Open Research Online Oro.Open.Ac.Uk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Corporate Investment Wing Sustainable Finance Division Corporate Social Responsibility Department Head Office, Dhaka

Islami Bank Bangladesh Limited Corporate Investment Wing Sustainable Finance Division Corporate Social Responsibility Department Head Office, Dhaka. Sub: Result of IBBL Scholarship Program, HSC Level-2019 Following 1500(Male-754, Female-746) students mentioned below have been selected finally for IBBL Scholarship program, HSC Level -2019. Sl. No. Name of Branch Beneficiary ID Student's Name Father's Name Mother's Name 1 Agrabad Branch 8880202516103 Halimatus Sadia Didarul Alam Jesmin Akter 2 Agrabad Branch 8880202516305 Imam Hossain Mahbubul Hoque Aleya Begum 3 Agrabad Branch 8880202508003 Md Mahmudul Hasan Al Qafi Mohammad Mujibur Rahman Shaheda Akter 4 Agrabad Branch 8880202516204 Proma Mallik Gopal Mallik Archana Mallik 5 Alamdanga Branch 8880202313016 Mst. Husniara Rupa Md. Habibur Rahman Mst. Nilufa Yeasmin 6 Alamdanga Branch 8880202338307 Sharmin Jahan Shormi Md. Abdul Khaleque Israt Jahan 7 Alanga SME/Krishi Branch 8880202386310 Tammim Khan Mim Md. Gofur Khan Mst. Hamida Khanom 8 Amberkhana Branch 8880202314017 Fahmida Akter Nitu Babul Islam Najma Begum 9 Amberkhana Branch 8880202402015 Fatema Akter Abdul Kadir Peyara Begum 10 Amberkhana Branch 8880202252201 Mahbubur Rahman Md. Juned Ahmed Mst. Shomurta Begum 11 Amberkhana Branch 8880202208505 Md. Al-Amin Moin Uddin Rafia Begum 12 Amberkhana Branch 8880202457814 Md. Ismail Hossen Md. Rasedul Jaman Ismotara Begum 13 Amberkhana Branch 8880202413118 Mst. Shima Akter Tofazzul Islam Nazma Begum 14 Amberkhana Branch 8880202378513 Tania Akther Muffajal Hossen Kamrun Nahar 15 Amberkhana Branch 8880202300618 Tanim Islam Tanni Shahidul Islam Shibli Islam 16 Amberkhana Branch 8880202234504 Tanjir Hasan Abdul Malik Rahena Begum 17 Anderkilla Branch 8880202497414 Arpita Barua Alak Barua Tapasi Barua 18 Anderkilla Branch 8880202269108 Sakibur Rahman Mohammad Younus Ruby Akther 19 Anwara Branch 8880202320115 Jinat Arabi Mohammad Fajlul Azim Raihan Akter 20 Anwara Branch 8880202263607 Mizanur Rahman Abdul Khalaque Monwara Begum 21 Anwara Branch 8880202181101 Mohammad Arif Uddin Mohammad Shofi Fatema Begum Sl. -

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No

Name of the Centre : DAV Bachra No. Of Students : 474 SL. No. Roll No. Name of the Student Father's Name Mother's Name 1 19002 AJAY ORAON NIRMAL ORAON PATI DEVI 2 19003 PUJA KUMARI BINOD PARSAD SAHU SUNITA DEVI 3 19004 JYOTSANA KUMARI BINOD KUMAR NAMITA DEVI 4 19005 GAZAL SRIVASTVA BABY SANTOSH KUMAR SRIVASTAVA ASHA SRIVASTVA 5 19006 ANURADHA KUMARI PAPPU KUMAR SAH SANGEETA DEVI 6 19007 SUPRIYA KUMARI DINESH PARSAD GEETA DEVI 7 19008 SUPRIYA KUMARI RANJIT SHINGH KIRAN DEVI 8 19009 JYOTI KUMARI SHANKAR DUBEY RIMA DEVI 9 19010 NIDHI KUMARI PREM KUMAR SAW BABY DEVI 10 19011 SIMA KUMARI PARMOD KUMAR GUPTA SANGEETA DEVI 11 19012 SHREYA SRIVASTAV PRADEEP SHRIVASTAV ANIMA DEVI 12 19013 PIYUSH KUMAR DHANANJAY MEHTA SANGEETA DEVI 13 19014 ANUJ KUMAR UPENDRA VISHWAKARMA SHIMLA DEVI 14 19015 MILAN KUMAR SATYENDRA PRASAD YADAV SHEELA DEVI 15 19016 ABHISHEK KUMAR GUPTA SANT KUMAR GUPTA RINA DEVI 16 19017 PANKAJ KUMAR MUKESH KUMAR SUNITA DEVI 17 19018 AMAN KUMAR LATE. HARISHAKAR SHARMA RINKI KUMARI 18 19019 ATUL RAJ RAJESH KUMAR SATYA RUPA DEVI 19 19020 HARSH KUMAR SHAILENDRA KR. TIWARY SNEHLATA DEVI 20 19021 MUNNA THAKUR HIRA THAKUR BAIJANTI DEVI 21 19022 MD.FARID ANSARI JARAD HUSSAIN ANSARI HUSNE ARA 22 19023 MD. JILANI ANSARI MD.TAUFIQUE ANSARI FARZANA BIBI 23 19024 RISHIKESH KUNAL DAMODAR CHODHARY KAMLA DEVI 24 19025 VISHAL KR. DUBEY RAJEEV KUMAR DUBEY KIRAN DEVI 25 19026 AYUSH RANJAN ANUJ KUMAR DWIVEDI ANJU DWIVEDI 26 19027 AMARTYA PANDEY SATISH KUMAR PANDEY REENA DEVI 27 19028 SHIWANI CHOUHAN JAYPAL SINGH MAMTA DEVI 28 19029 SANDEEP KUMAR MEHTA -

Subject Name User Id Guardian's Name BENGALI AYANTIKA SOME VUDDE2010076 ALOKE KUMAR SOME BENGALI ZESMINA KHATUN VUDDE2010079

Directorate of Distance Education, Vidyasagar University Part - I 2020-2021 Student List Subject Name User Id Guardian's Name BENGALI AYANTIKA SOME VUDDE2010076 ALOKE KUMAR SOME BENGALI ZESMINA KHATUN VUDDE2010079 ATAUR RAHAMAN KHAN BENGALI MOU SHOW VUDDE2010081 GANESH SHOW BENGALI DEBJANI CHAKRABORTY VUDDE2010162 GOUR CHAKRABORTY BENGALI SOURAV GHOSH VUDDE2010165 SUSANTA GHOSH BENGALI TAPAS KUNDU VUDDE2010186 SUKUMAR SUNDAR KUNDU BENGALI FALGUNI SAMANTA VUDDE2010191 PRIMAL SAMANTA BENGALI RIMPA CHATTERJEE VUDDE2010310 TIMIR CHATTERJEE BENGALI JHUNU PRADHAN VUDDE2010360 ASHOKE KUMAR PRADHAN BENGALI SUTAPA CHATTERJEE VUDDE2010441 DEBDAS CHATTERJEE BENGALI PARI MAHATO VUDDE2010450 SUSEN MAHATO BENGALI ARITI ADHIKARY VUDDE2010472 ARUN KUMAR ADHIKARY BENGALI SUSMITA DULEY VUDDE2010489 NIMAI KUMAR DULEY BENGALI SANJOY MONDAL VUDDE2010498 PRAHLAD MONDAL BENGALI SAMARESH SAHOO VUDDE2010659 SANAT SAHOO BENGALI SUSMITA DAS VUDDE2010661 SHANTIPADA DAS BENGALI PALLABI BHOWMICK VUDDE2010700 SUNIL BHOWMICK BENGALI RUPASHREE MAJI VUDDE2010758 AJIT KUMAR MAJI BENGALI SUVADIP DASH VUDDE2010815 DEBASISH DASH BENGALI PRIYANKA DE VUDDE2010846 BALARAM DE BENGALI ANANYA PATTANAYAK VUDDE2010911 ASOK PATTANAYAK BENGALI TUSI BHOWMIK VUDDE2010917 TAPAS BHOWMIK BENGALI JUI NASKAR VUDDE2010931 DEBESH NASKAR BENGALI PRALAY PAIN VUDDE2010960 TAPAN KUMAR PAIN BENGALI KOUSHIK SANTRA VUDDE2010962 TAPAS SANTRA BENGALI MEDHA BHATTACHARYA VUDDE2010965 DEBASISH BHATTACHARYA BENGALI SWARUPA DAS VUDDE2011048 KOLLOL KUMAR DAS BENGALI SOUMIKA DHARA VUDDE2011062 SUBRATA KUMAR -

A Brief History of Music in Bangladeshi Cinema Before Liberation (1956-1970)

Vol-6 Issue-3 2020 IJARIIE-ISSN(O)-2395-4396 A Brief History of Music in Bangladeshi Cinema before liberation (1956-1970). Ruksana Karim Lecturer, Dept. of Music, Jagannath University, Dhaka, Bangladesh. Former research fellow, 2015-16 & 2018-19 Bangladesh Film Archive. Abstract This study describes the beginning of musical journey of Bangladeshi cinema. The 49 years old country ‘Bangladesh’ has a beautiful history of cinema and music (near about 122 years old). But the journey was not as easy as present when Bangladesh (previous East Pakistan) was a part of Pakistan. This paper is a complete narration of musical perspective in Bangladeshi cinema and introduces authentic Bangladeshi culture. The history of Bangladeshi cinema is very much related with Indo-Pak sub continental cinema history. From another aspect, this study discusses the positive sides, all ups and downs of the beginning period of Bangladeshi cinema music. The methodology of this study is purely based on historical analysis and description that includes quite observation, literature reviews and interviews. Music in Bangladeshi cinema is strongly connected to the roots of its culture and this chapter really needs a quality research to go forward. From another view, this study introduces a good number of film makers and music directors of Bangladesh who had a lot of art work to make the history, classifies the film song in different categories and describes how the socio-economic condition presents through music in cinemas? It seems like a mirror, which is only the reflection, their life, culture and Bengali nationality. To forward this glory to the future generation and other nations, there is no alternative of describing the fundamental history as this study is doing. -

Bsc-List-2021.Pdf

Serial NO USER ID APPLICANT NAME FATHER NAME MOTHER NAME SSC ROLL SSC GPA HSC ROLL HSC GPA STATUS PROGRAM 1 PROGRAM 2 1 BWLBIAR ABDUL KARIM ABDUL JALIL ASRAFUN NAHAR PANNA 151941 5.00 135304 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 2 BCKZIWW MD. SADEKUZZAMAN NISHAT MD. NURUL ISLAM MOST. SAFURA BEGUM 197415 5.00 133445 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 3 BOZTVVP SYED JISAN KABIR SYED HUMAUN KABIR MST. SOHELA PARVIN 122848 4.78 117454 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 4 BTOYUFQ JUBAER AL- AMIN EMON MD. NURUL AMIN KHADIZA BEGUM 112310 5.00 134312 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 5 BQEEWWA KHONDOKER AMIMUL AHASAN KHONDOKER SHAHJAHAN HAIDER MOHUA AKTER RUMI 113572 5.00 126831 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 6 BAXLYGI NAZYA MUSTAFIZ MD. HASAN MUSTAFIZ MST. JEBUN NAHAR 132195 5.00 115611 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 7 BAHFMZO NOOR-E-TAOHEED ALAMIN NOOR-E-KHAJA ALAMIN SABRINA QUADIR 106558 4.94 144405 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 8 BKALAXP FAHMIDA YASMIN NISHI MD. RAFIQUL ISLAM MOSD. ROWSHAN ARA 116688 5.00 108880 4.50 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 9 BBQMHFL SAYERIN NURESHA ORTHI MD. JAHANGIR ALAM SABINA YASMIN 229105 5.00 120540 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 10 BSGBVMD AL IMRAN JAHID HASAN MD. DULAL UDDIN MOST. ZOLEKHA BEGUM 181532 5.00 607569 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 11 BYXRDVN TITHY RANI DAS MANILAL DAS RADHA RANI DAS 108244 5.00 105730 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 12 BOXPDSY MD. AWAL HADI MD. A. HAMID MST. ANJUARA BEGUM 134159 4.89 102828 5.00 ELIGIBLE Aerospace Avionics 13 BJNCFYD NOSHIN NAWAR MOHAMMAD SHAHJAHAN FARZANA MAINUDDIN 116353 5.00 100538 5.00 ELIGIBLE Avionics Aerospace 14 BAXBRUP MD RAFIUL ISLAM MD AMINUL ISLAM MST. -

Temporary List for XI Class Registration Information (Session: 2020-21) Sunamganj Govt

10/8/2020 XICA 2020: College Receive Admission Temporary List for XI Class Registration Information (Session: 2020-21) Sunamganj Govt. College (130051) Shift : Day Version : Bangla Group : Humanities Pass Year Applicant's Name Section Roll No Father's Name Gender Class Opt Board Student eSIF Mother's Name DoB Roll Subjects Sub RegNo Photo Signature 2020 SAZIM MIA A 101,102,107,108,275,304,305, 109 374562 1 JOYNAL MIA M 1001 121,122,269,270,109,110 110 SYLHET NAZMA BEGUM 1716596176 2020 MD. TUFAYEL AHMED A 101,102,107,108,275,304,305, 121 372482 2 MD. SAFIQUL ISLAM M 1002 269,270,109,110,121,122 122 SYLHET MST. JAHERA BEGUM 1716593856 MST. IFRAT JAKIA PEULY 2020 MD. SHOHIBUR A 101,102,107,108,275,269,270, 304 380135 3 F RAHMAN 1003 109,110,121,122,304,305 305 SYLHET MST. KOLIMA 1716606994 KHATUN SABRINA NASRIN 2020 RUNA A 101,102,107,108,275,304,305, 121 121269 4 SHEAK MD BABUL F 1004 269,270,109,110,121,122 122 SYLHET MIA 1716610838 REHENA BEGUM TONIMA SHARMIN 2020 SUMA A 101,102,107,108,275,304,305, 121 119194 5 F SAFIQUE MAMUN 1005 269,270,109,110,121,122 122 SYLHET NAJMA AKTER 1716589168 2020 LIZA SARKER A 101,102,107,108,275,304,305, 121 381702 6 JUDHISTHIR SARKER F 1006 109,110,269,270,121,122 122 SYLHET LOLITA SARKER 1716609320 2020 FAHMIDA AKTER A 101,102,107,108,275,109,110, 121 365620 7 SHOFIK MIA F 1007 269,270,304,305,121,122 122 SYLHET NASIMA BEGUM 1716582208 2020 AMIT HASAN A 101,102,107,108,275,109,110, 121 118595 8 MONSUR ALI M 1008 269,270,304,305,121,122 122 SYLHET KORUNA BEGUM 1716581069 2020 TUFAYEL AHMED A 101,102,107,108,275,304,305, 109 374549 9 MD. -

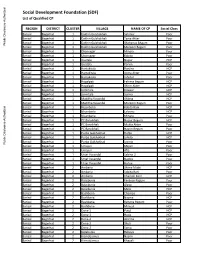

List of Qualified CP

Social Development Foundation (SDF) List of Qualified CP REGION DISTRICT CLUSTER VILLAGE NAME OF CP Social Class Barisal Bagerhat 1 Dakhin Gulshakhali Sahinur Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Dakhin Gulshakhali Tania Akter Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Dakhin Gulshakhali Shahanus BAgum Poor Public Disclosure Authorized Barisal Bagerhat 1 Dakhin Gulshakhali Moreom Bagum Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Dhansagar Minara Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Dhansagar Kabita Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Guatala Nupur HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Guatala Parvin Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Hartakitala Ranjina HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Hartakitala Asma Akter Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Hartakitala Jahidul Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Hogalpati Fahima Begum HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Hogalpati Shirin Akter HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Jamirtala Kawsar HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Jamirtala Surma HCP Public Disclosure Authorized Barisal Bagerhat 1 Maddha Vasandal Aklima HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Maddha Vasandal Moreom Bagum Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Nisanbaria Kabita Rani HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Nisanbaria Lalvanu HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Nisanbaria Minara Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 PC Baroikhali Nupur Begum HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 PC Baroikhali Mukta Akter Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 PC Baroikhali Nasrin Begum Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Purba Gulshakhali Hafija HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Purba Gulshakhali Jahida HCP Barisal Bagerhat 1 Purba Gulshakhali Jasmin Poor Public Disclosure Authorized Barisal Bagerhat 1 Umajuri Mejan Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Umajuri Afia Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Uttar Vasandal Sabina-2 Poor Barisal Bagerhat 1 Uttar Vasandal -

List of Eligible Candidates for Written Test

List of Eligible Candidates for Written Test Faculty/Program: Faculty of Security & Strategic Studies Session: Jan - Jun 2020 SL# Name Father Name Quota Roll No 1 017*****633 MAGHARUL ISLAM Freedom Fighter 1220003115 Military, Senate and 2 A A M NASIM UDDIN MD. ZAMIR UDDIN 1220009835 Syndicate Members 3 A H M MAHAMUDUN NABI MD. HAMIDUL HOQUE Not Applicable 1220005088 Military, Senate and 4 A N EBNUL FAHIM SHIRSO TOFAIL AHAMMED 1220008054 Syndicate Members Military, Senate and 5 A N M JUBAIR TANVIR MD. JAINAL ABEDIN 1220001242 Syndicate Members Military, Senate and 6 A S M NAIMUR RAHMAN MD MOSHIUR RAHMAN 1220008152 Syndicate Members 7 A S M RUBAYET HASAN MOHAMMED KAMRUL HASAN Not Applicable 1220006685 8 A. B. M. FAHIM HASAN TANZIN MD. ABDUL GANI Not Applicable 1220006391 9 A. B. M. MASBAH UDDIN MOHAMMAD MONIRUDDIN Not Applicable 1220002174 10 A. K. M. ABID HASAN MD. ZAHURUL ISLAM Not Applicable 1220000043 11 A. K. M. NAHYAN ISLAM A. K. M. NURUL ISLAM Not Applicable 1220000345 A. K. M. TANJIM RAIYAN 12 A. K. M. SHAFIQUL ISLAM Not Applicable 1220004161 SHAFIN 13 A. N. M. MUHSIN A.U.M IDRISH Not Applicable 1220004949 Military, Senate and 14 A. N. M. ROBIN MD. FARUQUE HOSSAIN 1220002633 Syndicate Members 15 A. S. M RAKIB SAZZAD MD. GOLAM RABBANI Not Applicable 1220006408 16 A. S. M. AMIR HAMZA EFTY A. S. M. AKBOR HOSSAIN Not Applicable 1220005034 A. S. M. EFTEKHAR AHMED 17 S. M. MATIUR RAHMAN Not Applicable 1220007212 MITUL A. S. M. SHAIKOT RAYHAN 18 M. A. MAZID Not Applicable 1220002099 SHAWON 19 A.B.M ISHMAM BHUIYAN AHASAN ULLAH BHUIYAN Not Applicable 1220003984 20 A.B.M MAINUDDIN FAHAD A.B.M MESBAHUDDIN Not Applicable 1220003027 A.B.M. -

Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey 2010

Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey 2010 Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey 2010 National Institute of Population Research and Training (NIPORT) MEASURE Evaluation, UNC-CH, USA icddr,b Funded by: Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh US Agency for International Development (USAID), Bangladesh Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID) United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Bangladesh December 2012 MEASURE Evaluation is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) through cooperative agree- ment GPO-A-00-08-00003-00 and is implemented by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in partnership with Futures Group, ICF International, John Snow, Inc., Management Sciences for Health, and Tulane University. The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the U.S. government. TR-12-87 (December 2012). Data collection and data processing agencies: Associates for Community and Population Research (ACPR) 3/10 Block A, Lalmatia, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Mitra and Associates 2/17 Iqbal Road, Mohammadpur, Dhaka-1207, Bangladesh Special acknowledgement: Dr. Kanta Jamil, Monitoring and Evaluation Advisor, Office of Population, Health, Nutrition and Education, USAID, Bangladesh for technical assistance at all steps of survey implementation, data analysis, and report generation. Cover Photo: Courtesy of Photoshare SNL, Save the Children (USA) The 2010 Bangladesh Maternal Mortality and Health Care Survey is undertaken under the Line Director (Train- ing Research and Development) of the Health, Nutrition and Population Sector Program (HNPSP). The survey is funded by the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, USAID Bangladesh, AusAID, and UNFPA. -

Threads of Everyday Violence: Childhood in an Urdu-Speaking Bihari Camp in Bangladesh

Open Research Online The Open University’s repository of research publications and other research outputs Threads Of Everyday Violence: Childhood In An Urdu-Speaking Bihari Camp In Bangladesh Thesis How to cite: Afroze, Jiniya (2019). Threads Of Everyday Violence: Childhood In An Urdu-Speaking Bihari Camp In Bangladesh. PhD thesis The Open University. For guidance on citations see FAQs. c 2019 The Author https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Version: Version of Record Link(s) to article on publisher’s website: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21954/ou.ro.000107b1 Copyright and Moral Rights for the articles on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. For more information on Open Research Online’s data policy on reuse of materials please consult the policies page. oro.open.ac.uk Threads of everyday violence: Childhood in an Urdu-speaking Bihari camp in Bangladesh Jiniya Afroze A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Childhood Studies Faculty of Wellbeing, Education and Language Studies The Open University May 2019 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my original work and any references are duly acknowledged. The publication that came out of this work: Afroze, J. (2019) ‘Realising childhood in an Urdu-speaking Bihari community in Bangladesh’, in von Benzon, N. and Wilkinson, C. (eds) Intersectionality and Difference in Childhood and Youth: Global Perspectives. London: Routledge, pp. 158-172. 2 Abstract This thesis explores children’s everyday experiences in an Urdu-speaking Bihari camp in Dhaka, Bangladesh. As members of the Bihari community, children and adults living in the camp are historically, ethnically, linguistically, and structurally marginalised. -

Sylhet-Board-Results.Pdf

BOARD OF INTERMEDIATE AND SECONDARY EDUCATION SYLHET JUNIOR SCHOOL CERTIFICATE EXAMINATION, 2017 SCHOLARSHIP (According to Roll No) ZILLA : SYLHET , UPAZILLA : BALAGANJ TALENT POOL STIPEND LIST SL NO NAME OF THE CENTRE ROLL NO NAME NAME OF THE INSTITUTION 1 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515445 MAHBUBA BEGUM MITA TOYRUNNESA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL, BALA GANJ 2 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 516331 MD. NAHID AHMOD KALIGONJ M. ELIAS ALI HIGH SCHOOL GENERAL STIPEND LIST SL NO NAME OF THE CENTRE ROLL NO NAME NAME OF THE INSTITUTION 1 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515446 SAMIRA AKTAR SHAMMI TOYRUNNESA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL, BALA GANJ 2 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515448 ROKAYA AKTER SINTHEYA TOYRUNNESA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL, BALA GANJ 3 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515449 SADIA AKTAR RIPA TOYRUNNESA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL, BALA GANJ 4 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515516 MD. NAZMUS SAKIB BALAGANJ D. N. HIGH SCHOOL, BALAGANJ 5 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515517 ARGHYO PAUL BALAGANJ D. N. HIGH SCHOOL, BALAGANJ 6 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515518 RUHED HASAN MAHEDI BALAGANJ D. N. HIGH SCHOOL, BALAGANJ 7 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515639 SALMA AKTHER BALAGANJ D. N. HIGH SCHOOL, BALAGANJ 8 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515640 SHEIKH TAHMINA AKTHER LUPA BALAGANJ D. N. HIGH SCHOOL, BALAGANJ 9 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515641 NABAMITA CHAKROBORTY BALAGANJ D. N. HIGH SCHOOL, BALAGANJ BOALJUR BAZAR HIGH SCHOOL, BOALJUR 10 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515753 SHEIKH RASEL AHMED BAZAR BOALJUR BAZAR HIGH SCHOOL, BOALJUR 11 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515804 MUST. SAMIA AKTHER BAZAR BOALJUR BAZAR HIGH SCHOOL, BOALJUR 12 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515805 SHAMMI AKTHER BAZAR BOALJUR BAZAR HIGH SCHOOL, BOALJUR 13 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515807 SHUCHANDA DAS THULI BAZAR 3 of 144 SL NO NAME OF THE CENTRE ROLL NO NAME NAME OF THE INSTITUTION 14 111 - BALAGANJ - 1 515967 SHEIKH SAIKAT HUSSAIN MUSLIMABAD IDEAL HIGH SCHOOL.