RCED-84-9 Increasing HUD Effectiveness Through Improved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

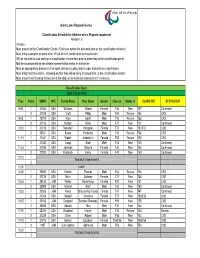

PI Classification Schedule GLRG.Xlsx

Great Lakes Regional Games Classification Schedule for Athletes with a Physical Impairment Version 1.6 Athletes - Must present to the Classification Centre 15 minutes before the allocated time on the classification schedule. Must bring a passport or some other official form of identification to classification. Will be required to read and sign a classification release form prior to presenting to the classification panel. May be accompanied by one athlete representative and/or an interpreter. Must be appropriately dressed in their sport clothes including shorts under tracksuits and sport shoes. Must bring their track chairs, strapping etc that they will be using in competition, to the classification session. Must ensure their throwing frames are at the stadium for technical assessments if necessary. Classification Day 1 Date: 9 June 2016 Time Panel SDMS NPC Family Name First Name Gender Class In Status In CLASS OUT STATUS OUT 9:00 1 31066 USA Williams Taleah Female T46 New T47 Confirmed 2 31008 USA Croft Philip Male T54 Review T54 CRS 9:45 1 15912 USA Rigo Isaiah Male T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31016 USA Nelson Brian Male F37 New F37 Confirmed 10:30 1 31218 USA Beaudoin Margaret Female T37 New T37/F37 CNS 2 30821 USA Evans Frederick Male T34 Review F34 CRS 11:15 1 11241 USA Weber Amberlynn Female T53 Review T53 CRS 2 31330 USA Langi Siale Male F43 New F43 Confirmed 11:45 1 31098 USA Johnson Shayna Female T44 New T44 Confirmed 2 27200 USA Frederick Emily Female F40 New F40 Confirmed 12:15 1 Technical Assessments 2 13:00 Lunch 14:00 1 20880 USA -

Athletics Classification Rules and Regulations 2

IPC ATHLETICS International Paralympic Committee Athletics Classifi cation Rules and Regulations January 2016 O cial IPC Athletics Partner www.paralympic.org/athleticswww.ipc-athletics.org @IPCAthletics ParalympicSport.TV /IPCAthletics Recognition Page IPC Athletics.indd 1 11/12/2013 10:12:43 Purpose and Organisation of these Rules ................................................................................. 4 Purpose ............................................................................................................................... 4 Organisation ........................................................................................................................ 4 1 Article One - Scope and Application .................................................................................. 6 International Classification ................................................................................................... 6 Interpretation, Commencement and Amendment ................................................................. 6 2 Article Two – Classification Personnel .............................................................................. 8 Classification Personnel ....................................................................................................... 8 Classifier Competencies, Qualifications and Responsibilities ................................................ 9 3 Article Three - Classification Panels ................................................................................ 11 4 Article Four -

12/4/2013 Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Category Codes

12/4/2013 Lawful Permanent Resident (LPR) Category Codes Description Initial INS Class of INS Status Sponsored Status Section of Law Code Y/N* Admission Code A11 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A12 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A16 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A17 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A31 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A32 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A33 LA AM N Amerasians and family members from Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, or Vietnam A36 LA AM N Married Amerasian son or daughter of a U.S. Sec. 203(a)(3) of the I&N Act and citizen born in Cambodia, Korea, Laos, Thailand, 204(g) as added by PL 97-359 (Oct. or Vietnam. 22, 1982) A37 LA AM N Spouse of an alien classified as A31 or A36. Sec. 203(d) of the I&N Act and 204(g) as added by PL 97-359 (Oct. 22, 1982) A38 LA AM N Child of an alien classified as A31 or A36. Sec. 203(d) of the I&N Act and 204(g) as added by PL 97-359 (Oct. 22, 1982) AA1 LA NR N Diversity visa lottery winners and dependents, 1991-1994 AA2 LA NR N Diversity visa lottery winners and dependents, 1991-1995 AA3 LA NR N Diversity visa lottery winners and dependents, 1991-1996 AA6 LA NR N Diversity visa lottery winners and dependents, 1991-1997 AA7 LA NR N Diversity visa lottery winners and dependents, 1991-1998 AA8 LA NR N Diversity visa lottery winners and dependents, 1991-1999 AM1 LA AM N Amerasian born in Vietnam after Jan. -

Classification Report

World Para Athletics Classification Master List Summer Season 2017 Classification Report created by IPC Sport Data Management System Sport: Athletics | Season: Summer Season 2017 | Region: Oceania Region | NPC: Australia | Found Athletes: 114 Australia SDMS ID Family Name Given Name Gender Birth T Status F Status P Status Reason MASH 14982 Anderson Rae W 1997 T37 R F37 R-2024 10627 Arkley Natheniel M 1994 T54 C 33205 Ault-Connell Eliza W 1981 T54 C 1756 Ballard Angela W 1982 T53 C 26871 Barty Chris M 1988 T35 R F34 R MRR 1778 Beattie Carlee W 1982 T47 C F46 C 26763 Bertalli James M 1998 T37 R F37 R 17624 Blake Torita W 1995 T38 R-2022 32691 Bounty Daniel M 2001 T38 R-2022 13801 Burrows Thomas M 1990 T20 [TaR] R 29097 Byrt Eliesha W 1988 T20 [TaR] C 32689 Carr Blake M 1994 T20 [HozJ] C F20 N 10538 Carter Samuel M 1991 T54 C 1882 Cartwright Kelly W 1989 T63 C F63 C 29947 Charlton Julie W 1999 T54 C F57 C 1899 Chatman Aaron M 1987 T47 C 29944 Christiansen Mitchell M 1997 T37 R-2025 26224 Cleaver Erin W 2000 T38 R-2022 19971 Clifford Jaryd M 1999 T12 R-2023 F12 R-2023 29945 Colley Tamsin W 2002 T36 R-2023 F36 R-2020 1941 Colman Richard M 1984 T53 C 26990 Coop Brianna W 1998 T35 R-2022 19721 Copas Stacey W 1978 T51 R F52 C 32680 Crees Dayna W 2002 F34 R-2022 29973 Crombie Cameron M 1986 F38 R-2022 19964 Cronje Jessica W 1998 T37 R F37 R IPC Sport Data Management System Page 1 of 4 6 October 2021 at 07:08:42 CEST World Para Athletics Classification Master List Summer Season 2017 19546 Davidson Brayden M 1997 T36 R-2022 1978 Dawes Christie W -

(VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans

Revised May 23, 2019 U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Monthly Assistance Allowance for Disabled Veterans Training in Paralympic and Olympic Sports Program (VMAA) In partnership with the United States Olympic Committee and other Olympic and Paralympic entities within the United States, VA supports eligible service and non-service-connected military Veterans in their efforts to represent the USA at the Paralympic Games, Olympic Games and other international sport competitions. The VA Office of National Veterans Sports Programs & Special Events provides a monthly assistance allowance for disabled Veterans training in Paralympic sports, as well as certain disabled Veterans selected for or competing with the national Olympic Team, as authorized by 38 U.S.C. 322(d) and Section 703 of the Veterans’ Benefits Improvement Act of 2008. Through the program, VA will pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with either a service-connected or non-service-connected disability if the Veteran meets the minimum military standards or higher (i.e. Emerging Athlete or National Team) in his or her respective Paralympic sport at a recognized competition. In addition to making the VMAA standard, an athlete must also be nationally or internationally classified by his or her respective Paralympic sport federation as eligible for Paralympic competition. VA will also pay a monthly allowance to a Veteran with a service-connected disability rated 30 percent or greater by VA who is selected for a national Olympic Team for any month in which the Veteran is competing in any event sanctioned by the National Governing Bodies of the Olympic Sport in the United State, in accordance with P.L. -

020587 2 55 Lm)Ex 0F Sitrets Alld SIINDIR0 Draffi{GS INDEX of SHEETS

OAI€ orrE OIIE OAIE SrttE FEAO M SEI IOTA Evrsto Fllfo itus[0 Flra0 E STCEIS 6 ARl(. J6 r(L 0205E7 1 55 COUNTY OESH COUNIY ARKANSAS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION LINCOLN J ABTES CREEK STR- & APPRS. (S' CONSTRUCTION PLANS FOR STATE HIGHWAY @ D z of ABTES CREEK STR. & APPRS" (S) @ ot o I o DREW COUNTY N L ROUTE I38 SECTION 5 w i I z ___I_ PROJECT l @ o o 0205E7 LOCAT I ON T JoB { Locey o !JE FED AID PROJ NHPP_OC2?(31 ) ARK. HWY. DIST. NO. 2 ASHLEY NOT TO SCALE VICINITY MAP DESIGN TRAFFIC DATA R5W DESIGN YEAR- -----2O3A R4W 2OI8 ADT 800 t' ADT OOO 6 t' 2038 I, BRIDGE DATA 2038 DHV I to STA. 2r7+96.50 DIRECT I ONAL DI STRIBUT I ON- - -O. 60 o BRIDGE N0.07426 T 170'-0" coNTrNuous couPostTE INTEGRAL TRUCKS_ _______42 W-BEAM UN|T (40',-45',-,15',-40',r lt DESIGN SPEED 55 MPH 30,-0" CLEAR ROADIIAY I7I'-0" BRIDGE LENGTH I sTA. 219+67.50 S T N il S STA. 21 1 * 50. OO J LOG MILE I5.8I STA. 229* 50. OO END JOB O2O5A7 !l APPROVED ao T 6|o (\ (\t t2 T o S fl, t2 R5W R4W S oz q GROSS LENGTH OF PROJECT r800.00 FEET OR 0.34I MILES DEPUTY DIRECTOR BEGINNING OF PROJECT MID POINT OF PROJECT END OF PROJECT " ROADWAY r629.00 @ NET " 0.309 AND CHIEF ENGINEER (! " BRIDGES 17t.00 o LATITUDE = N 33'44'04- LATTTUDE = N 33'41'12" LATITUoE = N 33'44'19" NET " 0.032 N NET " " PROJECT r800.00 0.341 o LONGITUDE = lY 9l'35'15" LONGITUOE = u 9l'33'40" LONGITUDE = lI 9l'31'33" e. -

A Study of Two Populations of Merluccius Bilinearis (Mitchill)

,'j, "" :1 • UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ~ 2 DATE. 7110/ , i • ~-- .~ ~~~"'~...c.-- , , ~ • ~ November 20, 1958 John P. Wise " Robert L. Edward.$., Ms., ''Population estimates of whiting (Merluccius bi1inearis) ,I stocks by the Delury regression technique," by D. Oberacker 'j Please review and cowJllent. Robert L. Edwards Enclosure + Office Memorandum · UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT ';, II TO J.A. Posgay DATE: June ~9 .. 1958 ! FROM J.P. Hise SUBJECT: Oberacker's ms. on estimation of Hhiting populations. ~-Jith regard to the inquiry in the TIeTIO of Cl:rde to the boas, dated June 16, I have examined the thesis. and do not think that the material and conclusions are sufficiently Bound to merit publication. Some of the reasons are these: 1. The author admits t;1at he ca.nnct est:;"mate the strength OI' t.~e offshore population, and his estimate of the strength of the inshore population is roughly plus or minus fifty percent. 2. He discusses "catchable population" but does not define it. Nocrhere is the point brought out that a gooe'. part of the population is partially catchable, 8..Lid partially only-, because of net se16ctiv-ity. 3. In converting pounds of fish to nw':1bers he uses samples IJhich amOlli'1t L'1 total to about seven hundred ~ fish, or, assu.cdng half a pound per fish, to about three hundred and fifty pounds. This is less than one-thousandth of L ~ percent of his estil-nate of the population."Tt'"""CiOe"s'Ii'Ot Seem to me thatvalid conclusions are likely to be clra;mfrom so small a sample. 4. -

English Federation of Disability Sport National Junior Athletics Information and Standards

English Federation of Disability Sport National Junior Athletics Information and standards 1 Contents Introduction 3 EFDS track groupings 4 EFDS field groupings 5 Events available 6 National field weights 8 National standards track 11 National standard field 13 2 Introduction This booklet has been produced with the intention of enabling athletes, coaches, teachers and parents to compare EFDS Profiles and Athletics Groupings with IPC Athletics Classes, the enclosed information is a guide for EFDS Events and IS NOT AN IPC CLASSIFICATION. You can find out further information on classification using the following links: www.englandathletics.org/disability-athletics/eligibility-and-classification UK Classification will allow athletes to: - Enter Parallel Success events across UK - Register times on the UK Rankings (www.thepowerof10.info) - Be eligible for Sainsbury’s School Games selection - Receive monthly Paralympic newsletter from British Athletics For athletes interested in joining an athletics club and seeking a UK Classification please contact. - Shelley Holroyd (England North & East) [email protected] - Job King (England Midlands & South) [email protected] Or complete the following online form. www.englandathletics.org/parallelsuccess The document contains information regarding the events available to athletes, the specific weights for throwing implements relevant to the EFDS Field and Age Groups as well as the qualifying standards for the National Junior Athletics Championships. Our aim is to provide as much information and support as possible so that athletes, regardless of their ability can continue to participate within the sport of athletics. We are committed to delivering multi- disability events that cater for both the needs of the disability community and the relevant NGB pathway for talented athletes. -

The Paralympic Athlete Dedicated to the Memory of Trevor Williams Who Inspired the Editors in 1997 to Write This Book

This page intentionally left blank Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science The Paralympic Athlete Dedicated to the memory of Trevor Williams who inspired the editors in 1997 to write this book. Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science The Paralympic Athlete AN IOC MEDICAL COMMISSION PUBLICATION EDITED BY Yves C. Vanlandewijck PhD, PT Full professor at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Faculty of Kinesiology and Rehabilitation Sciences Department of Rehabilitation Sciences Leuven, Belgium Walter R. Thompson PhD Regents Professor Kinesiology and Health (College of Education) Nutrition (College of Health and Human Sciences) Georgia State University Atlanta, GA USA This edition fi rst published 2011 © 2011 International Olympic Committee Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial offi ces: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

Bonn, 6 February 2018 Para Athletics Tokyo 2020 Medal Event

NPCs Widely and Regularly Practicing Para Athletics Via Email Bonn, 6 February 2018 Para Athletics Tokyo 2020 Medal Event Programme Dear President/Secretary General, World Para Athletics would like to inform you that on the weekend on 27-28 January 2018 the IPC Governing Board confirmed the sport programme for the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games with the overall sport programme of the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games featuring 22 sports. We would now like to provide you with some additional background information on the World Para Athletics medal event programme and the final programme itself. In February 2016, World Para Athletics submitted their event programme request to the International Paralympic Committee (IPC). This request was based on the principles set out in developing the Rio medal event programme and included a requested number of slots and athlete allocation. Following numerous levels of further consultation with NPCs, inputs from Sport Technical Committee and management team, World Para Athletics presented a final draft programme to NPCs during Sport Forums in Frankfurt Germany February 2017 for feedback. Following this exercise, the final programme was concluded taking into account of the classification updates introduced in November 2017. We believe the event programme submitted to the IPC will allow NPCs to continue on the athlete development and performance programme that have been in place prior to Rio Paralympic Games while addressing the need for increased participation opportunities for females and safeguarding event viability and strengthening depth of competition field. The final medal event programme for Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games approved by the IPC Governing Board features 168 medal events (93 male, 64 female and 1 mixed) with an athlete quota allocation of 1100 (630 male and 470 female). -

EXCUSED: Michael Detorakis 1

FAIRLAWN CITY COTJNCIL COMMITTEE OF'THE WHOLE DATE: 05/1312019 TIME: 6:00 PM NAME OF COMMITTEE: COMMITTEE OF THE WHOI,F, CALLED TO ORDER AT: 6:01 PM BY: Russell Shamsky COMI\,IITTEE MEMBERS: Kathleen Baum. Philip Brillhart. Maria Williams. Barbara Potts. and Todd Stock OTHERS: Mayor Roth. Bryan Nace. Emie Staten. Bill Arnold" Chief Duman. Lt. Wisner- [.t- Adams- Chief Caotain Brant- Jacob Kaufman EXCUSED: Michael Detorakis 1. Call to Order 2. Legislation in Committees: COMMITTEE OF THE WHOLE: Ordinance 2019-026 Offered by Mayor Roth AN ORDINANCE AUTHORIZING AND DIRECTING THE APPROPRIATION OF CERTAIN INTERESTS IN REAL PROPERTY REFERRED TO AS PARCEL OOI-WD & WDV NECESSARY FOR THE CLEVELAND-MASSILLON ROAD WIDENING PROJECT AND APPROPRIATING FI]NDS FOR THE PURPOSE THEREOF (Expires 08104/19) (1't Reading 05/06119) Discussion: Mr. Nace commented on situations where acouisitions are not reached and narties need to move to trail for a FINANCE COMMITTEE: Ordinance 2019-023 Offered by Mayor Roth AN ORDINANCE AUTHORIZING VARIOUS APPROPzuATIONS (Expires 08/04/19) (l't Reading 0s/06/19) I)iscussion: Mr. Kaufman commented on adjustments that are needed for 2019 budget. Exhibit forthcomins. PLAIINING COMMITTEE: Ordinance 2019-021 Offered by Mayor Roth AN ORDINANCE AMENDING AND/OR SUPPLEMENTING CFIAPTER IO24 *EXCAVATIONS" OF TITLE TWO "STREET AND SIDEWALK AREAS", PART TEN "STREETS, UTILITIES, AND PUBLIC SERVICES CODE'' OF THE CODIFIED ORDINANCES OF THE CITY OF FAIRLAWN (Expires 07/l4l19) (1't Reading 04/15/19) (2nd Reading 05/06119) Discussion: Code changes needed related to contractors operating in the Citv and not responding to issues annronriatelv or ti 05/13/19 Page I of2 Notes 3. -

Live Scoring for Tournament Golf Skyhawk Invitational Player

3/14/2017 Player Leaderboard Live Scoring for Tournament Golf Skyhawk Invitational 174.223.3.150 Leaderboards: Old Individual | Old Team | New Individual | New Team | New Team with Players Player Leader Board * player is participating as an individual rather than as a team member. Course:Callaway Gardens Lake View: Lake View NAIA Par 72 5804 yards position scoring all rnds total player team current start to par thru today 1 2 score 1 1 Courtney Lowery Point University +1 F +3 70 75 145 2 T3 Sam Burrus Lee University +2 F 2 76 70 146 3 2 Anne Hedegaard Lee University +5 F +2 75 74 149 T4 T14 Tara Rodenhurst Lindsey Wilson Coll. +8 F 1 81 71 152 T4 T7 Alexa Rippy Trevecca Nazarene U. +8 F +2 78 74 152 T4 6 Caroline Moore Lee University +8 F +3 77 75 152 7 T3 Annika Gino Lee University +9 F +5 76 77 153 8 T3 Megan Gaylor Milligan College +10 F +6 76 78 154 9 T10 Heidi Hinz Thomas University +13 F +5 80 77 157 T10 9 Kayla Chapman Truett McConnell +14 F +7 79 79 158 T10 T7 Haverly Harrold Lee University +14 F +8 78 80 158 12 T19 Ann Sullivan Milligan College +15 F +4 83 76 159 T13 T24 Raquel Romero Cumberland U. +17 F +5 84 77 161 T13 T19 Morgan Stuckey Cumberland U. +17 F +6 83 78 161 T15 T29 Kristen Sculley Thomas University +18 F +5 85 77 162 T15 T10 Caroline Parrish Thomas University +18 F +10 80 82 162 T15 T10 Sarah Son Milligan College +18 F +10 80 82 162 18 T33 Cassidy Gibson Milligan College +19 F +5 86 77 163 T19 T14 Rachael McMahan Trevecca Nazarene U.