways from the medial pallidus to the and dystonia in acquired general medical ventral anterior and ventrolateral thalamus, disorders (table 1), and discuss diagnostic and and from the substantia nigra reticulata to the therapeutic approaches. The most common brainstem, culminating in cortical disinhibi- aetiologies are hypoxia-ischaemia and tion. Altered sensory input from the periphery 2–4 may also produce cortical motor overactivity medications. Infections and autoimmune 8 and metabolic disorders are less frequent and dystonia in some cases. To date, the causes. Not uncommonly, a given systemic dis- changes found in striatal neurotransmitter order may induce more than one type of dyski- concentrations in dystonia include an increase nesia by more than one mechanism. -

The Dystonias

LE JOURNAL CANADIEN DES SCIENCES NEUROLOGIQUES SUBJECT REVIEW The Dystonias Edith G. McGeer and Patrick L. McGeer Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 1988; 15: 447-483 Contents This review is intended for both the practitioner and the sci entist. Its purpose is to summarize current knowledge regarding the various forms of dystonia, as well as the pathology known Introduction to produce the syndrome in specialized circumstances. Histopathological and brain imaging studies The low incidence of the disorder, its prolonged course, and the difficulty of accurate diagnosis has precluded the type of Sleep and other physiological studies systematic investigation that is possible with many other disor Chemical pathology ders. Yet such systematic investigation is essential if the myster Brain studies ies surrounding dystonia are to be unravelled and methods of CSF studies treatment improved. Blood studies Dystonia has been defined by the Scientific Advisory Board Urine studies of the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation as a syndrome of Fibroblast studies sustained muscle contraction, frequently causing twisting and Miscellaneous repetitive movements, or abnormal posture. It is a clinical term Therapy and not a disease description. It refers to all anatomical forms, whether they involve generalized musculature or only focal Iatrogenic dystonia groups. Although dystonia appears as part of the syndrome in a Possible animal models of dystonia number of disease states, it is idiopathic dystonia, where inheri Summary tance is a major factor, that has aroused the greatest medical interest. This review emphasizes recent literature and those aspects which may contribute to an understanding of the under 1. INTRODUCTION lying mechanisms of dystonic movement. -

Botulinum Toxin

Clinical Criteria Subject: Botulinum Toxin Document #: ING-CC-0032 Publish Date: 06/15/202001/25/2021 Status: Revised Last Review Date: 05/15/202012/14/2020 Table of Contents Overview Coding References Clinical criteria Document history Overview This document addresses the use of botulinum toxin agents: Dysport (abobotulinumA), Xeomin (incobotulinumtoxin A), Botox (onabotulinumtoxin A), and Myobloc (rimabotulinumtoxin B). Botulinum is a family of toxins produced by the anaerobic organism Clostridia botulinum. There are seven distinct serotypes designated as type A, B, C-1, D, E, F, and G. In this country, four preparations of botulinum are available, produced by two different strains of bacteria: type A (Botox [onabotulinumtoxinA], Dysport [abobotulinumtoxinA], and Xeomin [incobotulinumtoxinA]) and type B (Myobloc [rimabotulinumtoxinB]). When administered intramuscularly, all botulinum toxins reduce muscle tone by interfering with the release of acetylcholine from nerve endings. However, it should be noted that these drugs are not interchangeable and the potency ratios for dosing cannot be converted. Careful adherence to the specific instructions for dosing in the package insert is recommended. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved label for Botox states that it is indicated for the treatment of cervical dystonia in adults to reduce the severity of abnormal head position and neck pain; primary axillary hyperhidrosis that is inadequately managed with topical agents; strabismus and blepharospasm associated with dystonia, -

Neuropathological Features of Genetically

Neuropathological features of genetically confirmed DYT1 dystonia: Investigating disease-specific inclusions Reema Paudel, UCL Institute of Neurology Aoife Kiely, UCL Institute of Neurology Abi Li, UCL Institute of Neurology Tammaryn Lashley, UCL Institute of Neurology Rina Bandopadhyay, UCL Institute of Neurology John Hardy, UCL Institute of Neurology Hyder Jinnah, Emory University Kailash Bhatia, UCL Institute of Neurology Henry Houlden, UCL Institute of Neurology Janice L. Holton, UCL Institute of Neurology Journal Title: Acta Neuropathologica Communications Volume: Volume 2, Number 1 Publisher: BioMed Central | 2014-01-27, Pages 159-159 Type of Work: Article | Final Publisher PDF Publisher DOI: 10.1186/s40478-014-0159-x Permanent URL: https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/rz52g Final published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40478-014-0159-x Copyright information: © 2014 Paudel et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access work distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Accessed September 25, 2021 4:11 AM EDT Paudel et al. Acta Neuropathologica Communications 2014, 2:159 http://www.actaneurocomms.org/content/2/1/159 RESEARCH Open Access Neuropathological features of genetically confirmed DYT1 dystonia: investigating disease- specific inclusions Reema Paudel1, Aoife Kiely2, Abi Li2, Tammaryn Lashley2, Rina Bandopadhyay2, John Hardy1, Hyder A Jinnah3, Kailash Bhatia1, Henry Houlden1 and Janice L Holton1,2* Abstract Introduction: Early onset isolated dystonia (DYT1) is linked to a three base pair deletion (ΔGAG) mutation in the TOR1A gene. Clinical manifestation includes intermittent muscle contraction leading to twisting movements or abnormal postures. Neuropathological studies on DYT1 cases are limited, most showing no significant abnormalities. -

JAMA Neurology Pages 613-732

In This Issue June 2015 Volume 72, Number 6 JAMA Neurology Pages 613-732 Research Opinion Antibodies to Clustered AChRs and MG 642 Viewpoint Rodríguez Cruz and colleagues determine the diagnostic 623 Neurology and the Aff ordable Care Act usefulness of cell-based assays (CBAs) in the diagno- D Gold and Coauthors sis of myasthenia gravis (MG) and compare the clinical 624 Political Correctness of Medical features of patients with antibodies only to clustered Documentation acetylcholine receptors (AChRs) with those of patients JR Berger with seronegative MG. Radioimmunoprecipitation as- Editorial say (RIPA) and CBA were used to test for standard AChR 626 The Human Alzheimer Disease antibodies and antibodies to clustered AChRs in 138 patients. Cell-based assay is a use- Project: A New Call to Arms ful procedure in the routine diagnosis of RIPA-negative MG, particularly in children, and RN Rosenberg ad RC Petersen patients with antibodies only to clustered AChRs appear to be younger and have milder 628 Cognition and Quality-of-Life disease than other patients with MG. Editorial perspective in support of these data is pro- Outcomes in the Targeted Temperature vided by Steven Vernino, MD, PhD. Management Trial for Cardiac Arrest V Aiyagari and MN Diringer Editorial 630 630 Unraveling the Enigma of Continuing Medical Education jamanetworkcme.com Seronegative Myasthenia Gravis S Vernino Biogenesis and Myogenesis in SMA 666 631 Status Epilepticus AC Jongeling and Coauthors Ripolone and coauthors investigate mitochondrial dys- function in a large series of muscle biopsy samples from Clinical Review & Education patients with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). They stud- ied quadriceps muscle samples from 24 patients with Images in Neurology genetically documented SMA and paraspinal muscle samples from 3 patients with SMA-II undergoing surgery or scoliosis correction. -

Blepharospasm-Oromandibular Dystonia Syndrome (Brueghel's Syndrome) a Variant of Adult-Onset Torsion Dystonia?

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.39.12.1204 on 1 December 1976. Downloaded from Journal ofNeutrology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 1976, 39, 1204-1209 Blepharospasm-oromandibular dystonia syndrome (Brueghel's syndrome) A variant of adult-onset torsion dystonia? C. D. MARSDEN From the University Department oJ Neurology, Institute ofPsychiatry, and King's College Hospital Medical School, Denmark Hill, London SYNOPSIS Thirty-nine patients with the idiopathic blepharospasm-oromandibular dystonia syndrome are described. All presented in adult life, usually in the sixth decade; women were more commonly affected than men. Thirteen had blepharospasm alone, nine had oromandibular dystonia alone, and 17 had both. Torticollis or dystonic writer's cramp preceded the syndrome in two patients. by guest. Protected copyright. Eight otherpatients developed torticollis, dystonic posturing ofthe arms, or involvement ofrespiratory muscles. No cause or hereditary basis for the illness were discovered. The evidence to indicate that this syndrome is due to an abnormality of extrapyramidal function, and that it is another example of adult-onset focal dystonia akin to spasmodic torticollis and dystonic writer's cramp, is discussed. Idiopathic blepharospasm is well recognised, but R. E. Kelly for pointing out that Pieter Brueghel, the idiopathic oromandibular dystonia is not. The latter Elder, clearly recognised the syndrome (Fig. 1). More consists of prolonged spasms of contraction of the recently Altrocchi (1972) described two patients with muscles of the mouth and jaw. These dystonic move- isolated oromandibular dystonia, and Paulson (1972) ments appear to be distinct from the chewing, lip reported three patients with blepharospasm and smacking, and tongue rolling choreiform movements oromandibular dystonia. -

Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary (Idiopathic) Dystonia

Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of primary (idiopathic) dystonia Report by an EFNS MDS-ES Task Force Abstract Objectives: To provide a revised version of earlier guidelines published in 2006. Background: Primary dystonia and dystonia plus syndromes are chronic and often disabling conditions with a widespread spectrum mainly in young people. Search strategy: Computerised MEDLINE and EMBASE literature reviews (up to July 2009) were conducted. The Cochrane Library was searched for relevant citations. Diagnosis: The diagnosis of dystonia is clinical, based on the recognition of specific features. Diagnosis and classification of dystonia are highly relevant for providing appropriate management, prognostic information and genetic counselling. Primary dystonias are classified as pure dystonias, dystonia-plus syndromes or paroxysmal dystonias. Assessment should be performed using a validated rating scale for dystonia. Genetic testing may be performed after establishing the clinical diagnosis. DYT1 testing is recommended for patients with primary dystonia with limb onset before age 30, as well as in those with an affected relative with early onset dystonia. DYT6 testing is recommended in early-onset or familial cases with cranio-cervical dystonia or after exclusion of DYT1. Individuals with early-onset myoclonus should be tested for mutations in the DYT11gene. Gene dosage is required so as to improve the proportion of mutations detected. A levodopa trial is warranted in every patient with early onset dystonia without an alternative diagnosis. In patients with idiopathic dystonia, neurophysiological tests can help with describing the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the disorder. Treatment: Botulinum toxin (BoNT) type A is the first line treatment for primary cranial (excluding oromandibular) or cervical dystonia; it is also effective on writing dystonia. -

Long-Term Follow-Up of Levodopa Responsiveness in Generalized Dystonia

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION Long-term Follow-up of Levodopa Responsiveness in Generalized Dystonia Richard B. Dewey, Jr, MD; Manfred D. Muenter, MD; Asha Kishore, MD; Barry J. Snow, MD Objectives: To assign an accurate diagnosis to pa- toms of dystonia as the drug was withheld. In each case, tients with dystonia based on the presence of sustained worsening of dystonia did not occur until 29 hours or levodopa responsiveness and to determine whether mo- more after levodopa withdrawal, providing evidence for tor fluctuations occur in patients with dystonia who are a response profile similar to the long duration response withheld from levodopa. described in Parkinson disease. No significant changes were seen in the dystonia scores of the 3 patients with Patients and Methods: Patients with generalized dys- idiopathic torsion dystonia who were withheld from le- tonia who responded to treatment in the 1970s with le- vodopa. vodopa/carbidopa were surveyed by phone and then ex- amined during a 3-day levodopa holiday. Functional Conclusions: We suggest that the subjective feeling of imaging with fluorodopa positron emission tomogra- wearing off experienced by our patients with dopa- phy was performed on a subset of patients. responsive dystonia may have been for one of the non– motor effects of levodopa, such as mood elevation. Our Results: In the phone interview, 4 of 7 patients with a data provide objective evidence for the often-repeated as- diagnosis of dopa-responsive dystonia reported the wear- sertion that motor fluctuations (analogous to those in le- ing-off effect a short while (within 4-8 hours) after miss- vodopa-treated patients with Parkinson disease) do not ing a dose of levodopa. -

Botulinum Toxin

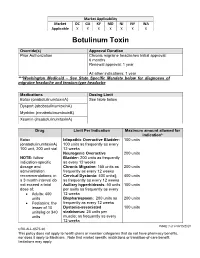

Market Applicability Market DC GA KY MD NJ NY WA Applicable X X X X X X X Botulinum Toxin Override(s) Approval Duration Prior Authorization Chronic migraine headaches Initial approval: 6 months Renewal approval: 1 year All other indications: 1 year ***Washington Medicaid – See State Specific Mandate below for diagnoses of migraine headache and tension-type headache Medications Dosing Limit Botox (onabotulinumtoxinA) See table below Dysport (abobotulinumtoxinA) Myobloc (rimabotulinumtoxinB) Xeomin (incobotulinumtoxinA) Drug Limit Per Indication Maximum amount allowed for indication* Botox Idiopathic Overactive Bladder: 100 units (onabotulinumtoxinA) 100 units as frequently as every 100 unit, 200 unit vial 12 weeks Neurogenic Overactive 200 units NOTE: follow Bladder: 200 units as frequently indication-specific as every 12 weeks dosage and Chronic Migraine: 155 units as 200 units administration frequently as every 12 weeks recommendations; in Cervical Dystonia: 400 units§ 400 units a 3 month interval do as frequently as every 12 weeks not exceed a total Axillary hyperhidrosis: 50 units 100 units dose of: per axilla as frequently as every Adults: 400 12 weeks units Blepharospasm: 200 units as 200 units Pediatrics: the frequently as every 12 weeks lesser of 10 Dystonia-associated 100 units units/kg or 340 strabismus: 25 units per units muscle; as frequently as every 12 weeks PAGE 1 of 9 08/15/2020 CRX-ALL-0575-20 This policy does not apply to health plans or member categories that do not have pharmacy benefits, nor does it apply to Medicare. -

Treatment of Blepharospasm and Oromandibular Dystonia with Botulinum Toxins

toxins Review Treatment of Blepharospasm and Oromandibular Dystonia with Botulinum Toxins Travis J.W. Hassell * and David Charles Department of Neurology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, 1161 21st Avenue South, Suite A-1106 MCN, Nashville, TN 37232, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 29 March 2020; Accepted: 18 April 2020; Published: 22 April 2020 Abstract: Blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia are focal dystonias characterized by involuntary and often patterned, repetitive muscle contractions. There is a long history of medical and surgical therapies, with the current first-line therapy, botulinum neurotoxin (BoNT), becoming standard of care in 1989. This comprehensive review utilized MEDLINE and PubMed and provides an overview of the history of these focal dystonias, BoNT, and the use of toxin to treat them. We present the levels of clinical evidence for each toxin for both, focal dystonias and offer guidance for muscle and site selection as well as dosing. Keywords: blepharospasm; oromandibular dystonia; Meige syndrome; botulinum toxin; OnabotulinumtoxinA; AbobotulinumtoxinA; IncobotulinumtoxinA; RimabotulinumtoxinB; DaxibotulinumtoxinA Key Contribution: Blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia are common focal dystonic disorders. This comprehensive review provides better understanding of the current knowledge base regarding these conditions; the present therapeutic standard of care; and current treatment strategies with botulinum toxin injections. Providing a comprehensive source for this information gives practitioners a guide to improving the quality of their care. 1. Introduction Cranial dystonias are hyperkinetic movement disorders manifested by abnormal, involuntary movements of cranial muscles, characterized by intermittent or sustained muscle contractions. Two of the most common focal cranial dystonias are blepharospasm and oromandibular dystonia (OMD). -

Genetic Types of HSP* Autosomal Dominant

Genetic types of HSP* Autosomal dominant HSP Spastic gait (SPG) locus OMIM# Clinical Syndrome SPG3A 182600 Atlastin Uncomplicated HSP: symptoms usually begin in childhood (and may be non-progressive); symptoms may also begin in adolescence or adulthood and worsen insidiously. Genetic non-penetrance reported. De novo mutation reported presenting as spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. SPG4 182601 Spastin Uncomplicated HSP, symptom onset in infancy through senescence, single most common cause of autosomal dominant HSP (~40%); some subjects have late onset cognitive impairment. SPG6 600363 NIPA1 Uncomplicated HSP: prototypical late-adolescent, early-adult onset, slowly progressive uncomplicated HSP. Rarely complicated by epilepsy or variable peripheral neuropathy. One subject with uncomplicated HSP later died from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. SPG8 603563 KIAA0196 Uncomplicated HSP, adult-onset. (Strumpellin) SPG9A 601162 ALDH18A1 Complicated spastic paraplegia associated with cataracts, gastroesophageal reflux, peripheral neuropathy, variably accompanied by dysarthria, ataxia, cognitive impairment. Onset in adolescence to adulthood (one subject with infantile onset). Subjects from several unrelated families and two “apparently sporadic” subjects reported. SPG10 604187 Kinesin heavy Uncomplicated HSP or complicated by distal muscle atrophy chain (KIF5A) SPG12 604805 Reticulon 2 Uncomplicated HSP (RTN2) SPG13 605280 Chaperonin 60 Uncomplicated HSP: adolescent and adult onset (HSP60) SPG17 270685 BSCL2/seipin Complicated: spastic paraplegia associated -

CNS Critical Periods: Implications for Dystonia and Other Neurodevelopmental Disorders

CNS critical periods: implications for dystonia and other neurodevelopmental disorders Jay Li, … , Samuel S. Pappas, William T. Dauer JCI Insight. 2021;6(4):e142483. https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.142483. Review Critical periods are discrete developmental stages when the nervous system is especially sensitive to stimuli that facilitate circuit maturation. The distinctive landscapes assumed by the developing CNS create analogous periods of susceptibility to pathogenic insults and responsiveness to therapy. Here, we review critical periods in nervous system development and disease, with an emphasis on the neurodevelopmental disorder DYT1 dystonia. We highlight clinical and laboratory observations supporting the existence of a critical period during which the DYT1 mutation is uniquely harmful, and the implications for future therapeutic development. Find the latest version: https://jci.me/142483/pdf REVIEW CNS critical periods: implications for dystonia and other neurodevelopmental disorders Jay Li,1,2 Sumin Kim,2 Samuel S. Pappas,3,4 and William T. Dauer3,4,5 1Medical Scientist Training Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. 2Cellular and Molecular Biology Graduate Program, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. 3Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, 4Department of Neurology, and 5Department of Neuroscience, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, Texas, USA. Critical periods are discrete developmental stages when the nervous system is especially sensitive to stimuli that facilitate circuit maturation. The distinctive landscapes assumed by the developing CNS create analogous periods of susceptibility to pathogenic insults and responsiveness to therapy. Here, we review critical periods in nervous system development and disease, with an emphasis on the neurodevelopmental disorder DYT1 dystonia.