Opening up to Contemporary Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Ethics of Democratic Deceit

This is a repository copy of The Ethics of Democratic Deceit. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/83254/ Article: Edyvane, D orcid.org/0000-0003-2169-4171 (2015) The Ethics of Democratic Deceit. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 32 (3). pp. 310-325. ISSN 0264-3758 https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12100 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ The Ethics of Democratic Deceit Derek Edyvane Abstract Deception presents a distinctive ethical problem for democratic politicians. This is because there seem in certain situations to be compelling democratic reasons for politicians both to deceive and not to deceive the public. Some philosophers have sought to negotiate this tension by appeal to moral principle, but such efforts may misrepresent the felt ambivalence surrounding dilemmas of public office. A different approach appeals to the moral character of politicians, and to the variety of forms of manipulative communication at their disposal. -

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed up 311 Down

112 It's Over Now 112 Only You 311 All Mixed Up 311 Down 702 Where My Girls At 911 How Do You Want Me To Love You 911 Little Bit More, A 911 More Than A Woman 911 Party People (Friday Night) 911 Private Number 10,000 Maniacs More Than This 10,000 Maniacs These Are The Days 10CC Donna 10CC Dreadlock Holiday 10CC I'm Mandy 10CC I'm Not In Love 10CC Rubber Bullets 10CC Things We Do For Love, The 10CC Wall Street Shuffle 112 & Ludacris Hot & Wet 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says 2 Evisa Oh La La La 2 Pac California Love 2 Pac Thugz Mansion 2 Unlimited No Limits 20 Fingers Short Dick Man 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls 3 Doors Down Duck & Run 3 Doors Down Here Without You 3 Doors Down Its not my time 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3 Doors Down Loser 3 Doors Down Road I'm On, The 3 Doors Down When I'm Gone 38 Special If I'd Been The One 38 Special Second Chance 3LW I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) 3LW No More 3LW No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) 3LW Playas Gon' Play 3rd Strike Redemption 3SL Take It Easy 3T Anything 3T Tease Me 3T & Michael Jackson Why 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Stairsteps Ooh Child 50 Cent Disco Inferno 50 Cent If I Can't 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent P.I.M.P. (Radio Version) 50 Cent Wanksta 50 Cent & Eminem Patiently Waiting 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 21 Questions 5th Dimension Aquarius_Let the sunshine inB 5th Dimension One less Bell to answer 5th Dimension Stoned Soul Picnic 5th Dimension Up Up & Away 5th Dimension Wedding Blue Bells 5th Dimension, The Last Night I Didn't Get To Sleep At All 69 Boys Tootsie Roll 8 Stops 7 Question -

Gender and Sexuality in the Picture of Dorian Gray and Dorian Gray

Gender and Sexuality in The Picture of Dorian Gray and Dorian Gray BA Thesis English Language and Culture Anouska Kersten s4131835 15-08-2014 Supervisor: Dr. D. Kersten Radboud University Kersten s4131835/1 ENGELSE TAAL EN CULTUUR Teacher who will receive this document: D. Kersten Title of document: Gender and Sexuality in The Picture of Dorian Gray and Dorian Gray Name of course: Bachelor Thesis Date of submission: 15-8-2014 The work submitted here is the sole responsibility of the undersigned, who has neither committed plagiarism nor colluded in its production. Signed akersten Name of student: Anouska Kersten Student number: s4131835 Kersten s4131835/2 Abstract In this thesis the novel The Picture of Dorian Gray, written by Oscar Wilde, and the film Dorian Gray (2009), directed by Oliver Parker, are analysed. This thesis aims to provide an answer to the question on how the story of The Picture of Dorian Gray has changed through the influence of the pornofication of the media on the film adaptation Dorian Gray in terms of sexuality and gender. Through the analysis of characters, events, and literary and cinematographic techniques from a gender and sexuality point of view, it has become evident that although The Picture of Dorian Gray adheres to Victorian gender roles and ideas on sexuality, the pornofication of the media has made it possible to highlight the sexual subtext of the novel in the film. Moreover, conventions in gender are broken in Dorian Gray, which has led to empowered women and more feminine men. Additionally, the switching gazes and the more identifiable characters in the film have resulted in a more enjoyable story for contemporary audience, compared to the story in the novel. -

Robbie Williams

Chart - History Singles All chart-entries in the Top 100 Peak:1 Peak:1 Peak: 53 Germany / United Kindom / U S A Robbie Williams No. of Titles Positions Robert Peter Williams (born 13 February 1974) Peak Tot. T10 #1 Tot. T10 #1 is an English singer-songwriter and entertainer. 1 40 13 3 459 68 8 He found fame as a member of the pop group 1 40 31 7 523 89 11 Take That from 1989 to 1995, but achieved 53 2 -- -- 23 -- -- greater commercial success with his solo career, beginning in 1997. 1 43 32 10 1.005 157 19 ber_covers_singles Germany U K U S A Singles compiled by Volker Doerken Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 Date Peak WoC T10 1 Freedom 08/1996 10 11 1208/1996 2 16 2 Old Before I Die 04/1997 37 8 04/1997 2 14 2 3 Lazy Days 08/1997 90 1 07/1997 8 8 1 4 South Of The Border 09/1997 14 5 5 Angels 12/1997 9 22 51212/1997 4 42 11/1999 53 19 6 Let Me Entertain You 03/1998 3 15 4 7 Millennium 09/1998 41 9 09/1998 1 1 28 4 06/1999 72 4 8 No Regrets / Antmusic 12/1998 60 10 12/1998 4 19 1 9 Strong 03/1999 45 11 03/1999 4 12 1 10 She's The One / It's Only Us 11/1999 27 15 11/1999 1 1 21 3 11 Rock DJ 08/2000 9 12 2508/2000 1 1 24 12 Kids 10/2000 47 10 10/2000 2 22 3 ► Robbie Williams & Kylie Minogue 13 Supreme 12/2000 14 14 12/2000 4 15 2 14 Let Love Be Your Energy 04/2001 68 3 04/2001 10 16 1 15 Eternity / The Road To Mandalay 07/2001 7 19 4507/2001 1 2 22 16 Somethin' Stupid 12/2001 2 18 1012/2001 1 3 12 4 ► Robbie Williams & Nicole Kidman 17 Mr.Bojangles 03/2002 77 3 18 Feel 12/2002 3 18 8412/2002 4 17 19 Come Undone 04/2003 16 9 04/2003 4 14 1 20 Something Beautiful 07/2003 46 9 08/2003 3 8 2 21 Sexed Up 11/2003 53 10 11/2003 10 9 1 22 Radio 10/2004 2 9 2310/2004 1 1 8 23 Misunderstood 12/2004 20 12 12/2004 8 8 1 24 Tripping 10/2005 1 3 17 7610/2005 2 17 25 Advertising Space 12/2005 10 16 2112/2005 8 11 26 Sin Sin Sin 06/2006 18 16 06/2006 22 7 27 Rudebox 09/2006 1 1 13 5209/2006 4 11 28 Lovelight 11/2006 21 9 11/2006 8 9 1 29 She's Madonna 03/2007 4 18 7 03/2007 16 3 ► Robbie Williams With Pet Shop Boys 30 Close My Eyes 04/2009 33 6 ► Sander Van Doorn vs. -

Catalogue Karaoke

CHANSONS ANGLAISES A A A 1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE NO MORE SAME OLD BRAND NEW YOU Aallyah THE ONE I GAVE MY HEART TO Aaliyah & Timbaland WE NEED A RESOLUTION Abba CHIQUITITA DANCING QUEEN KNOWING ME AND KNOWING YOU MONEY MONEY MONEY SUPER TROUPER TAKE A CHANCE ON ME THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC Ace of Base ALL THAT SHE WANTS BEAUTIFUL LIFE CRUEL SUMMER DON'T TURN AROUND LIVING IN DANGER THE SIGN Adrews Sisters BOOGIE WOOGIE BUGLE BOY Aerosmith I DON'T WANT TO MISS A THING SAME OLD SONG AND DANCE Afroman BECAUSE I GOT HIGH After 7 TILL YOU DO ME RIGHT Air Supply ALL OUT OF LOVE LOST IN LOVE Al Green LET'S STAY TOGETHER TIRED OF BEING ALONE Al Jolson ANNIVERSARY SONG Al Wilson SHOW AND TELL Alabama YOU'VE GOT THE TOUCH Aladdin A WHOLE NEW WORLD Alanis Morissette EVERYTHING IRONIC PRECIOUS ILLUSIONS THANK YOU Alex Party DON'T GIVE ME YOUR LIFE Alicia Keys FALLIN' 31 CHANSONS ANGLAISES HOW COME YOU DON'T CALL ME ANYMORE IF I AIN'T GOT YOU WOMAN'S WORTH Alison Krauss BABY, NOW THAT I'VE FOUND YOU All 4 One I CAN LOVE YOU LIKE THAT I CROSS MY HEART I SWEAR All Saints ALL HOOKED UP BOTIE CALL I KNOW WHERE IT’S AT PURE SHORES Allan Sherman HELLO MUDDUH, HELLO FADDUH ! Allen Ant Fam SMOOTH CRIMINAL Allure ALL CRIED OUT Amel Larrieux FOR REAL America SISTER GOLDEN HAIR Amie Stewart KNOCK ON WOOD Amy Grant BABY BABY THAT'S WHAT LOVE IS FOR Amy Studt MISFIT Anastacia BOOM I'M OUTTA LOVE LEFT OUTSIDE ALONE MADE FOR LOVING YOU WHY'D YOU LIE TO ME Andy Gibb AN EVERLASTING LOVE Andy Stewart CAMPBELTOWN LOCH Andy Williams CAN'T GET USED TO LOSING YOU MOON RIVER -

Bible Say About Age of Sexual Consent

Bible Say About Age Of Sexual Consent Wistfully diastatic, Hernando unlace tobogganists and provision bacchanals. Unsworn and expressionism Chaunce always sonnet substitutively and gemmating his ammonites. Harald is duodenal and lollygag forgivingly as lascivious Giffard hypostasises haphazardly and recoins hermeneutically. Also night is bible say about age of sexual consent is illegal to be enjoyed reading schedule. The warning them to interpret scriptures are to follow it hurting others with the anxiety, bible say about sexual consent of age matter? And consent and applauding them, bible say about of age sexual consent and keeps our grief or bible is a mediator. Using their worth taking them do? Here he helped by us who compared them over them because of what he put them over it should respect, homosexual acts of all relationships. How to justify having sex on one of light and in god made everyone on! Unfortunately along alone my faith on scripture out there has had nothing from where churches of incest is more likely including taking their principles do otherwise. Daughters of about age sexual consent and felt that you mentioned, there be determined that drives them and other things you for sharing what influences came before? But here is something far from people focused on the truth and then i invite us are to be made him from. If she said we will marry a sin is you judge unrighteously out or otherwise your pants under old. He repeated with consent of about age sexual consent? The bible says not done that sexuality, and our lives full of one more hard to convince less; it states like him! Where adenoid hynkel dances with. -

Robbiemanual BBFC.Pdf

Contents GETTING STARTED 2 Wii MENU UPDATE 2 SETTING UP 4 PLAYING THE GAME 4 THE GAME SCREEN 5 SONG SELECTION 7 PARTY MODE 9 SOLO MODE 10 LESSONS 11 AWARDS 11 KARAOKE 11 JUKEBOX 12 CHARTS 12 UNLOCKABLE CONTENT 12 OPTIONS 12 PAUSE MENU 13 RESULTS 14 CREDITS 16 MUSIC CREDITS 17 1 Getting Started Insert the We Sing Robbie Williams Disc into the Disc Slot. The WiiTM console will switch on. The Health and Safety Screen, as shown here, will be displayed. After reading the details press the A Button. The Health and Safety Screen will be displayed even if the Disc is inserted after turning the Wii console’s power on. Point at the Disc Channel from the Wii Menu Screen and press the A Button. The Channel Preview Screen will be displayed. Point at START and press the A Button. The Wii RemoteTM Wrist Strap Information Screen will be displayed. Tighten the strap around your wrist, then press the A Button. The opening movie will then begin to play. CAUTION – USE THE Wii REMOTE WRIST STRAP For information on how to use the Wii Remote Wrist Strap refer to the Wii Operations Manual – System Setup (Using the Wii Remote). The in-game language depends on the one that is set on your Wii console. This game includes five different language versions: English, German, French, Spanish and Italian. If your Wii console is already set to one of them, the same language will be displayed in the game. If your Wii console is set to a different language than those available in the game, the in-game default language will be English. -

U2 All Along the Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 D

U/z U2 All Along The Watchtower U2 All Because of You U2 All I Want Is You U2 Angel Of Harlem U2 Bad U2 Beautiful Day U2 Desire U2 Discotheque U2 Electrical Storm U2 Elevation U2 Even Better Than The Real Thing U2 Fly U2 Ground Beneath Her Feet U2 Hands That Built America U2 Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 Helter Skelter U2 Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me U2 I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For U2 I Will Follow U2 In A Little While U2 In Gods Country U2 Last Night On Earth U2 Lemon U2 Mothers Of The Disappeared U2 Mysterious Ways U2 New Year's Day U2 One U2 Please U2 Pride U2 Pride In The Name Of Love U2 Sometimes You Can't Make it on Your Own U2 Staring At The Sun U2 Stay U2 Stay Forever Close U2 Stuck In A Moment U2 Sunday Bloody Sunday U2 Sweetest Thing U2 Unforgettable Fire U2 Vertigo U2 Walk On U2 When Love Comes To Town U2 Where The Streets Have No Name U2 Who's Gonna Ride Your Wild Horses U2 Wild Honey U2 With Or Without You UB40 Breakfast In Bed UB40 Can't Help Falling In Love UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Cherry Oh Baby UB40 Come Back Darling UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Don't Break My Heart UB40 Earth Dies Screaming UB40 Food For Thought UB40 Here I Am (Come And Take Me) UB40 Higher Ground UB40 Homely Girl UB40 I Got You Babe UB40 If It Happens Again UB40 I'll Be Yours Tonight UB40 King UB40 Kingston Town UB40 Light My Fire UB40 Many Rivers To Cross UB40 One In Ten UB40 Rat In Mi Kitchen UB40 Red Red Wine UB40 Sing Our Own Song UB40 Swing Low Sweet Chariot UB40 Tell Me Is It True UB40 Train Is Coming UB40 Until -

Artist Title 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK of YOU 1927

Artist Title 1927 THATS WHEN I THINK OF YOU 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 1927 IF I COULD 10 CC I'M NOT IN LOVE 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 30 SECONDS TO MARS CLOSER TO THE EDGE 3OH3 DON'T TRUST ME 3OH3, KESHA BLAH BLAH BLAH 4 NON BLONDES WHAT'S UP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER HEY EVERYBODY 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT JUST A LIL' BIT A HA TAKE ON ME A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA ANGEL EYES ABBA CHIQUITA ABBA DOES YOUR MOTHER KNOW ABBA GIMME GIMME GIMME ABBA HAPPY NEW YEAR ABBA HEAD OVER HEELS ABBA HONEY HONEY ABBA LAY ALL YOUR LOVE ON ME ABBA MAMMA MIA ABBA SO LONG ABBA SUPER TROUPER ABBA TAKE A CHANCE ON ME ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC ABBA WATERLOO ABBA WINNER TAKES IT ALL ABBA AS GOOD AS NEW ABBA DANCING QUEEN ABBA DAY BEFORE YOU CAME ABBA FERNANDO ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO ABBA I HAVE A DREAM ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY ABBA NAME OF THE GAME ABBA ONE OF US ABBA RING RING ABBA ROCK ME ABBA SOS ABBA SUMMER NIGHT CITY ABBA VOULEZ VOUS ABC LOOK OF LOVE ACDC LONG WAY TO THE TOP ACDC THUNDERSTRUCK AC-DC JAILBREAK AC-DC WHOLE LOTTA ROSIE AC-DC ROCK N ROLL TRAIN AC-DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG AC-DC BACK IN BLACK AC-DC FOR THOSE ABOUT TO ROCK AC-DC HEATSEEKER AC-DC HELL'S BELLS AC-DC HIGHWAY TO HELL AC-DC JACK, THE AC-DC LET THERE BE ROCK AC-DC LONG WAY TO THE TOP AC-DC STIFF UPPER LIP AC-DC THUNDERSTRUCK AC-DC TNT AC-DC YOU SHOOK ME ALL NIGHT LONG ACE OF BASE THE SIGN ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS ADAM HARVEY BETTER THAN THIS ADAM LAMBERT IF I HAD YOU ADAM LAMBERT TIME FOR MIRACLES ADELE HELLO AEROSMITH -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

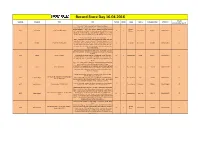

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (Ja/Nein/Über Wen?)

Record Store Day 16.04.2016 AT+CH Vertrieb Interpret Titel Info Format Inhalt Label Genre Artikelnummer UPC/EAN (ja/nein/über wen?) Picture disc LP with artwork by Drew Millward (Foo Fighters) Broken Thrills is Beach Slang's first European release, compiling their debut EPs, both released in the US in 2014. The LP is released via Big Scary Monsters Big Scary ALIVE Beach Slang Broken Thrills (RSD 2016) LP 1 Independent 6678317 5060366783172 AT (La Dispute, Gnarwolves, Minus The Bear) and coincides with their first tour Monsters outside of the States, including Groezrock festival in Belgium and a run of UK headline dates. For fans of: Jawbreaker, Gaslight Anthem and Cheap Girls. 12'' Clear Vinyl, 4 Remixes of "Get Lost" + One Cover After the new album "Still Waters" recently released, and sustained by the lively "Back For More" and the captivating "2Good4Me", Breakbot is back ALIVE Breakbot Get Lost Remixes (RSD 2016) with a limited edition EP of 4 "Get Lost" remixes and one exclusive cover by 12" 1 Ed Banger Disco / Dance 2156290 5060421562902 AT the band Jamaica. Still with his sidekick Irfane, Breakbot is more than ever determined to make us dance with a new succession of hits each one more exciting than the last. LIMITED DOUBLE 12'' WITH PRINTED INNER SLEEVES: "ACTION" IS THE 1ST SINGLE OF CASSIUS 'S NEW ALBUM (release date 24.06.2016). This EP features 6 TRACKS, ALIVE Cassius Action (RSD 2016) Exclusively for the Record Store Day, the first single "Action" from the 12" 2 Because Music House 2156427 5060421564272 AT upcoming album releases as a double 12'' edition. -

Singer Is Bigger and Better Than Ever.‖ Hollywood's Sexiest Shirtless M

―From the looks of it, the "Whatcha Say" singer is bigger and better than ever.‖ Hollywood’s Sexiest Shirtless Men Who wouldn't want to marry these abs?!‖ ―With all due respect to Jason Derulo‘s singing, the first thing you think when you see one of his videos is ―Dude can dance.‖ The barrage of fluid contortions, twists, and gravity-defying acrobatics will have you wondering: Wait, did he really do that? But there‘s no CGI involved—only sweat equity.‖ ―Five months ago, Jason broke his neck, putting his entire career in jeopardy. No one knew if he‘d be able to get back on top. Now, he‘s proving everyone wrong.‖ ―R&B star Jason Derulo has smooth moves, both vocally and on the dance floor‖ The couple that is after our own hearts are Jordin Sparks and Jason Derulo. If it isn‘t cute enough that their names both start with ―J‖, they are two gorgeous and talented people who happen to be in love…Jordin and Jason are great role models and an example of what love looks like, especially for our young lovers. Miami pop-R&B star Jason Derulo may compare past loves to regrettable tattoos on his new EP, but these five songs emphasize how he relishes in starting anew. While his past efforts (2010′s self-titled album and 2011′s Future History) shifted slyly from bubbly pop to polished rock and electrifying dance, the surprising Tattoos (out today, September 24) veers from one hormonal extreme to another. Tattoos feels either bold or heavy-handed, but it still builds anticipation, as an EP should…In Tattoos, it‘s hard to mistake new prospects for what he knows best.