Evaluation of the Biffa Award Programme Final Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shanks Group Plc Annual Report and Accounts 2005

Annual Report and Accounts 2005 Shanks Group plc Shanks Group plc Annual Report and Accounts 2005 company information. CORPORATE HEAD OFFICE REGISTERED OFFICE One of Europe's largest independent waste management companies, Shanks Group plc Shanks Group plc Astor House Shanks House Shanks Group plc has operations in the UK, Belgium and the Netherlands Station Road 211 Blochairn Road and is a leading player in each of these markets. Beyond Europe, Shanks Bourne End Blochairn Buckinghamshire SL8 5YP Glasgow G21 2RL also has activities through its environmental remediation services. Tel: 00 44 (0) 1628 524523 Registered in Scotland No. 77438 The Group provides an extensive range of waste and resource Fax: 00 44 (0) 1628 524114 website: www.shanks.co.uk management solutions and handles a wide variety of wastes, including e-mail: [email protected] domestic refuse, commercial waste, contaminated spoils and hazardous waste. Services offered include collections, domestic and commercial PRINCIPAL OFFICES waste recycling, resource recovery, composting, mechanical biological treatment, thermal treatment, industrial cleaning, special waste treatment UNITED KINGDOM BELGIUM THE NETHERLANDS Shanks Waste Management Shanks Belgium Shanks Nederland and modern disposal. Dunedin House Rue Edouard Belin, 3/1 PO Box 171 Auckland Park BE-1435 3000 AD Rotterdam Further information about the Group and its activities is available on our Mount Farm Mont Saint Guibert The Netherlands Milton Keynes Belgium Tel: 00 31 (0) 10 280 5300 website: www.shanks.co.uk Buckinghamshire MK1 1BU Tel: 00 32 (0) 1023 3660 Fax: 00 31 (0) 10 280 5311 Tel: 00 44 (0) 1908 650650 Fax: 00 32 (0) 1023 3661 Fax: 00 44 (0) 1908 650699 corporate advisers. -

Mechanical Biological Treatment – 15 Years of UK Experience

2017 Briefing Report: Mechanical Biological Treatment – 15 Years of UK Experience September 2017 © Tolvik Consulting Ltd, 2017 2017 Briefing Report: UK MBT Experience Issue Number 1 Date 07.09.17 Author APJ This report has been prepared by Tolvik Consulting Ltd on an independent basis using our knowledge of the current UK waste market and with reference inter alia to various published reports and studies and to our own in-house analysis. This knowledge has been built up over time and in the context of our prior work in the waste industry. This report has been prepared by Tolvik Consulting Ltd with all reasonable skill, care and diligence as applicable. We do not warrant the accuracy of information provided. Whilst we have taken reasonable precautions to check the accuracy of information contained herein, the advice contained within the report is generic and we would strongly recommend that any assumptions be verified on a project specific basis. Tolvik Consulting Ltd shall not be responsible for the consequences (whether direct or indirect) of any such decisions. Copyright in this document is reserved to ourselves. The report is personal to the Licensee and may not be reproduced by a Licensee without prior authority by ourselves and due acknowledgement of source. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................ 2 1. INTRODUCTION AND CONTEXT ................................................................................................. -

FTSE Russell Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 19 August 2021 FTSE 250 Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 June 2021 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) 3i Infrastructure 0.43 UNITED Bytes Technology Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Investment Trust 0.25 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 4imprint Group 0.18 UNITED C&C Group 0.23 UNITED Edinburgh Worldwide Inv Tst 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM 888 Holdings 0.25 UNITED Cairn Energy 0.17 UNITED Electrocomponents 1.18 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aberforth Smaller Companies Tst 0.33 UNITED Caledonia Investments 0.25 UNITED Elementis 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Aggreko 0.51 UNITED Capita 0.15 UNITED Energean 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Airtel Africa 0.19 UNITED Capital & Counties Properties 0.29 UNITED Essentra 0.23 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AJ Bell 0.31 UNITED Carnival 0.54 UNITED Euromoney Institutional Investor 0.26 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Alliance Trust 0.77 UNITED Centamin 0.27 UNITED European Opportunities Trust 0.19 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Allianz Technology Trust 0.31 UNITED Centrica 0.74 UNITED F&C Investment Trust 1.1 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM AO World 0.18 UNITED Chemring Group 0.2 UNITED FDM Group Holdings 0.21 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Apax Global Alpha 0.17 UNITED Chrysalis Investments 0.33 UNITED Ferrexpo 0.3 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ascential 0.4 UNITED Cineworld Group 0.19 UNITED Fidelity China Special Situations 0.35 UNITED KINGDOM KINGDOM KINGDOM Ashmore -

Download Report

Business Superbrands 2015 Top 20 Business Superbrands BRAND CATEGORY British Airways 1 Travel - Airlines Apple 2 Technology - Hardware & Equipment Virgin Atlantic 3 Travel - Airlines Microsoft 4 Information Technology - General Visa 5 Financial - Credit Cards & Payment Solutions MasterCard 6 Financial - Credit Cards & Payment Solutions Google 7 Advertising Solutions FedEx 8 Courier, Delivery & Postal Services IBM 9 Information Technology - General Samsung 10 Technology - Hardware & Equipment Johnson & Johnson 11 Pharmaceuticals & Medical Equipment BT 12 Telecommunications - General Rolls-Royce Group 13 Aerospace & Defence American Express 14 Financial - Credit Cards & Payment Solutions Royal Mail 15 Courier, Delivery & Postal Services PayPal 16 Financial - Credit Cards & Payment Solutions BP 17 Oil & Gas - General Shell 18 Oil & Gas - General Bosch 19 Construction - Tools & Equipment Manufacturers Boeing 20 Aerospace & Defence Category Winners BRAND CATEGORY Deloitte Accountancy & Business Services Google Advertising Solutions Rolls-Royce Group Aerospace & Defence Tate & Lyle Agribusiness BMA (British Medical Association) Associations & Accreditations BASF Chemicals Haymarket Conferences & Events - Owners & Organisers NEC Conferences & Events - Venues Wickes Construction - Builders Merchants & Distributors Balfour Beatty Construction - Consultancy, Design, Build & Management Pilkington Construction - Materials HSS Hire Construction - Plant & Tool Hire Bosch Construction - Tools & Equipment Manufacturers FedEx Courier, Delivery & Postal -

The UK Private Equity IPO Report

THE UK PRIVATE EQUITY IPO REPORT Private equity-backed IPOs: 1 January 2009 – 31 December 2017 IN ASSOCIATION WITH 2 | THE UK PRIVATE EQUITY IPO REPORT CONTENTS FOREWORD 03 HISTORIC ANALYSIS OF PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED IPOS IN THE UK 04 BETWEEN 1 JANUARY 2009 AND 31 DECEMBER 2017 VOLUME AND VALUE OF PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED IPOS LISTING IN THE UK 05 TOP 10 PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED IPOS 06 INDUSTRIES 07 FREE FLOAT 12 USE OF PROCEEDS 13 PRICING 14 PERFORMANCE 15 ANALYSIS OF ACTIVE PRIVATE EQUITY HOUSES BY SIZE 17 LOCK-UP PERIODS 18 HOLDING PERIODS 20 PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED IPO ACTIVITY IN 2017 21 APPENDIX 23 PRIVATE EQUITY-BACKED IPOS 1 JANUARY 2009 - 31 DECEMBER 2017 23 METHODOLOGY 31 CONTACTS 32 3 | THE UK PRIVATE EQUITY IPO REPORT FOREWORD Public markets have long been an important exit route for private equity houses selling their stakes into the companies they have backed, yet little research has been conducted into how these businesses perform after they have floated. This report, published by the BVCA and PwC, provides an historic analysis of private equity-backed IPOs in the UK between 1 January 2009 and 31 December 2017. It looks at a number of metrics including the use of proceeds, pricing and performance to build a picture of the IPO market and the key trends with the market. The performance numbers are particularly revealing as they show that private equity-backed IPOs are trading on average 43.9% higher than their offer price for the period from IPO to 31 December 2017 compared to the non-private equity-backed IPOs of the same period which are trading at an average of 26.6% higher. -

State Street AUT UK Screened (Ex Controversies and CW) Index

Report and Financial Statements For the year ended 31st December 2020 State Street AUT UK Screened (ex Controversies and CW) Index Equity Fund (formerly State Street UK Equity Tracker Fund) State Street AUT UK Screened (ex Controversies and CW) Index Equity Fund Contents Page Manager's Report* 1 Portfolio Statement* 9 Director's Report to Unitholders* 27 Manager's Statement of Responsibilities 28 Statement of the Depositary’s Responsibilities 29 Report of the Depositary to the Unitholders 29 Independent Auditors’ Report 30 Comparative Table* 33 Financial statements: 34 Statement of Total Return 34 Statement of Change in Net Assets Attributable to Unitholders 34 Balance Sheet 35 Notes to the Financial Statements 36 Distribution Tables 48 Directory* 49 Appendix I – Remuneration Policy (Unaudited) 50 Appendix II – Assessment of Value (Unaudited) 52 * These collectively comprise the Manager’s Report. State Street AUT UK Screened (ex Controversies and CW) Index Equity Fund Manager’s Report For the year ended 31st December 2020 Authorised Status The State Street AUT UK Screened (ex Controversies and CW) Index Equity Fund (the “Fund”) is an Authorised Unit Trust Scheme as defined in section 243 of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 and it is a UCITS Retail Scheme within the meaning of the FCA Collective Investment Schemes sourcebook. The unitholders are not liable for the debts of the Fund. The Fund's name was changed to State Street AUT UK Screened (ex Controversies and CW) Index Equity Fund on 18th December 2020 (formerly State Street UK Equity Tracker Fund). Investment Objective and Policy The objective of the Fund is to replicate, as closely as possible and on a “gross of fees” basis, the return of the United Kingdom equity market as represented by the FTSE All-Share ex Controversies ex CW Index (the “Index”), net of withholding taxes. -

Excavated Material and Waste Management Strategy Overview Of

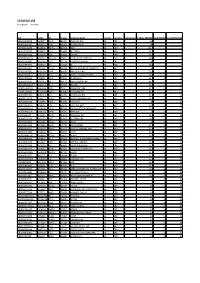

Excavated Material and Waste Management Strategy Overview of Strategy Volume 1 of 3 February 2005 This document has been prepared for the titled project or named part thereof and shouldnot be relied upon or used for any other project without an independent check being carried out as to its suitability and prior written authority of Mott MacDonald being obtained. Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for the consequences of this document being used for a purpose other than the purposes for which it was commissioned. Any person using or relying on the document for such other purpose agrees, and will by such use or reliance be taken to confirm his agreement to indemnify Mott MacDonald for all loss or damage resulting thereof. Mott MacDonald accepts no responsibility or liability for this document to any party other than the person by whom it was commissioned. Excavated Material and Waste Management Strategy Mott MacDonald Overview of Strategy 18 February 2005 List of Contents Page Sections and Appendices 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Summary Scheme Description 1 1.3 Route Definitions 1 1.4 Technical Report Format 2 1.5 Excavated Materials and Waste Management Strategy 3 2 CATEGORIES OF SURPLUS MATERIAL 4 2.1 Material Types 4 2.2 Demolition Material (estimated volume 0.3 million m3) 4 2.3 Excavated Material (estimated volume 6.0 million m3) 4 2.3.1 Clean Excavated Material 4 (i) Subsurface works: 5 (ii) Surface works: 5 2.3.2 Contaminated excavated material (estimated volume 0.5 million m3) 5 2.4 Construction Material -

M Funds Quarterly Holdings 3.31.2020*

M International Equity Fund 31-Mar-20 CUSIP SECURITY NAME SHARES MARKET VALUE % OF TOTAL ASSETS 233203421 DFA Emerging Markets Core Equity P 2,263,150 35,237,238.84 24.59% 712387901 Nestle SA, Registered 22,264 2,294,710.93 1.60% 711038901 Roche Holding AG 4,932 1,603,462.36 1.12% 690064001 Toyota Motor Corp. 22,300 1,342,499.45 0.94% 710306903 Novartis AG, Registered 13,215 1,092,154.20 0.76% 079805909 BP Plc 202,870 863,043.67 0.60% 780087953 Royal Bank of Canada 12,100 749,489.80 0.52% ACI07GG13 Novo Nordisk A/S, Class B 12,082 728,803.67 0.51% B15C55900 Total SA 18,666 723,857.50 0.51% 098952906 AstraZeneca Plc 7,627 681,305.26 0.48% 406141903 LVMH Moet Hennessy Louis Vuitton S 1,684 625,092.87 0.44% 682150008 Sony Corp. 10,500 624,153.63 0.44% B03MLX903 Royal Dutch Shell Plc, Class A 35,072 613,753.12 0.43% 618549901 CSL, Ltd. 3,152 571,782.15 0.40% ACI02GTQ9 ASML Holding NV 2,066 549,061.02 0.38% B4TX8S909 AIA Group, Ltd. 60,200 541,577.35 0.38% 677062903 SoftBank Group Corp. 15,400 539,261.93 0.38% 621503002 Commonwealth Bank of Australia 13,861 523,563.51 0.37% 092528900 GlaxoSmithKline Plc 26,092 489,416.83 0.34% 891160954 Toronto-Dominion Bank (The) 11,126 473,011.14 0.33% B1527V903 Unilever NV 9,584 472,203.46 0.33% 624899902 KDDI Corp. -

Nomura-Greentech-Oct

Sustainable Technology and Infrastructure Monthly Market Update // October 2020 Performance of Key Market Indices1 140.0% 120.0% 100.0% 109.1% 80.0% 60.0% 40.0% 28.6% 20.0% 0.0% 5.8% (20.0%) 1.0% (40.0%) Oct-19 Dec-19 Feb-20 Apr-20 Jun-20 Aug-20 Oct-20 NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy MSCI World Index NASDAQ Composite S&P 500 Index Performance1 October Ending Versus First Day of the October YTD CY 2019 52 Wk High 52 Wk Low MSCI World Index (3.1%) (2.8%) 25.2% (8.1%) 43.1% NASDAQ Composite (2.3%) 21.6% 35.2% (9.5%) 59.0% S&P 500 (2.8%) 1.2% 28.9% (8.7%) 46.1% NASDAQ Clean Edge Green Energy 6.9% 90.2% 40.7% (6.8%) 179.6% Denotes Nomura Notable Recent Transactions & Capital Raises Greentech Transaction Date Target Acquiror Transaction Description Veolia, a French water and energy utility, acquired a 30% stake in Suez, a French water Oct. 5 Suez Veolia and wastewater utility, from Engie for $13.2bn Corporate M&A Generac Power Systems, a U.S. manufacturer of power generation products, Transactions Oct. 6 Enbala Generac announced the signing of an agreement to acquire Enbala Power Networks, a virtual power plant and distributed energy resource management platform Fluence, a Siemens and AES joint venture for energy storage, acquired Advanced Advanced Microgrid Oct. 15 Fluence Microgrid Solutions (AMS), a San Francisco-based developer of software for clean Solutions energy asset optimization Date Company Transaction Description Capital Raises Array Technologies, an Oaktree-backed U.S. -

Company Company Contribution Details 3I Matched 3I Deutschland

Company Company Contribution Details Column1 Check 3i Matched 3i Deutschland GmbH Matched 3M Matched A.F. Blakemore & Sons Ltd A.T. Kearney Matched Abbey National plc Matched £700 per year Aberdeen Asset Management Matched ABN Amro Bank Matched Accenture Matched Adnams AES Corporation & Kilroot Power LTD Aim Morrison supermarkets Aimia Air products ltd Matched Alfred Dunhill Ltd Matched Allen & Overy Alliance & Leicester plc Matched 250 per employee, 2 x year, max £1 000, match childrens 0f £25 2 x per year Alliance Capital Ltd Matched Amec PLC Matched American Express Matched Amlin Insurance Matched Amoco Foundation Matched Amoco Foundation Inc Matched AMP Andersen Matched Anglian Water Matched Anglo American Aon Apple EMEA Arcadia Group Argo Wiggins Matched Argos Matched Arla Foods Matched ARM Holdings Matched Arriva London Matched ASDA Matched ASOS.com Matched Aspect capital ASSEAL AstraZeneca Matched AT Kearney Matched Atari UK Aurum Aviva Avon Cosmetics Ltd Matched AXA PPT B&Q Matched BAA PLC Ltd Matched Bain & Company Matched Bank of America Matched Up to £600 per year Bank of England Matched Bank of Scotland Matched Matched to £500 Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi Matched Bankers Trust Matched Barclays Bank Matched £750 per employee 3 x year Barclays Capital Matched £750 per employee 3 x year Barclays Group Matched £750 per employee 3 x year Bayer Plc Matched BBC Beaverbrooks Jewellers Matched Bell Atlantic Network Services Matched BG Group Matched Bibby Line Group Biffa Blackbaud Europe Ltd BOC Group Matched Boeing Commercial Airplanes -

Equiniti Group Plc (The “Company”) Prepared in Accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority (The “FCA”)

THIS DOCUMENT AND THE ACCOMPANYING DOCUMENTS ARE IMPORTANT AND REQUIRE YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION. If you are in any doubt as to what action you should take, you are recommended to seek your own personal financial advice immediately from your stockbroker, bank, solicitor, accountant, fund manager or other appropriate independent financial adviser, who is authorised under the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (the “FSMA”) if you are resident in the United Kingdom or, if not, from another appropriately authorised independent financial adviser. This document is a prospectus (the "Prospectus") relating to Equiniti Group plc (the “Company”) prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority (the “FCA”). This Prospectus has been approved by the FCA in accordance with section 85 of FSMA, will be made available to the public and has been filed with the FCA in accordance with the Prospectus Rules. This Prospectus together with the documents incorporated into it by reference (as set out in Part XIX (Information Incorporated by Reference) of this Prospectus) will be made available to the public in accordance with Prospectus Rule 3.2.1 by the same being made available, free of charge, at www.equiniti.com and at the Company’s registered office at Sutherland House, Russell Way, Crawley, West Sussex, RH10 1UH. If you sell or have sold or have otherwise transferred all of your Shares (other than ex rights) held in certificated form before 8.00 am (London time) on 29 September 2017 (the “Ex Rights Date”), please send this Prospectus, together with any Provisional Allotment Letter duly renounced, if and when received, at once to the purchaser or transferee or to the bank, stockbroker or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for delivery to the purchaser or transferee except that such documents should not be sent to any jurisdiction where to do so might constitute a violation of local securities laws or regulations, including but not limited to the United States or any of the Excluded Territories. -

STOXX UK 180 Selection List

STOXX UK 180 Last Updated: 20210301 ISIN Sedol RIC Int.Key Company Name Country Currency Component FF Mcap (BEUR) Rank (FINAL)Rank (PREVIOUS) GB00B10RZP78 B10RZP7 ULVR.L 091321 UNILEVER PLC GB GBP Y 113 1 1 GB0009895292 0989529 AZN.L 098952 ASTRAZENECA GB GBP Y 105 2 2 GB0005405286 0540528 HSBA.L 040054 HSBC GB GBP Y 101.6 3 3 GB0007188757 0718875 RIO.L 071887 RIO TINTO GB GBP Y 76.5 4 7 GB0002374006 0237400 DGE.L 039600 DIAGEO GB GBP Y 75.8 5 4 GB00B03MLX29 B09CBL4 RDSa.AS B09CBL ROYAL DUTCH SHELL A GB EUR Y 69.3 6 8 GB0009252882 0925288 GSK.L 037178 GLAXOSMITHKLINE GB GBP Y 69 7 5 GB0007980591 0798059 BP.L 013849 BP GB GBP Y 68.3 8 9 GB0002875804 0287580 BATS.L 028758 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO GB GBP Y 62 9 6 GB00BH0P3Z91 BH0P3Z9 BHPB.L 005666 BHP GROUP PLC. GB GBP Y 55.2 10 11 GB00B24CGK77 B24CGK7 RB.L 072769 RECKITT BENCKISER GRP GB GBP Y 50.9 11 10 GB0007099541 0709954 PRU.L 070995 PRUDENTIAL GB GBP Y 42.3 12 14 GB00B1XZS820 B1XZS82 AAL.L 490151 ANGLO AMERICAN GB GBP Y 40.5 13 15 GB00B2B0DG97 B2B0DG9 REL.L 073087 RELX PLC GB GBP Y 38.6 14 12 GB00BH4HKS39 BH4HKS3 VOD.L 071921 VODAFONE GRP GB GBP Y 37.7 15 13 JE00B4T3BW64 B4T3BW6 GLEN.L GB10B3 GLENCORE PLC GB GBP Y 36.5 16 18 GB00BDR05C01 BDR05C0 NG.L 024282 NATIONAL GRID GB GBP Y 32.7 17 16 GB0008706128 0870612 LLOY.L 087061 LLOYDS BANKING GRP GB GBP Y 31.8 18 22 GB0031348658 3134865 BARC.L 007820 BARCLAYS GB GBP Y 30 19 23 GB00BD6K4575 BD6K457 CPG.L 053315 COMPASS GRP GB GBP Y 29.9 20 21 GB00B0SWJX34 B0SWJX3 LSEG.L 095298 LONDON STOCK EXCHANGE GB GBP Y 25.2 21 17 GB00B19NLV48 B19NLV4