Rediscovering Goethe's Concept of Polarity: a New Direction for Architectural Morphogenesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

402 Great Spires: Skyscrapers of the New Jerusalem Missing the Point? the Death and Afterlife of Great Spires 401

402 Great Spires: Skyscrapers of the New Jerusalem Missing the Point? The Death and Afterlife of Great Spires 401 PART V: SPIRES IN THE POSTMEDIEVAL WORLD Chapter 11: Missing the Point? The Death and Afterlife of Great Spires The post-medieval history of great spires and their reception falls, roughly speaking, into four distinct phases, which might be termed demise, sublimation, revival, and contemplation. By the end of the sixteenth century, virtually all the great spire projects in Europe had ground to a halt, as the artistic, cultural, and religious practices of the Middle Ages gave way to those of the early modern era. Crucial factors in this transformation include the spread of Italianate Renaissance classicism, the related rise of royal and courtly patronage, and the shock of the Reformation and its aftermath. In the period from roughly 1530 to 1800, therefore, the Gothic style was almost entirely forsaken. Significantly, however, church spires retained a certain degree of popularity, especially in countries such as Holland, England, and Germany where churches remained important as monuments of local and communal identity. Spire designers working in this period faced the difficult task of marshaling the classical architectural vocabulary to create striving vertical forms appropriate to this originally Gothic monument type. The Gothic Revival movement of the nineteenth century naturally fostered closer engagement with Gothic traditions of spire design, as the completion of major medieval spire projects like those of Cologne and Ulm attests. The archaeological rigor of these initiatives, however, was not matched by consistent scholarly objectivity, since Romanticism and nationalism played important roles in shaping the nineteenth-century view of the Middle Ages. -

The Walls of the Confessions: Neo-Romanesque Architecture, Nationalism, and Religious Identity in the Kaiserreich by Annah Krieg

The Walls of the Confessions: Neo-Romanesque Architecture, Nationalism, and Religious Identity in the Kaiserreich by Annah Krieg B.A., Lawrence University, 2001 M.A., University of Pittsburgh, 2004 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The School of Art and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2010 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Annah Krieg It was defended on April 2, 2010 and approved by Christopher Drew Armstrong, Director of Architectural Studies and Assistant Professor, History of Art and Architecture Paul Jaskot, Professor, Art History , DePaul University Kirk Savage, Professor and Chair, History of Art and Architecture Terry Smith, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Contemporary Art History and Theory, History of Art and Architecture Dissertation Advisor: Barbara McCloskey, Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture ii The Walls of the Confessions: Neo-Romanesque Architecture, Nationalism, and Religious Identity in the Kaiserreich Annah Krieg, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2010 Scholars traditionally understand neo-Romanesque architecture as a stylistic manifestation of the homogenizing and nationalizing impulse of the Kaiserreich. Images of fortress-like office buildings and public halls with imposing facades of rusticated stone dominate our view of neo-Romanesque architecture from the Kaiserreich (1871-1918). The three religious buildings at the core of this study - Edwin Oppler’s New Synagogue in Breslau (1866-1872), Christoph Hehl’s Catholic Rosary Church in Berlin-Steglitz (1899-1900), and Friedrich Adler’s Protestant Church of the Redeemer in Jerusalem (1893-1898) – offer compelling counter- examples of the ways in which religious groups, especially those that were local minorities, adapted the dominant neo-Romanesque style to their own particular quest towards distinctive assimilation in an increasingly complex, national, modern society. -

National Backgrounds

LIBER Manuscript Librarians Group Manuscript Librarians Group National Backgrounds This document is a compilation of the background information in the national reports of the LIBER Manuscript Librarians Group. The reports have been written by: Alois Haidinger (Austria), Thierry Delcourt (France), Alessandra Sorbello Staub (Germany), Scot McKendrick (Great Britain), Bernard Meehan (Ireland), Francesca Niutta with Simona Cives (Italy), André Bouwman (Netherlands), Maria Wrede (Poland), Olga Sapozhnikova (Russia), Anna Gudayol (Spain), Ingrid Svensson (Sweden). The final editing was performed by André Bouwman and Bernard Meehan (2.11. 2007). Contents: Austria (2-4). — France (5). — Germany (6-9). — Great Britain (10-13). — Ireland (14-16). — Italy (17-24). — Netherlands (25- 28). — Poland (29-30). — Russia (31-33). — Spain (34-38). — Sweden (39-41). National Backgrounds / Survey (2.11.2007) 1 LIBER Manuscript Librarians Group Austria — Backgrounds Alois Haidinger (Austrian Academy of Sciences, Commission of Paleography and Codicology of Medieval Manuscripts in Austria) Contents: Libraries. — Austrian National Library. — Universitätsbibliothek Graz. — Universitätsbibliothek Insbruck. — Universitätsbibliothek Klagenfurt. — Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek, Linz. — Stift Klosterneuburg. — Stift Admont. — Stift Melk. — Stift St. Peter in Salzburg.— Stift Göttweig. — Catalogues, Microfilms. — Cataloguing Projects. Libraries Survey of libraries in Austria holding manuscripts: http://www.ksbm.oeaw.ac.at/_scripts/php/msslib.php The largest public manuscript collections are held by the Austrian National Library, the university libraries of Graz, Innsbruck, Klagenfurt, Salzburg and the Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek Linz. Over and above that, large numbers of manuscripts in Austria are in the possession of still active monasteries. Due to the lack of modern manuscript catalogues for most of the Austrian collections, the total number of medieval manuscripts in Austrian libraries can only be estimated on approximately 20,000. -

The Dream of Erwin Von Steinbach; Art and Religion, Gender and Genius

The Dream of Erwin von Steinbach; Art and religion, gender and genius An essay by Tori Dearborn The Strasbourg Cathedral Designed by Erwin von Steinbach, constructed from 1176-1439 The Medieval Architect and the Gothic Revival Erwin von Steinbach, Architect of the Strasbourg Cathedral 1244 - 1318 Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Moritz von Schwind, Author of On German Architecture His biggest fans Painter of the Dream of Erwin von Steinbach 1749 - 1831 1804 -1871 Schwind, The Dream of Erwin von Steinbach, 1822 The Sanctification of the Arts The 19th century saw a steady decrease in religious belief, spurred by the scientific developments of the Enlightenment. In its place rose the worship of the arts. It was the beginning of “art for art’s sake,” a term aptly coined during the late 19th century. Veit, The Arts Introduced in Germany by Christianity 1834 to 1836 Worship of the Arts How is religious symbolism applied to Art? Hoff after Franz Pforr, Durer and Raphael at the Throne of Art, 1832 Overbeck, Durer and Raphael at the Throne of Art, 1810 The Romantic Nightmare Goya, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, 1797 Gustave Dore, Harpies in the Forest of Suicide The Romantic Motif of Dreaming The Dream as Religious Vision Blake, Jacob’s Dream, 1799-1806 Führich, Dream of St. Bernard as a Child, 1830 The Dream as Artistic Vision The dream as religious revelation soon became the dream as artistic inspiration. Koch, The Dream of Dante Blake, Dreams of the Youthful Poet, John Milton, 1816 The Genius as Pseudo Religious Art Idol “The life of the divine -

Królewski Kościół Katedralny Na Wawelu. W Rocznicę Konsekracji 1364–2014 Wprowadzenie

Tomasz Węcławowicz Królewski kościół katedralny na Wawelu W rocznicę konsekracji 1364–2014 Royal Cathedral Church on Wawel Hill in Krakow Jubilee of the Consecration 1364–2014 Dekoracja zachodniej ściany katedry dobitnie ilustruje powiązanie św. Stanisława z ideą polityczną ostatnich władców z dynastii Piastów. Szczyt wieńczy fi gura św. Stani- sława, poniżej na drzwiach widnieje monogram króla Kazimierza Wielkiego – a między nimi Orzeł, herb Królestwa Polskiego – heraldyczny łącznik spajający dwie personifi kacje religijnej i świeckiej władzy. […] Dlatego krakowska katedra jest w każdym znaczeniu tego słowa „kościołem królewskim” – a przy tym jedną z najwcześniejszych takich realizacji w Europie Środkowej. Paul Crossley, Gothic Architecture in the Reign of Kazimir the Great, Kraków 1985 [Th e] demonstration of the link between St Stanislaw and the political ideology of the last Piast King is provided by the decoration of the west front of the cathedral. Above, in the gable is the fi gure of St Stanislaw; below, on the doors, is the pronounced signature of Kazimir the Great; and between them, as a heraldic link between these two personifi ca- tions of the religious and secular authority, is the Polish eagle, the arms of Poland […] In every sense of the word, therefore, Krakow cathedral is – a Königskirche. It is moreover one of the earliest of its kind in Central Europe. Paul Crossley, Gothic Architecture in the Reign of Kazimir the Great, Krakow 1985 Tomasz Węcławowicz Królewski kościół katedralny na Wawelu W rocznicę konsekracji 1364–2014 Royal Cathedral Church on Wawel Hill in Krakow Jubilee of the Consecration 1364–2014 Kraków 2014 UNIWERSYTET PAPIESKI JANA PAWŁA II WYDZIAŁ HISTORII I DZIEDZICTWA KULTUROWEGO PONTIFICAL UNIVERSITY OF JOHN PAUL II FACULTY OF HISTORY AND CULTURAL HERITAGE KRAKOWSKA AKADEMIA IM. -

Chapter 5: Innovations in the Rhineland

110 Great Spires: Skyscrapers of the New Jerusalem PART III: PRIDE, PIETY, AND COMMUNITY: THE GOLDEN AGE OF SPIRE CONSTRUCTION IN THE HOLY ROMAN EMPIRE Chapter 5: Innovations in the Rhineland It was in the Rhineland in the decades around 1300 that the design of great spires finally began to catch up with the dramatic strides made over the previous century in other facets of Gothic architectural production, especially in France. In Strasbourg, Cologne, and Freiburg, in particular, up-to-date French Rayonnant ideas about the skeletalization of form were decisively brought to bear for the first time on the problem of spire design. One major consequence of this process was the invention of the openwork spire type, which would subsequently enjoy great popularity, especially in the German-speaking world. This first flourishing of Rhenish spire design paved the way for the emergence of the Holy Roman Empire as the superpower in spire construction in the late Gothic era. The innovative spire projects of the Rhineland thus occupy a pivotal place in the overall history of the Gothic great spire phenomenon, at the geographical boundary between the French and German spheres, and at the chronological boundary between the periods often identified as the High and Late Middle Ages.1 The flowering of Rhenish spire design coincided with the establishment of drawing as a crucial tool of architectural planning and formal invention. With the exception of Villard de Honnecourt's notebook, the vast majority of the earliest surviving Gothic architectural drawings were associated with the Rhenish spire and facade projects of Strasbourg, Cologne, and Freiburg. -

Part Three: Development of Conservation Theories

J. Jokilehto, A History of Architectural Conservation D. Phil Thesis, University of York, 1986 Part Three: Development of Conservation Theories Page 230 J. Jokilehto Chapter Thirteen Restoration of Classical Monuments 13.1 Principles created during the French Concorde, symbolized this attitude. Consequently, Revolution it was not until 1830s before mediaeval structures had gained a lasting appreciation and a more firmly The French Revolution became the moment established policy for their conservation. of synthesis to the various developments in the appreciation and conservation of cultural heritage. 13.2 Restoration of Classical Monuments Vandalism and destruction of historic monuments (concepts defined during the revolution) gave a in the Papal State ‘drastic contribution’ toward a new understanding In Italy, the home country of classical antiquity, where of the documentary, scientific and artistic values legislation for the protection of ancient monuments contained in this heritage, whcih so far had been had already been developed since the Renaissance closed away and forbidden to most people. Now for (or infact from the times of antiquity!), and where the the first time, ordinary citizens had the opportunity to position of a chief Conservator existed since the times come in contact with these unknown works of art. The of Raphael, patriotic expressions had often justified lessons of the past had to be learnt from these objects acts of preservation. During the revolutionary years, in order to keep France in the leading position even when the French troops occupied Italian states, and in the world of economy and sciences. It was also plundered or carried away major works of art, these conceived that this heritage had to be preserved in situ feelings were again reinforced. -

Strasbourg Guide

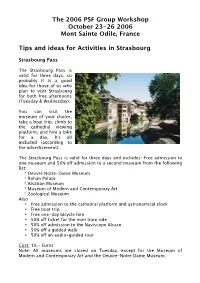

The 2006 PSF Group Workshop October 23-26 2006 Mont Sainte Odile, France Tips and ideas for Activities in Strasbourg Strasbourg Pass The Strasbourg Pass is valid for three days, so probably it is a good idea for those of us who plan to visit Strasbourg for both free afternoons (Tuesday & Wednesday). You can visit the museum of your choice, take a boat trip, climb to the cathedral viewing platform, and hire a bike for a day. It's all included (according to the advertisement). The Strasbourg Pass is valid for three days and includes: Free admission to one museum and 50% off admission to a second museum from the following list: * Oeuvre Notre-Dame Museum * Rohan Palace * Alsatian Museum * Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art * Zoological Museum Also • Free admission to the cathedral platform and astronomical clock • Free boat trip • Free one-day bicycle hire • 50% off ticket for the mini tram ride • 50% off admission to the Naviscope Alsace • 50% off a guided walk • 50% off an audio-guided tour Cost: 10,- Euros Note: All museums are closed on Tuesday, except for the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art and the Oeuvre-Notre Dame Museum. Places to visit in Strasbourg Cruise on the Ill River and city-tour in a mini-tram Visit the city along the river in a guided cruise, or in a guided tour by mini- tram. More in “Strasburg in your pocket” PDF brochure. Notre-Dame Cathedral The Strasbourg Cathedral (Notre Dame) is built of red sandstone, principally in Gothic style, with some Romanesque features. -

POETRY and the ART of BUILDING Goethe's Morphology As Applied to Architecture

POETRY AND THE ART OF BUILDING Goethe's Morphology as applied to Architecture A Thesis Presented To The Faculty of the Division of Graduate Studies by Daniel F. Hellmuth In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Architecture in the College of Architecture Georgia Institute of Technology December 1986 Approved: y Dr. John Ternpler.JChairman —— u-t Prof. M. Frascan Prof. Arch. Bruno Zevi Date Approved by Chairman: I ~~ 3 — £ £ Original Page Numbering Retained. Poetry and the Art of Building - Goethe's Morphology as applied to Architecture . • • • • - Table of Contents Page Dedication ii Acknowledgements iii Notes on Translations v Self-Description, J. W. Von Goethe vi INTRODUCTION 1 I. The Formative Years: Classicism versus Romanticism 33 II. Awakening of Genius: The Shock of Strasbourg 43 III. The Weimar Park: Poetry and Landscape 60 IV. A Return to the Source: The Italian Journey or Goethe in Arcadia 86 V. Towards a New Theory of Architecture 142 VI. Application of Principles: 'The Weimar School' 175 VII. Maturity and Reflection 240 CONCLUSION 302 APPENDIX A. Sources of Illustrations I B. Goethe's Poem: "The Metamorphosis of Plants" XVI C. Goethe's Fragment "Nature: Aphoristic" XVLTI D. Chronology — Johann Wolfgang von Goethe XX E. Selected Bibliography XXIII Cover Illustration: Goethe in the Countryside, Silk Screen: Andy Warhol, 1981. Dedication This thesis is dedicated to Alane Ingrid Clay for her companionship and laughter that made much of this work such a pleasure. -ii- Acknowledgements Where do I start?! Considering that work first began on this over five years ago, there are many people I'm indebted to. -

The Legacy of German Neoclassicism and Biedermeier: Behrens, Tessenow, Loos, and Mies

The Legacy of German Neoclassicism and Biedermeier: Behrens, Tessenow, Loos, and Mies Stanford Anderson Assemblage, No. 15. (Aug., 1991), pp. 62-87. Stable URL: http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0889-3012%28199108%290%3A15%3C62%3ATLOGNA%3E2.0.CO%3B2-A Assemblage is currently published by The MIT Press. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/about/terms.html. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/journals/mitpress.html. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. The JSTOR Archive is a trusted digital repository providing for long-term preservation and access to leading academic journals and scholarly literature from around the world. The Archive is supported by libraries, scholarly societies, publishers, and foundations. It is an initiative of JSTOR, a not-for-profit organization with a mission to help the scholarly community take advantage of advances in technology. For more information regarding JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Wed Aug 8 14:37:50 2007 Stanford Anderson The Legacy of German Neoclassicism and Biedermeier: Behrens, Tessenow, Loos, and Mies Stanford Anderson is Head of the Depart- Around 1900 cultural critics and producers alike com- ment of Architecture at the Massachusetts monly willed to reestablish a harmoniously unified society, Institute of Technology and is Professor whether by innovation or revival.